Trends now paint a picture of institutional stability across the Asia and the Pacific region. However, there has been no turnaround. Most countries in the region remain below the global average in every category other than Participation.

The broad democratic decline witnessed in the region in recent years has mostly come to a halt. However, factors of Civil Liberties, such as Freedom of Expression, and Freedom of Association and Assembly, largely continued their multi-year downward trend across the region.

After peaking in 2012, the region’s aggregate Freedom of the Press score has now reverted to 2001 levels. Significant declines have occurred in countries as varied as Australia, Kyrgyzstan, the Philippines, South Korea, Sri Lanka and Taiwan.

While the broad democratic decline has ended, there has not been a turnaround. Most countries in the region remain below the global average in every category other than Participation, although significant improvements in Rule of Law (Maldives, Taiwan and Uzbekistan) and Representation (Malaysia, Maldives and Thailand) are promising.

Across the region, ineffective parliaments and crackdowns on organized civil society have left the judiciary, anti-corruption commissions and at times mass street protests as the key countervailing institutions.

After several years of across-the-board declines, coinciding with the Covid-19 pandemic, both five-year and one-year trends now paint a picture of institutional stability across the Asia and the Pacific region. There are notable exceptions in Myanmar and Afghanistan, two states that have seen steep declines across all categories of measurement due to civil war and state collapse. Without those two states, however, the aggregate regional score in three of the four categories (Representation, Rights and Rule of Law) improved by a very small margin from 2021 to 2022.

These changes are small enough that no firm conclusions should be drawn about a potential democratic breakthrough or renewal, and several more years of data collection will be necessary before either continued stability, or possible future improvements, will be clearly observable.

It is also important not to confuse the possible temporary halt in democratic decline with an improvement: most countries in the region continue to score below the global average in Rule of Law, Rights and Representation.

The relative stability can be seen in Figure 5.1, in which states are coded according to the net total of advancing or declining factor scores between 2017 and 2022 (the number of factors with a negative five-year change subtracted from the number of factors with a positive change over the same time period). Most states in the region—23 out of 35—saw a net advance or decline of, at most, only one factor.

There has been overall stability in democratic performance across Asia and the Pacific between 2017 and 2022

International IDEA, The Global State of Democracy Indices v7.1, 2023.

Historically high-performing countries like Australia, Japan and South Korea still perform at similar levels across the GSoD Indices. Entrenched authoritarian regimes in Laos (146 in Rights and Representation) and China (134 and 157 in the same categories, respectively) continue to be free of any indications of significant change, despite the outbreak of protests on a historic scale across the latter in late 2022 (HRW 2023). Asia’s democracies—and would-be aspiring democratizers in the region’s more authoritarian states—still face exogenous and endogenous challenges, both towards revitalizing institutions and in preventing further democratic decline.

Malaysia and Maldives made significant advances in Representation in the last five years; the former as a result of improvements in Credible Elections and Free Political Parties, and the latter Effective Parliament, Credible Elections, Elected Government and Free Political Parties. Malaysia (ranked at 92) rose 17 places in the rankings for Representation on 2021, and Maldives (83) three places. Afghanistan, Cambodia, India and the Philippines saw significant declines in Credible Elections scores over five years, while Malaysia, Maldives, Sri Lanka and Thailand saw advances over the same time span.

Malaysia’s improvement can be credited in part to the convincing defeat of the long-powerful United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) in November 2022 elections, which had clung to power in the face of persistent and wide-ranging corruption allegations (BERSIH 2022; Lee 2022; Wee 2022).

India, which the UN estimates overtook China as the world’s most populous country in April 2023, continues to perform at the mid-range level in Representation, despite a statistically significant five-year decline, as well as similar declines in Credible Elections and Free Political Parties (UN DESA 2023). Concerns were raised about how the ruling party benefited from unequal treatment by Facebook and used hate speech in the 2019 election (Purnell and Horwitz 2020; Safi 2019; Tiwary 2022; Chakrabarty 2023).

The Election Commission of India has sought to regulate and proscribe hate speech, despite lacking the specific statutory authority to do so; instead, it used provisions of the Indian Penal Code and the Representation of People Act (The Scroll 2022). The Supreme Court of India has also repeatedly intervened, including via an April 2023 order mandating all states and union territories to register occurrences of hate speech without waiting for a formal complaint to be filed (Rajagopal 2023). In August 2023, critics and opposition parties argued that proposed changes to the process of nominating members of the Election Commission risked curtailing its independence (Jain 2023; The Wire 2023).

In 2023, questions about the equal treatment of political parties continued, especially around alleged bias in a legal case that has seen the conviction of Rahul Gandhi, senior leader of the Indian National Congress, the main opposition party. Gandhi was sentenced to two years in prison for defamation in March 2023, which could have barred his participation in the 2024 elections. However, the Supreme Court stayed the conviction in August 2023 (Landrin 2023; Mathur 2023; Venkatesan 2023).

Bangladesh saw a significant decline in Elected Government stemming from the lack of improvement since the much-criticized 2018 general elections (The Wire 2018; Siddiqui and Paul 2019; HRW 2018). The next general elections are scheduled to be held in 2024, and tensions, fatal protests and arrests of leading opposition figures began as early as 2022 (see also the case study on Bangladesh) (Hasnat and Mashal 2022).

Political instability in Nepal is reflected in a five-year decline in Effective Parliament. The parliament had been dissolved by the prime minister in 2021, but political deadlock continued after it was reinstated by a court order (Bhattarai 2021). Political coalitions have continued to be unstable since the November 2022 elections, and the government underwent seven cabinet reshuffles within its first four months in power, with analysts indicating that the primary political opposition appeared more interested in replacing the governing coalition partners than providing parliamentary oversight (ANI News 2023; Healy and Moktan 2023).

A continuing area of worry is Civil Liberties, where India, Maldives, the Philippines and Sri Lanka saw significant declines over five years, as did already low-performing Afghanistan and China. In the global rankings for Rights, India (ranked at 104) dropped 3 places, Maldives (98) 5 places and Sri Lanka (88) 18 places since 2021. By virtue of other countries across the world facing larger declines, the Philippines (90) improved its position in the rankings by one.

