About the report

International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy Report reviews the state of democracy around the world over the course of 2020 and 2021, with democratic trends since 2015 used as a contextual reference. It is based on analysis of events that have impacted democratic governance globally since the start of the pandemic, based on various data sources, including International IDEA’s Global Monitor of Covid-19’s Impact on Democracy and Human Rights, and International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy (GSoD) Indices. The Global Monitor provides monthly data on pandemic measures and their impact on democracy for 165 countries in the world. The Global State of Democracy Indices provide quantitative data on democratic quality for the same countries, based on 28 indicators of democracy up until the end of 2020. The conceptual framework on which both data sources are based defines democracy as based on five core pillars: Representative Government, Fundamental Rights, Checks on Government, Impartial Administration and Participatory Engagement. These five attributes provide the organizing structure for this report.

This report is part of a series on the Global State of Democracy, which complement and cross-reference each other. This report has a regional focus, and it is accompanied by a global report and three other regional reports that provide more in-depth analysis of trends and developments in Africa and the Middle East; the Americas (North, South and Central America, and the Caribbean); and Europe. It is also accompanied by three thematic papers that allow more in-depth analysis and recommendations on how to manage electoral processes, emergency law responses, and how democracies and non-democracies fared based on lessons learned from the pandemic.

The GSoD conceptual framework

Concepts in The Global State of Democracy 2021

- The reports refer to three main regime types: democracies, hybrid and authoritarian regimes. Hybrid and authoritarian regimes are both classified as non-democratic.

- Democracies, at a minimum, hold competitive elections in which the opposition stands a realistic chance of accessing power. This is not the case in hybrid and authoritarian regimes. However, hybrid regimes tend to have a somewhat more open—but still insufficient—space for civil society and the media than authoritarian regimes.

- Democracies can be weak, mid-range performing or high-performing, and this status changes from year to year, based on a country’s annual democracy scores.

- Democracies in any of these categories can be backsliding, eroding and/or fragile, capturing changes in democratic performance over time.

- Backsliding democracies are those that have experienced gradual but significant weakening of Checks on Government and Civil Liberties, such as Freedom of Expression and Freedom of Association and Assembly, over time. This is often through intentional policies and reforms aimed at weakening the rule of law and civic space. Backsliding can affect democracies at any level of performance.

- Eroding democracies have experienced statistically significant declines in any of the democracy aspects over the past 5 or 10 years. The democracies with the highest levels of erosion tend also to be classified as backsliding.

- Fragile democracies are those that have experienced an undemocratic interruption at any point since their first transition to democracy.

- Deepening authoritarianism is a decline in any of the democracy aspects of non-democratic regimes.

For a full explanation of the concepts and how they are defined, see Table 6 on p. 8 of the summary methodology.

Acknowledgements

This report was written by Leena Rikkila Tamang and Mark Salter, with contributions by Amanda Cats-Baril, Alberto Fernandez Gibaja and Antonio Spinelli, under the supervision of Kevin Casas-Zamora, Seema Shah and Annika Silva-Leander. It was developmentally edited by Jeremy Gaunt. Feedback and inputs on the report draft were provided by external peer reviewers Tom Gerald Daly, Imelda Deinla and Peter Ronald deSouza, and member of International IDEA’s Board of Advisers, S. Y. Quraishi.

International IDEA staff who provided feedback to draft versions were Sead Alihodžić, Marcus Brand, Alberto Fernandez Gibaja, Alexander Hudson, Nyla Prieto, Seema Shah and Annika Silva Leander. Alberto Fernandez Gibaja, Alexander Hudson and Joseph Noonan produced all the graphs in the report. Many thanks to Benjamin Gelman, Gentiana Gola, Anika Heinmann and Maud Kuijpers for their invaluable fact- and reference checking.

Foreword

The outbreak of Covid-19 in 2020 has severely challenged the democracy credentials of governments worldwide. Public health orders, crafted to lessen deaths and serious illness, have restricted human freedoms.

Citizens would normally protest such restrictions, but in the spirit of ‘we are all in this together’ citizens in Asia and the Pacific have generally cooperated and complied.

As Covid is curtailed, governments are incrementally uplifting the orders.

However, none of this scenario applies to my country, Myanmar.

Coup leader General Min Aung Hlaing has let Covid run rampant country-wide, has appropriated oxygen and vaccines away from citizens, and has enabled Covid to spill over national borders.

Civil and political freedoms have been most cruelly stripped bare and not for the health needs of our citizens, but for mere power grab.

The 1 February 2021 military coup changed the course of democratic trajectory in Myanmar. The coup forced the members of the elected Parliament to swear in virtually and to form the Committee Representing the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH) to continue representing the will of the people of Myanmar.

International IDEA’s report, The State of Democracy in Asia and the Pacific 2021, paints a picture of the state of democracy in Asia and the Pacific, looking back in time to when the pandemic started in early 2020.

Political leaders, journalists, judges, religious and sexual minorities, and activists are increasingly harassed and persecuted. Elections are being delayed and electoral frameworks manipulated. Geopolitical tensions are on the rise.

And yet, I remain optimistic about democracy’s resilience. As the GSoD report accounts, the popular demands for democratic freedom and political reform are not muted, not even in the face of brutal force. Many of these movements are led by youth, among whom regional solidarity is self-evident.

The report goes further than describing the state of democracy, providing a set of useful recommendations for governments, policymakers and those working on democracy support.

Governments around the region should take a hard look at the measures taken to safeguard democracy, especially in times of emergencies.

At the time of writing this foreword, I am forced to remain out of General Min Aung Hlaing’s murderous reach, as are so many of my Parliamentary colleagues. Many remain in arbitrary detention; many have lost their lives.

We remain determined to stay connected with our people, to bring about economic assistance to those participating in the civil disobedience movement, and Covid-19 vaccines to those in need.

We aim to restore democracy and to reimagine a democracy that is more inclusive and participatory, and which can deliver freedom and welfare, justice and a sense of a brighter future.

To restore a democracy that delivers a federal democratic union, and that delivers real and lasting peace with Myanmar’s large ethnic nationalities population, who have suffered terribly in the region’s longest running civil wars, wars waged by General Min Aung Hlaing and those before him.

Democracy will prevail.

Zin Mar Aung

Minister for Foreign Affairs

National Unity Government (NUG)

Member of CRPH (Committee Representing the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw)

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic initially broke out in the Asia and the Pacific region in late 2019, with the first cases in Wuhan, China.

The pandemic has served as a magnifier of pre-existing democratic strengths and weaknesses within governing systems around Asia and the Pacific. High-performing and economically strong democracies (Australia, New Zealand) and some mid-range democracies (Japan, the Republic of Korea, Taiwan, Timor-Leste) continue to maintain their scores, if not without challenges. The major decliners among democracies were India, Indonesia, the Philippines and Sri Lanka.

In the majority of cases, the region’s hybrid and authoritarian regimes have tightened their grip on society in response to the pandemic. For example, Cambodia, which has never fully transitioned to democracy, suffered from deepening authoritarianism during 2020. China also declined, particularly on Fundamental Rights and Checks on Government. Uzbekistan, however, has improved its scores in Fundamental Rights, Checks on Government and Impartial Administration since 2017.

China’s economic and political influence in the region has continued to grow, not least through its Belt and Road Initiative. The initiative is an ambitious foreign and economic project by President Xi Jinping, outlining a combination of economic and strategic drivers. The country has also tried to offer itself as a viable alternative to democratic governance, and the pandemic afforded Beijing the opportunity to influence regional and global geopolitics—in particular via its growing ‘vaccine diplomacy’ across Asia and globally.

Several countries in the region also continued to experience a rising tide of ethnonationalism and an increasing role for military and security forces in politics and in civilian governance. Additionally, a range of pan-regional factors added to the stresses on democratic progress in the region, including migrant movements and climate-change-induced crises such as floods and droughts.

Aside from Fundamental Rights, Checks on Government—as in those upheld by parliaments, the judiciary and the media—has suffered the most serious decline over the last five years, therefore posing a major risk to the continuing consolidation of democracy in the region.

Despite these challenges, in its response to the Covid-19 pandemic, the Asia and the Pacific region has demonstrated impressive democratic resilience and innovation. Several countries of the region were relatively well equipped to respond, due to their experience with previous epidemics: SARS in 2003 and MERS in 2015. In contrast to other regions, several countries already had legal and institutional frameworks in place effectively tailored to dealing with global health emergencies and were able to activate these rapidly in response to the ongoing challenges posed by the pandemic.

