Senegal

Senegal performs in the mid-range across all factors of the GSoDI framework except Participation, where it exhibits high performance and scores within the top 25 per cent of countries worldwide. Over the past five years, there have been declines in Access to Justice, Civil Liberties, Freedom of Expression, Freedom of the Press, Freedom of Association and Assembly, Personal Integrity and Security, reflecting recent weakening in the country’s democratic institutions during that time. Senegal is a lower-middle income country, with an economy that has traditionally revolved around agricultural products such as peanuts, sugarcane, and cotton. In recent decades, Senegal has seen the development of the industrial, mining, and services sectors.

Present-day Senegal was, for much of its precolonial history, an important part of several West African kingdoms and a critical node on trans-Saharan caravan routes. Starting in the 1600s, the area slowly came under the control of France, and Senegal re-gained its independence in 1960. While Senegal was initially a one-party state under President Léopold Senghor, the party system was gradually liberalized in the 1970s and 1980s, and the country experienced democratic transfers of power in 2000, 2012, and 2024. Electoral politics in Senegal are driven primarily by social inequities, not ethnicity. In particular, levels of education and the urban-rural divide are salient dividing lines. Patronage and clientelism have an impact on electoral competition. While Senegal is a unitary nation, a system of decentralization means that levels of development vary widely across the country. As a result, the primary issues in Senegalese politics are investing in development and combatting corruption.

Several aspects of social identity constitute additional cleavages in the West African nation, including religion. While Muslims account for a large majority of the population, Christians—mainly Catholics—comprise about five per cent of the total. Casamance, a southern region with a large Christian population, is culturally and geographically separated from the rest of Senegal by The Gambia, and has long fought a low-level conflict challenging the reach of the Senegalese state. An additional limitation on the state’s ability to project power is seen in the Islamic city of Touba, which enjoys a de facto autonomous status and provides its own social services. Issues of sexuality and gender are also salient in Senegal. LGBTQIA+ people regularly face societal protests and discrimination, and the country continues to criminalize consensual same-sex conduct. While Senegal is lauded for its leadership in women’s political participation and its constitution guarantees gender equality, women continue to face major challenges, including a strict abortion ban and widespread gender-based violence.

Opposition political movements faced significant challenges (including many legal proceedings) in the lead-up to the 2024 election, as public demand for democracy has remained high while satisfaction with institutional performance is low. The 2024 elections were held without incident after the Constitutional Court annulled their postponement, and the 2022 elections saw robust multiparty competition and no outright parliamentary majority, which are positive indicators for the future of democracy in the West African nation.

Looking ahead, Basic Welfare and Access to Justice are important areas to watch in light of the government’s new parliamentary majority and its ambitious reform agenda, which includes economic transformation and addressing rights violations perpetrated under the previous government. An ongoing regulatory crackdown on Senegal’s media outlets means that Freedom of the Press also bears monitoring.

Last updated: May 2025

https://www.idea.int/democracytracker/

October 2025

Signals cut and journalists arrested after media outlets interview government critic

The signal of 7TV and Radio Futurs Médias (RFM) were cut and two of their prominent journalists were arrested after conducting interviews with Madiambal Diagne, a journalist critical of the government, who is the subject of an international arrest warrant in connection with a corruption investigation, having fled to France in September. Maïmouna Ndour Faye, 7TV’s managing director, was arrested on 28 October shortly before a pre-recorded interview with Diagne was due to air, by gendarmes who also cut off the channel’s signal. She was reported to have been arrested for ‘undermining state security and the authority of the judiciary.’ A similar series of events unfolded the following day, with RFM’s editor-in-chief Babacar Fall arrested after conducting a live interview with Diagne. Both journalists were released without charge, but as of 31 October the signals for 7TV and RFM remained suspended on digital terrestrial television. Media investigations suggest that the suspensions did not comply with media regulations.

Sources: Jeune Afrique (1), Reporters Without Borders, Jeune Afrique (2)

August 2025

Senegal's anti-corruption reforms spark debate over presidential exemption

On 25 August, Senegal’s parliament approved anti-corruption reforms aimed at enhancing transparency and accountability. Key measures include restructuring the National Office for the Fight against Fraud and Corruption (OFNAC), to focus solely on corruption, with its reports submitted to the president and made public. The amendments also expand asset declaration requirements for senior civil servants to include a wider range of officials, lower the financial threshold for mandatory reporting, and mandate public disclosure of government audit reports. However, President Bassirou Diomaye Faye is exempt from these measures, a decision that has sparked sharp criticism from opposition leaders. They contend that presidential accountability is fundamental to fostering genuine transparency and protecting democracy. Critics warn that this exemption risks eroding public trust and raises serious concerns about the fair and consistent application of anti-corruption laws.

Sources: Jeune Afrique, APA News, Voice of Africa, Africa News

July 2025

Senegal launches investigation into 2021-2024 political violence

On 29 July, Senegal’s Justice Minister requested the country’s Public Prosecutor open an investigation into political violence between 2021 and 2024. During this period, at least 65 people are thought to have been killed and at least a thousand more injured in protests supporting then-opposition leader (now prime minister), Ousmane Sonko. While the previous administration passed a law purporting to grant a general amnesty for acts committed during these protests, the Constitutional Council ruled in April that the most serious violence, such as murder and torture, were not covered by the amnesty. The first summonses are expected in August, and the investigations are due to determine accountability for these types of violence and whether charges can be pursued against the perpetrators. Commentators warned, however, that the process may face significant legal and political challenges, including the loss or suppression of evidence.