The most significant outliers, in terms of the overall pause in democratic decline, were seen in the factors Freedom of Expression, Freedom of the Press, and Freedom of Association and Assembly, which largely continued their downward trend of previous years. Asia and the Pacific’s regional average for Civil Liberties is well below the world’s, and most people in the region live in a country that has seen a significant five-year decline in its Civil Liberties score.

In mid-performing India, declines in Freedom of Expression and Freedom of Association and Assembly were exemplified by Amnesty International closing its doors there in 2020, citing raids on its offices and its trustees’ residences and the eventual freezing of its accounts (Amnesty International n.d.).

In also mid-performing Sri Lanka, the state responded to hundreds of days of mass protests—which forced the president to resign—with the introduction of laws that restrict people’s freedom of association and assembly and a constitutional amendment that has been criticized for retaining the very concentration of power in the executive that it seemingly seeks to contain (HRW 2022b). Sri Lanka’s Centre for Policy Alternatives described it as ‘a failure to understand the underlying public frustration in the system of governance that culminated in mass scale protests across Sri Lanka’ (CPA 2022).

The declines in Freedom of the Press and Freedom of Expression (Figure 5.2) found in the GSoD Indices have taken place during rapid changes in the way media is consumed and shared. Since 2017, Internet penetration in Asia and the Pacific has risen from 48 to 64 per cent, albeit unequally distributed and reflecting pre-existing social inequalities (ITU 2017, 2022; Setiawan, Pape and Beschorner 2022).

The hope in some quarters that digitalization and a levelling of media systems would drive democratic change proved to be misplaced, as newer forms of online and social media became a site of political contestation rather than a technical correction to government censorship and private US and Chinese platform monopolies (Sinpeng 2020; Farrell 2022).

Instead, traditional and social media constitute a constantly changing ‘smooth space’ that regulators, political parties and journalists must negotiate in order to protect the core democratic CI elections (Hubert 2019; Tan 2020).

Variations in Freedom of Expression and Freedom of the Press for selected countries 2017–2022

International IDEA, The Global State of Democracy Indices v7.1, 2023.

Gender Equality showed limited changes across the region, with only two significant declines—in Afghanistan and Kyrgyzstan—over the last five years. Australia, New Zealand and Taiwan remain the highest-performing countries in this factor in the region, with the vast majority of other countries performing at the mid-range.

Afghanistan, Fiji, Kyrgyzstan, Myanmar and Taiwan have all experienced statistically significant declines in Social Group Equality over the last five years. Despite a long journey ahead, recent advances for LGBTQIA+ rights in the courts in Japan, Sri Lanka, Taiwan and elsewhere related to same-sex marriage rights, and decriminalizing homosexuality could potentially signal an opening for long-awaited reforms (International IDEA 2023a).

Rule of Law scores vary widely across Asia and the Pacific, with Oceania and East Asia the highest-performing subregions and Central Asia the lowest. This category is also where the most dramatic changes have taken place over the last five years, as the modest reforms in Uzbekistan (ranked at 114) and the democratic contraction in Kyrgyzstan (117) have led the former to surpass the latter.

Weak parliaments and attacks on media have resulted in more technocratic institutions, such as anti-corruption bureaus and the judiciary, to push back against executive overreach in the region.

In East and South Asia, top courts have delivered landmark rulings expanding rights for women and LGBTQIA+ persons in the absence of parliamentary or governmental action, ranging from removing the requirement of full-sex reassignment surgery for those seeking legal gender recognition in Hong Kong (Lau 2023), to recognizing the social benefits of same-sex couples in South Korea (Yoon 2023) and legalizing abortion regardless of marital status in India (Pandey 2022).

High courts can play a crucial role in protecting free speech. In Pakistan, a colonial-era sedition law criminalizing criticism of the government was struck down in March 2023 (Al Jazeera 2023), and in the Philippines, a tax court cleared Nobel laureate Maria Ressa of four tax evasion charges widely held to be politically motivated. It was hailed as a win for press freedom and the rule of law (OHCHR 2023a).

With the exception of Central Asia, countries in the region typically score at mid-range or high-performing levels of Participation. The major changes are in Fiji (ranked at 50) and Maldives (93), which have seen significant improvements in Civil Society in the last five years. Taiwan (4) moved up three places in Participation over the past year and remains the highest-ranked country in the region.

Mass public participation in electoral cycles remains the most powerful countervailing force as underlined by the 2022 Malaysian and 2023 Thai elections.

After lowering the voting age from 21 to 18 years and introducing automatic voter registration, the 2022 Malaysian election saw an increased turnout of three million more voters, compared with the previous election cycle in 2018 (Fernandez Gibaja 2022; International IDEA n.d.). In this case the actions of the electorate in largely removing a corruption-troubled party from power worked in complement with the nation’s anti-corruption commission, a fourth-branch institution that had successfully obtained the conviction of former prime minister and UMNO president Najib Razak for corruption, for his role in the 1MDB scandal (Latiff 2023).

Thailand also saw the highest voter turnout in its history (albeit by a small margin) in May 2023 parliamentary elections and a historic win for the Move Forward Party at the expense of both the ruling conservative coalition and traditional opposition Pheu Thai Party (International IDEA 2023b). Although roundly interpreted as a rejection of the continued rule of Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha, who took power in a 2014 coup, Move Forward’s path to gaining power was blocked by the military-appointed Senate. By August 2023, Move Forward leader Pita Limjaroenrat’s leadership bid had failed in the face of Senate opposition, and Pheu Thai was negotiating with political parties allied with the military, in order to build a ruling coalition (Nikkei Asia 2023).

Thailand (118) has witnessed a surge in civic participation, slowly improving its ranking in Participation over the past few years, rising three places between 2021 and 2022. Youth engagement, activism and civic engagement have only intensified since the 2014 coup d’état, with anti-government protests in 2020.

Elsewhere in the region, the December 2022 Fiji election saw the peaceful removal of a long-time prime minister who had also taken power in a coup (see also the case study on Fiji). Uzbekistan (148), similarly to Thailand, has moved up six places in Participation over the past year, partly attributed to the easing of restrictive CSO registration procedures.

While slight openings for civic engagement in both Thailand and Uzbekistan demonstrate much-needed resilience in the face of repressive environments, the continued crackdown on protests and existing legal restrictions on CSOs indicates that more needs to be done to sustain democratic change (Solod 2022; CIVICUS 2022a).

