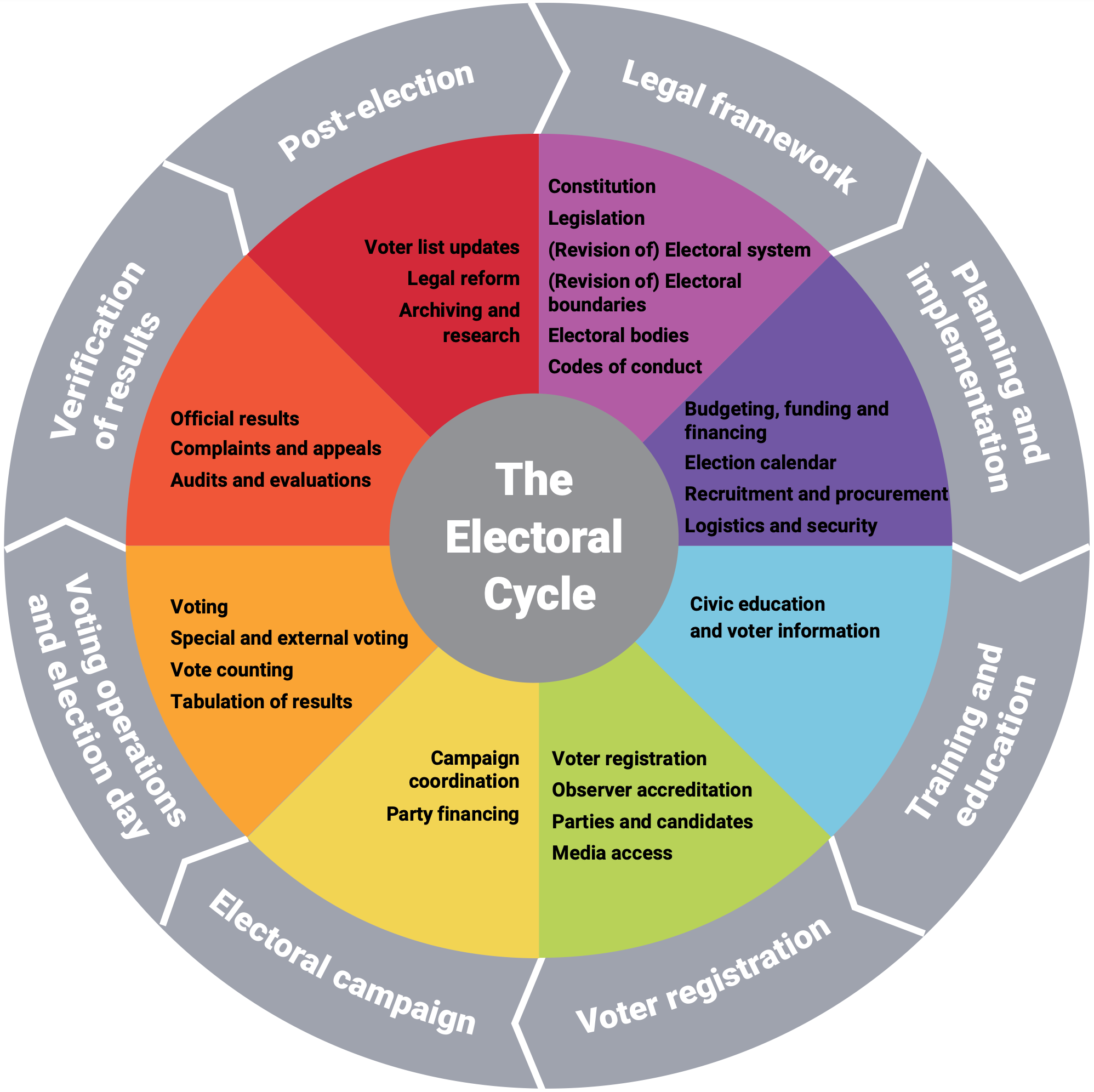

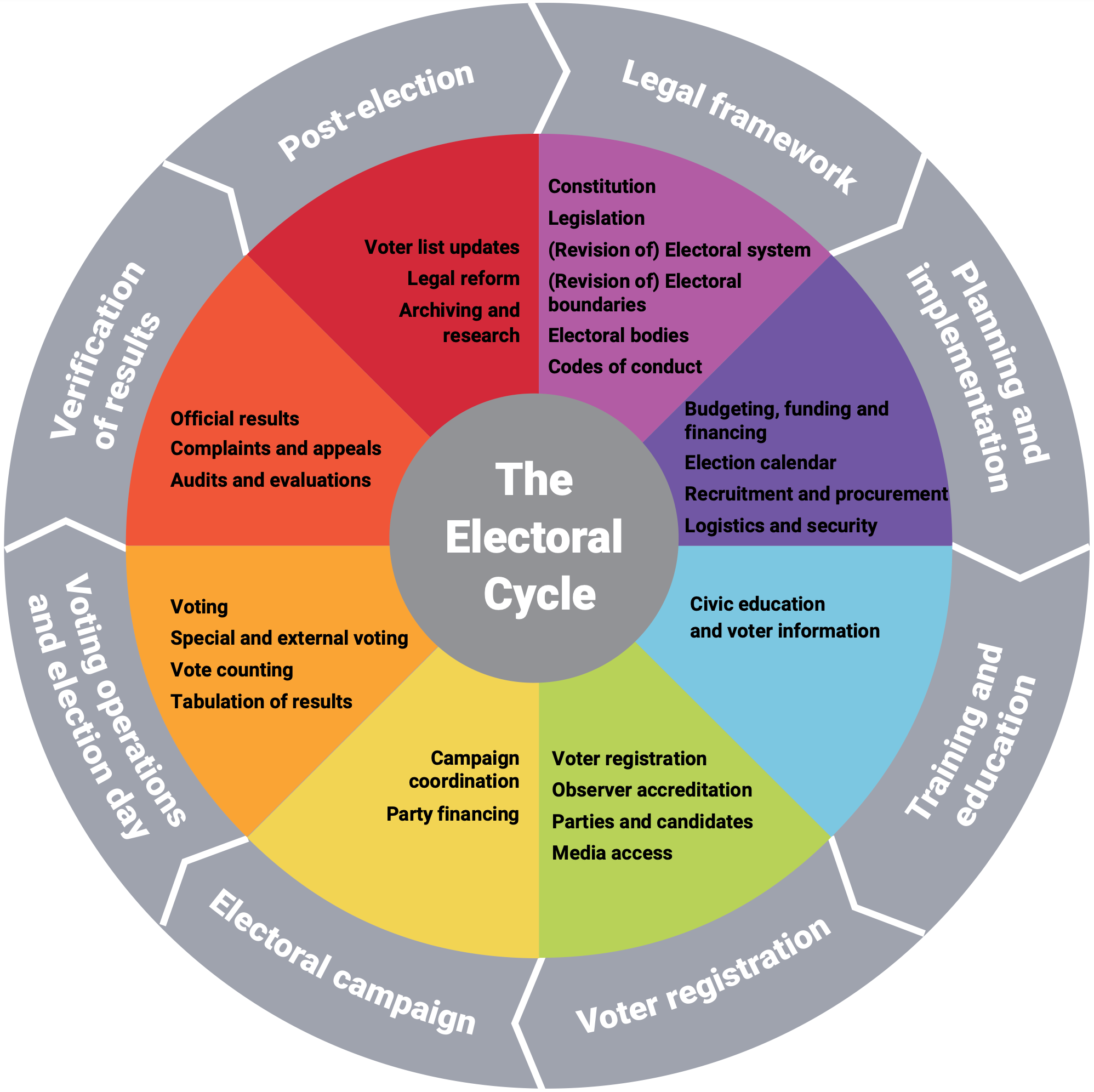

The data show that the public is likely to pay special attention to voting processes, as well as partisanship, EMB behaviour and aspects of the electoral system. Election-related legal challenges suggest that people are likely to be most focused on the voting process and vote counting, as these are two of the electoral operations with which voters and observers have the most familiarity and interaction (see Figure 7.1 for a comprehensive list of all the phases of the electoral cycle). Though experts cite long-standing concerns about the weakness of campaign finance and campaign-related media coverage, the public raises these issues less frequently. The relatively scant attention to these areas may be explained by the increased difficulty involved in finding relevant evidence, and by poor laws that do not sufficiently regulate the space for cases to be filed and by the somewhat indirect connection with the final vote tally.

The electoral cycle

View source

Catt, H., Ellis, A., Maley, M., Wall, A. and Wolf, P., Electoral Management Design, Revised Edition (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2014), <https://www.idea.int/publications/catalogue/electoral-management-design-revised-edition>, accessed 9 July 2024.

7.1. Disputed elections

Data show that disputed elections are fairly common. Almost one in five of these elections was challenged in court.

Between May 2020 and April 2024, at least 221 national elections were held across 159 countries. In line with the growing number of attacks on the credibility of elections, most visibly in Brazil and the USA, this data set shows that disputed elections are fairly common. Almost one in five of these elections (19.5 per cent) was challenged in court (see Figure 7.2).

