The Information Environment Around Elections

By Ingrid Bicu

About the project

Background

While digital content consumption has increased significantly and more people turn to the Internet to search for information, including on politics and elections, the information environment around elections is an under-researched area. To benefit from its features with a minimum of risks, it is essential for all the stakeholders involved in elections to have a clear understanding of its dynamics and be aware of its positive and negative potential and impact.

International IDEA has worked on the topic on multiple levels, globally, regionally, locally, and from various angles. However, in the process of tailoring our support for the boundary partners, we noticed that while some challenges were generally listed by stakeholders, the information environment around elections was insufficiently mapped out to provide a proper understanding of the issues and inform interventions. Moreover, it was repeatedly acknowledged by the practitioners’ community that more comprehensive research is needed to identify the vulnerabilities and risks in the information environment around elections, to inform suitable, context-adapted actions.

Hence, International IDEA initiated a series of parallel global research projects as part of a comprehensive exercise of mapping the information environment around elections and identifying the way it impacts individuals and groups - with an important gender angle - processes and organizations in the field of electoral management. We adopted a cyclical approach to keep up with the accelerated dynamics of the environment we were studying and generate actionable insights. The results aim at informing recommendations and guiding interventions to prevent and mitigate the impact of malign practices in this area.

Definitions

The information environment around elections encompasses the elements of the global information environment, a dynamic aggregator of human and non-human actors and systems that generate, are exposed to, use content, or serve as platforms for content dissemination, collection, processing, analysis and decision making based on it.

The particularities are associated with the roles the users acquire as part of the electoral processes – as, for example, voters, electoral officials, electoral management bodies (EMBs), and political competitors - and the ultimate stake: trusted elections and accepted electoral results.

This global research maps and analyses the malign practices in the online information space and their impact on individuals, processes, and organizations in the field of electoral management and aims to inform the policies, actions, and measures to support the resilience of electoral officials and institutions in general, and of women and vulnerable and historically marginalized segments in particular.

We consider malign practices in the information environment around elections the generation and/or manipulation of content in a way that has the potential of negatively impacting the management and organization of elections, whether we speak about individuals in their different, many times overlapping roles across the electoral cycle, electoral processes and organizations, leading to distrust, non-acceptance of electoral outcomes and eventually violence.

For the purpose of this research, disinformation targeting elections, whether we refer to processes, organizations, or individuals is defined as the false or misleading content deliberately generated and spread to influence the audience and generate negative attitudes and behaviors related to the conduct of elections and the electoral outcome.

We acknowledge the possibility that false information can be generated and spread without ill intentions (misinformation), as well as the circumstances when disinformation turns into misinformation across the dissemination flow. We consider these, along with malinformation (accurate information spread with the purpose of causing harm), as well as other forms of aggression and harassment in the information space, harmful in effect, thus subsumed to the malign practices in the information environment around elections, as defined above.

Malign euphemistic content refers to intentionally disguised offensive material, covering disinformation, abusive, defamatory, obscene, threatening, and violent intentions, among others, in text or multimedia formats. This type of content is used by ill-intended actors in the information environment to achieve the harmful effect such as spreading disinformation, inciting hatred or violence, or damaging someone's reputation, while avoiding detection by online platforms’ algorithms and fact-checkers.

Ephemeral content refers to digital material, mainly photo and video, shared on some social media platforms, that disappears automatically after a certain period of time. The content can be customized to include elements such as text, GIFs, timestamps, and music, depending on the platform. Examples include Instagram and Facebook "Stories" and Snapchat, Facebook and Instagram "Live Videos". Due to their temporary nature, such posts can include harmful content that may evade content moderation and fact-checking filters.

Methodology overview

The electoral cycle was used as a reference to determine the proportion of disinformation attacks targeting each electoral process and the phase of the electoral cycle when the attacks were launched.

Evidence base research

International IDEA commissioned several fact-checking organizations and independent researchers to conduct comprehensive research on the cases of disinformation in the online space, targeting national elections in 53 countries across all continents between 2016 and 2021. For 17 of the 53 countries, data was also collected for 2022. The information environment around elections was mapped in 17 countries in Africa and West Asia, nine in Asia and the Pacific, 17 in Europe, and 10 in The Americas. A total number of 935 cases of disinformation targeting national electoral events were documented between 2016 - 2022.

The objective of this research is to establish a living comparative evidence-base with cases of disinformation and problematic content with the potential of influencing the perception on national/general elections through targeting individuals (electoral officials or providing support to the EMBs), electoral processes and organizations (EMBs or those providing support to the EMBs), identified in the EMBs online disinformation registers, national fact-checking databases, online media and specialized reports.

The research involved in the initial phase identifying whether the EMBs were holding public fact-checking registers and documenting the cases of disinformation identified in these databases, according to the methodology developed by International IDEA. Subsequently, the researchers mapped the national fact-checkers covering election-related topics and looked into their databases for cases of disinformation targeting elections.

Case studies

To ensure an in-depth understanding of the local context and its impact on the information environment around elections, International IDEA commissioned researchers to develop brief case studies for the 53 countries they have been researching.

Online survey

Two hundred twenty-nine electoral officials in 73 countries worldwide answered an online survey conducted by International IDEA between February 2022 and February 2023 on whether they have been targeted by disinformation and other types of online aggression and harassment while in their official positions.

Interviews

International IDEA experts and commissioned researchers interviewed approximately 30 current and former electoral officials from all regions of the world. They were selected based on two separate criteria: they confirmed having been targeted by disinformation and other types of harmful practices while in their official positions, as well as the availability for being interviewed, or they could contribute with useful information to the mapping exercise.

Workshop

Twenty-three current and former chairs and members of EMBs shared their lived experiences with disinformation, aggression and harassment in the information space in a closed-door in-person roundtable discussion organized by International IDEA in Stockholm, in November 2022.

