Chad

Chad performs at low levels across all four categories in the Global State of Democracy’s framework, with scores in the bottom 25% of countries. Over the last five years (which included an unconstitutional change of government and a transitional election), Chad has experienced declines in all the factors of Representation and also in Judicial Independence. Although its economy was previously dependent on agriculture, the production of oil has grown since 2003 and today accounts for roughly 70 per cent of all exports and 15 per cent of the GDP. The country struggles with both a high poverty rate, and food insecurity – both of which have been affected by periods of extensive flooding and internal instability. Due to regional instability, Chad is also host to millions of refugees.

Chad was part of the Kanem-Bornu Empire until France imposed colonial rule between 1900 and 1960. France deployed soldiers to administer the Chadian colony, which was governed through violent force and stoked inter-communal divisions. The country’s post-independence history has been coloured by protracted conflict, including violent contests for political power, and enduring ethnic and religious tension between the animist and Christian south and the Muslim north. Political and insurrectionist dissent has been driven by the competition over oil revenues, corruption, ethnic politics, and state oppression – and has been continuously marked by shifting allegiances and familial and tribal relations within the political elite. The Déby family has ruled Chad for almost half of its post-independence history.

Instability is the foremost obstacle to democratization. Major insurgent groups reject a peace agreement forged between Chad’s government and 30 rebel and opposition groups. Additionally, unresolved inter-ethnic conflict, fuelled by former President Idriss Déby’s preferential treatment of his own Zaghawa ethnic group, continues to be a problem. Climate change-related natural disasters have worsened resource-driven intercommunal conflict. The proliferation of arms throughout Chad and its insecure borders, some of which are sites of violent conflict in other countries, contribute to local-level conflict. Furthermore, Boko Haram has established bases throughout the Lake Chad Basin area, resulting in clashes between Chadian forces and the insurgents.

Chad is among the world’s bottom 25 per cent of countries with regard to Gender Equality. It has among the world’s highest rates of child marriage, and female genital mutilation is a widespread practice. Gender inequality in Chad can be attributed to challenges unique to the Sahel region, including climate change, food insecurity, poverty, political instability, violent extremism, and conflict.

Despite representing a return to civilian rule after three years of military government, the violent and repressive chain of actions in the lead up to the recent presidential election suggest that both Representation and Participation should be monitored in the near-term; the 2024 electoral period was marked by political violence, including the fatal shooting of a key opposition candidate, and irregularities in the voting process. The constitutional referendum of late 2023, likewise offers little promise for progress – it has been frequently criticized for its lack of inclusiveness and failure to consider key concerns of the opposition. Consequently, the situation in post-elections Chad remains highly fragile, and further instability may have far-reaching impact across all core indicators of democratic performance. Beyond its internal dynamics, Chad is additionally vulnerable to conflict developments in its neighbouring countries. Therefore, the worsening of the Boko Haram conflict in Nigeria, clashes in Cameroon, and unrest in Sudan’s Darfur region may result in increased refugees, which could contribute to worsening intercommunal conflicts over limited resources.

Last updated: July 2024

https://www.idea.int/democracytracker/

October 2024

Chad imposes new media restrictions ahead of December elections

On 9 October, the president of Chad’s media regulator, the High Authority for Media and Broadcasting (La Haute Autorité des Médias et de l’Audiovisuel, HAMA), Abderamane Barka, announced a directive prohibiting private media from publishing online audio-visual content outside of narrowly defined circumstances. Barka said outlets that violated these regulations would be suspended or have their licenses revoked. He added that outlets had to employ professional journalists with official press ID cards. The measures were presented as being part of a ‘cleaning up of the media landscape’ ahead of the legislative elections scheduled for 29 December. On 4 October, HAMA suspended Le Visionnaire newspaper over an article it published on alleged government corruption and suspended two senior members of its staff because they did not have press identity cards. The Committee to Protect Journalists, an NGO, accused the Chadian authorities of ‘using press accreditation as an instrument of censorship.’