In nearly all of these cases, the legal challenges were filed in contexts in which the GSoD Indices scores for Credible Elections were in the mid-range band of performance (0.4 to 0.7). The exceptions were in Czechia (2021) and Japan (2022), which were high-performing; and Burundi (2020), the Central African Republic (2020), Comoros (2023), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (2023), Egypt (2020) and Uganda (2021), which were low-performing. Cases were filed in every region of the world, though most were in Africa (see Figure 7.3). In fact, only 28.6 per cent of elections in Africa were not disputed in any way (see Annex B for a list of all disputed elections between May 2020 and April 2024, including contexts marked by boycotts, a public rejection of results and legal challenges).

Frequency of disputed elections (2020–2024)

View source

International IDEA, Disputed Elections Data set, <https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/disputed-elections>, accessed 20 August 2024.

Regional distribution of disputed elections (2020–2024)

View source

International IDEA, Disputed Elections Data set, <https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/disputed-elections>, accessed 20 August 2024.

This pattern corresponds to the mixed nature of mid-range-performing contexts, where there are clear strengths and weaknesses. In contexts marked by higher scores for Credible Elections, there may be less reason for challenges, while in contexts of lower credibility, there may be less incentive to file legal challenges at all, perhaps because of lower levels of trust in political institutions or because those institutions lack independence.

Figure 7.4 illustrates the range of values that is most common for elections where some form of contestation took place, with the majority of cases found in the range between 0.2 (low-performing) and 0.6 (mid-range-performing) for both Credible Elections and Judicial Independence.

Credible Elections and Judicial Independence scores for disputed and non-disputed elections (2020–2024)

View source

International IDEA, Disputed Elections Data set, <https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/disputed-elections>, accessed 20 August 2024; International IDEA, Global State of Democracy Indices, v7.1, 2023, <https://www.idea.int/democracytracker/gsod-indices>, accessed 15 March 2024.

Expert perceptions of the quality of elections also indicate that disputed elections are generally of lower quality than those that are not disputed. Figure 7.5 uses box plots to show the differences in the distributions of scores across the main (summative) PEI index and its 11 component indices (Garnett et al. 2023a). It is clear that the median value across every index is lower for the disputed elections, though the distribution is often more dispersed for the disputed elections. It is notable that the distribution of values for the non-disputed elections is particularly narrow, with a high median score for the Vote Count and Results indices. We see these two points of the electoral process to be key, a point we will return to in the discussion of court challenges below.