Social media analysis

To further complement the mapping initiative and ensure a better understanding of EMBs’ use of social media platforms, but also the impact they generate online, International IDEA commissioned a social media (mainly Meta/Facebook) analysis of 106 out of the 137 independent EMBs across the world, between 2016 and 2021. The selection was based on online presence and data availability. Only independent EMBs were selected due to the difficulty in separating the elections related content from the other type of content for governmental EMBs.

Stay tuned! More knowledge resources will be published soon.

Acknowledgements

This project was led by Ingrid Bicu and benefited greatly from the constant guidance and input from Therese Pearce Laanela and Peter Wolf.

It was conceptualized and implemented by International IDEA’s Electoral Processes Team, with substantive contributions from AfricaCheck, Arab Women Media Center (AWMC), Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN), MEMO98, National Citizens' Movement for Free Elections (NAMFREL), Anass Bendrif, Jose Luis Peñarredonda, Rafael Morales.

We are particularly grateful to the electoral officials who answered the surveys and participated in interviews and the workshop.

Many thanks to:

- Abdurashid Solijonov for the data analysis

- Cătălin Clonaru for the video and graphic design,

- Hyowon Park for the research and fact-checking,

- International IDEA’s Regional Europe, Africa and West Asia, Americas, and Asia and the Pacific programmes for their support in organizing the workshop and their inputs on the regional analysis

- Communications and Knowledge Management Team for their valuable guidance and support in disseminating the knowledge resources subsumed to this project

- International IDEA's Communications and Knowledge Management Team for their valuable guidance and support in disseminating the knowledge resources subsumed to this project

The resources draw on data and information from:

- International IDEA’s global evidence base research conducted between December 2021 - December 2022

- International IDEA’s online survey on disinformation and other types of aggression and harassment against electoral officials, conducted between February 2022 - February 2023

- International IDEA’s interviews with electoral officials in high visibility roles, conducted between February 2022 - February 2023

- International IDEA’s Electoral Management Design Database

- International IDEA’s GSoD Indices

- MEMO98 social media analysis, commissioned by International IDEA

Disclaimer: Due to limited data availability, the gender disaggregation, measurement and analysis across the data and knowledge products subsumed to this project are limited to women and men. However, in the methodology and survey developed by International IDEA, the respondents had the possibility to choose whether and how to report their gender identity.

Context

As part of the overall democratic backsliding, countries around the world increasingly experience attempts to undermine trust in elections (International IDEA GSoD Report 2021). The strategies involve exploiting vulnerabilities in critical areas, such as political, economic, or social, to influence the population’s perception and undermine trust in key democratic institutions such as electoral management bodies (EMBs). The information space poses increasingly challenging issues, with isolated mis- or disinformation incidents or concerted influence operations having serious disruptive potential. Disinformation, misinformation and malinformation have the potential to target not only individuals and groups but also processes, organizations, and even countries.

Disinformation targeting organizations, processes and individuals in the field of electoral management, as well as various forms of aggression and harassment in the information environment, are global phenomena and pose a serious threat to democracy. Attacks in the information space, often spread online, against electoral processes, institutions or organizations providing support to EMBs, and electoral officials with a public profile may also lead to or exacerbate violence and conflicts (International IDEA 2020).

Online platforms play an essential role: the inexistence of spatial and temporal barriers, the (perception of) impunity conferred by the lack of, limited or ineffective oversight and prosecution, anonymization, microtargeting, inauthentic behavior, and other features of social media platforms enable harmful actors to engage users in confrontations they don’t necessarily understand, and without artificial stimulation they would probably not even be part of. This results in increased polarization, which has been correlated in multiple cases to democratic erosion. The impact can go as far as changing the faith of nations and potentially affecting the world order.

The need for electoral institutions and other electoral actors to develop effective, evidence-based strategies and responses to these online challenges is acute.

REPORT: THE ONLINE INFORMATION ENVIRONMENT AROUND ELECTIONS

Global analysis of disinformation targeting electoral processes, organizations and individuals in electoral management between 2016 – 2022

What is the trend?

The trend is upward

Figure 1: The global evolution of the cases of disinformation targeting elections between 2016 – 2021

Data for at least 101 national electoral events in 53 countries, out of which only four reported no case of disinformation targeting elections during the researched period. Data for 2022 was excluded from this trend analysis because it was available only for 17 countries.

Cases of disinformation against elections (processes, organizations, individuals supporting the management of the processes) were identified in 92% of the 53 countries across the globe mapped by International IDEA’s research.

The global evolution of cases between 2016 – 2021 reveals an ascending trend, with disinformation attacks peaking during the electoral years.

The highest number of disinformation cases in all 53 countries was registered in 2019. Data for 2022 is partial and only covers 17 countries. It still totalizes 71% of the number of cases identified in 2019. This might indicate record-high numbers of attacks for 2022.

Who are the targets?

Legislative elections are slightly more targeted, compared to other types of elections

Figure 2: Which type of elections were the claims related to?

The cases of disinformation are divided relatively evenly between all types of national periodical elections. However, legislative elections emerged as the most targeted.

Data for referenda represents 4% of the total number of cases and refers to six countries with one such electoral event each, during the researched period. This indicates that when they happen, referenda are similarly targeted by disinformation as the other types of elections.

Disinformation targets electoral processes and organizations in parallel

Specific processes of the electoral cycle were targeted in 95% of the cases documented, the great majority in parallel to attacks against the electoral management body (EMB).

Figure 3: Which organizations were targeted by disinformation?

EMBs, especially the ones in mid-performing democracies, were targeted by disinformation in 94% of the attacks against organizations.

Private companies providing services to EMBs were targeted in 2.4% of the disinformation attacks.