Sources: La Haute Autorité des Médias et de l’Audiovisuel, Jeune Afrique, Committee to Protect Journalists (1), Committee to Protect Journalists (2), Tchadinfos

September 2024

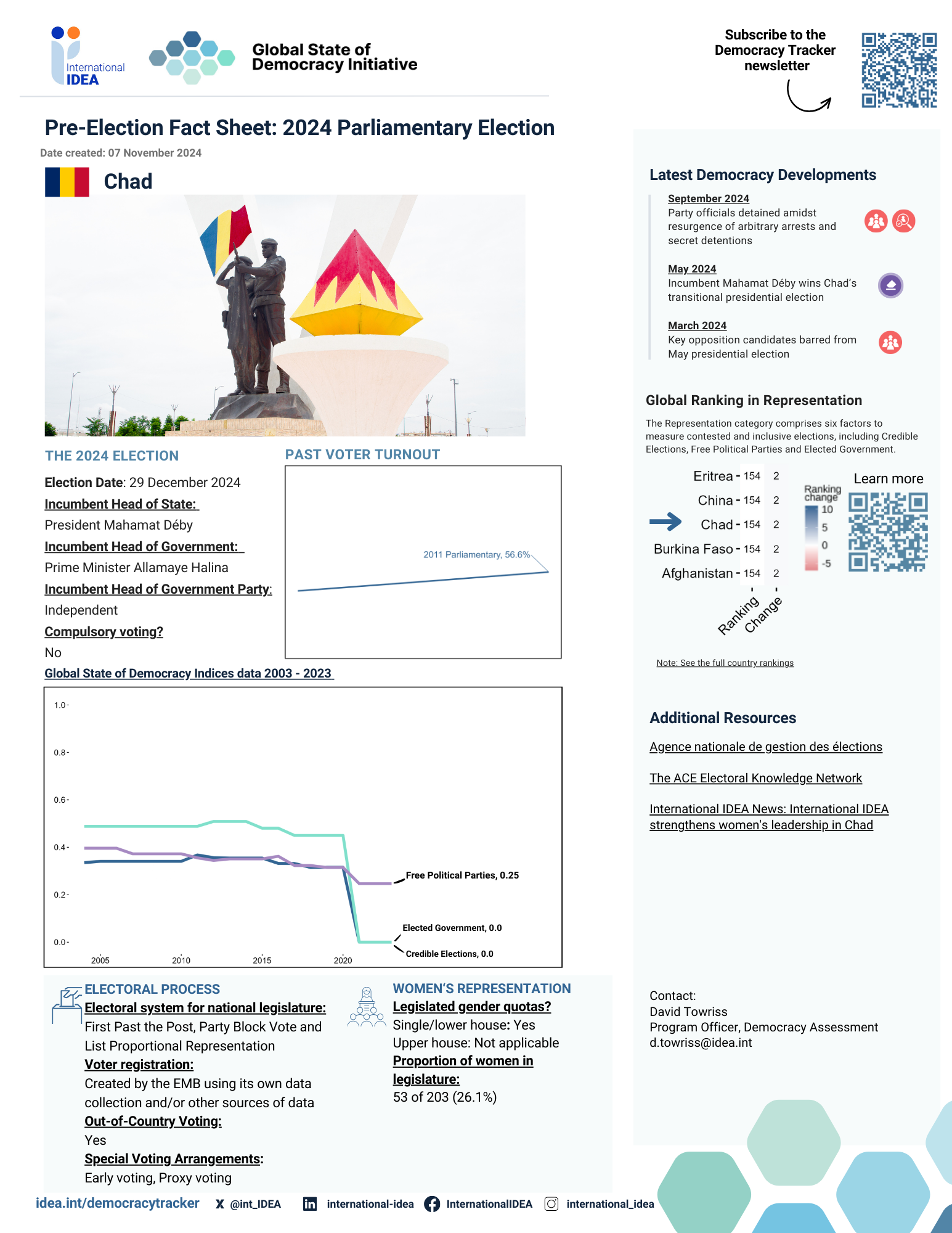

Party officials detained amidst resurgence of arbitrary arrests and secret detentions