Expert perceptions of electoral integrity and disputed elections (2020–2022)

View source

Garnett, H. A., James, T. S., MacGregor, M. and Caal-Lam, S., ‘Perceptions of Electoral Integrity, (PEI-9.0)’, 2023, <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/2MFQ9K>; International IDEA, Disputed Elections Data set), accessed 20 August 2024.

We also might assume that elections are more likely to be disputed when there is more on the line. All elections matter, but presidential elections leave the winner with great power and the loser with nothing (in contrast with legislative elections, where losing parties are likely to at least have representation). Moreover, some presidential elections may matter more than others, as presidential power varies across countries, and the margin of victory will also vary across countries. In Figure 7.6, we plot the relationship between the vote share of the winning candidate and an executive power index developed by constitutional scholars (Elkins, Ginsburg and Melton 2012). It is indeed the case that, on average, disputed elections involve slightly higher levels of executive power. However, the difference is trivial (4.81 against 4.76). The average winner’s vote share in presidential elections was actually higher among the disputed elections than in the non-disputed elections (67.3 per cent versus 63.4 per cent). There have also been several disputed presidential elections where the winning candidate’s vote share was above 80 per cent, and others in which the level of executive power was quite low. So, the contestation of electoral outcomes is not determined by the stakes of the election or the margin of victory; instead, it is likely connected with real problems in the credibility of the election.

Overall, disputed elections tend to be in countries that are mid-range-performing in the factors of Judicial Independence and Credible Elections, and they also tend to be evaluated as more problematic by experts. While there is evidence that disputed elections are those where the levels of executive power are higher, the difference is slight enough that it is more likely that the elections are disputed because of real problems with credibility.

Disputes, vote shares and executive power across presidential elections (2020–2024)

View source

International Foundation for Electoral Systems, ElectionGuide, [n.d.], <https://www.electionguide.org>, accessed 9 July 2024; Comparative Constitutions Project, ‘Constitution Rankings’, 2016, <https://comparativeconstitutionsproject.org/ccp-rankings>, accessed 9 July 2024.

7.2. Types of disputes

This study catalogued three types of disputes: opposition boycotts, public statements indicating a rejection of results and legal challenges filed in court. Of course, boycotts, public rejections and legal challenges are not the only signs of disputed elections. Violence can also be a sign of disapproval or lack of trust in electoral processes (see Figure 7.7).

Overall, boycotts took place in 11.3 per cent of cases. Unsurprisingly, the majority of these contexts are categorized in the GSoD Indices as low-performing in Representation. A minority fell in the mid-range band of performance, but none were high-performing. In some contexts, boycotts took place in highly controlled environments, calling into question the degree to which boycott supporters could actually exercise their right not to participate. In the 2024 election in Belarus, for example, the context was so controlled that only parties that supported the ruling party’s policies were allowed to appear on the ballot. For the first time, observers from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe were not permitted to deploy an observation mission. In this environment, critics and analysts said mechanisms such as early voting were used to pressure people to participate (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty 2024). In other, more open, contexts, however, boycotts were more meaningful. In Tunisia, which is mid-range-performing in Representation, the 2023 opposition boycott of legislative elections contributed to the low turnout rate of 10.6 per cent (Amara and Mcdowall 2023).

Types of elections, and reactions of losing parties and candidates

View source

International IDEA, Disputed Elections Data set, <https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/disputed-elections>, accessed 20 August 2024.

In 19.5 per cent of the elections, a losing party or candidate (regardless of whether they represented a major or minor party) publicly rejected the results, and a legal challenge was filed in more than half of those cases (60.5 per cent). In one of the most extreme examples, former US President Donald Trump’s public rejection of the 2020 presidential election outcome resulted in the violent storming of the US Capitol (Sheerin 2022). In another relatively severe case, the leading opposition party rejected the results of Sierra Leone’s June 2023 general election. The rejection led to violence and mounting tension, as some opposition members refused to take their legislative seats. International mediation eventually led to a settlement, including an agreement to investigate the election (Africanews 2023). In 18 cases, legal challenges were filed without public rejections.