International organizations and election observation missions were targeted in 1.9% of the cases.

Disguise techniques are used to hide attacks against individuals in electoral management

The strategies used to spread harmful content in the information space around elections vary, and attacks don’t focus on organizations and processes alone.

The evidence base research indicates that individuals affiliated with elections were targeted in 15% of the cases reported online. Most of the individuals targeted are electoral officials in leading positions within EMBs. However, our complementary survey and interviews indicate that disinformation, along with other harmful online practices directed at electoral officials in high-visibility roles, has surged significantly.

Women experience an additional layer of disinformation, based on gender. It portrays them as incapable of fulfilling their duties and it is linked to societal stereotypes and misogyny. However, these attacks often escape content moderation and fact-checking scrutiny on platforms. They often go unreported due to disguise tactics, such as the use of malign euphemistic content, their format, or their short lifespan online. The spread of such content through ephemeral posts also evades platforms’ moderation and fact-checking filters.

While the immediate impact is discrediting the officials as professionals and individuals, in the majority of the cases we have mapped, these malign practices are part of broader strategies of undermining the credibility of the processes they manage and challenging the functional independence of the institutions they represent (EMBs). Beyond the highly damaging impact on an individual and institutional level, the phenomenon has severe implications for the democratic landscape in the countries where it has been observed, with global repercussions.

Representatives of international organizations and election observation missions were also targeted by disinformation, although at a lower scale. The attacks were frequently initiated or amplified by electoral competitors.

The topic is being addressed extensively in the upcoming report on the Challenges for electoral officials in the information environment around elections.

Democracies are more targeted by disinformation

The figure below depicts the relationship between regime type and the number of reported cases of disinformation targeting electoral management. It shows that democratic countries experience the highest number of cases on average. One possible explanation is that in authoritarian regimes, the government exercises strict control over the media and the flow of information, making it harder for disinformation to gain traction or even to be disseminated in the first place. It is also possible that cases of disinformation targeting elections in authoritarian regimes are less visible or documented due to restrictions on freedom of the press and other forms of censorship.

Figure 4: Average number of cases per country/regime type.

Hybrid regimes have twice the number of cases compared to authoritarian regimes.

The more democratic the societies, the higher the likelihood of greater diversity of sources of (dis)information.

However, further disaggregation of data into the three sub-categories of democracies shows that mid-range performing democracies experience the largest numbers of cases compared to the two other categories. This can be explained through the correlation between a more open information environment than the one in weak democracies, but less strong democratic institutions and a more polarized electorate compared to high performing democracies.

The high-performing democracies show a smaller number of cases than the mid-range ones. They generally have stronger institutions, more transparent political processes, and higher levels of digital literacy, making disinformation more difficult to gain traction.