Importantly, some of the effective responses to the Covid-19 pandemic made by several Asian countries have highlighted the fact that such a crisis can be contained through an effective, timely and broad-based approach that also respects legal constraints and coordinates across an array of elected and unelected institutions. The region provides examples of cases where executive effectiveness has been strengthened through democracy rather than through its curbing, offering important insights and inspiration for how to enhance democracy’s global appeal and functioning.

This report offers lessons and recommendations that governments, political and civic actors, and international democracy assistance providers should consider in countering the concerning trend of democracy’s erosion seen across Asia and the Pacific, and in fostering its resilience and deepening through the promotion of positive trends and innovations.

Chapter 1. Key facts and findings

The extraordinary diversity of the Asia and the Pacific region—not just culturally, but in terms of size of countries, systems of governance, and levels of economic development—has shown up clearly in the various responses to the Covid-19 pandemic made by countries around the region. There are examples of how the pandemic has been managed while maintaining respect for fundamental rights and legal principles, but also cases where governments entrenched their power and/or where democratic backsliding was observed.

As such, following the pandemic, the region’s democratic divide has deepened—with some countries performing exceptionally well, and others struggling significantly to maintain democracy. All in all, the pandemic tended to exacerbate and resurrect trends in democratic performance.

CHALLENGES

- Attempting to contain the outbreak of the pandemic prompted most countries in the Asia and the Pacific region to restrict freedom of movement. All 32 countries imposed some restrictions, ranging from full lockdowns to limits on the size of public gatherings, and in some cases, these were combined with longer-term anti-democratic tendencies. All democracies needed to seek balance between individual and collective rights.

- Freedom of expression came under attack across the region, in both democracies (such as the Philippines and Sri Lanka) and non-democracies (such as Cambodia and China)—with citizens arrested, excessive force used by the police, and criminal charges being imposed simply for publicly voicing criticism of official handling of the pandemic crisis.

- A noticeable continuation of a decline in democracy was recorded in India, Indonesia, the Philippines and Sri Lanka (as well as the democracy-ending military coup in Myanmar and stifling legal changes in Hong Kong). The hybrid regime in Singapore and the authoritarian regime in Viet Nam demonstrated unprecedented degrees of pandemic-response transparency, albeit while old habits of censoring and suppressing vocal critics remained.

- A trend towards intervention in politics by security forces was noted in both authoritarian regimes and democracies, in part because official pandemic responses relied heavily on such military institutions for operational and logistics expertise. It is likely that the enhanced role of the security forces will outlast the pandemic itself: the military has long played a pivotal role in politics in some countries in the region, such as Bangladesh, Pakistan and Thailand.

- Rising ethnonationalism, exacerbated by the stress of the pandemic, is undermining pluralism, increasing polarization and heightening conflict. The trend was most immediately noticeable in India, Indonesia and Sri Lanka, but there is a risk that economic damage from the pandemic and growing inequality may spread ethno-polarization further across the region.

- The pandemic has afforded the authoritarian regime in China the opportunity to influence regional and global geopolitics, both on account of its perceived effective handling of the pandemic, and via its growing ‘vaccine diplomacy’ offensive, particularly in the Global South. At the same time, the situation in China itself deteriorated, particularly in Civil Liberties and Checks on Government.

OPPORTUNITIES

- High-performing and economically strong democracies (Australia, New Zealand), and some mid-range democracies (Japan, Mongolia, the Republic of Korea, Taiwan, Timor-Leste) generally managed their responses to the pandemic while respecting democratic principles. No country escaped the difficult balancing of individual versus collective rights.

- Across the Asia and the Pacific region, the varied assaults on democratic freedoms intensified popular demands for political reform, including in Hong Kong, Myanmar, the Philippines and Thailand, triggering vocal pro-democratic responses rather than muting them.

- Throughout the region, the pandemic gave rise to electoral management advancements and innovations. These showed how elections can be managed in future, also during emergencies, by ensuring the independence of electoral management bodies (EMBs), robust legal frameworks, effective communication and use of special voting arrangements, among other things.

- Democracies, such as Australia, Mongolia, New Zealand, the Republic of Korea and Taiwan, provided crucial lessons to the rest of the world about how elections can be credibly managed under the restrictions imposed by Covid-19.

- Dealing with the pandemic offered a practical demonstration of the benefits that decentralized and multilevel government (Australia, India, Nepal) and inter-agency cooperation (New Zealand, Taiwan) can offer, combining local responsiveness, capacity and democratic accountability with collective and coordinated action.

Chapter 2. Overview of key trends

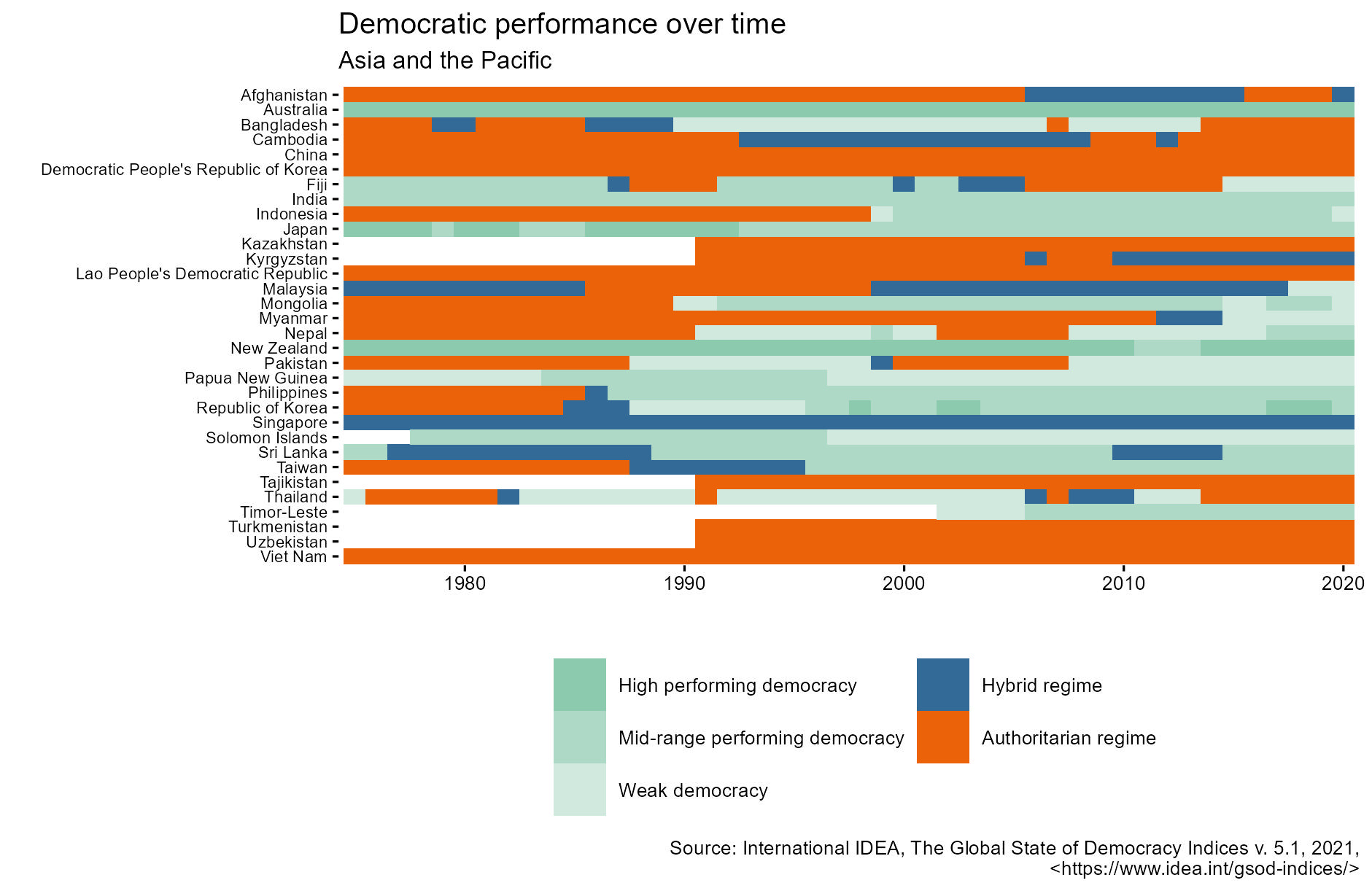

The Asia and the Pacific region boasts extraordinary diversity, both culturally and in terms of country size, governance traditions and levels of economic development. A similar diversity is seen in regime type and performance among the region’s democracies, as illustrated in Figure 1. Despite the notable diversity, in recent years most countries have maintained their regime type, with only one transition to democracy (Malaysia 2018) and one movement from authoritarian to hybrid regime in Afghanistan (2020), as defined by the Global State of Democracy (GSoD) Indices (with data up to the end of 2020). In 2021, Myanmar became an authoritarian regime following the military coup, the first democratic breakdown in the region since 2014. As of August 2021, the situation in Afghanistan was deteriorating, with the Taliban taking over and the elected government collapsed.