7.3. Grounds for legal challenges

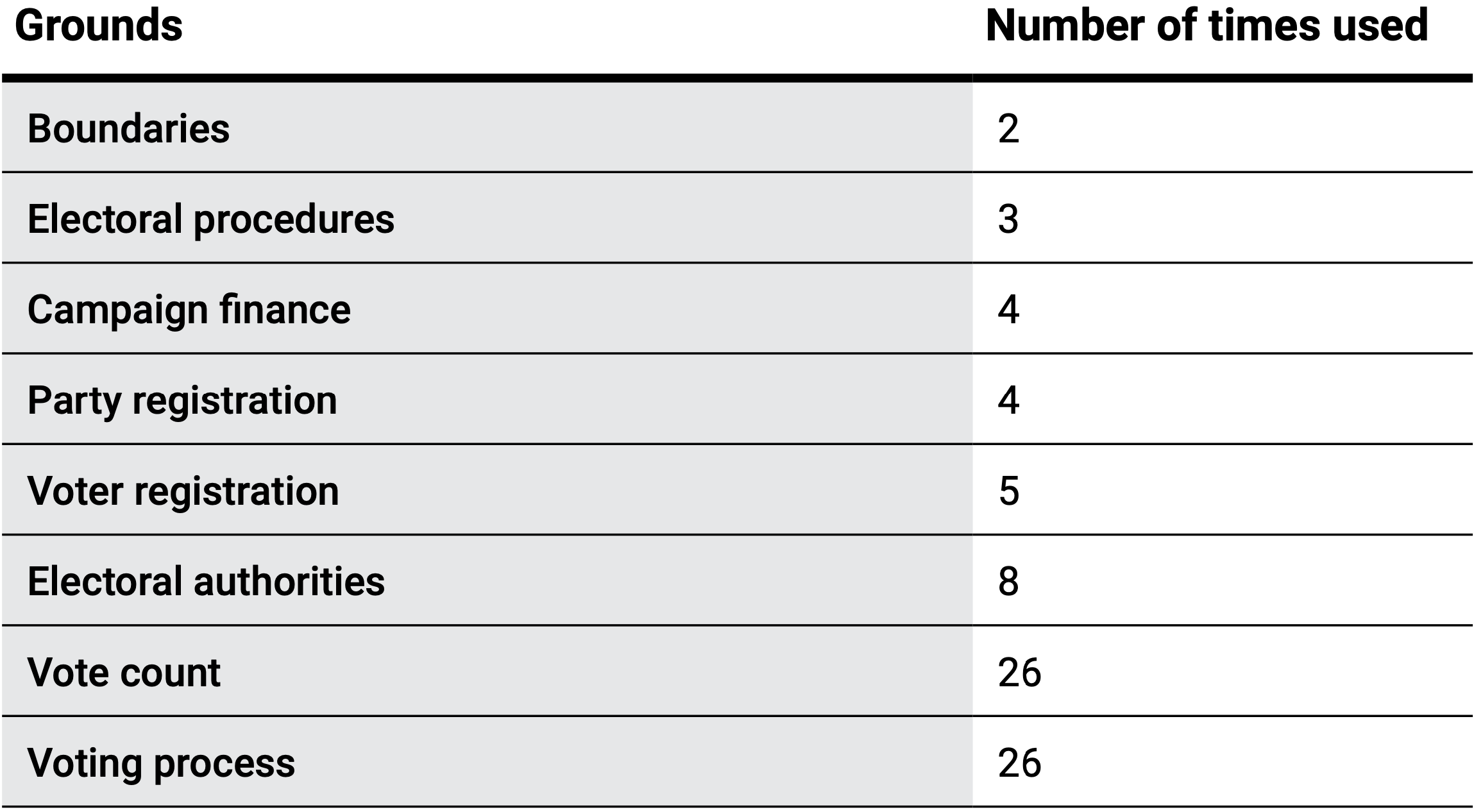

A close look at the 43 cases in which aggrieved parties filed court cases challenging the integrity of elections reveals several important points (see Table 7.1, which groups the challenges using the categories from the PEI questionnaire).