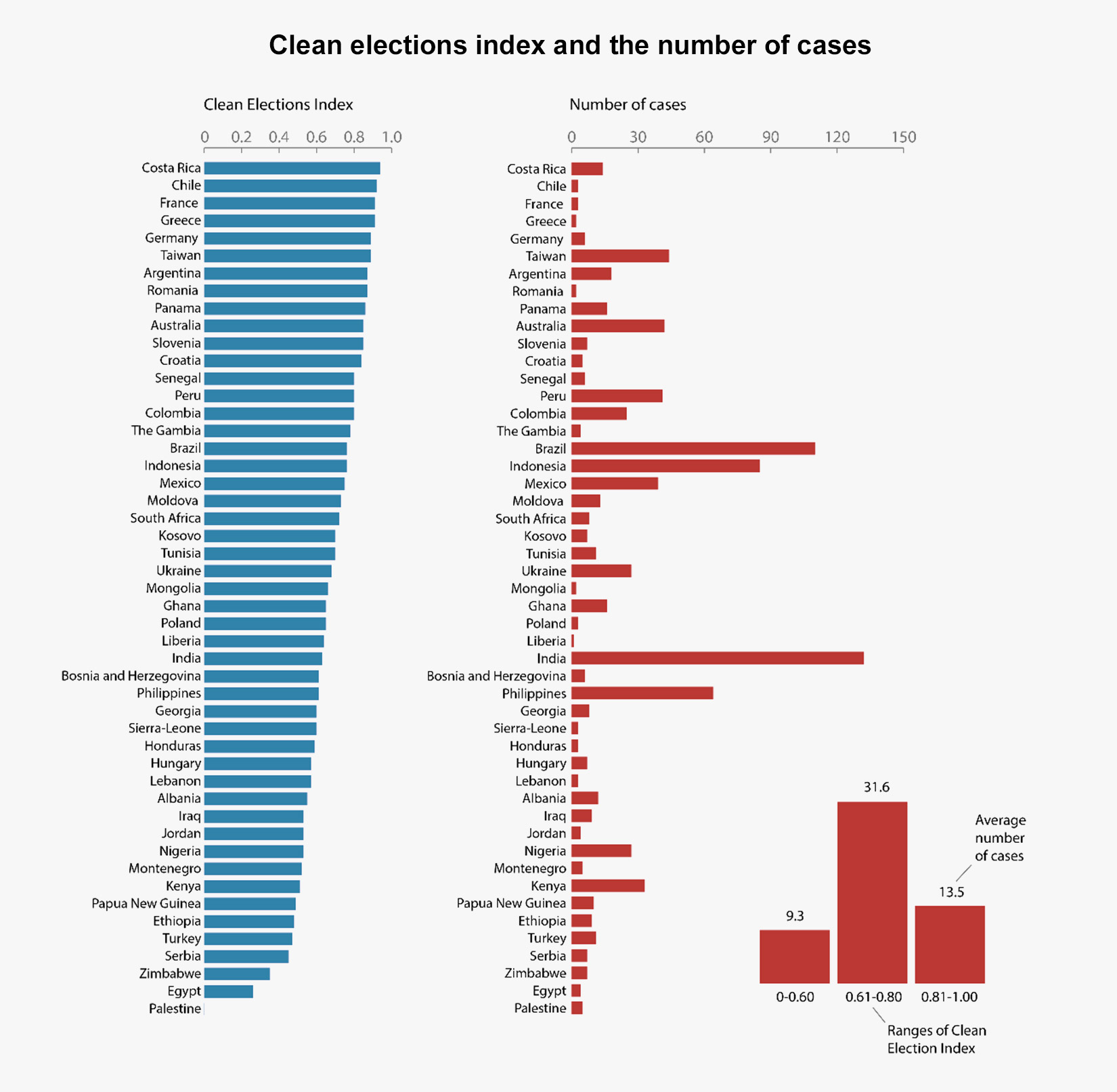

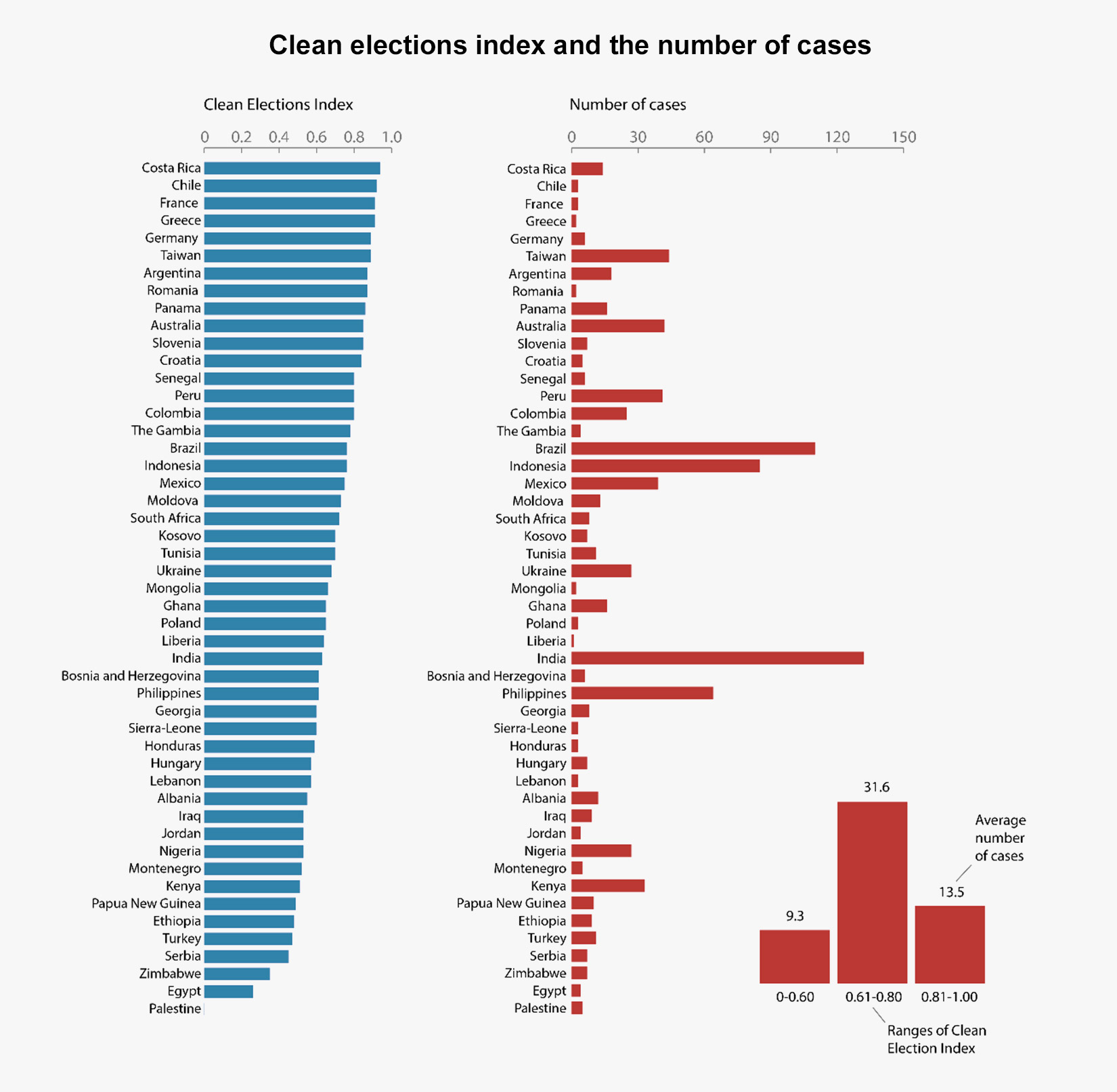

The countries at the top and the bottom of the Clean Elections Index experience much fewer cases, compared to the ones with average scores

The analysis of the data regarding Clean Elections, provided by International IDEA’s GSoD Indices against the number of reported cases suggests that the number of cases of disinformation targeting elections is higher in the areas with middle scores in the Clean Elections Index. This is also confirmed by horizontal bar chart which provides the average number of cases for each selected range of the Clean Elections Index. In the range of scores between 0.61 and 0.80, the average number of cases is highest (31.6) compared to the two other range groups.

The varying levels of trust in electoral management bodies could explain the distribution of disinformation cases. EMBs with a strong reputation for delivering elections at a high standard may have built a shield against disinformation attempts due to their repeated success and proven independence, deterring potential malign actors. Conversely, countries with weak EMBs may not be targeted as the level of trust is already low. Additionally, the research revealed that EMBs in high performing democracies are more involved in countering disinformation.

These are explanations based on global comparative data and the obvious exceptions confirm the need for a local and regional context assessment and analysis. The geopolitical context, media landscape, and social dynamics can play a significant role and should be taken into account when analyzing disinformation in specific countries and regions.