Low- and middle-income nations in South East Asia and the Pacific are arguably subject to the most external pressure in the region. Despite the efforts of governments to focus international diplomatic relations on questions of development aid and assistance, they increasingly operate in a world interpreted by great powers through the lens of zero-sum and militarized competition (Kaiku 2023; Xiao 2022; Thu 2023; Needham 2022).

Australia, China and the USA are increasingly interested in strengthening and building ties with security forces in a region where military coups are often within living memory (Baldor 2023).

The lingering economic cost of the pandemic continues to put pressure on Asia and the Pacific’s low- and middle-income countries, as the region is likely to experience the most significant long-term economic shock from the Covid-19 pandemic (Kothari and Tawk 2023).[5] These countries are also under continuing pressure from rising European and US interest rates that constrain and limit public policymaking (Arteta, Kamin and Ruch 2023; Iacoviello and Navarro 2018).

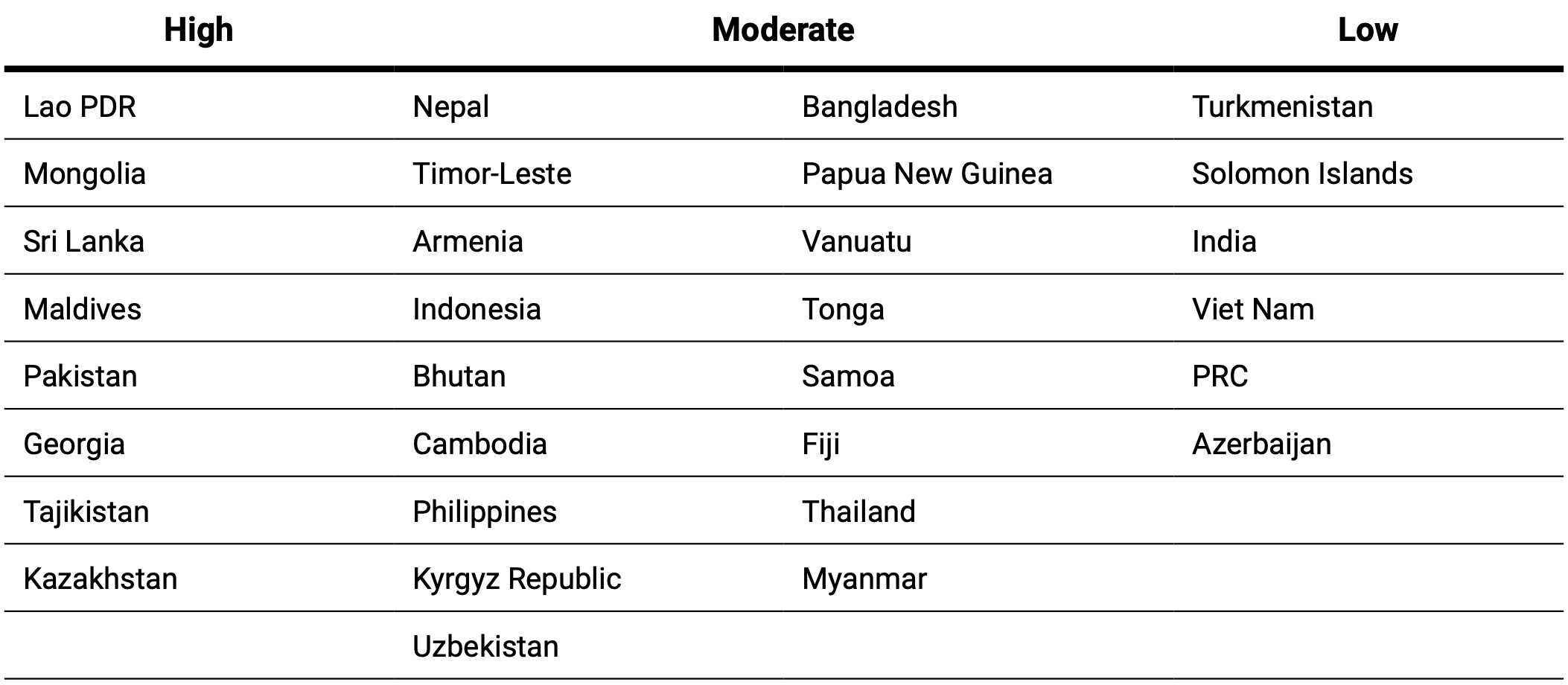

According to an April 2023 Asian Development Bank report, 23 countries covered by the GSoD Indices in the region are at high or moderate risk of being unable to manage their external debt in the near future (Table 5.1). A country overburdened with debt also imposes costs on its trading partners, as funds that could have been used to import goods or invest in productive enterprises are instead set aside for debt service. This means that, while creditor nations’ financial sectors benefit in the short term, their real economies suffer and the potential for systemic risk only grows (Pettis 2023).

Threats to freedom of speech extend beyond chaotic online spaces of proliferating home-grown and foreign disinformation, or social media platform-facilitated intercommunal violence (Brandt et al. 2022; Purnell and Horwitz 2021). In 2022 and 2023, Bangladesh, Cambodia and Kyrgyzstan instituted outright bans on popular independent and opposition media outlets, and a Pakistani court strengthened the country’s blasphemy laws (Imanaliyeva 2023; Masood 2023; OHCHR 2023b; Daily Star 2023). The South Korean government was criticized domestically and internationally for barring a major media outlet from a travelling press pool and for cutting public broadcasting funding amid claims of political bias in its programming as it was seen as having an unfavourable disposition towards the Yoon Suk Yeol administration (CIVICUS 2022b; RSF 2022).

The slow decline in Freedom of the Press is a long-term trend, having regressed to 2001 levels since the regional average’s historical peak in 2012 (Figure 5.3).

External debt vulnerabilities (from Asian Development Bank)

Notes: Lao PDR = Lao People’s Democratic Republic; PRC = People’s Republic of China; PNG = private nonguaranteed; PPG = public and publicly guaranteed.

External debt includes both public (PPG) and private (PNG) debt. Economies are ranked based on their average scores derived from rating of 1 = high, 0.5 = moderate, 0 = low on indicators of external debt used in Table 5.1. They are listed in order of scores from high to low per group (top to bottom, left to right). Economies with available data on liquidity indicators are excluded from the ranking.