Figure 1.

Within countries defined as democracies, however, diverse shifts in democratic performance create a complex picture, as illustrated in Figure 2. On one side, several countries in Asia and the Pacific have suffered declines in their general democracy performance scores, while on the other side several advances have also been seen.

Figure 2.

Box 1. Myanmar’s regression to authoritarian regime

To date, the most dramatic democratic reversal in the region occurred in Myanmar, where the armed forces (the Tatmadaw) seized power in early February 2021. The Tatmadaw declared the November 2020 election result null and void and arrested the elected government’s leadership, as well as election commissioners, members of parliament and political parties, pro-democracy activists, journalists, etc. While the people of Myanmar have refused to accept military rule and continue to mount impressive protests, the Tatmadaw has repressed resistance, even in the online sphere, with arrests and often fatal violence. Showing disregard for international standards and statements of condemnations, and faced with continued resistance, the Tatmadaw has resorted to imposing a climate of terror and repression on the civilian population, regularly carrying out house raids, indiscriminate beatings and indefinite detentions, while also severely limiting popular access to print and electronic media. Meanwhile, the democratically legitimate representatives have formed an alliance with ethnic organizations and civil society to establish a National Unity Government, which seeks to restore democracy and rebuild the state without preserving a special political status for the military.

In the last five years, the scores of some countries, such as India, Indonesia, the Philippines and Sri Lanka, have worsened, although they have retained their status as democracies according to the GSoD Indices (Figure 3). These decreases respond to a gradual deterioration in several aspects of democracy, even if in most cases their elections generally remain competitive. Conversely, the region has also witnessed various advances, both from already established democracies such as the Republic of Korea, and from authoritarian regimes such as Uzbekistan and Thailand. These positive shifts indicate how even seemingly intractable, authoritarian regimes are not static and emphasize the importance of supporting even the most emergent voices for democracy in these contexts.

Box 2. China

China’s scores on Civil Liberties and Checks on Government have further descended over the last three years. The Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) internal strength has relied on its capacity to renew/rotate the leadership of the party—and therefore the country—on a regular basis. China has had a two-term limit for its presidency since the 1990s, which meant that President Xi Jinping was due to step down in 2023. This policy was changed, however, when the annual National People’s Congress of 2018 removed the tenure limitation and voted to include President Xi’s name and ideology in the party’s constitution, elevating his status to the level of its founder, Chairman Mao Zedong. While this centralization of power puts him in an exceptional position to advance difficult reforms, such as against corruption, an increased use of national mobilization and top-down orders may also stifle China’s adaptability and entrepreneurship—the very qualities that helped the country navigate its way through obstacles in the past. Time will tell whether doing away with term limits, and with it the opportunity to renew and refresh leadership of the party and in the country, will have an impact on the CCP’s resilience and on people’s support for the party, and may plant the seeds for future movements for larger-scale change.

Figure 3.

Chapter 3. Representative Government

The GSoD Indices use the Representative Government attribute to evaluate countries’ performance on the conduct of elections, the extent to which political parties are able to operate freely, and the extent to which access to government is decided by elections. This attribute is an aggregation of four subattributes: Clean Elections, Inclusive Suffrage, Free Political Parties and Elected Government.

3.1 Elections: Pre-pandemic

While high-performing and mid-range democracies have proven resilient in their delivery of generally competitive and clean elections, the region remains characterized by significant heterogeneity in terms of:

- Integrity of elections. The quality, inclusiveness, political freedom, competitiveness and resulting legitimacy of elected governments vary substantively from country to country.

- Scale of electoral processes and size of electorates engaged. There are significant disparities in both suffrage and operational complexity between populous countries (India, Indonesia) and others with small but dispersed populations (several Pacific Islands).

- Levels of voter turnout. Voter turnout continues to be extremely diverse, irrespective of the type of regime and quality of elections delivered. In the last 10 years, some countries in the region (Afghanistan, Japan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan) have consistently recorded extremely low voter turnout rates in recent electoral cycles, defined as slightly above or below 50 per cent participation of those eligible to vote. In other countries, voter turnout has either experienced minor overall increases (India), slightly declined (Maldives), or shown marked increases (Bangladesh, Bhutan, Indonesia, the Philippines, the Republic of Korea, Taiwan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Timor-Leste).

Paradoxically, the quality of elections has a direct influence on the resilience of both types of regimes: while democratic regimes are reinforced by genuine elections, weak democracies and authoritarian regimes also sustain themselves through technically or politically flawed elections.

In 2020, the regional outlook for the quality of elections in Asia and the Pacific was positive: at that time, nearly half (8) of the region’s democracies displayed high levels of Clean Elections, while 56 per cent of democracies had reached mid-range levels (Figure 4). High levels of Clean Elections could be found not only in three older democracies (Australia, Japan and New Zealand), but also in three early third-wave democracies (Indonesia, the Republic of Korea and Taiwan) and a newer democracy (Timor-Leste), with their electoral management bodies (EMBs) progressively acquiring and consolidating essential skills and capacities in the technical delivery of credible elections. Sri Lanka, which has experienced democratic fragility and weak democratic performance, recorded increased levels of Clean Elections in 2019, achieving the high performance mark. In contrast, Clean Elections in India, Nepal and the Philippines has, over the last five years, declined.

Figure 4.

Several challenges and persisting weaknesses have continued to place limitations on the integrity and competitiveness of electoral processes in the region. They include: protracted violent conflict (Afghanistan, Myanmar); volatility of political contexts (Malaysia, Sri Lanka); recurrent military interference in the political sphere (Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand); executive overreach and weakening checks and balances (India, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippines); and lack of EMB independence, intimidation and repression of opposition parties, and restrictions or persecution of their candidates by the incumbent government (Cambodia).

Furthermore, the impact of the constant social and economic change, demographic growth and migration that characterize the region continues to impose limitations on greater electoral inclusion, participation and representation. This phenomenon is particularly evident in South Asia, the world’s most densely populated subregion. With a combined population of nearly two billion people, seven of the eight countries in this subregion—that is, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and the Maldives (with the only exception of Bhutan)—have either limited, selective or no special voting arrangements in place. As a result, anyone who is absent from their constituency of registration on election day—including internal and international migrants, refugees and internally displaced persons—continues to be deprived of their electoral franchise.

As is indicated in Figure 5, Central Asia and South East Asia continue to record the largest share of authoritarian and hybrid regimes in the region, as the quality and integrity of elections held in several countries of these subregions (Cambodia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkmenistan) have continued to decline. With electoral processes and outcomes designed and implemented to provide a democratic façade for non-democratic regimes, they lack basic levels of credibility, transparency, competitiveness, legitimacy and integrity. While the poor quality of elections remains a challenge to deepening democracy in the region, instances of electoral fraud and manipulation have sparked political crises—such as protests and unrest in Kyrgyzstan—an indication that such malpractices can no longer be perpetrated as easily and without serious consequences.

Figure 5.

While some hybrid and authoritarian regimes have held elections regularly—for example, Bangladesh—these processes have not been assessed as fully competitive, independent, inclusive or free from irregularities. Additional vulnerabilities limiting the quality, competitiveness, inclusivity and representativeness of elections in the Asia and the Pacific region include: the continued exclusion of marginalized groups and the political under-representation of women (particularly in the Pacific where, for example, Papua New Guinea and Vanuatu have not a single female representative in their parliaments); the complex information or technological environments around elections; and the increased mobility of voters as a result of economic crises, demographic growth, political instability and increasingly extreme natural disasters associated with climate change.

On top of these long-term structural vulnerabilities, the pandemic has placed even further strains on electoral processes in the region. The most notable features characterizing elections held to date across the Asia and the Pacific region under the pandemic can be clustered as follows:

- postponed national elections—either successfully held later (e.g. Bangladesh, Kiribati, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Sri Lanka) or where no new date was set (Pakistan);

- postponed elections followed by changes in electoral legal framework (Hong Kong) or state censorship of media (Singapore);

- the use of social media and other digital platforms for disinformation and digital interference, including the use of ‘bots’ and ‘trolls’ to discredit political opponents (India, Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand); and

- digital campaigning innovations that opened new ways of abusing state resources for electoral purposes, including instances of access and use of personal data by incumbent parties for election campaigning (Malaysia).