Figure 5: Analysis of the Clean Elections Index and the number o cases documented in each country

When are most of the attacks being launched?

Disinformation attacks are initiated across the entire electoral cycle, although unevenly

The evidence base reveals that most of the disinformation attacks are being launched during the electoral campaign (33%) and voting operations and elections day (24%). These are the times when public interest and attention to the electoral process are at their highest, making it easier for disinformation to spread rapidly and gain the highest reach.

Seventeen per cent of the cases were launched in the post-voting period, 11% in the planning and implementation phase, and 8% during the verification of results stage.

Figure 6: Processes targeted and disinformation attacks launched across the electoral cycle

What are the most targeted phases and processes?

The voting period is the most targeted phase of the electoral cycle

More than half (56%) of disinformation attacks against electoral processes target the voting period, including voting operations and elections day and verification of results. Special and external voting, as well as vote counting sum up 48% of the total disinformation cases targeting electoral processes.

Post-election activities were targeted in 10% of the cases and the planning phase in 11% of the total number of attacks documented. Eight per cent of all cases were related to the voter registration phase, including activities concerning parties and candidates.

How do the attacks unfold?

Malign actors use the period between elections to develop disinformation strategies

The observations made during the research suggest that many disinformation strategies are developed in advance through coordinated efforts between the initiators and the vectors of dissemination of the content. This indicates that disinformation campaigns are often carefully planned and executed, rather than being spontaneous or random acts.

Moreover, it seems that malign actors may engage in social listening during the period between elections, monitoring activities on social media platforms and other online spaces to learn more about trending topics and the perceptions and attitudes they generate among different groups of people. This allows them to develop and test potentially disruptive narratives, which can be launched and scaled up at opportune moments to maximize their reach and impact, as illustrated in the previous figure.

Disinformation and conspiracy theories meant to undermine public trust in elections emerged particularly in the period preceding elections and during the voting period, in relation to different electoral processes as well as organisations and individuals involved in electoral management. This is a critical time during the electoral process and disinformation attacks can have a significant impact on the (acceptance of) electoral outcome.

Phishing emerged as a threat related to voter registration on several occasions

Misleading information about where and when voters should register for elections, including links to cloned electoral management bodies' voter registration websites, with the assumed aim of gaining access to individuals’ personal data, was identified repeatedly during the research. Such attacks can lead to unintentional disenfranchisement, although it is difficult to establish the real scope, perpetrators, and intentions of these operations.

Who are the initiators?

Political figures and online media are among the main vectors of disinformation

Figure 7: Who were the initiators?

Although the initiators of disinformation in 69% of the cases are unspecified social media users, their profiles often reveal certain ideological or political views or provide indicators of being part of coordinated campaigns.

Domestic disinformation has emerged as an equally concerning phenomenon as foreign interference and is amplified by artificial social media algorithms and mainstream media.

In 17% of the documented cases, candidates or political figures are responsible for initiating attacks or spreading disinformation, while online media publications are responsible for 11% of cases. High-profile political and state actors, along with affiliated online media outlets, are among the main perpetrators of such attacks, generating confusion and distrust. It is often challenging to determine the "moral authors" of such attacks. Furthermore, it is concerning that foreign interference increasingly takes the form of financial support by foreign state actors for political parties and media outlets in targeted countries.

A profoundly damaging disinformation instance for electoral trust identified on a few occasions during the research is when attacks are being launched from within the EMB, especially the cases when these are initiated by high-level electoral officials. Obviously, when the EMB attempts to disinform the electorate on certain measures affecting the exercise of their electoral rights, it may cause serious doubts about the commitment of the electoral body to deliver fair and transparent elections.

Disinformation campaigns involving accounts linked to governmental employees or pages were documented in mid-range and low-performing democracies, as well as in hybrid regimes. In some cases, Meta/Facebook identified and suspended these accounts.

On much fewer occasions, NGOs/CSOs, religious organizations, and separatist groups were also identified as generators and disseminators of false or misleading content.

Foreign actors emerged as the obvious initiators in a limited number of cases.

Disclaimer: The research was able to identify the “apparent” initiators of disinformation. We recognize that deeper analysis is needed to establish whether connections exist with other domestic or external actors, as well as identify the unauthentic behavior.

Blurry line between disinformation and criticism

In some instances documented by the research, political figures and candidates, as well as civil society organizations claimed that measures by the EMBs lacked transparency, were politically biased or could have resulted in disenfranchising or scaling up voting possibilities for some categories of voters. In other cases, enhanced powers attributed to the EMB and electoral officials in high positions through rushed legal changes and removal of certain checks and balances and reducing oversight were also perceived as ways of undermining the independence and autonomy of the EMB and gaining political advantage.

While generating suspicions about the independence of the EMB, the questioning of such measures is part of the public oversight of EMBs activities and holds the institution accountable for its decisions.

What are the most used narratives?

Narratives focused on electoral processes

During the research, frequent cases of false or deceiving information on voting methods and conditions were documented, potentially leading to disenfranchisement. Examples include narratives such as “electoral IDs of people over 70 years old are being revoked” and notifications received by users of instant messaging apps regarding the invalidation of their identification cards. Incorrect information regarding certain electoral procedures and sanitary hygiene requirements for participation in the elections was also common.

Narratives falsely inducing the idea of rigging elections through different practices, such as unlawful manipulation of ballot papers, were trending, particularly during voting operations and election day. Claims such as “pre-marked ballot papers were discovered”, “ballot boxes were found filled with ballot papers”, “special pens will be used with an ink that can be erased and changed”, and “pencil marks are erased in the counting process” were meant to cast doubt over the fairness of the process and the accuracy of the results.