Please note that some countries in the table are not listed in the region Asia and the Pacific in International IDEA’s GSoD Indices.

Table is redrawn from ‘Table 3: External Debt Vulnerabilities 2022-2023—Ranking Overall’, in Ferrarini, B., Dagli, S. and Mariano, P., Sovereign Debt Vulnerabilities in Asia and the Pacific, ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 680 (Manilla: Asian Development Bank, 2023), <https://doi.org/10.22617/WPS230124-2>

If reversals of previous years’ democratic trends are to involve delivering on the social and economic goods that underlie democratic social contracts, many countries in the region face a continuing uphill battle (Stubbs et al. 2023). Debt crises can act as an obstruction to the core CI of regularly scheduled elections, as has been the case in Pakistan and Sri Lanka (see below).

Contrary to the developing status quo of ‘a more narrow and exclusive focus on maximizing the wealth and power of their state’ in international relations, countries in Asia and the Pacific would be better served by strengthening regional cooperation (Helleiner 2023). Regional networks, such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF), could theoretically act as a stabilizing and democratizing counterweight in a world of enhanced great-power competition—although no such regional coalition has yet risen to the challenge (Damuri 2023); HRW 2022a).

Diverging member state priorities and internal tensions have revealed fractures within regional bodies such as ASEAN and PIF, which has hampered their ability to move from talk to action on pressing issues, such as Myanmar and presenting a unified front on climate change, respectively (Lawson 2022; Council on Foreign Relations 2022).

International economic fetters played a significant role in the 2023 political crisis in Pakistan, whose years of living on the verge of default amplified its vulnerability and hampered its response to 2022’s climate change-fuelled floods (Yap 2023; Runey 2023). The parliament that oversaw the removal of Imran Khan from the premiership in April 2022 proved no better at managing the country’s extremely distressed finances, and the ensuing political crisis spiralled out of all actors’ control by mid-2023 (Burney 2023; Joles 2023).

Freedom of the Press improved from 2001 to 2012, but had returned to 2001 levels in 2022 (each dot represents a country)

International IDEA, The Global State of Democracy Indices v7.1, 2023.

While these state and private limitations on freedom of expression and the media remain effective, the ability of the press or mass political action to play the role of a CI is likely to be limited. In less democratic regimes, mass media institutions are known to publish corruption investigations that result in the removal of high-ranking officials, but only with the government’s implicit or explicit permission. The top-down liberalizations and purported democratizations in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have included the arrests and prosecution of high-ranking officials on what appear to be genuine cases of corruption and abuse of office, but only when it enhances the stability of those autocratic regimes (RFE/RL’s Uzbek Service 2023; BBC News 2022).

Despite the prevalence of defamation and cybercrime laws used to silence dissent, civic engagement can become a powerful countervailing force in consolidating more inclusive democracies. Collective action has the power to deliver a strong mandate for change, even in repressive circumstances, as in Thailand, where MFP, a progressive party promising monarchy and military reforms, won the most votes in an election that saw a record voter turnout. Election observers noted that the increased participation of civil society and the media led to a more transparent election than in 2019 (ANFREL 2023). Indeed, Thailand’s Civic Engagement score is slightly below the global average and is among the strongest performing in Asia and the Pacific; noteworthy in that it has only increased since the 2014 coup d’état, reflecting the democratic energy that fuelled the 2020–2021 mass demonstrations and calls for monarchy reform. Since 2020, social media has also played a pivotal role in spurring online civic engagement—also believed to have contributed to MFP’s victory (Leesa-Nguansuk 2023).

Advances and declines in Absence of Corruption in selected countries 2017–2022

International IDEA, The Global State of Democracy Indices v7.1, 2023.

National anti-corruption commissions have proven to be a vital CI for holding political elites accountable.

Australia, whose Absence of Corruption score has not yet recovered from a significant decline in 2013, took the positive step in November 2022 of establishing a federal anti-corruption commission to boost whistleblower protections and investigate public officials for corruption (The Australia Institute n.d.).

The Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission, established in 2009, has solved several high-profile corruption cases over the years and secured the indictment of two former prime ministers in 2022 and 2023 (Strangio 2023; Zhu 2022). Malaysia has seen a corresponding statistically significant increase in Absence of Corruption in the last five years (Figure 5.4).

The work of the Indonesian Corruption Eradication Commission (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi; KPK) led to the ‘conviction of hundreds of individuals, including the former head of the Constitutional Court, the senior deputy governor of the country’s central bank, leaders of political parties, government ministers, chairs of regulatory agencies and oversight bodies, as well as subnational executive government heads including governors and mayors’ between 2005 and 2019 (Buehler 2019). The KPK’s key successes were made possible due to the support it received from other CIs, including CSOs and a mostly free press (Umam et al. 2020). The KPK’s years of success eventually provoked an elite backlash. Legislation from 2019 substantially weakened the agency and removed much of its independence, and it is unclear when or if it will recover its former efficacy (Mulholland and Sanit 2020).

As with other CIs, efficacy is conditional on a number of factors. Anti-corruption commissions can only be effective CIs when they are backed by political will, an adequate budget, and most importantly, when they are truly independent of the executive (Quah 2017). A co-opted or constrained anti-corruption commission is likely to fall prey to being used as a political leader’s ‘attack dog’, or a ‘paper tiger’ used to head off demands for real anti-corruption reform (Quah 2021; Siddiquee and Zafarullah 2020).

As the rise and fall of Indonesia’s KPK shows, anti-corruption commissions can be part of a well-functioning and complementary set of democratic CIs, such as well-run and open elections and a free and independent media. They are not a replacement for other CIs or a shortcut to sustainable democratization—both Hong Kong and Singapore established rigorous anti-corruption commissions that were never intended to push their countries towards a more democratic path (Meagher 2005).

Distribution of Rule of Law scores by subregion 2022 (median scores for subregions annotated)

International IDEA, The Global State of Democracy Indices v7.1, 2023.

Across the region, the judiciaries have been core defenders of the rule of law and the expansion of civil liberties, but Rule of Law scores show great variation both within and between subregions (Figure 5.5).