Despite the challenges posed by Covid-19, in Asia and the Pacific a total of 23 national and 13 local or regional elections have been held on schedule, allowing the region to model globally important lessons learned, safeguards and innovations in the management of elections during a pandemic (see Table 1).

Table 1.

In particular, the positive practices and experiences recorded by some countries in the region (chief among them Australia, Mongolia, New Zealand and the Republic of Korea) have reinforced awareness of the need to focus on managing elections as long-term processes rather than one-off events, as well as realigning assistance efforts towards building more resilient and sustainable electoral frameworks, institutions and processes. At the same time, these elections have resulted in renewed attention to pre-existing but long unattended challenges, while also opening the door for innovation, stimulating creative approaches and new technological solutions. Without the significant pressures imposed by the pandemic crisis, these measures arguably would not have been conceived or implemented. The most notable innovations include the use of augmented reality (AR) technology for virtual election campaigning in the Republic of Korea, and the use of online campaigning resulting in more female and minority candidates being elected, as was the case in local government elections in the Australian state of Victoria.

Likewise, social media has been both a source of ‘campaigning and defining electoral discourseʼ and a source of ‘disinformation and trollingʼ. WhatsApp groups have been very effective in both, for example, in the massive Indian elections.

The experiences of EMBs in the region have provided new examples and set higher performance standards globally, inspiring other EMBs to prioritize and bolster collaboration and expand their regional cooperation and knowledge-sharing efforts. Most importantly, such experiences have accelerated the trend of moving the act of voting away from the polling stations. The drive of these countries to make voting safer by adopting or scaling up special voting arrangements, such as early or absentee voting methods, also made the electoral franchise generally easier, more convenient and accessible to voters.

3.2 Persisting and new challenges

Looking ahead, several challenges can be expected to continue limiting the conduct of clean elections and the formation of representative governments in Asia and the Pacific:

- Continued disruptions to the electoral cycle. Further disruptions to the inclusiveness and integrity of elections in the region may be expected as a result of: increasing natural disasters and other extreme weather events associated with climate change; malicious foreign interference; and the exploitation of future crises by authoritarian leaders to undermine democratic institutions and processes. These disruptions may increase political disillusionment and possibly lead to voter apathy.

- Sustaining advances and innovations throughout upcoming electoral cycles. Some of the legal, regulatory and procedural electoral advances and innovations under the pandemic are improvements that cannot be reversed. Consequently, their regulation, refinement and sustained use in the long term may prove more difficult for EMBs, as their swift introduction as a reaction to the Covid-19 crisis leaves them relatively unintegrated into broader electoral contexts.

- Further erosion of public and stakeholder trust in independent, transparent and accountable management of future electoral processes. Issues associated with this phenomenon range from authoritarian populism, the rise of new nationalism and exacerbated political polarization due to the global spread of disinformation. Adding to this erosion is the weakening of EMBs by the executive through partisan appointments. Furthermore, the adoption of special voting arrangements in contexts with unsuitable or excessively rigid frameworks, systems and processes—or if they are introduced hastily, without consultation and consensus—may lead to contested electoral outcomes. These factors can potentially combine to heighten public expectations and stakeholder demands for error-free, transparent, modern and efficient administration of future elections.

- Limitations on electoral inclusion, participation and representation imposed by constant social change and economic and demographic growth. Expansion of migration—both internal and external, with increasing flows within and outside of Asia and the Pacific, and inside individual countries—will reinforce the need to address greater voter mobility and ensure the broader electoral inclusion of many affected groups who are still largely disenfranchised.

Box 3. Augmented reality as a campaign method

The outbreak of the pandemic changed conventional methods of campaigning in the Republic of Korea. Political parties and candidates shifted to online and digital technology, mainly video messages disseminated through social media platforms, SMS and mobile phone apps. Some candidates employed augmented reality (AR) technology to remotely and virtually interact with their supporters. For example, some used AR to allow their supporters to digitally express their endorsement of election pledges through a mobile application and their phone cameras. Other candidates launched AR mobile services that enabled voters to digitally ‘meet’ and interact with a 3D animated character from the party—this character could appear on photos and videos taken by users, who could then share these with other supporters.

Chapter 4. Fundamental Rights

The Fundamental Rights attribute aggregates scores from three subattributes: Access to Justice, Civil Liberties, and Social Rights and Equality. Overall, it measures the fair and equal access to justice, the extent to which civil liberties such as freedom of expression or movement are respected, and the extent to which countries are offering their citizens basic welfare and political equality.

Over the last five years, scores on Fundamental Rights have remained relatively stable in the Asia and the Pacific region. Uzbekistan has shown the highest positive increase on this attribute, followed by Malaysia and the Republic of Korea. The most significant declines have taken place in Indonesia, followed by Cambodia, India and the Philippines. While Myanmar had shown consistent improvements up until 2020, the military coup of February 2021 has drastically backtracked this progress. Similarly, fundamental rights are under threat in Afghanistan after the Taliban takeover. Figure 6 demonstrates the change in Fundamental Rights scores between 2015 and 2020.

Figure 6.

4.1 CIVIL LIBERTIES

Civil liberties generally, as well as legal guarantees of personal liberty and security specifically, were impacted by responses to the pandemic, with the majority of governments in the region taking measures to temporarily restrict civil liberties in order to contain the spread of Covid-19. Such measures have included restrictions on freedom of assembly, expression, movement and religion. Some of these measures may be justified in terms of safeguarding public health, provided that they are implemented within a constitutionally or legislatively defined state of emergency (SoE) (see next section) and are therefore limited in scope and duration.

However, beyond lockdowns, curfews and other precautionary public health safeguarding measures, concerning attacks on civil liberties were noted around the region, including large numbers of citizens arrested, the use of excessive police force, and/or issuing of criminal charges simply for publicly voicing criticism of the official handling of the crisis. In some countries, notably India and the Philippines, human rights violations resulted in deaths, chiefly as a consequence of heavy-handed enforcement of lockdowns and curfews.

At least 23 countries in the region (77 per cent) have passed laws or used existing ones to restrict freedom of expression during the pandemic. In 18 of these cases, the measures taken are classified as ‘concerning’ by the Global Monitor of Covid-19’s Impact on Democracy and Human Rights, making Asia and the Pacific the region where freedom of expression has seen the most restrictive measures to date during the pandemic. Measures have often been justified by the alleged need to combat virus-related disinformation. Yet, actions and laws have been directed at journalists, news outlets, citizens, activists or opposition politicians, who have been harassed, fined, detained, arrested, investigated or deported for their reporting.

Box 4. Losing Hong Kong

In Hong Kong, harsh new security legislation, widely criticized as curtailing freedom of speech and assembly, was introduced in June 2020. In early December 2020, Joshua Wong, Agnes Chow and Ivan Lam, a trio of young high-profile democracy activists and veterans of the 2014 ‘umbrella movement’, were sentenced to between 7 and 13 months’ imprisonment for ‘unauthorized protest’ that took place over a year before, when the new legislation was not in effect. Ten days later, they were joined by billionaire Hong Kong newspaper owner Jimmy Lai, a long-standing supporter of the territory’s pro-democracy movement. Following his arrest in August 2020, Lai was accused of conspiracy to endanger national security in cooperation with unnamed foreign powers. Under the new legislation, trials can be held in secret and without a jury, and cases can also be taken over by mainland authorities.

4.1.1 State of emergency measures

State of emergency (SoE) measures are foreseen by most constitutions and legal frameworks in countries around the world. Often, there is a set procedure for how to declare an SoE, which can trigger special government processes and allow for the restriction of citizen’s rights. Democratic principles, such as separation of powers and due process, should be mainstreamed in the application and monitoring of SoEs. As noted in the GSoD thematic paper on SoEs, constitutions can be both enablers and disablers of a state’s capacity to effectively respond to an emergency within an accountable, democratic framework. The use of SoE measures in the region can be broadly clustered into the following categories:

- Constitution-based emergency powers. This refers to countries whose constitution specifically provides for the declaration of an SoE—for example, India, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Solomon Islands and Timor-Leste.

- Emergency powers in existing legislation. This refers to countries where emergency powers are provided for not in the constitution but in other pieces of health- or crisis-related legislation—for example, Japan, the Republic of Korea and Singapore (public health laws); Myanmar and Vanuatu (public disaster laws).

- Other legislation-based powers. In Thailand’s case, this process involved a repurposing of legislation previously enacted to deal with national security issues for the purposes of combating the pandemic. Political controversy over this approach centres around a 2005 Emergency Decree that, as well as still being in force, provided the basis for a 2020 Covid-19 Decree. While the 2005 Decree was approved by Parliament, its invocation and use are now solely at the Prime Minister’s discretion, and the House cannot review or scrutinize his decisions under the decree, leaving only judicial review as a (modest) measure of legal recourse.

