The Motivation for Women in Politics

The Contemporary Politics of Women’s Participation and Representation in Africa

I am humbled to have been asked to write this foreword by the authors. My involvement in the report was mostly at a technical advisory level, which I hope has helped to shape this report. In much of the relevant literature, a huge debate is raging on the two cardinal principles of governance—namely, participatory and representative democracy. This means that countries, scholars and policymakers must prioritize not only representational aspects of democracy but also participatory ones. A report on women’s democratic participation in elections in Africa lies at the heart of this debate. In addition, the report is timely because the role of women in democracy and governance has become a topical issue globally, and an important part of the work for human rights and gender equality. Admittedly, Africa still struggles to elect women executive leaders to the highest echelons of the political spectrum, notably heads of state and government, prime ministers and senior ministers, especially in critical portfolios, such as defence, security, finance, intelligence and foreign affairs. Thus, a report on women’s participation will contribute immensely to the debates, policy discussions and activists’ efforts to promote women in leadership positions on the continent. It will ultimately help improve women’s overall empowerment in Africa.

In Africa, the desire of women political leaders, activists and thought leaders to be appointed at the highest levels of their countries’ political systems is unquestionable. Their passion to be agents of change who can make a significant contribution in society to dealing with scourges—such as rape and gender-based violence, marginalization, tokenism and several types of injustices against women—is also convincing. Given the dangers and pitfalls of patriarchy, including the entrenchment of oppressive or authoritarian governance systems in Africa and globally, women’s dissatisfaction with male domination in politics is justified and understood. However, a report such as this one should urge African societies to go beyond simply understanding or condemning such situations, since the status quo cannot be left as it is. If it is, this could compromise the fulfilment of the ideals of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Nairobi Forward-Looking Strategies (1995) and several other international instruments that promote women’s equality and participation in democratic processes in Africa.

Furthermore, the report seeks to highlight and supplement women’s struggles to achieve their socio-economic, political and other needs and priorities in Africa. As the relevant literature in this report attests, women’s liberation struggles in many African countries were largely about liberation from numerous forms of oppression, especially racism and colonialism, wage slavery and patriarchy. Therefore, the total liberation of African people will be incomplete if it does not address these women-specific struggles. Finally, since women usually constitute the largest number of voters on many African countries’ voter rolls, by emphasizing democratic participation, this report should benefit ordinary female voters. It should also be welcomed by researchers, policymakers, activists, diplomats and government officials, as well as women in civil society, community-based and non-governmental organizations, electoral management bodies and other areas that are normally linked to political power, governance and the struggles for freedom in our countries.

Kealeboga J. Maphunye

Former WIPHOLD-Brigalia Bam Research Chair in Electoral Democracy in Africa, University of South Africa (UNISA)

Fulbright Scholar-in-Residence, Lincoln University, Philadelphia (USA)

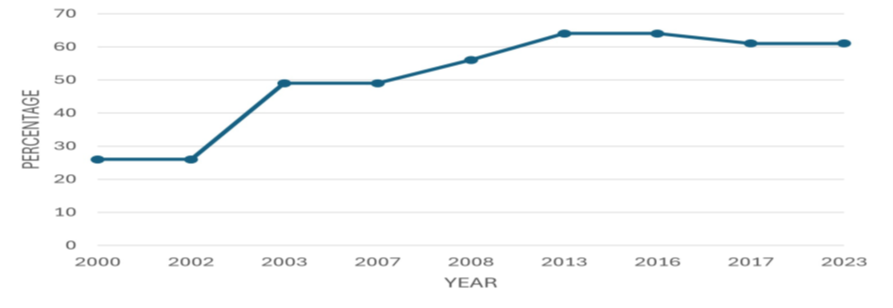

Women’s participation is a key issue in contemporary African politics. This is partly due to the gender gap that still exists, as reflected in women’s under-representation in political institutions and in leadership positions. Although it is encouraging that there has been an increase in women’s representation in legislative bodies, from 11 per cent in 2000 to 24 per cent in 2020, this is still far from the desired 50/50 gender parity. Indeed, some countries have seen reversals in the gains that had previously been made. The Africa Barometer 2024 on women’s political participation has noted sluggish growth over the last four years, where women’s representation has increased by just one percentage point.

In Africa, political leadership and representation remain largely male-dominated. This runs contrary to basic principles of democracy, given that women in Africa constitute at least 50 per cent of the population across all countries. This gender inequality in political representation and participation contradicts international law, in terms of the principles of human rights and equality between women and men as espoused in international agreements and conventions to which most African countries are signatories. The gender gap in political participation is problematic because the political space continues to foster unequal power relations, which give men an advantage over women. An inclusive political space is important because it is the arena where critical decisions are made on things like public policy, allocation of resources and setting development priorities. Women’s participation on an equal basis with men in this space is important to ensure that the decisions taken are equitable and fair in terms of outcomes, as is expected in a democracy.