The Supreme Courts of Sri Lanka and Pakistan have similarly been called on to uphold the right to vote in response to executive decisions seeking to postpone local elections in 2023 (Perera 2023; Aamir 2023). Yet, in defiance of the court orders, elections in both cases remain delayed, signalling growing points of contention between the judiciary and the executive, as democracy is held hostage to funding and politics.

Reliance on the judiciary as a CI is not without drawbacks. A too-strong judiciary may unintentionally undermine or destabilize the executive or parliament (Husain 2018). The overreliance on the Pakistani judiciary for democratic progress may have paved the way for Pakistan’s 2023 constitutional crisis by weakening parliament in relation to the military. Dependence on one particular CI can result in a concentration of non-democratic power elsewhere, such as permitting the military to assume more direct power by arguing that it is the only institution capable of providing governance (Ayoob 2022). The top-heavy Pakistani judiciary is also a case study in the ‘judicialization’ of politics, where the resort to judicial decree weakens reliance on elections, the core of any democratic polity (Husain 2018).

Conversely, non-independent and politicized judicial institutions can also be weaponized to restrict fundamental freedoms. In Cambodia and Bangladesh (see also the case study on Bangladesh), crackdowns on opposition groups in the last year have been facilitated by judicial harassment.

While some Asian and Pacific countries have made progress in the Rule of Law and Representation categories, most nations in the region still lag behind the global average. Restrictions on freedom of speech and media censorship remain areas of concern, and external debt and economic constraints further hinder democratic progress. The judiciary and anti-corruption commissions have emerged as key CIs in safeguarding democratic values, although their efficacy rests on factors such as political will and independence. Broadening civic engagement has renewed demands for democratic change, as seen in Thailand’s recent election. Collective efforts will be needed to revitalize key institutions, such as parliaments, to prevent further democratic declines.

ANI News, ‘Nepal cabinet reshuffled for seventh time, 5 ministries still remain with PM Dahal’, 31 March 2023, <https://www.aninews.in/news/world/asia/nepal-cabinet-reshuffled-for-seventh-time-5-ministries-still-remain-with-pm-dahal20230331224746>, accessed 30 June 2023

Aamir, A., ‘Pakistan faces constitutional crisis over elections: What to know’, Nikkei Asia, 2023, <https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Pakistan-faces-constitutional-crisis-over-elections-What-to-know>, accessed 25 May 2023

Al Jazeera, ‘Pakistani court strikes down sedition law in win for free speech’, 30 March 2023, <https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/3/30/pakistani-court-strikes-down-sedition-law-in-win-for-free-speech>, accessed 11 May 2023

Amnesty International, ‘Protect our human rights work in India’, [n.d.], <https://www.amnesty.org/en/petition/protect-our-human-rights-work-in-india>, accessed 22 August 2023

Arteta, C., Kamin, S. B. and Ruch, F. U., ‘How do rising U.S. interest rates affect emerging and developing economies?’, The World Bank, 7 February 2023, <https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/how-do-rising-us-interest-rates-affect-emerging-and-developing-economies>, accessed 11 May 2023

Asian Network for Free Elections (ANFREL), ‘ANFREL IEOM to the 2023 Thai General Election: Interim Report’, 17 May 2023, <https://anfrel.org/anfrel-ieom-to-the-2023-thai-general-election-interim-report>, accessed 24 May 2023

The Australia Institute, ‘The National Anti-Corruption Commission’, [n.d.], <https://australiainstitute.org.au/initiative/a-national-integrity-commission-with-teeth/the-national-anti-corruption-commission>, accessed 11 May 2023 Ayoob, M., ‘Pakistan’s constitutional crisis could lead to military rule’, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, The Strategist blog, 4 April 2022, �https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/pakistans-constitutional-crisis-could-lead-to-military-rule�, accessed 11 May 2023

The Australia Institute, ‘The National Anti-Corruption Commission’, [n.d.], <https://australiainstitute.org.au/initiative/a-national-integrity-commission-with-teeth/the-national-anti-corruption-commission>, accessed 11 May 2023 Ayoob, M., ‘Pakistan’s constitutional crisis could lead to military rule’, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, The Strategist blog, 4 April 2022, �https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/pakistans-constitutional-crisis-could-lead-to-military-rule�, accessed 11 May 2023

BBC News, ‘Kazakhstan unrest: Ex-intelligence chief arrested for treason’, 8 January 2022, <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-59922258>, accessed 11 May 2023

Baldor, L. C., ‘How the US is boosting military alliances to counter China’, Associated Press, 2 February 2023, <https://apnews.com/article/politics-antony-blinken-beijing-north-korea-china-9f9432c118f297fc27a9be01c460316e>, accessed 11 May 2023

Bhattarai, K. D., ‘Why Nepal’s current political deadlock is unlikely to end anytime soon’, The Wire, 15 March 2021, <https://thewire.in/south-asia/nepal-supreme-court-parliament-kp-oli-political-deadlock>, accessed 30 June 2023

Brandt, J., Ichihara, M., Jalli, N., Shen, P. and Sinpeng, A., ‘Impact of disinformation on democracy in Asia’, Brookings Institution, 14 December 2022, <https://www.brookings.edu/research/impact-of-disinformation-on-democracy-in-asia>, accessed 11 May 2023

Buehler, M., ‘Indonesia takes a wrong turn in crusade against corruption’, Financial Times, 2 October 2019, <https://www.ft.com/content/048ecc9c-7819-3553-9ec7-546dd19f09ae>, accessed 11 May 2023

Burney, U., ‘Imran Khan arrested from IHC; court deems ex-PM’s arrest legal’, DAWN, 9 May 2023, <https://www.dawn.com/news/1751782>, accessed 11 May 2023

CIVICUS, ‘Despite UN review, Thai Government continues to silence dissent, push restrictive NGO bill’, CIVICUS Monitor, 4 April 2022a, <https://monitor.civicus.org/explore/despite-un-review-thai-government-continues-silence-dissent-push-restrictive-ngo-bill>, accessed 30 June 2023

Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA), ‘CPA statement on the government’s revised twenty second amendment to the Constitution Bill’, press Release, 18 August 2022, <https://www.cpalanka.org/cpa-statement-on-the-governments-revised-twenty-second-amendment-to-the-constitution-bill>, accessed 15 September 2022