Since January 2020, 37 per cent of countries (12) in Asia and the Pacific have declared a national SoE to curb the pandemic—significantly less than the global regional average of 59 per cent (Figures 7 and 8). At the same time, reflecting global trends, more democracies than non-democratic regimes declared SoEs in the region. This dynamic may reflect the idea that democracies consider it necessary to go through the procedural step of declaring an SoE before moving to restrict human rights. Almost half of the region’s democracies (8 out of 18) have done so, compared with only 4 out of the 14 hybrid and authoritarian regimes (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Thailand and Uzbekistan).

Figure 7.

Figure 8.

Box 5. Assessing the need for continued SoEs

While it is tempting to see the extension of SoEs as inherently dangerous for democracy, there is a need to take a more nuanced approach to assessing government decisions to renew them. For example, the SoE declared in March 2020 in the Philippines was extended to run until September 2021, making it the longest-running in the world. While some have interpreted the long-running SoE as a sign that democracy is at risk, it is critical to note that—15 months into the pandemic—the Philippines was experiencing its worst surge of infection cases. In April 2020, the average number of daily cases was 213, which rose to 2,169 at the end of 2020; by April 2021 the daily case load was at approximately 10,400, with intensive care units at 84 per cent capacity in Manila. Given these developments, it is hard to question the need for the country to extend its SoE, although there is doubt over how effective the SoE has been in restricting the spread of the virus. As experiences in the Philippines and elsewhere across the region indicate, SoE-derived measures, such as lockdowns, do not, in and of themselves, contain or eliminate the virus. Adequate resourcing and prioritization of dedicated health and medical measures, such as widespread testing, contact tracing, quarantine and so on, are equally—if not more—important in this context. In the case of the Philippines, it is also important to note that the Duterte Government used SoE restrictions as the basis for going after some of its chief critics, including by labelling them as enemies of the state.

While some countries enacted amendments to strengthen their legal frameworks and institutional capacities to respond to Covid-19, concerns were also raised that governments pursued amendments that may have weakened oversight over their emergency powers. For example, in Papua New Guinea, where the legislature has strong emergency oversight powers, in July 2020 the Government legislated a new National Pandemic Act that ‘essentially replicates the SOE scheme under the Constitution but without the elaborate parliamentary oversight over the operations of Government and key emergency personnel during the emergency period’. The opposition has taken the issue to court, arguing that ordinary legislation cannot reduce the constitutional duties of the executive.

In Sri Lanka, the Government avoided declaring an SoE of any type. Instead, the administration of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa chose to declare an extended curfew in March 2020, and to manage its pandemic response through a number of dedicated taskforces directly appointed by—and solely answerable to—President Rajapaksa. Moreover, the taskforces are chiefly composed of senior military figures, current and retired. In the absence of an SoE, however, the legal basis and constitutionality of an extended curfew were unclear. The Government also relied on the Quarantine and Prevention of Diseases Ordinance 1897 (as amended). Regulations issued under that ordinance have guided public health authorities and law enforcement authorities in designing responses to pandemic control. Alongside questions regarding the competency of military leaders to oversee the response to a public health emergency, the negative impact on civil liberties of a militarized pandemic response structure remains a subject of lively and widespread commentary and debate within the country.

Context is relevant—even with regard to the use of legal powers such as SoEs. Common to the countries of Japan, the Republic of Korea and Singapore is that, despite the use of laws to underpin their response, the need for enforcement mechanisms was low. In this context, it is suggested that the populations of these countries appeared to be generally aware of applicable laws and their intent, and were generally willing both to accept that such declarations were made in good faith and to comply with them. This observation was also generally the case in Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific Island countries, where most people accepted what in some cases were quite strict lockdowns (for example, the Australian state of Victoria, which endured many months of hard lockdown from July 2020), with only small pockets of resistance.

Box 6. A regional exception

Taiwan offers an interesting contrast in its approach to pandemic-related legislation. Unlike many countries, it did not enact SoE-type legislation and was careful to ensure that, for example, precautionary moves to extend the New Year 2020 holiday were implemented in keeping with earlier constitutional court rulings on the interpretation of post-SARS legislation. Nonetheless, concerns have been voiced over the authorities’ collection of information regarding the movements of individual citizens during the pandemic. Issues of concern include: smartphone software used to track individuals for the purpose of establishing infection transmission chains via contact tracing, and the potential centralization of databases containing official information regarding individual health, travel history etc. Responding to such concerns, Minister of Health and Welfare Chen Shih-chung claimed that collected information could only be used for pandemic-related investigations, and at the express request of health authorities. He further suggested that people should be informed as to what type of information was being collected, its purpose, the person or body responsible for its collection, and how (and for how long) the information would be used.

4.2 SOCIAL RIGHTS AND EQUALITY

4.2.1 Gender Equality

Over the last 40 years, Asia and the Pacific has made significant gains in gender equality, moving from borderline low levels on the GSoD measure of Gender Equality in 1975 to mid-range levels in 2020. Progress has, however, stagnated over the last 10 years. In terms of women’s political representation, Asia and the Pacific’s average of 20 per cent of women in parliament remains behind all other regions—with the Pacific Islands, for example, scoring only 6.4 per cent. At the country level, the proportion of female legislators ranges from 48 per cent in New Zealand to 0 per cent in Papua New Guinea, Vanuatu and Micronesia (latter two not covered by the GSoD Indices). Among the older democracies, Japan’s legislature has only 10 per cent women, and Sri Lanka’s 5.4 per cent (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Box 7. Representation of women at the subnational level

Some of the opportunities for women are found at the subnational levels—for example, there was an increase in female representation in the Australian state of Victoria’s local council elections in October 2020, despite constraints imposed by the pandemic. Victoria’s local government is now the closest to gender parity of any local government in Australia, with 43.8 per cent of councillors female, and an express aim of achieving 50 per cent by 2025. In Nepal, mayors and deputy mayors, in place since 2018, as part of the new federal structure, have been key actors in ensuring that pandemic-related interventions are both gender-sensitive and inclusive. The majority of Nepal’s elected deputy mayors are currently women due to a quota system which necessitates that the mayor and deputy mayor are of different genders.

Factors explaining increases in women’s representation relate to institutional design choices, such as the introduction of gender quotas (Afghanistan (with reserved seats), Nepal, Samoa); constitutional reforms (Indonesia, Nepal, Timor-Leste); reforms in electoral systems towards proportional systems (Fiji); the introduction of party lists in view of excluded groups (the Philippines); voluntary political party quotas, also for the LGBTQIA+ communities (Australia); and broader modernization and changes in women’s socio-economic status due to increased education and improved health.

Box 8. The #MeToo movement has also made its way to Asia and the Pacific

While the movement has not led to systemic or societal changes in much of the region, its effect is nonetheless being felt. In Australia, debates about political violence against women and a still elusive full gender parity are very much on the political agenda. In some countries, such as China and the Republic of Korea, women are protesting sexual harassment and abuse at workplaces.

Electoral gender quotas have been particularly successful when their design has been part of a broader momentum of democratic transition with public support (Nepal, Timor-Leste), and less successful when introduced with little political enthusiasm (Samoa) and in the context of deep political polarization and democratic decline. This phenomenon was seen in 2008 in Bangladesh, where there was an effort to reform the parliamentary reserved seats system. The caretaker government in power at the time had proposed a 33 per cent quota for women in parliament via a direct election, and a separate quota for cabinet members. However, due to strong and vocal opposition by senior Islamic scholars and clerics, the proposal was abandoned. Similarly, moving from first past the post to a more proportionate system increased women’s representation in Fiji, but not in Sri Lanka.

Factors explaining low regional progress in women’s political representation include: (a) a high number of countries with one-party systems (non-democracies) characterized by male dominance; (b) politically divided societies; (c) the importance of money in pursuing a career in politics; (d) political violence against women in politics; and (e) persistent, conservative socio-cultural factors. To date, the parity laws spearheaded in Latin America have not been seriously considered in the region.

Box 9. Women of Afghanistan

Afghanistan’s score on Gender Equality in the GSoD data in 2020 was 0.31. Although modest and still below regional averages, this was the country’s all-time high, with significant improvement on the 2001 score, which was 0. However, on 13 August 2021, the UN Secretary-General, António Guterrez, said in a press statement that he was ‘deeply disturbed’ by reports of the Taliban imposing severe restrictions on human rights in the areas under their control, particularly targeting women and journalists. The policy pronouncements of the Taliban Government with respect to certain issues, such as women’s education, work, public mobility and so on, are not in line with universal human rights.