Grounds for legal challenges

View source

Authors’ calculations.

First, public attention is likely to be focused primarily on voting and the vote-counting process (as these are the areas of the electoral process invoked in court filings and likely to be the focus of media coverage). This focus stands in stark contrast to expert assessments that show confidence in this phase of the electoral cycle. There could be several reasons for this discrepancy. It could be that legal challenges focus on these aspects because they are the primary points at which voters have direct and personal interaction with the electoral cycle. Problems here will therefore have particular resonance with voters. It could also be that these problems are easier to document, understand and present to a court than others.

It is important to note that it may not always be clear which problems in a particular polling station or location are representative of more systematic issues or are serious enough to go beyond what is considered a negligible level of error in elections. Regardless, the prevalence of social media means that voters and the public can now express and disseminate their doubts widely. As a result, there may be cases in which issues or errors receive a disproportionate amount of unmerited attention (Rios Tobar 2024). The question of whether or not voters are right about the severity of a problem is less important, however, than the fact that issues that arise during voting and vote counting are those that may be most obvious to voters as they consider the credibility of their elections.

Second, expert concerns about campaign finance and campaign media do not appear to be priorities for the public. This finding is also likely a consequence of the fact that most voters do not have a great deal of personal experience with either of these phenomena and therefore do not personally feel the impact of the poor regulations behind them. While they may watch or hear campaign advertisements, for example, it may not be obvious that the political parties behind those ads do not receive equal and balanced coverage. Indeed, only parties and candidates (and not individuals) filed challenges alleging campaign finance violations. Even when violations are clear, it may be difficult to prove them, especially in cases where laws do not require transparent and public records. In some cases, the laws themselves may be insufficient or non-existent. Additionally, campaign finance violations and skewed campaign media are more difficult to link directly to problems with the final tally of votes, which is the part of the process that voters tend to focus on more.

References

Africanews, ‘Sierra Leone: President pledges to enforce agreement with opposition’, 25 October 2023, <https://www.africanews.com/2023/10/25/sierra-leone-president-pledges-to-enforce-agreement-with-opposition>, accessed 3 July 2024

Amara, T. and Mcdowall, l. A., ‘Tunisians elect weakened parliament on 11% turnout’, Reuters, 30 January 2023, <https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/polls-open-tunisian-election-with-turnout-under-scrutiny-2023-01-29>, accessed 3 July 2024

Elkins, Z., Ginsburg, T. and Melton, J., ‘Constitutional constraints on executive lawmaking’, 2012, <https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Constitutional-Constraints-on-Executive-Lawmaking-Elkins-Ginsburg/731557015933c97b062e6b1ce154b372c4658e39>, accessed 28 May 2024

Garnett, H. A., James, T. S., MacGregor, M. and Caal-Lam, S., Codebook—The Expert Survey of Perceptions of Electoral Integrity, Release 9.0 (PEI_9.0) (Electoral Integrity Project, 2023a), <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/2MFQ9K>

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, ‘Voting ends in Belarus elections called a “sham” by U.S. and “farce” by opposition’, 25 February 2024, <https://www.rferl.org/a/belarus-general-elections-opposition-boycott/32834340.html>, accessed 10 May 2024

Sheerin, J., ‘Capitol riots: “Wild” Trump tweet incited attack, says inquiry’, BBC News, 13 July 2022, <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-62140410>, accessed 14 July 2024