Several factors contribute to women’s under-representation in leadership and decision making. The main factors relate to social norms, including religious and cultural beliefs and practices, that perpetuate the notion of the superiority of men over women, and a skewed division of labour that confines women to the private sphere of household care and domestic work while reserving the public sphere as a male domain. Increasing women’s political participation fundamentally calls for the dismantling of such social norms and practices, which exclude and marginalize women not only from politics but also from other spheres of life. Other factors that contribute to the limited participation of women in politics include the high cost of running political campaigns, and the lack of education, resources and skills to enable women to navigate the political landscape. Male domination of political parties has also reinforced the under-representation of women in leadership, which affects their prospects for appointment into legislative bodies.

Despite the challenges articulated above, there are some factors that have enabled women’s participation. A more favourable environment has emerged due to the adoption of international and regional frameworks that support women’s participation in politics on an equal basis with men. Most notably, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR, 1948); the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW, 1979); the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (BDPA, 1995); the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (also referred to as the Maputo Protocol, 2003); the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance (2007); and the 2008 Southern African Development Community (SADC) Protocol on Gender and Development. Most African countries have ratified these protocols and are in the process of domesticating them. Other enabling factors have been the role of women’s movements and civil society organizations, which have been active in advocating for women’s participation in politics.

Gathered from interviews conducted in all five of Africa’s subregions (East, Central, North, Southern and West), the evidence of the factors that motivate women to participate in politics was largely obtained from women politicians. A major factor which most respondents highlighted, was their desire and passion to be agents of change in their own societies, especially when they became aware of injustices against women. Others cited dissatisfaction with the male domination of politics. Several respondents pointed to prior experiences that had raised their consciousness about women’s needs and priorities—for example, when working in the civil society sector, or through activism in student movements. In some countries, the struggle for women’s liberation was part of a wider epistemic moment—not only for women but for men as well—and the realization that the liberation of women was a necessary pillar of national liberation. Ultimately, women’s participation in liberation struggles has given birth to feminist and other movements that have continued to advocate for women’s rights in all spheres in the post-independence period.