The implementation of new or scaling up existing voting arrangements, as well as other changes in the electoral processes or legal modifications, are instances particularly prone to disinformation attacks from malign actors. Recurring narratives relate to special voting arrangements (SVAs) such as mail voting, voting arrangements involving the use of technology, or voting from abroad.

| Electoral phase | Percentage of cases targeting the processes subsumed to the electoral phase | When were they initiated? | Who were the initiators? | What were the main narratives targeting each electoral phase? |

| Legal Framework | 0.2% |

|

|

Claims challenging the legitimacy of the electoral legislation |

| Planning and implementation | 11% |

|

|

Fraud with technology Political affiliation of electoral officials; corruption False information on upcoming election day and voting procedures |

| Training and education | 1% |

|

|

The EMBs failed to inform and educate the citizens on electoral procedures |

| Voter registration | 8% |

|

|

Unlawful manipulation of the voter register False or deceiving information regarding registration procedures and conditions Abusive disqualification of electoral competitors by the EMB. |

| Electoral campaign | 14% |

|

|

False or deceiving information on voting methods and conditions Claims of fraud through different methods: technology, unlawful manipulation of ballots, illegal mobilization of the electorate. Voting rights of migrants and refugees |

| Voting operations and election day | 48% |

|

|

Unlawful manipulation of ballot papers, including during the vote counting Rigged voting and counting technology, as well as EMB website manipulation, for manipulating the results of the election Enabling groups of people who don’t have the right to vote |

| Verification of results | 8% |

|

|

Vote counting fraud Release of false results Inadvertencies in the turnout reports |

| Post-election period | 10% |

|

|

Claims of fraud following purported investigations by electoral competitors. False results Inadvertencies in the turnout reports |

Table 1: Narratives focused on electoral processes. Compiled by the author using the evidence-base

Narratives focused on organizations

The great majority of the disinformation attacks against organizations target EMBs. Frequent false claims where the EMBs are accused of rigging elections and fraud through different methods, by abusing their prerogatives. Narratives on favouriting a certain electoral competitor while preventing candidates from running in elections, sometimes claiming non-compliance with certain legal requirements were documented.

The narratives the attacks against international organizations, including international election observation missions build upon are important to highlight: the topic of malign foreign interference in elections is being imported and directed against international organizations providing electoral assistance or monitoring the elections in those particular countries.

Private companies are being targeted with similar narratives. Other false claims include enabling electoral fraud through the technology they were providing.

| Type of organizations | Percentage of cases targeting the organization |

When were they initiated? (Electoral phase) |

Who were the initiators? | What were the main narratives? |

| EMBs | 94% |

|

|

Claims of fraud through different methods Favouriting a certain electoral competitor Preventing candidates from running in elections |

| Private companies | 2.4% |

|

|

Enabling electoral fraud through the technology they were providing. |

| International organizations | 1.9% |

|

|

Foreign interference in elections |

Table 2: Narratives focused on organizations in electoral management. Compiled by the author using the evidence-base

Narratives focused on individuals

The narratives against electoral officials focus mainly on political affiliation, favoring an electoral competitor and electoral fraud, and aim at undermining the credibility of the processes they manage and the institutions they represent (EMBs).

Representatives of international organizations and election observation missions were mainly targeted with claims mainly related to a lack of impartiality.

Similarly, representatives of private companies supporting the elections are being accused of serving the political agenda of certain candidates and committing electoral fraud through the technology they are providing.

| Individuals targeted | Gender | Percentage of cases targeting the individuals |

When were they initiated? (Electoral phase) |

Who were the initiators? | What were the main narratives? |

|

77% male 23% female |

15% |

|

|

Lack of impartiality Fraud Corruption |

Table 3: Narratives focused on individuals in electoral management. Compiled by the author using the evidence-base

What is the impact?

Distrust, the immediate impact of disinformation

Figure 8: The impact of disinformation on electoral officials, institutions and processes

The impact of the cases of disinformation documented is highly correlated with their reach. In the absence of resources to effectively measure the reach of the disinformation published and disseminated in the online information environment around elections, we developed our methodology in a way meant to reflect to some extent the level of reach: looking at the cases that made it to fact-checking databases, media or specialized reports implies a level of reach significant enough to potentially influence the perception related to the targeted subject.

After conducting extensive research and interviews, we have classified the impact of disinformation targeted towards electoral management on three levels: perception, attitude and behavior. These levels are linked to the three categories established: processes, organizations, and individuals involved in elections:

Perception

- alter the perception of the public related to the professional capacity, impartiality and transparency of EMBs, and electoral officials,

- cast doubts on the fairness of the electoral process and the correctness of the electoral results.

Attitude

- distrust,

- confusion on how and where people can exercise their electoral rights,

- non-acceptance of results.

Behavior

- electoral violence,

- intimidation, aggression and other types of malign behavior targeting electoral officials, resulting in loss of organizational knowledge and competence

- disenfranchisement,

- social division and unrest.

The analysis of the disinformation attacks and the voter turnout didn’t reveal any correlation between the number of cases and voter turnout. However, impact of disinformation on voter behavior is a complex matter, and may not be immediately evident. For example, while disinformation may not directly reduce voter turnout, it can still impact the perception and attitude of voters towards the electoral process, leading to long-term effects on participation in future elections.

Additionally, the impact of disinformation may not be evenly distributed across different segments of the voting population, and there may be variations in how different groups of people respond to disinformation. Therefore, it may be challenging to identify a clear correlation between the number of disinformation attacks and voter turnout based on the aggregated data.

What influences the dynamic in the information environment around elections?

Navigating the information environment around elections is hampered by poly-crises

In many instances, voters are faced with conflicting information about various aspects related to elections, particularly in overlapping crisis contexts. COVID-19-related disenfranchising claims and voting conditions for migrants or in contexts of instability and conflict are some of the instances where false rumors can have a significant impact on the electoral process.