Chakrabarty, S., ‘Bill introduced to remove CJI from panel to select Election Commissioners’, The Hindu, 10 August 2023, <https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/bill-moved-to-remove-cji-from-panel-to-select-election-commissioners/article67180873.ece>, accessed 22 August 2023

Coalition for Clean and Fair Elections (BERSIH), ‘Preliminary report of the 15th general election’, 6 December 2022, <https://bersih.org/2022/12/06/preliminary-report-of-the-15th-general-election>, accessed 30 June 2023

Daily Star, ‘Dainik Dinkal stops publication’, 21 February 2023, <https://www.thedailystar.net/news/bangladesh/news/dainik-dinkal-stops-publication-3253461>, accessed 11 May 2023

Damuri, Y. R., ‘An agenda for regional economic and security cooperation’, East Asia Forum, 12 January 2023, <https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2023/01/12/an-agenda-for-regional-economic-and-security-cooperation>, accessed 11 May 2023

Farrell, M., ‘Your platform is not an ecosystem’, Crooked Timber, 8 December 2022, <https://crookedtimber.org/2022/12/08/your-platform-is-not-an-ecosystem>, accessed 11 May 2023

Fernandez Gibaja, A., ‘How young voters are revamping democracy in Malaysia’, Democracy Notes [International IDEA blog], 17 November 2022, <https://www.idea.int/blog/how-young-voters-are-revamping-democracy-malaysia>, accessed 7 July 2023

Hasnat, S. and Mashal, M., ‘Bangladesh arrests opposition leaders as crackdown intensifies’, New York Times, 9 December 2022, <https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/09/world/asia/bangladesh-protests-election.html>, accessed 30 June 2023

Healy, D. and Moktan, S., ‘In Nepal, post-election politicking takes precedence over governance’, United States Institute of Peace, 8 February 2023, <https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/02/nepal-post-election-politicking-takes-precedence-over-governance>, accessed 30 June 2023

Helleiner, E., ‘The revival of neomercantilism’, Phenomenal World, 27 April 2023, <https://www.phenomenalworld.org/analysis/neomercantilism>, accessed 11 May 2023

Huang, K. and Han, M., ‘Did China’s street protests end harsh Covid policies?’, Council on Foreign Relations, 14 December 2022, <https://www.cfr.org/blog/did-chinas-street-protests-end-harsh-covid-policies>, accessed 9 July 2023

Hubert, C., ‘Smooth/straited’, Christian Hubert Studio, 13 August 2019, <https://www.christianhubert.com/writing/smoothstriated>, accessed 7 July 2023

Human Rights Watch (HRW), ‘Creating Panic: Bangladesh election crackdown on political opponents and critics’, 22 December 2018, <https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/12/22/creating-panic/bangladesh-election-crackdown-political-opponents-and-critics>, accessed 30 June 2023

Husain, W., The Judicialization of Politics in Pakistan: A Comparative Study of Judicial Restraint and its Development in India, the US and Pakistan (London: Routledge, 2018), <https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351190114>

Husain, W., The Judicialization of Politics in Pakistan: A Comparative Study of Judicial Restraint and its Development in India, the US and Pakistan (London: Routledge, 2018), <https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351190114>

Iacoviello, M. and Navarro, G., ‘Foreign Effects of Higher U.S. Interest Rates’, International Finance Discussion Papers, May 2018, <https://doi.org/10.17016/IFDP.2018.1227>

Imanaliyeva, A., ‘Kyrgyzstan: Court orders closure of RFE/RL’s local affiliate’, Eurasianet, 27 April 2023, <https://eurasianet.org/kyrgyzstan-court-orders-closure-of-rferls-local-affiliate>, accessed 11 May 2023

International IDEA, ‘Voter Turnout Database, Malaysia’, [n.d.], <https://www.idea.int/data-tools/country-view/221/40>, accessed 7 July 2023

International Telecommunication Union (ITU), ‘ICT Facts and Figures 2017’, July 2017, <https://www.itu.int:443/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/facts/default.aspx>, accessed 23 August 2023

Jain, A., ‘An attack on Indian democracy: On the bill to curb the independence of the Election Commission’, Verfassungsblog, 14 August 2023, <https://verfassungsblog.de/an-attack-on-indian-democracy>, accessed 22 August 2023

Joles, B., ‘The many trials of Imran Khan’, Foreign Policy, 5 April 2023, <https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/04/05/pakistan-imran-khan-court-cases-elections-corruption>, accessed 26 May 2023

Kaiku, P., ‘Not the Indo-Pacific: A Melanesian view on strategic competition’, The Interpreter, Lowy Institute, 18 April 2023, <https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/not-indo-pacific-melanesian-view-strategic-competition>, accessed 11 May 2023

Kothari, S. and Tawk, N., ‘How Asia can ease scarring from lower investment, employment and productivity’, IMF blog, 30 March 2023, <https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2023/03/28/how-asia-can-ease-scarring-from-lower-investment-employment-and-productivity>, accessed 11 May 2023

Landrin, S., ‘Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi neutralizes his main opponents’, Le Monde, 21 April 2023, <https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2023/04/21/indian-prime-minister-narendra-modi-neutralizes-his-main-opponents_6023799_4.html>, accessed 22 August 2023

Latiff, R., ‘Jailed Malaysian ex-PM Najib loses final bid to review graft conviction’, Reuters, 31 March 2023, <https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/jailed-malaysian-ex-pm-najib-loses-bid-review-graft-conviction-2023-03-31>, accessed 23 August 2023

Lau, C., ‘Hong Kong’s landmark transgender ruling: Will the rest of Asia now follow suit?’, South China Morning Post, 19 February 2023, <https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/lifestyle-culture/article/3210600/hong-kongs-landmark-transgender-ruling-will-rest-asia-now-follow-suit>, accessed 11 May 2023

Lawson, S., ‘Challenges for the Pacific Islands Forum: Between cohesion and disintegration?’, Australian Institute of International Affairs, 27 July 2022, <https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/australianoutlook/challenges-for-the-pacific-islands-forum-between-cohesion-and-disintegration>, accessed 28 June 2023

Lee, J., ‘Review: The end of UMNO?: Essays on Malaysia’s dominant party’, Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia, [n.d.], <https://kyotoreview.org/book-review/review-the-end-of-umno-essays-on-malaysias-dominant-party>, accessed 30 June 2023