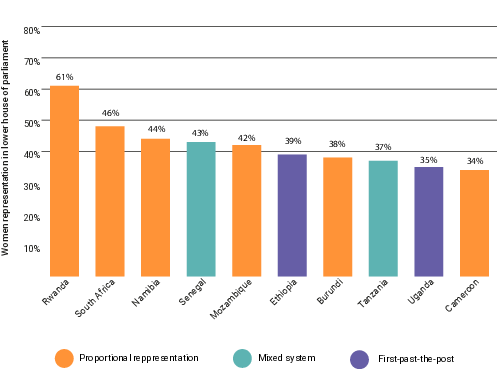

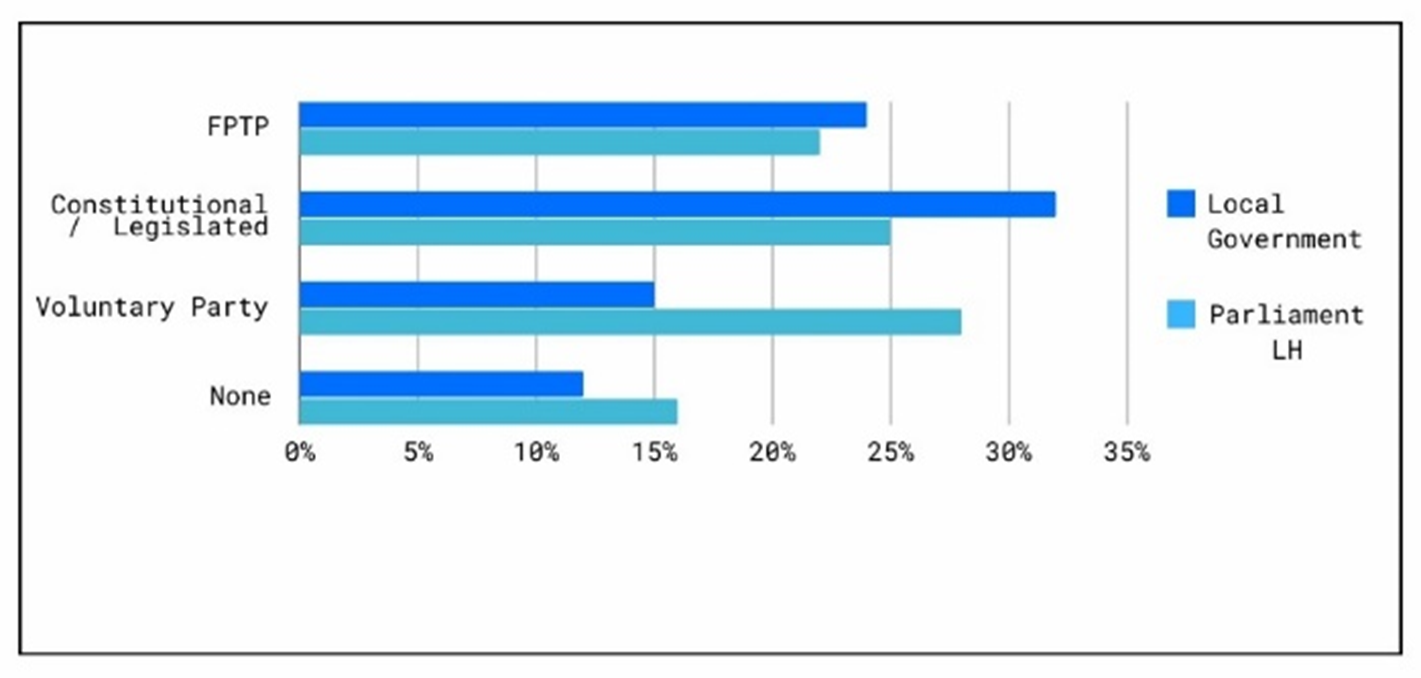

The different types of electoral systems have implications for women’s representation. Proportional representation (PR) electoral systems clearly create more opportunities for including minorities while majoritarian systems confer victory to one winner, leaving out minorities. The meteoric rise of women in political representation in Africa—for example, in Rwanda and Senegal—is largely attributed to more inclusive electoral systems and affirmative action policies. Despite this evidence, almost half of African countries utilize a simple majority system (23 African countries), while 18 countries use PR and 10 have a mixed system. The numbers of women representatives tend to be higher in the PR systems. Most African countries (40) have constitutional, legislated or voluntary party quotas, but there are challenges in complying with national frameworks, and political will is wanting when it comes to pushing for the alignment of administrative measures that would raise the number of women representatives. In total, 32 African countries that conducted elections between 2021 and 2024 missed out on the opportunity to use temporary special measures to increase women’s participation. This points again to a general lack of political will to address gender inequalities in the region. The region struggles with the institutional capacity to align administrative measures with electoral law, constitutional provisions, and regional and international norms and standards.

This report calls upon African governments to accelerate the implementation of the international, regional, subregional and national frameworks on women’s participation in politics on an equal basis with men. It emphasizes that, instead of a 30 per cent target for women’s representation in legislative bodies, countries should be aiming for 50/50 representation. It calls upon governments and other actors, such as the women’s movement, development partners and civil society, to build the capacity of women politicians by equipping them with knowledge and tools on how to run political campaigns.