The pandemic’s gendered consequences

Gender equality is a prime example of the pandemic’s magnifying impact on existing tendencies, and the risk of reversal of progress made on the issue is real. Specific gendered consequences notably include an increased burden for women in the home (unpaid care, domestic work) and rising levels of domestic violence. Already, in 2019, more than 37 per cent of all women in South Asia, 40 per cent in South East Asia and an alarming 68 per cent in the Pacific had experienced some form of sexual or physical violence. Given the multiple economic, health, security and other stresses and shocks on women and girls resulting from the pandemic, advances in gender parity might be affected.

Women make up more than half of migrant workers in the region, and their income plays a key role in national economies. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) warns that job losses will result in an estimated 20 per cent decrease in international remittances sent during 2020 (i.e. a reduction of around USD 110 billion). Central Asia and South Asia are likely to see the largest pandemic-related increases in extreme poverty in the world, resulting in a disproportionate increase in both female poverty and the gender poverty gap, particularly in South Asia. This decline in women’s status is also likely to result in a significant reversal in progress on women’s political representation.

4.2.2 Inclusion and social inequality

Vulnerable groups, including children, elderly, people with disabilities, refugees, LGBTQIA+ groups, migrants—including domestic migrants—and minorities, as well as indigenous peoples, have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic, which has exacerbated existing societal inequalities. Overall, across the region poverty levels and socio-economic inequalities have risen, sometimes sharply, as a result of the pandemic—the consequence of the combined effect of pandemic-related restrictions (e.g. lockdowns), and rising levels of unemployment. As described in a Global State of Democracy In Focus Special Brief. the pre-pandemic repression of the region’s ethnic and religious minorities, including ethnic Uighurs and Kazakhs in the Xinjian region of China and Rohingyas in Rakhine state in Myanmar, has been exacerbated during the pandemic and continues largely unchecked.

The position of migrant workers—and the remittances they bring—provides an important illustration of the way the pandemic’s economic impacts simultaneously mirror and magnify existing economic inequalities within the region. Several countries, such as Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Nepal, Pakistan, the Philippines and Sri Lanka, provide an important source of migrant labour for neighbouring states, including Middle Eastern countries and beyond. The remittances sent home, notably in Bangladesh, Nepal or the Philippines, were previously an important source of national income. In Nepal, for instance, remittances were 24 per cent of GDP in 2020. There are well-documented hardships that many migrant workers have faced while attempting to return home. Those who have managed to return via state-assisted repatriation schemes have mostly found themselves in economically challenging circumstances, with the disappearance of their remittances pushing both them and their dependents towards poverty.

Box 10. Covid-19 revealing poor conditions for Singapore’s migrant workers

Singapore’s economy is strongly dependent on an estimated 300,000 migrant workers who live in densely populated dormitories. Warnings of the likely consequences if the virus struck in such conditions were voiced from early on. In April 2020, the virus hit the dormitories with a vengeance, leading to a spike in the country’s pandemic-related infection, seriously tarnishing Singapore’s image as a Covid-19 success story.

The pandemic also intensified tensions between migrant groups and local communities. The Global Monitor of Covid-19’s Impact on Democracy and Human Rights recorded cases of various forms of discrimination against migrant populations in several countries across the region. In some cases, migrants have been blamed for the spread of the virus, as seen in Bangladesh, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Malaysia and Singapore. Migrants have also been excluded from social protection plans adopted to address the impact of Covid-19. In Japan, for instance, state subsidy payments are only available for those with residential status. In the Republic of Korea, undocumented migrants have been excluded from state-sponsored face mask distribution programmes and Malaysia’s vaccine programmes excluded migrants, refugees, stateless people and those in immigration detention centres.

Rise of ethnonationalism

Over the last decade, rising nationalism has led to the infusion of religion in politics in a number of countries, including India, Indonesia and Sri Lanka. Such tendencies contribute to the weakening of democracy by undermining pluralism, increasing societal polarization and, in the worst cases, heightening conflict. As per the GSoD Indices, India, Indonesia and Sri Lanka are registering their all-time lowest scores on Freedom of Religion since 1975.

Since the onset of the pandemic, several countries in which ethnonationalism and ethnic and religious fault lines were already at play have undergone a deepening polarization—as evident in, for example, the tensions around Muslim community burial rights in Sri Lanka. Particularly in South and South East Asia, this trend could further deepen the pandemic’s socio-economic impacts, intensifying latent or existing societal polarization. This dynamic was already witnessed in the social media-fuelled outbreaks of anti-minority hate speech engendered by pandemic ‘super spreader’ religious gatherings during the pandemic’s early stages in India and Sri Lanka.

Overall, there is a clear risk that, in the Asia and the Pacific region as elsewhere, economic crisis and growing inequalities stemming from the pandemic could help to usher in a new wave of nationalist-populist politics, carrying serious consequences for minority populations. While the 1997 Asian financial crisis had a positive effect on democratization in some countries (the Reformasi process in Indonesia, for example), the present crisis has the potential to increase the appeal of authoritarian rhetoric that gives pre-eminence to stability as the means to achieve economic development.

Box 11. Politics of othering—insidious driver of democratic backsliding

In recent years, the phenomenon of ethnonationalist mobilization, sometimes accompanied by a religious dimension, has been growing in both authoritarian and democratic countries across the world. In democracies, this is a cause for concern since it goes against the progressive trend of a deepening of universal citizenship and inclusive management of diversity along a number of lines (ethnic and religious included). Democracies aspire to give all their members not just the promise of equal constitutional rights but also the confidence to participate equally in the affairs of the polity. Ethnonationalist politics undermines this aspiration. It fragments the body politic into a ‘nationalist self’ and a ‘hostile other’, with the former presenting itself as the one who safeguards the essentialist idea of the nation as it has been or was destined to be, and the other as the one who challenges it.

These two groups of citizens emerge through a ‘politics of othering’ that is increasingly being deployed by political leaders and parties across the world, including in a pervasive way in Asia and the Pacific. The ‘politics of othering’ creates polarized qualities of the ‘self’ and ‘other’, in a sense of ‘virtuous self’ and a ‘villainous other’. If the self is nationalist, the other is anti-nationalist. If the self is a cultural insider, embodying the values of the home civilization, the other is a cultural outsider representing the values of an alien civilization. This politics of othering takes many forms but all of them fit the discourse of a nationalist self and a hostile other. In democracies, because of the need to create loyal and enduring voter support, this form of mobilization has gained political currency, offering considerable immediate benefit. It is the low-hanging fruit that parties seek to pluck since it plays to the prejudices and anxieties about the other within large sections of the population. This growing ‘politics of othering’ has contributed to democratic backsliding in the region, since it fragments the polity and promotes a sense of threat and vulnerability among some sections of society.

In autocracies and democracies alike, ethnonationalism is instrumentalized for nationalistic mobilization, where the nation is identified with certain cultural traits and lineages. This can be clearly seen in the politics of the People’s Republic of China, where the ethnic Han is pitted against the Uighur other. In Myanmar, it is the Buddhist self (describing most ethnic groups, as well as the historically dominant Bamar ethnic group) against the Muslim other, in particular the Rohingyas. In Viet Nam, it is the Vietnamese self against the Chinese other that periodically descends into violence against Chinese businesses. Similar tendencies can be seen in democracies around the region, such as India, Indonesia, Nepal, Sri Lanka and more. Ethnonationalist mobilization along self/other lines is increasingly being resorted to by political actors across the spectrum because of the demands of competitive politics.

Chapter 5. Checks on Government

The Checks on Government attribute aggregates scores from three subattributes: Effective Parliament, Judicial Independence and Media Integrity. It measures the extent to which the parliament oversees the executive, as well as whether the courts are independent, and whether media is diverse and critical of the government without being penalized for it.

Attacks on institutions central to the integrity of functioning democracies—including parliaments and other key independent institutions such as the judiciary and media—represented a significant challenge to democracy even prior to the pandemic. Over the five years leading up to 2020, the biggest decliners in Checks on Government are the Philippines, Sri Lanka and Cambodia, followed by Nepal, Viet Nam, Kyrgyzstan and India. The positive outliers are Uzbekistan, Thailand and the Republic of Korea, as well as Malaysia and Myanmar (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Worryingly, several democracies (India, the Philippines, Sri Lanka) have suffered decreases in all of the subattributes (Effective Parliament, Judicial Independence, Media Integrity) of Checks on Government, as demonstrated in Figures 11, 12 and 13.