False claims related to COVID-19 voting conditions, such as “voters would not be able to register without proof of vaccination”, or “elections were postponed due to COVID” repeatedly emerged during the research. Similarly, claims like “the EMB will not be conducting elections due to insecurity” or “migrants are being massively issued voting cards” are among the most frequent claims in areas of instability and conflict.

Disinformation/misinformation triggered by a lack of understanding or poor voter education

Dis and misinformation due to poor communication or insufficient understanding of different aspects related to elections and election procedures by different stakeholders, particularly when they involve changes, are important contexts that emphasize the essential role of strategic communication.

Electoral stakeholders are insufficiently prepared to deal with the challenges in the information environment

While this research is by no means exhaustive, the time, skills, and resources required for developing an evidence base proved that navigating this space is a challenge, even for skilled analysts and specialized organizations. It is even more unrealistic to expect voters to analytically process the overwhelming amount of information they are exposed to and critically evaluate the sources against their reliability and impartiality under the pressure of time and increasingly often fear generated by overlapping crises.

In this information environment where establishing what is true, false, or misleading is nearly impossible without solid critical thinking and media literacy skills, trust seems to be one of the main targets of the strategies aimed at undermining democratic institutions and delegitimizing electoral processes.

Hence, it is of critical importance that electoral management bodies (EMBs) consolidate a trust-based relationship with voters and other stakeholders and make sure they are regarded as a primary, reliable source of information on elections. This is highly correlated with their capacity to maintain their independence and deliver elections at the highest democratic standards.

Lack of punitive consequences encourages the increase of attacks in terms of number, complexity and aggressiveness

Malign campaigns around elections intensified and tended to be more complex and aggressive in the online space. This is presumably due to the perception of impunity considering the inefficient prosecution, encouraged by the anonymization possibilities for the perpetrators, as well as following the amplification algorithms of the platforms. As indicated by our research, in 69% of the cases, the initiators are unknown and legal action was initiated in only 1% of the cases.

However, it repeatedly emerged across the research that the offline space continues to play a significant role in the ill-intended campaigns. The study reveals that the two information spaces potentiate each other as part of disinformation and discreditation strategies. The number of online media sources initiating or disseminating false or misleading information indicates important issues related to the independence and impartiality of the media, as well as the quality of the journalistic act.

Ephemeral posts and malign euphemistic content elude detection

The limited timespan, as well as the prevalence of content in video and photo formats of the 24-hour “stories” on some social media platforms pose serious challenges for content moderation and fact-checking. Correlated to the high reach due to the “fear of missing out” behavior, these temporary (ephemeral posts) posts include disinformation and other types of harmful content and generate important damage to electoral management while remaining undiscovered.

Similarly, the disguised harmful content (malign euphemistic content) eludes the detection mechanisms by platforms and also tends to fall under the fact-ckeckers’ radar because of the difficulty of clearly fitting it into one of the categories subsumed to malign practices in the online environment.

What were the countermeasures?

The EMBs and fact-checkers complement each other

Our evidence base looked at concrete actions for specific cases of disinformation and the analysis reveals that 39% of the disinformation was debunked by the fact checkers and 38% through a statement made by the EMB. In 9% of the cases, both the EMB and fact-checkers debunked the claim. However, only 9 of 53 EMBs covered by this research maintain public debunking repositories. In 10% of the cases, no action was identified and in very few cases legal action was initiated. The complementarity in reaction between the EMBs and the fact-checkers revealed by the research indicates that civil society or media tends to fill gaps where the institutional reaction lacks. This prevents the informational voids around harmful content and points toward a potential whole of society reaction.

Figure 9: What were the countermeasures in the documented cases?

Broader research, including the interviews with electoral officials in leading positions, indicates that the measures EMBs took globally to address the issues negatively impacting elections in the information environment vary from none to leading collaborative networks with relevant actors and developing solid strategic communication.

Also, the EMBs are inclined to explore and address the impact of disinformation beyond their mandate. Such an approach is proving ineffective considering the wide range of targets and the significant differences in terms of impact and mitigation measures needed for combating the effects of disinformation and other malign practices in the information environment around elections for each category of targets.

However, such measures tend to be ad-hoc as the information environment around elections if often insufficiently mapped out on a national and global level to provide a proper understanding of effective interventions, suitable for the local context. Also, the roles and responsibilities of various actors remain unclear and different actors assume roles randomly.

EMBs implication in preventing electoral disinformation from achieving its objectives was influenced by factors such as unwillingness, lack of understanding of the issues due to the lack of media, especially digital media literacy among the EMBs leading officials, an institutional environment not oriented towards collaboration, limited mandate, lack of technical, financial, human resources and expertise.

The countermeasures initiated across the globe range from broad systematic changes such as the setup of new institutions, development of new regulations, and increased cooperation between existing institutions, to specific actions such as training programs for electoral officials and improved public communication and media literacy.

In some countries, a whole-of-society approach included enhancing interagency cooperation, establishing mechanisms of monitoring the digital space, collaborating with online and offline media and fact-checkers, training officials, developing strategies of (crisis) communication including within the network of collaborators to ensure consistency of the messages and avoid information voids, and raising the awareness among the population on the emerging challenges, as well as their way of manifestation.

Strategic communication structures or task forces established or pre-existing at the governmental level have issued guidelines to prevent the effects of dis- and misinformation, including those related to elections. These structures are interdisciplinary, either composed of experts from different areas, including elections or in close collaboration with the relevant actors. Some are treating disinformation, including the one targeting elections, as a matter of national security, with the involvement of security agencies. Regarding elections of critical infrastructure is another approach taken by several countries.