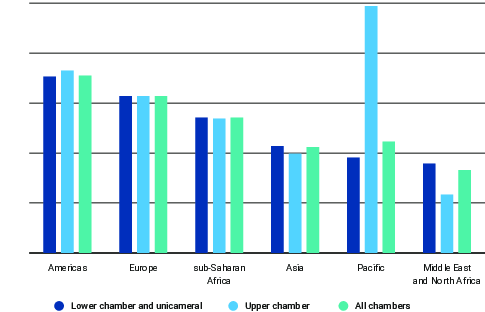

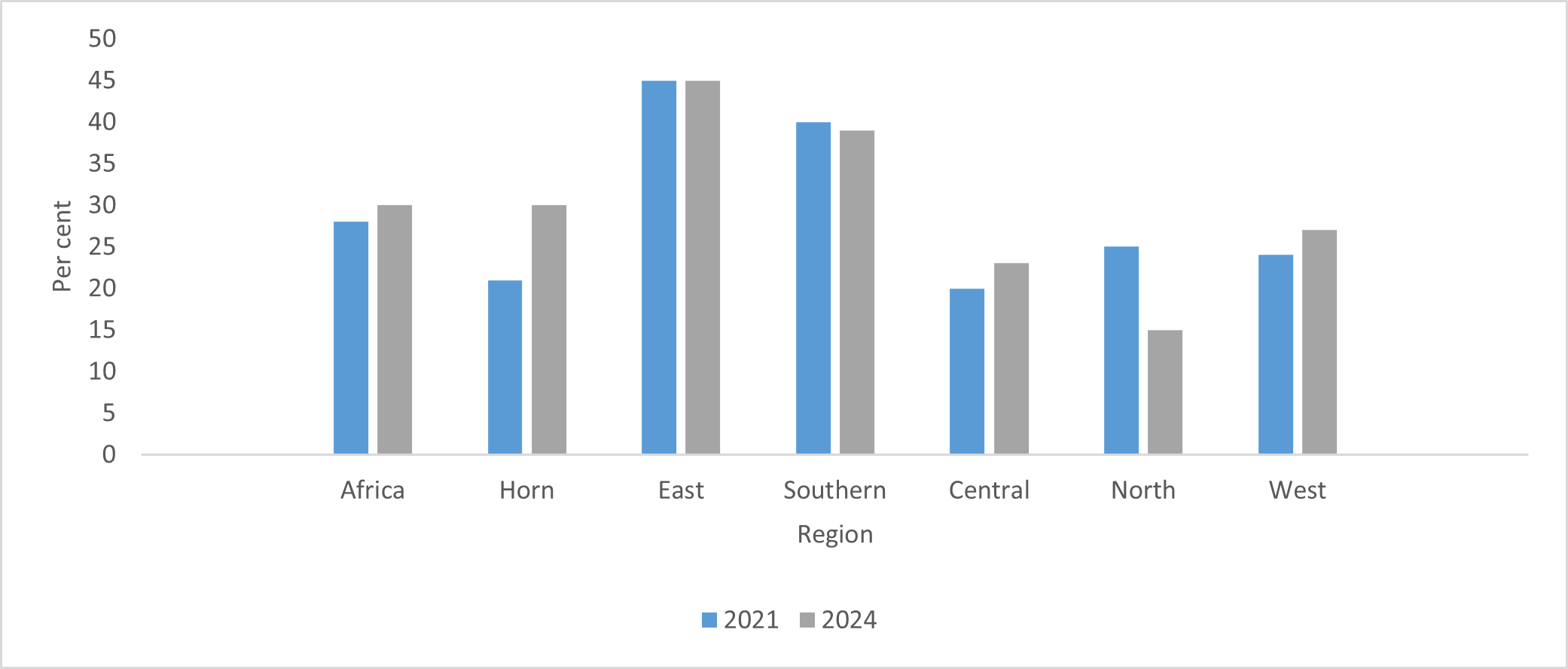

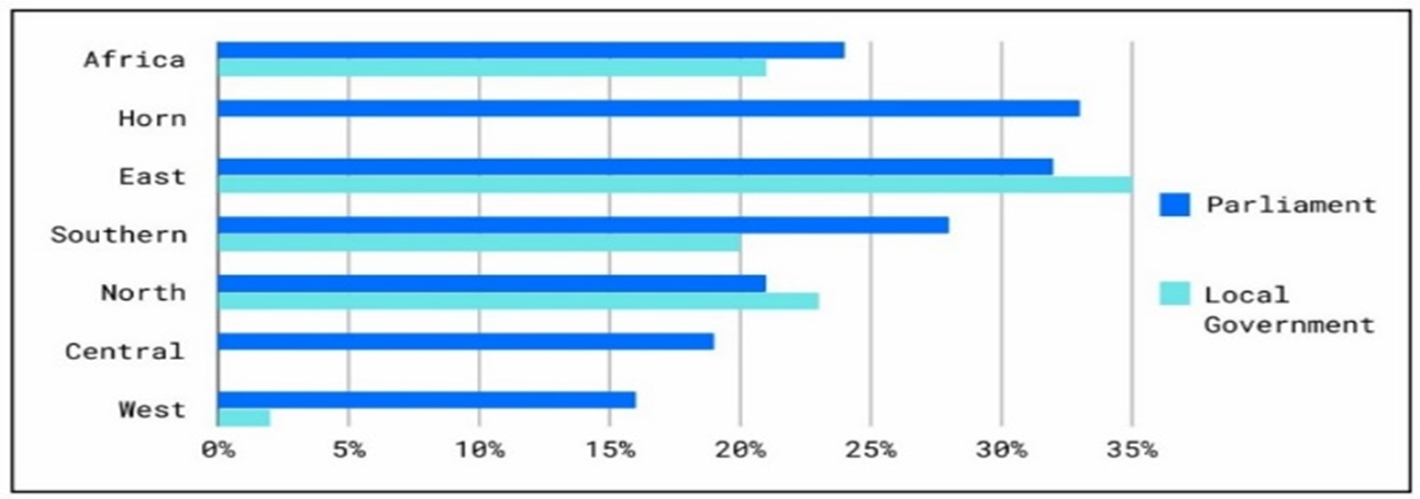

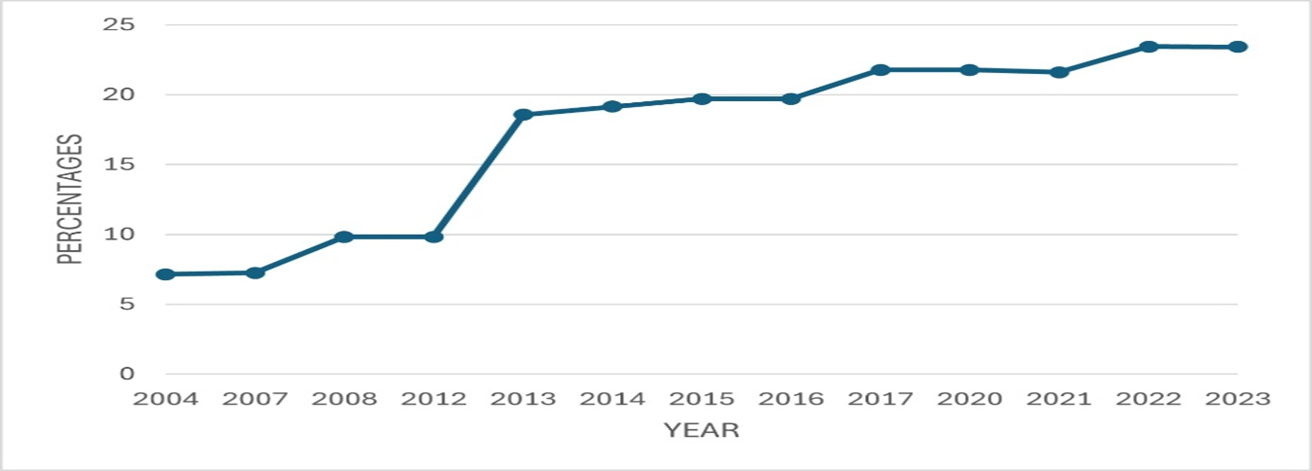

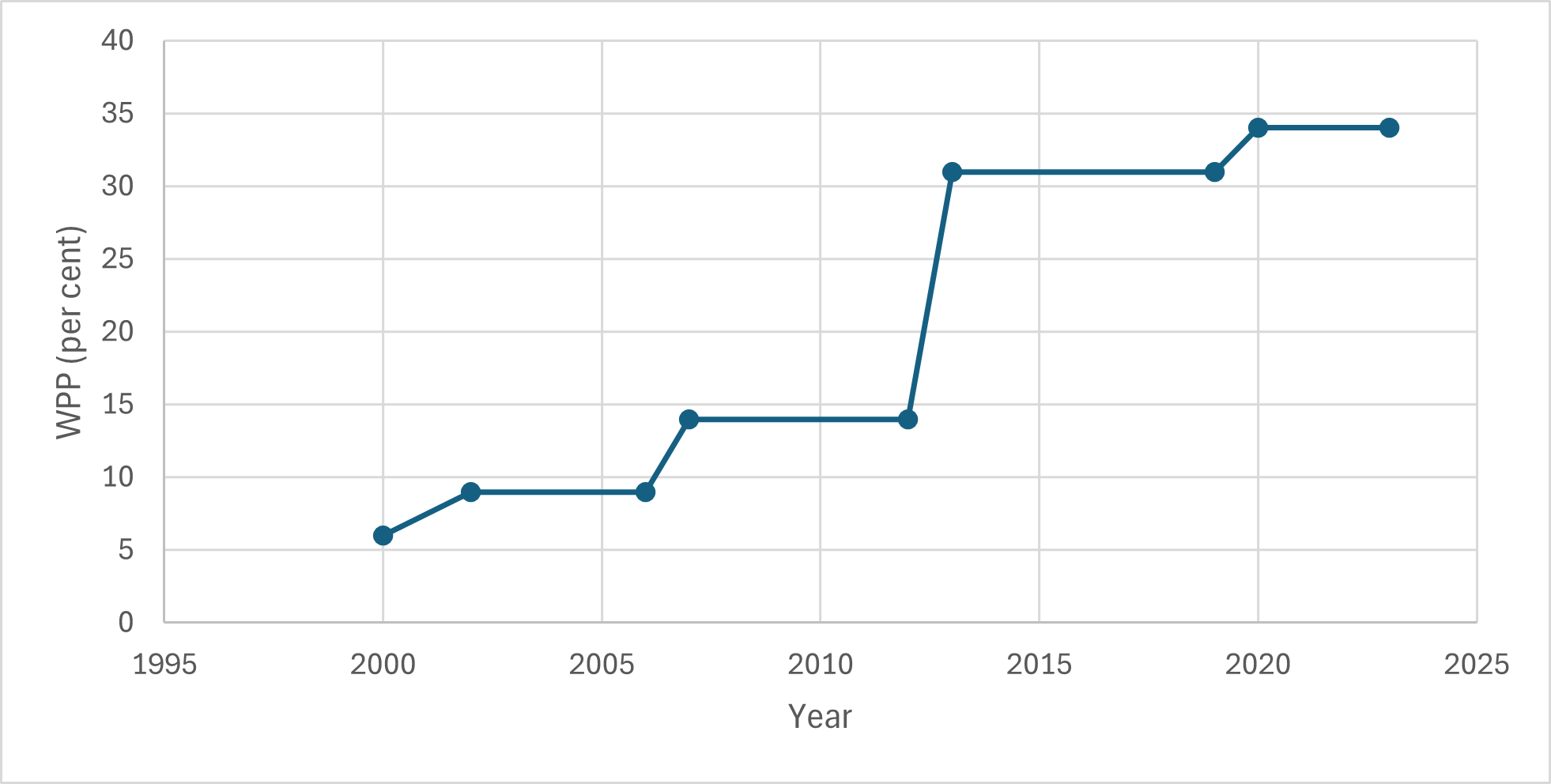

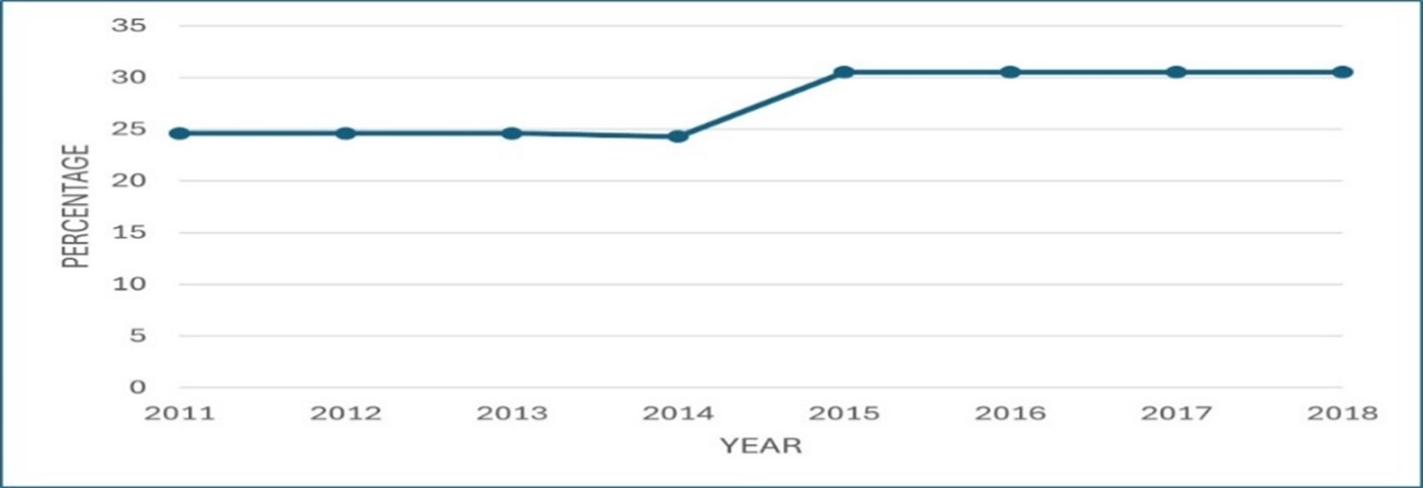

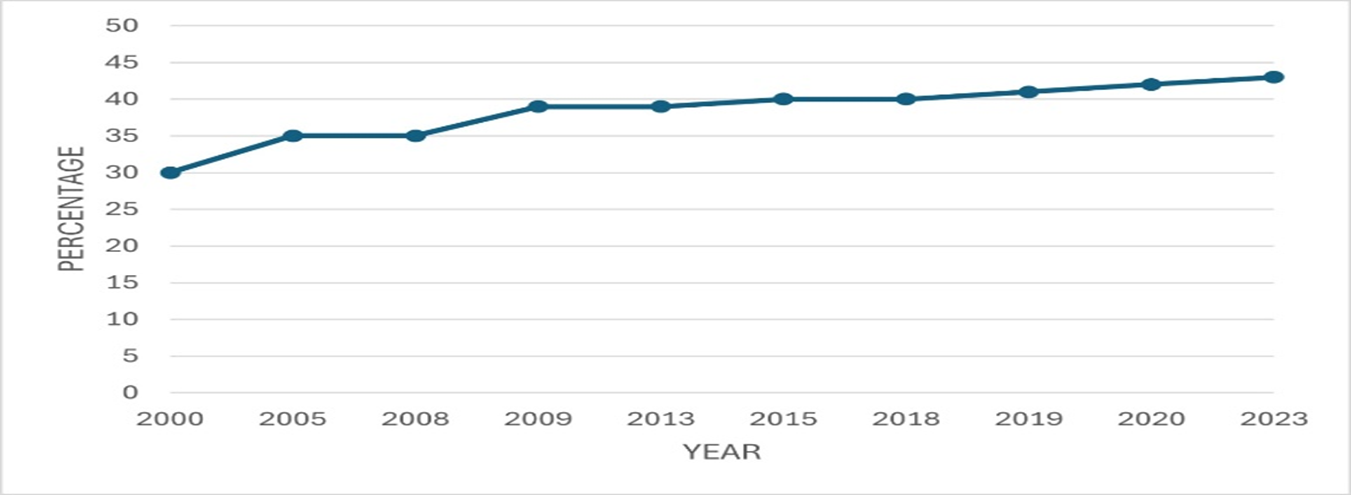

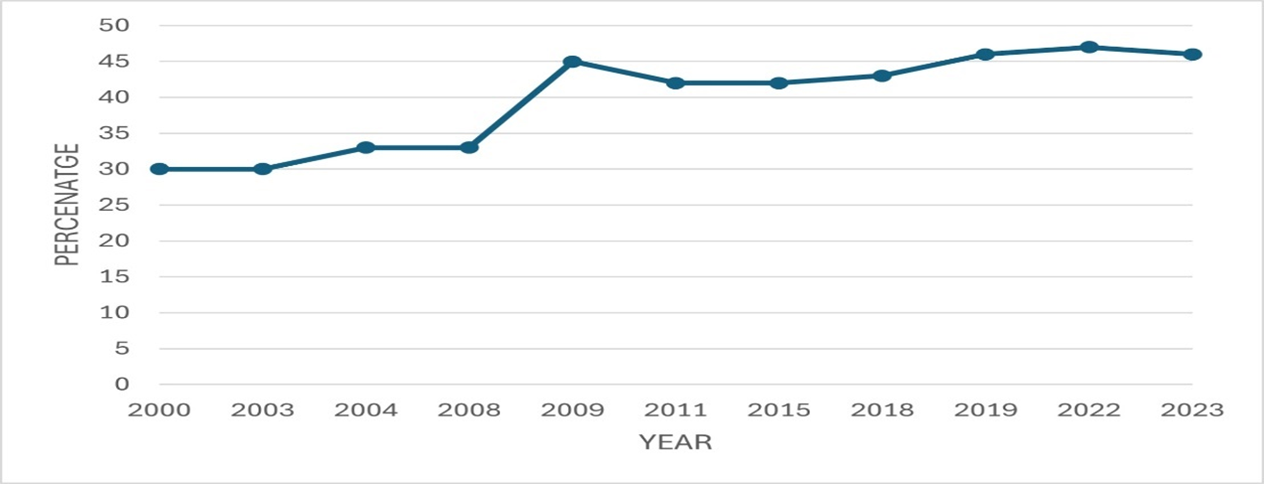

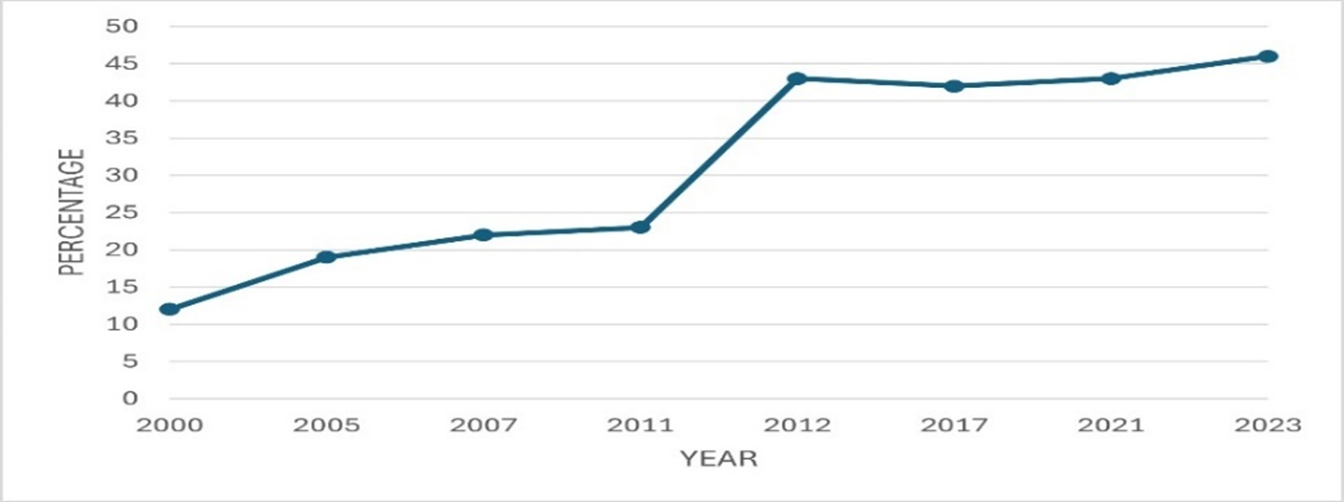

Globally, the race to increase women’s representation in line