Figure 11.

Figure 12.

Figure 13.

Box 12. Executive aggrandizement in India

As argued by Tharunab Khaitan, the executive aggrandizement in India has taken place through multiple, small-scale yet systemic assaults. These incremental changes have affected accountability along vertical (electoral), horizontal (judiciary and fourth-branch institutions) and diagonal planes (media, academia, civil society), arguably by reducing the effectiveness of these institutions in exercising executive oversight. The GSoD Indices confirm Khaitan’s findings. Erosion in the separation of powers is demonstrated through the non-appointment of the leader of the opposition after the 2014 elections, ignoring the veto power of the upper house, non-fulfilment of vacancies in fourth-branch institutions, and a list of attacks against media, academia and civil society actors. These occurrences are reflected in the consistent decline of democratic performance in India, including in Fundamental Rights and Checks on Government over the last seven years. It is particularly worrying that consistently high scores previously on Clean Elections have declined over the last two years.

In addition, the official pandemic response across the region has relied heavily on the role of security forces in many parts of the region. This phenomenon has two major impacts: an increased role for the military and police forces in what is in fact a public health emergency; and policies that distance or effectively remove the military from civilian and legislative oversight. Overall, there is a strong likelihood of the military’s increased role outlasting the pandemic itself.

The political role played by the military partly explains the continuing democratic fragility that characterizes some countries in the region (Bangladesh, Fiji, Myanmar, Pakistan and Thailand). In all these countries, historically, military forces have played a pivotal role in politics, either as elected or unelected members of the legislature and controllers of government ministries and authorities (Myanmar and Thailand) or by alternately endorsing and/or withdrawing support for elected civilian authorities (Bangladesh and Pakistan). This dynamic has served to inhibit both popular control and political equality. In some countries, moreover, this role is echoed in the more recent appointments—by civilian governments—of senior military figures, both active and retired, as leading figures in impromptu pandemic response structures (Indonesia, Philippines, Sri Lanka), often with large public support.

Parliaments across the Asia and the Pacific region have been severely disrupted by the pandemic. A trend that can be observed across the region has been the shifting of decision-making power to the executive—at least temporarily—with a potential weakening of parliamentary powers and oversight. Related challenges—including limited parliamentary oversight of pandemic spending, and the executive at times using the pandemic as an opportunity to push through legislation that would not have otherwise passed parliamentary scrutiny—have been observed during the pandemic. In the Philippines, the parliament passed a law giving the executive extended powers for a limited time, aimed at implementing policies related to the state of emergency.

In 2020, Japan, Kyrgyzstan, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Sri Lanka and Viet Nam show the biggest drops in comparison with the year before in Effective Parliament, which are accounted for, partly, by the effect of the pandemic. In a longer perspective, looking at the last five years, the countries that have suffered significant declines in Effective Parliament are Afghanistan, Cambodia, Indonesia, Japan, Kyrgyzstan, the Philippines and Viet Nam. Taiwan, Thailand and Uzbekistan have recorded significant advances over the last five years.

5.1 INNOVATIVE PRACTICES STRENGTHENING PARLIAMENTARY FUNCTIONS

The pandemic has forced parliamentary innovation, in particular bringing day-to-day operations into the digital domain, in order for them to continue in the face of the health risks posed by the virus. In a number of legislatures, procedures were revised to protect parliamentarians and staff and streamline operations. Some parliaments have enabled proportionate attendance and voting according to party group size, so that activity can continue on a multiparty basis without crowded plenary and committee rooms. Different mechanisms have been used to achieve this result.

For example, in Australia, the system of ‘pairing’—where members from different parties who are unable to attend sessions agree to ‘cancel each other out’—was expanded to encourage its use and reduce the number of MPs in attendance. In New Zealand, a series of measures were enacted to reduce the need for physical presence: notices of motions can be submitted electronically, the number of permitted proxy votes has been increased, and oral and urgent questions can be submitted electronically rather than in person. Additionally, an innovation worth noting is the March 2020 establishment of a cross-party Epidemic Response Committee chaired by the leader of the opposition. The Committee was given plenary powers to inquire into the Government’s ongoing response to Covid-19, and in many respects, it became New Zealand’s ‘parliament in miniature’ during the lockdown. In Mongolia, a hybrid approach was adopted where the MPs were separated among five rooms in the parliament building, at safe distances from each other, with video connections between the different halls. New procedures were also enacted that allowed plenary and committee meetings to be held remotely through videoconferencing. Multiple countries, such as Indonesia and the Philippines, have made procedural changes to enable remote virtual sessions.

Figure 14.

The Covid-19 pandemic has inevitably highlighted the importance of future-proofing institutions for unexpected disruption. However, the unknown nature of some disasters and emergencies also means institutions ultimately need to be responsive and nimble—capable of implementing bespoke arrangements and processes suitable for the circumstances that arise. The success of the latter depends a lot on the institutional and political commitment to values of democracy, legitimacy and accountability. New Zealand’s executive and legislature were generally able to stay true to these values while pragmatically innovating civic processes, simultaneously delivering a strong response to the pandemic.

Dean R. Knight

However, in a number of countries across the world—including throughout Asia and the Pacific—the shift towards using digital means in parliamentary work has been slower. A total of 12 parliaments in the region suspended their sessions at some point during the pandemic, either for a specific period or indefinitely.

Some parliaments in the region, including Australia, Indonesia, New Zealand, Pakistan and the Philippines, established Covid-19 committees to monitor the government’s handling of the pandemic, reclaiming their primary oversight role. In some instances, however, the committees established have been the subject of criticism—as, for example, in Pakistan, where the opposition parties boycotted the meetings, citing bias by the Speaker.

5.2 JUDICIAL INDEPENDENCE

The region scored 0.46 on Judicial Independence in 2020, slightly below the world average (only Australia, New Zealand and the Republic of Korea saw high scores), and only a small improvement on 1975, when the region scored 0.39. In the five years preceding the pandemic, the Philippines, Sri Lanka and Viet Nam saw significant declines in Judicial Independence.

Alongside parliaments, courts often play a key role in constraining government action. The pandemic, however, saw the continuation of existing threats against judicial independence and also required the closure of many courts. Closures negatively impacted the ability of the judiciary to hold other actors to account and also limited access to justice, with at least 18 countries in the region experiencing constraints in the functioning of their court systems. To date, courts—including apex and lower courts—have played a range of roles in response to the emergency.

In Nepal, for example, the Supreme Court issued over 40 rulings against various pandemic-related measures between early 2020 and mid-2021, on issues related to the management of quarantine facilities, repatriation of migrant workers, and effective arrangements for importing oxygen and vaccines, among others. While several of these rulings remain unenforced, the Court’s willingness to play a role in reviewing the actions of other branches of government is a positive sign in a country that has transitioned from unitary Hindu monarchy to a federal, multiparty democracy over the span of a single decade (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

In some countries, the pandemic has been used by the executive to further undermine judicial independence. While it is difficult to know if such attempts would have been made independently of the pandemic, the issue needs to be watched closely. For example, in Sri Lanka, the 20th Amendment to the Constitution was passed in October 2020, resulting in a significant increase in presidential powers, including with respect to the appointment of government ministers and the composition of key parliamentary judicial and other review committees, and a weakening of both the legislature and judiciary’s oversight functions.

In order to slow the pandemic’s transmission, from March 2020, Singapore’s courts were instructed to hear only ‘essential and urgent matters’ and, as much as possible, by electronic communication. In practice, the majority of cases have since been conducted via Zoom. Reviewing the pandemic’s legal impact in January 2021, Chief Justice Menon further suggested that, while a ‘circuit breaker’ implemented in June 2020 had resulted in over 2,000 hearing days being lost in State Courts alone, it had also expedited the introduction and use of technology within the courts.

Where independent courts enjoy significant legitimacy, they have significantly shaped governmental responses. In Taiwan, for example, previous Constitutional Court decisions provided a constraining framework for the Government’s actions. Notably, the Court’s Interpretation No.690 of 2011 required that the Communicable Disease Control Act 1944, substantially amended after the SARS outbreak in 2003, must provide a time limit for compulsory quarantine, and provide further detailed regulations and prompt remedies (including adequate compensation) for quarantined individuals.