Leesa-Nguansuk, S., ‘Social media plays key role in election’, Bangkok Post, 16 May 2023, <https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/2571277/social-media-plays-key-role-in-election>, accessed 24 May 2023

Masood, S., ‘Pakistan strengthens already harsh laws against blasphemy’, New York Times, 21 January 2023, <https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/21/world/asia/pakistan-blasphemy-laws.html>, accessed 11 May 2023

Mathur, S., ‘After 4 months, Rahul Gandhi returns as MP a day ahead of no-trust debate’, Times of India, 8 August 2023, <https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/after-4-months-rahul-gandhi-returns-as-mp-a-day-ahead-of-no-trust-debate/articleshow/102512300.cms?from=mdr>, accessed 22 August 2023

Meagher, P., ‘Anti‐corruption agencies: Rhetoric versus reality’, The Journal of Policy Reform, 8/1 (2005), pp. 69–103, <https://doi.org/10.1080/1384128042000328950>

Mulholland, J. and Sanit, A., ‘The weakening of Indonesia’s corruption eradication commission’, East Asia Forum, 28 January 2020, <https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2020/01/28/the-weakening-of-indonesias-corruption-eradication-commission>, accessed 25 May 2023

Needham, K., ‘Pacific Islands a key U.S. military buffer to China’s ambitions, report says’, Reuters, 20 September 2022, <https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/pacific-islands-key-us-military-buffer-chinas-ambitions-report-2022-09-20>, accessed 11 May 2023

Nikkei Asia, ‘Thailand’s move forward “will not back” Pheu Thai’s PM bid’, 15 August 2023, <https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Thai-election/Thailand-s-Move-Forward-will-not-back-Pheu-Thai-s-PM-bid>, accessed 22 August 2023

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), ‘UN expert welcomes verdict on Maria Ressa’s tax evasion case’, press release, 19 January 2023a, <https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2023/01/un-expert-welcomes-verdict-maria-ressas-tax-evasion-case>, accessed 11 May 2023

Other analyses describe Latin America and the Caribbean as the region of the world most likely to suffer the most significant shock. However, neither the IMF nor International IDEA separates out Latin America from less-affected North American nations for the purpose of this or other analyses. A further subdivision of the countries of the world could lead to a different conclusion.

Pandey, G., ‘India abortion: Why Supreme Court ruling is a huge step forward’, BBC News, 1 October 2022, <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-63086321>, accessed 25 May 2023

Perera, J., ‘A further erosion of moral legitimacy with blocking elections’, Colombo Telegraph, 14 February 2023, <https://www.colombotelegraph.com/index.php/a-further-erosion-of-moral-legitimacy-with-blocking-elections>, accessed 11 May 2023

Pettis, M., ‘1/6 Atif Mian explains Pakistan’s debt position and the terrible consequences for the Pakistani economy’, Rattibha, 24 May 2023, <https://en.rattibha.com/thread/1661235003798474753>, accessed 25 May 2023

Purnell, N. and Horwitz, J., ‘Facebook’s hate-speech rules collide with Indian politics’, The Wall Street Journal, 14 August 2020, <https://www.wsj.com/articles/facebook-hate-speech-india-politics-muslim-hindu-modi-zuckerberg-11597423346>, accessed 4 October 2023

Quah, J. S. T., Anti-Corruption Agencies in Asia Pacific Countries: An Evaluation of Their Performance and Challenges (Transparency International, 2017), <https://www.transparency.org/files/content/feature/2017_ACA_Background_Paper.pdf>, accessed 16 August 2023

RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty (RFE/RL), ‘Uzbekistan arrests top pharmacy official over child deaths blamed on cold syrup’, 10 February 2023, <https://www.rferl.org/a/uzbekistan-pharmacy-official-arrested-child-deaths/32265601.html>, accessed 11 May 2023

Rajagopal, K., ‘Register FIRs against hate speech even in absence of complaints, Supreme Court directs States’, The Hindu, 28 April 2023, <https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/register-firs-against-hate-speech-even-in-absence-of-complaints-sc-directs-states/article66789344.ece>, accessed 7 July 2023

Reporters Without Borders (RSF), ‘South Korea: RSF concerned by president’s hostile moves against public media’, 5 December 2022, <https://rsf.org/en/south-korea-rsf-concerned-president-s-hostile-moves-against-public-media>, accessed 11 May 2023

Runey, M., ‘Pakistan’s crisis shows that all politics are climate politics’, Democracy Notes [International IDEA blog], 2 February 2023, <https://www.idea.int/blog/pakistan%E2%80%99s-crisis-shows-all-politics-are-climate-politics>, accessed 11 May 2023

Safi, M., ‘India: High-profile candidates banned from election trail over hate speech’, The Guardian, 15 April 2019, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/apr/15/indian-party-leaders-banned-from-election-trail-over-hate-speech>, accessed 22 August 2023

The Scroll, ‘No power to ban political parties or candidates for hate speech, Election Commission tells SC’, 14 September 2022, <https://scroll.in/latest/1032804/no-power-to-ban-political-parties-or-candidates-for-hate-speech-election-commission-tells-sc>, accessed 7 July 2023

Setiawan, I., Pape, U. and Beschorner, N., ‘How to bridge the gap in Indonesia’s inequality in Internet access’, World Bank blogs, 13 May 2022, <https://blogs.worldbank.org/eastasiapacific/how-bridge-gap-indonesias-inequality-internet-access>, accessed 11 May 2023

Siddiquee, N. A. and Zafarullah, H., ‘Absolute power, absolute venality: The politics of corruption and anti-corruption in Malaysia’, Public Integrity, 24/1 (2022), pp. 1–17, <https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2020.1830541>

Siddiqui, Z. and Paul, R., ‘Some in Bangladesh election observer group said they regretted involvement’, Reuters, 22 January 2019, <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-bangladesh-election-observers-exclusi-idUSKCN1PG0MA>, accessed 30 June 2023

Sinpeng, A., ‘Digital media, political authoritarianism, and internet controls in Southeast Asia’, Media, Culture & Society, 42/1 (2020), pp. 25–39, <https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443719884052>

Solod, D., ‘A guide to the violent unrest in Uzbekistan’s Karakalpakstan region’, openDemocracy, 4 August 2022, <https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/protests-karakalpakstan-uzbekistan-former-soviet>, accessed 30 June 2023