Abusive limitations to the freedom of expression and access to information were observed across the globe by state actors, under the pretext of tackling disinformation around elections In some cases, extreme measures have been implemented, including Internet shutdowns, network disruption or criminalizing disinformation was documented.

EMBs in high performing democracies are more involved in countering disinformation

The figure below shows how the implementation of the three most occurring measures differs in different levels of democracies. A correlation can be observed between the type of democracy and the measures implemented: the higher the level of democracy, the more likely that EMBs issue statements about the case, while the involvement of fact checkers and media are more common in lower performing democracies. Also, the weaker the countries in the level of democracy, the more chances are that no actions are taken about the case.

Figure 10: Analysis of the measures implemented by level of democracy

Conclusions

The lack of clarity related to the types of threats that manifest, as well as the roles and responsibilities for protecting elections in the information environment, can lead to the unfitted allocation of resources and ineffective strategies for prevention and protection. Measures should be focused on the impact, with clear delimitation of competencies and responsibilities in addressing the different types of malign practices that have the potential to affect trust in elections and the acceptance of the electoral outcome.

While most of the challenges apply globally, it is important to consider the regional and national contexts, including aspects related to mandates for protecting the information environment. A context-sensitive understanding of the independent and synchronized use of malign tools and tactics, mapping and assessing their risks, and potential impact on each area of vulnerability, is necessary to inform protection measures by competent actors.

Despite some ongoing regional initiatives, consensus on measures to discourage harmful practices online is yet to be achieved. Initiating coordination mechanisms between relevant stakeholders at the regional level, to ensure a consistent action plan across the region can prove effective.

The research revealed an organic, complementary reaction between EMBs and fact-checkers to disinformation targeting elections. While this speaks to the effectiveness of a whole-of-society approach, it is important to include other relevant actors as part of coordinated initiatives. An interdisciplinary, multi-stakeholder approach can provide a more comprehensive and effective response to malign attacks in the information space.

EMBs role and implication in preventing the effects of electoral disinformation is influenced by factors that range from mandate limitations, institutional capacity, organizational culture, to the level of understanding of the issues or even willingness to deal with such a complex phenomenon with sensitive implications. The role the EMB can play is highly correlated with the national context and perceptions vis-à-vis EMBs independence, impartiality and capacity to deliver on this regard. Any legislative change on this respect should be considered following consultations with the other stakeholders, including political parties, civil society organizations, the security sector, media etc.

Considering the limitations of EMBs in addressing the online challenges in the electoral field, establishing interagency collaboration mechanisms is highly necessary, as proven by International IDEA’s current and previous research. A dedicated national task force, bringing together the relevant agencies and stakeholders with expertise in different areas, could be an effective approach. Additionally, regular communication and information sharing among the different agencies can help to ensure a timely and effective response to emerging digital threats.

Despite the increasing recognition of strategic communication in building trust and addressing online information manipulation threats, we observed a lack of readiness to use it. Strategic communication offers several benefits, such as building situational awareness, countering the spread of rumors and disinformation, informing and educating citizens and supporting informed decision-making and crisis management. These benefits are highly correlated with the implmenetation of proper interagency collaboration mechanisms.

It is critical for EMBs to establish a trust-based relationship with voters and other stakeholders and be regarded as a primary, reliable source of information on electoral matters. Public disinformation and fact-checking registers online by EMBs can be an effective tool for this purpose, as it emerged from the research. These registers can provide transparent and factual information on election-related issues, as well as a platform for citizens to report suspicious or false information.

Reputation management is essential for maintaining trust and mitigating the impact of malign attacks against electoral management in the information space. Proactively monitoring online narratives regarding elections and providing timely responses are measures that could help EMBs preempt or reduce the impact of attacks on their credibility, and demonstrate their commitment to transparency and accountability.

The research revealed significant attacks against EMBs and individuals in the field of electoral management initiated or disseminated by political figures and affiliated online media. Urgent action is needed to protect electoral officials in the information environment, with an intersectional approach that considers the harmful content's specificities and conduct targeting women and representatives of vulnerable and marginalized groups in electoral management. States and political stakeholders must make firm commitments to guarantee the independence of EMBs and protect elections in the information space, while respecting freedom of expression.

A concerning finding is that misleading information about voter registration has been repeatedly disseminated online with the intention of gaining access to personal data. These types of attacks can have a serious impact on the democratic process by potentially disenfranchising eligible voters. Therefore, it is crucial to ensure that voters can register and participate in elections without fear of their personal data being compromised.

Regulatory measures are part of the solution but pose several challenges. They must be carefully considered, to avoid limitations on rights and freedoms not become overly restrictive or oppressive. Also, regulation should be flexible enough to keep up with accelerated technological dynamics. Very importantly, enforceability should be considered, mindful of the global nature of the online space.

Codes of conduct and soft law are alternative methods to fill gaps where regulation is not in place yet or is impossible due to the risk of restraining political rights and freedom of expression. They were tested in different formats with encouraging results.

The research findings highlighted the complex role of media in the electoral information environment. On one hand, reliable fact-checkers and media play an essential role in verifying the accuracy of information related to elections circulated online. On the other hand, the study revealed multiple instances where online media sources acted as the originators or disseminators of mis- and disinformation. Therefore, supporting free and independent media and data verification organizations could help to create a cleaner and safer information environment for elections and electoral officials.

Educational programs for current and future electoral actors (youth) and a particular focus on improving critical thinking and media literacy among different audiences could further help limit the impact of misinformation and online aggression.

Abusive limitations to the freedom of expression and access to information were observed across the globe by state actors, under the pretext of tackling disinformation around elections. Of particular concern are Internet shutdowns, justified as a means to protect information integrity from malign actors. They are not considered a measure against online harmful practices, but rather a harm in itself and a violation of the freedom of expression and the right to access information.

Check back on this link periodically! More knowledge resources will be published soon.