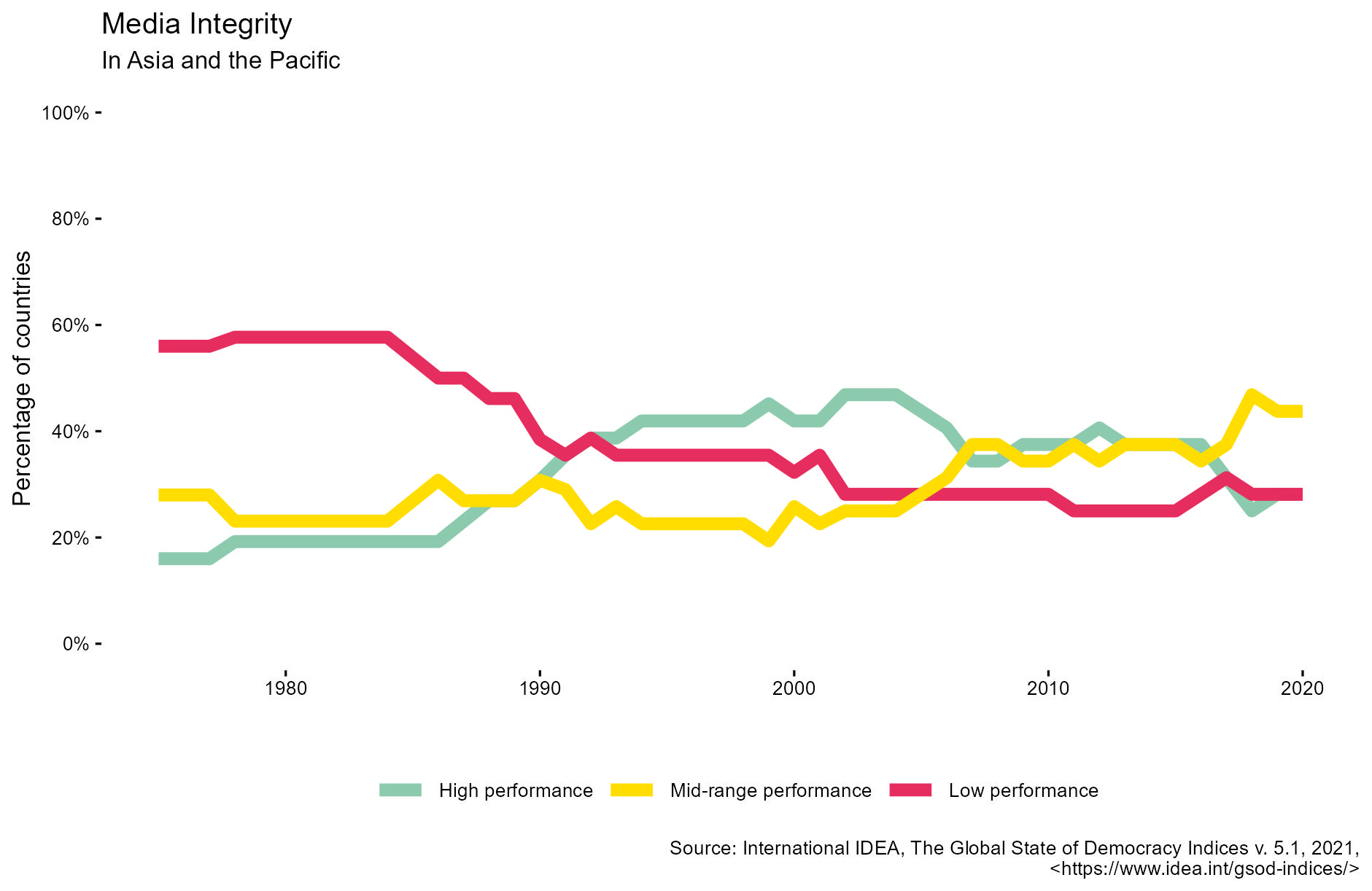

5.3 MEDIA INTEGRITY

One of the clearest examples of the pandemic’s magnifying effect on countries’ existing governance capacities relates to the media. In 2020, nine countries in the region had high levels of Media Integrity, with Australia, Japan, New Zealand and the Republic of Korea among the top 25 per cent in the world, while nine countries had low levels (all of them authoritarian regimes) (Figure 16). Countries that have suffered significant declines in Media Integrity over the last five years include: Mongolia, Pakistan, the Philippines, Sri Lanka and Timor-Leste. On the other side, Malaysia, Myanmar (up until the coup of 2021), the Republic of Korea and Uzbekistan saw notable improvements in Media Integrity over the last five years.

Figure 16.

Nepal, for example, has experienced a notable increase in harassment of journalists. In April 2020, Nepal’s Press Council shut down 17 online news portals for allegedly publishing disinformation related to Covid-19. In Hong Kong, the daily newspaper Apple Daily, which has been openly promoting democracy in Hong Kong, closed permanently in June 2021, as a result of the Hong Kong Government confiscating its assets. In the Philippines, having clashed publicly with President Rodrigo Duterte over a draconian new security law passed in mid-March 2020, veteran journalist and Rappler CEO Maria Ressa was found guilty of ‘cyber-libel’ for a story published in 2012, before the relevant legislation had even been passed. In Malaysia, the journalists involved in producing an Al-Jazeera documentary, broadcast in July 2020, were questioned by officials and subjected to sustained online abuse, including death threats.

Additionally, the pandemic’s impact extends beyond attacks on media freedom and integrity. In Australia, for example—as indeed elsewhere—the financial pressures intensified by Covid-19 have led to a large number of media closures, especially at the local level, resulting in what some analysts are describing as the emergence of ‘media deserts’.

On a more positive note, recognizing that, for many people, ‘media’ essentially means ‘online’ news and reporting, some responsive, tech-savvy governments such as Taiwan have focused very clearly on addressing online fake news about the pandemic and related issues. They appear to have done so with some success, an achievement doubtless explained in part by the fact that, early in the pandemic, all government departments were given the responsibility of responding to online disinformation by providing a ‘2-2-2’ ‘memetic’ (meme-based) response: a response within 20 minutes, in 200 words or less, and containing two images.

Box 13. Digital disruptions

A central feature of today’s world is the surging technological—in particular, data-driven—developments that increasingly shape and define contemporary societies. In the Asia and the Pacific region as elsewhere, the harvesting and marketing of data is restructuring the economy, while wider information and communication technology (ICT) and related advances continue to pave the way for major advances in areas from medicine and neuroscience to urban planning and environmental protection. No less importantly, for ordinary citizens across the region, data-driven technological advances continue to open extraordinary new communications possibilities, which from a democracy perspective bring with them critical new instruments for improving transparency and accountability. Notably, autocrats can no longer count on their repressive activities remaining out of the public spotlight—a fact underlined by the global media exposure of China’s continuing and allegedly genocidal assault on its Uighur minority.

Digital life’s centrality to contemporary struggles for democracy has been clearly demonstrated in the aftermath of Myanmar’s 1 February 2021 military coup. Three days after the coup the authorities ordered all telecom operators and Internet service providers (ISPs) to block the country’s most popular social media—Facebook, followed by Twitter and Instagram—citing the need to ensure national ‘stability’: unwitting testimony, perhaps, to the Internet’s central role in the continuing struggle for hearts and minds in Myanmar. Following this move, demand for virtual private network (VPN) services, which allow users to bypass online blocks, soared, with free proxy service Psion, for example, reportedly registering a surge in national demand from 5,000 users pre-coup to above 1.6 million by mid-February 2021. Responding to these post-coup developments, Facebook banned all pages relating to the Myanmar military, followed shortly after by a YouTube decision to remove five army-run channels from the service. Facebook has also officially recognized the democratic underground National Unity Government and continues to be the primary platform for information for many Myanmar citizens.

The trajectory of continuing global ‘digital disruptions’, then, is hardly all sweetness and light. Beyond online crackdowns of the kind in evidence in Myanmar, the most obvious downside of data-driven change is the emergence of powerful new mechanisms of control and manipulation, as evidenced in the inexorable rise of everything from powerful surveillance technologies to ‘fake news’, online bots and trolls, and unregulated contact tracing. All these phenomena are in plentiful evidence in democracies (and equally, or more so, in non-democracies) across the Asia and the Pacific region, bringing with them new challenges to just about every aspect of public (and private) life—institutions, legal frameworks, media practices and accountability frameworks included.

Chapter 6. Impartial Administration

Impartial Administration is the aggregation of two subattributes: Absence of Corruption and Predictable Enforcement. It measures the extent to which the state is free from corruption, and whether the enforcement of public authority is predictable.

While the regional average of Impartial Administration, including Absence of Corruption, has remained relatively stable, it is still below world average. Over the last five years, the biggest decliners in the subattributes in the region are Cambodia, followed by Sri Lanka and Indonesia (Figure 17). The biggest continued gains have been seen in Uzbekistan.

Figure 17.