Sources: Le Monde, Amnesty International, International IDEA, Deutsche Welle, Africa News

May 2025

Senegal indicts five former ministers for corruption

In May, Senegal’s High Court of Justice (Haute Cour de justice) indicted five former government ministers on charges of embezzlement and mismanagement of Covid-190 relief funds. The ministers served in the previous government of former President Macky Sall and are alleged to have misappropriated millions of dollars intended for pandemic relief and public welfare in what has become one of the biggest corruption scandals in Senegal’s political history. Their indictment followed a National Assembly (Assemblée Nationale) vote earlier in the month referring the ministers to the court, which has a special jurisdiction to prosecute senior government officials. Close associates of Macky Sall have alleged that the cases are politically motivated but the government has insisted on the independence of the judicial process.

Sources: Radio France Internationale, Jeune Afrique, New York University School of Law

See all event reports for this country

Global ranking per category of democratic performance in 2024

Basic Information

Human Rights Treaties

Performance by category over the last 6 months

Blogs

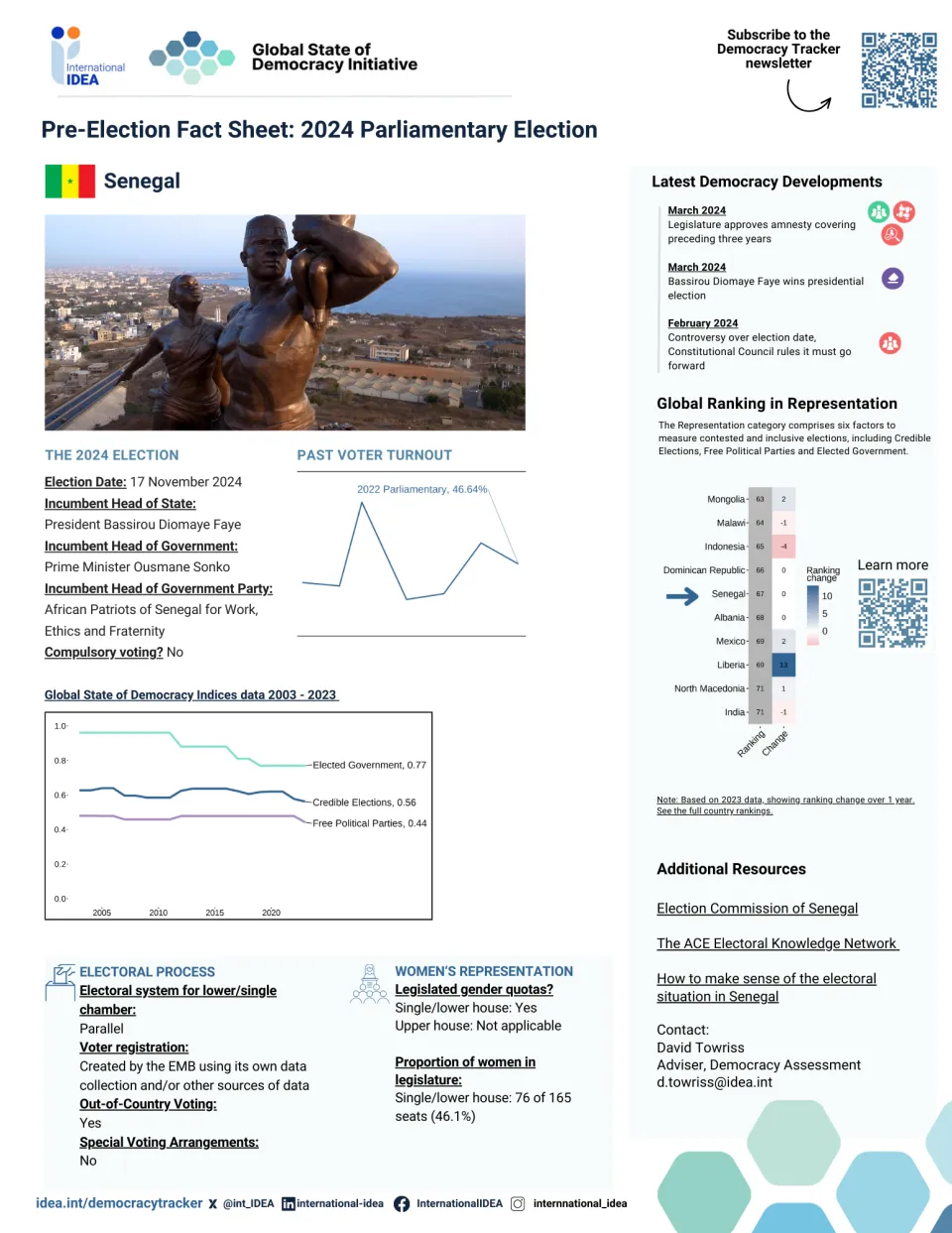

Election factsheets

Global State of Democracy Indices

Hover over the trend lines to see the exact data points across the years

Factors of Democratic Performance Over Time

Use the slider below to see how democratic performance has changed over time