In September, prominent officials from the ruling Patriotic Salvation Movement (Mouvement Patriotique du Salut, MPS), and the opposition Socialist Party Without Borders (Parti Socialiste Sans Frontières, PSF) were reportedly detained by Chad’s intelligence services, as part of a broader pattern of arrests. According to the PSF, Robert Gam, the party’s Secretary-General, was ‘kidnapped’ on 20 September, having been subjected to ‘harassment and intimidation’ by authorities since the killing of the party’s leader Yaya Dillo in February 2024. Days earlier, Gam had threatened protests over the ongoing detention of several of Dillo’s associates. Allah Ridy Koné, an executive of the MPS, was arrested by security forces on 28 September. The reasons for the arrests remained unclear at the end of September, but according to the World Organisation Against Torture, they coincided with a ‘resurgence of arbitrary arrests and secret detentions by the intelligence services in Chad’.

Sources: Jeune Afrique, Radio France Internationale, International Crisis Group, International IDEA, World Organisation Against Torture

May 2024

Incumbent Mahamat Déby wins Chad’s transitional presidential election

On 6 May, Chad held presidential elections that formally ended the three-year rule of the country’s transitional military government. Former interim president, Mahamat Déby, of the Patriotic Salvation Movement (Mouvement Patriotique du Salut, MPS) won the election in the first round, receiving 61.03 per cent of the vote, according to official results declared by Chad’s election agency, the Agence nationale de gestion des élections (ANGE) and confirmed by the Constitutional Council (le Conseil constitutionnel). Prime Minister Succès Masra, of Les Transformateurs came in second place with 18.54 per cent. The election was contested by ten candidates, only one of whom, Lydie Beassemda, is a woman. Voter turnout was reported to be 75.89 per cent of registered voters. The election results were unsuccessfully challenged in the Constitutional Council by Masra, who alleged irregularities, including ballot stuffing. Two thousand nine hundred civil society members trained by the European Union were denied accreditation to observe the election by the ANGE , but it was observed by international observers from the Economic Community of West African States and the Community of Sahel-Saharan States, which declared it to have been free and fair.

Sources: Jeune Afrique (1), Jeune Afrique (2), Voice of America, International IDEA, The Conversation, Tchad Infos

March 2024

Key opposition candidates barred from May presidential election

On 24 March, Chad’s Constitutional Council announced that 10 of the 20 candidates for the forthcoming presidential election in May had been barred due to ‘irregularities’ in their applications. Amongst the excluded candidates were two outspoken critics of the government, Nasour Ibrahim Neguy Koursami and Rakhis Ahmat Saleh, the former of which is reported to be the subject of a preliminary criminal investigation by the Constitutional Council for suspected forgery in relation to his application. According to ISS Africa, a research institute, the law applied by the Council to exclude Koursami and another candidate, Clément Bagaou, was obsolete. The candidates approved to compete in the election were regarded by analysts, diplomats and the political opposition as offering little serious challenge to incumbent, Interim President Mahamat Idriss Déby Into. The barring of opposition candidates follows the death in February 2024 of leading opposition figure, Yaya Dillo Djerou, during an army assault.

Sources: Jeune Afrique (1), Jeune Afrique (2), Al Jazeera, Voice of America, ISS Africa

See all event reports for this country

Global ranking per category of democratic performance in 2023

Basic Information

Human Rights Treaties

Performance by category over the last 6 months

Election factsheets

Global State of Democracy Indices

Hover over the trend lines to see the exact data points across the years

Factors of Democratic Performance Over Time

Use the slider below to see how democratic performance has changed over time