Strangio, S., ‘Former Malaysian PM Muhyiddin Yassin charged with corruption’, The Diplomat, 10 March 2023, <https://thediplomat.com/2023/03/former-malaysian-pm-muhyiddin-yassin-charged-with-corruption>, accessed 11 May 2023

Stubbs, T., Kentikelenis, A., Gabor, D., Ghosh, J. and McKee, M., ‘The return of austerity imperils global health’, BMJ Global Health, 8/2 (2023), e011620, <https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2022-011620>

Tan, N., ‘Electoral management of digital campaigns and disinformation in East and Southeast Asia’, Election Law Journal: Rules, Politics, and Policy, 19/2 (2020), pp. 214–39, <https://doi.org/10.1089/elj.2019.0599>

Thu, H. L., ‘How to survive a great-power competition’, Foreign Affairs, May/June 2023, 18 April 2023, <https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/beijing-survive-great-power-competition>, accessed 11 May 2023

Tiwary, D., ‘From 60% in UPA to 95% in NDA: A surge in share of opposition leaders in CBI net’, The Indian Express, 21 September 2022, <https://indianexpress.com/article/express-exclusive/from-60-per-cent-in-upa-to-95-per-cent-in-nda-a-surge-in-share-of-opposition-leaders-in-cbi-net-express-investigation-8160912>, accessed 22 August 2023

Umam, A. K., Whitehouse, G., Head, B. and Adil Khan, M., ‘Addressing corruption in post-Soeharto Indonesia: The role of the corruption eradication commission’, Journal of Contemporary Asia, 50/1 (2020), pp. 125–43, <https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2018.1552983>

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), ‘UN DESA Policy Brief No. 153: India Overtakes China as the World’s Most Populous Country’, 24 April 2023, <https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/publication/un-desa-policy-brief-no-153-india-overtakes-china-as-the-worlds-most-populous-country>, accessed 7 July 2023

Venkatesan, V., ‘How Surat Court cherry-picked an SC order to deny relief to Rahul Gandhi in defamation case’, The Wire, 22 April 2023, <https://thewire.in/law/how-surat-court-cherry-picked-a-sc-order-to-deny-relief-to-rahul-gandhi-in-defamation-case>, accessed 22 August 2023

Wee, S.-L., ‘Anwar, opposition leader for decades, is now Malaysia’s prime minister’, New York Times, 24 November 2022, <https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/24/world/asia/malaysia-elections-prime-minister.html>, accessed 30 June 2023

The Wire, ‘Bangladesh’s restriction on observers and media raises concerns before elections’, 28 December 2018, <https://thewire.in/south-asia/bangladesh-elections-restrictions-media-observers>, accessed 30 June 2023

Xiao, L., ‘What can we learn from China’s military aid to the Pacific?’, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) [WritePeace blog], 20 June 2022, <https://www.sipri.org/commentary/blog/2022/chinas-military-aid-pacific>, accessed 11 May 2023

Yap, K. L. M., ‘Pakistan could default without IMF bailout loans, Moody’s warns’, Bloomberg, 9 May 2023, <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-05-09/pakistan-could-default-without-imf-bailout-loans-moody-s-warns>, accessed 11 May 2023

Yoon, L., ‘South Korea court recognizes equal benefits for same-sex couple’, Human Rights Watch, 22 February 2023, <https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/02/22/south-korea-court-recognizes-equal-benefits-same-sex-couple>, accessed 11 May 2023

Zhu, M., ‘Najib Razak: Malaysia’s ex-PM starts jail term after final appeal fails’, BBC News, 23 August 2022, <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-62642643>, accessed 11 May 2023

—, ‘Breaking the cycle of failure in combating corruption in Asian countries’, Public Administration and Policy: An Asia-Pacific Journal, 24/2 (2021), pp. 125–28, <https://doi.org/10.1108/PAP-05-2021-0034>

—, ‘Cambodia: UN experts call for reinstatement of Voice of Democracy, say free media critical ahead of elections’, press release, 20 February 2023b, <https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2023/02/cambodia-un-experts-call-reinstatement-voice-democracy-say-free-media>, accessed 11 May 2023

—, ‘Centre moves new bill on appointment of Election Commissioners, CJI excluded from panel’, 10 August 2023, <https://thewire.in/government/new-bill-selection-of-election-commissioners>, accessed 22 August 2023

—, ‘China: Unprecedented nationwide protests against abuses. Xi consolidates power amid Covid-19, economic challenges’, 12 January 2023, <https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/01/12/china-unprecedented-nationwide-protests-against-abuses>, accessed 11 May 2023

—, ‘Concerns about free expression in South Korea with security law, restrictions on press freedom and anti-north activism’, CIVICUS Monitor, 1 December 2022c, <https://monitor.civicus.org/explore/concerns-about-free-expression-south-korea-security-law-restrictions-press-freedom-and-anti-north-activism>, accessed 9 July 2023

—, ‘Democracy Tracker Newsletter: Across Asia, advances in LGBTQIA+ rights’, June 2023a, <http://eepurl.com/itjQ4s>, accessed 29 June 2023

—, ‘Facebook services are used to spread religious hatred in India, internal documents show’, The Wall Street Journal, 23 October 2021, <https://www.wsj.com/articles/facebook-services-are-used-to-spread-religious-hatred-in-india-internal-documents-show-11635016354>, accessed 25 May 2023

—, ‘Measuring Digital Development: Facts and Figures 2022’, 2022, <https://www.itu.int:443/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/facts/default.aspx>, accessed 11 May 2023

—, ‘Myanmar: ASEAN’s failed “5-point consensus” a year on. Key countries should overhaul approach to junta’s atrocities’, 22 April 2022a, <https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/04/22/myanmar-aseans-failed-5-point-consensus-year>, accessed 11 May 2023

—, ‘Sri Lanka: Revoke sweeping new order to restrict protest’, 27 August 2022b, <https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/09/27/sri-lanka-revoke-sweeping-new-order-restrict-protest>, accessed 22 August 2023

—, ‘Thailand – May 2023’, Democracy Tracker, 2023b,<https://idea.int/democracytracker/report/thailand/may-2023>, accessed 7 July 2023