with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Target 5.5 on women’s political participation (WPP) is faltering, with overall figures still below 30 per cent (see Figure I.1). This is despite the presence of several protocols, norms and standards that heads of state have committed to. Democracy, and its principles of fairness, equality, accountability, justice and non-discrimination, serves as a model of governance for society that includes the promotion of gender equality and women’s empowerment (UNDP 2023). The set target of 30 per cent is deemed to be sufficient to achieve more than just symbolic representation, by creating a mass cohort of women legislators who can have a positive impact on policies and move the world closer to inclusivity in governance. The last two decades have seen a big increase globally in women’s representation in legislative bodies (13 percentage points between 2000 and 2020), although there were major variations across regions. In 2024 Africa has an average of 27 per cent women in the combined chambers of parliament, surpassing Asia, the Pacific, and the Middle East and North African regions (IPU 2024).

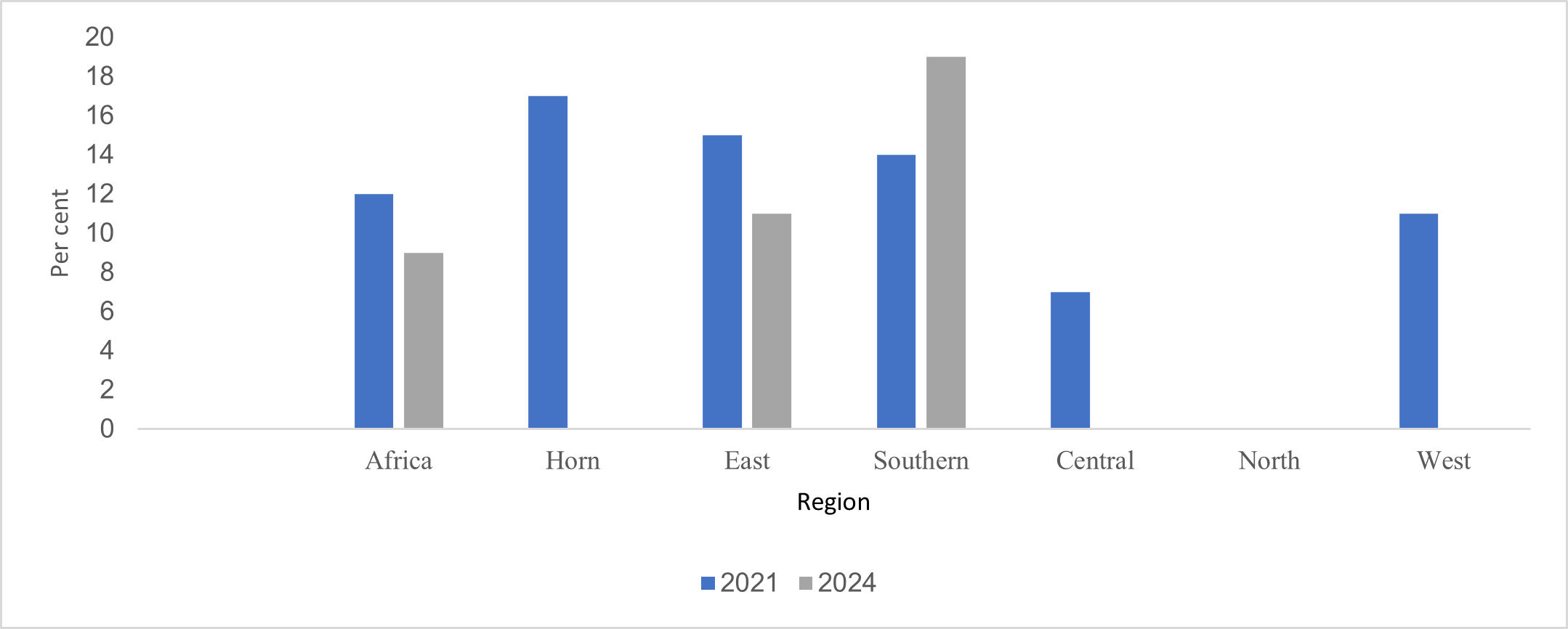

The Africa Barometer 2024 revealed that women’s representation in African parliaments has been rather stagnant since 2021, with an increase of just one percentage point in the four years to 2024 (International IDEA 2024). As Africa has held elections in over 32 countries in the last four years, the expectation was for an upward surge in the number of women legislators, in line with international and regional standards. The same slow place is noted in the Global Gender Gap Report 2024, where sub-Saharan Africa’s gender parity score of 68.4 per cent shows a 5.6 percentage point increase over a period of 18 years (WEF 2024).1

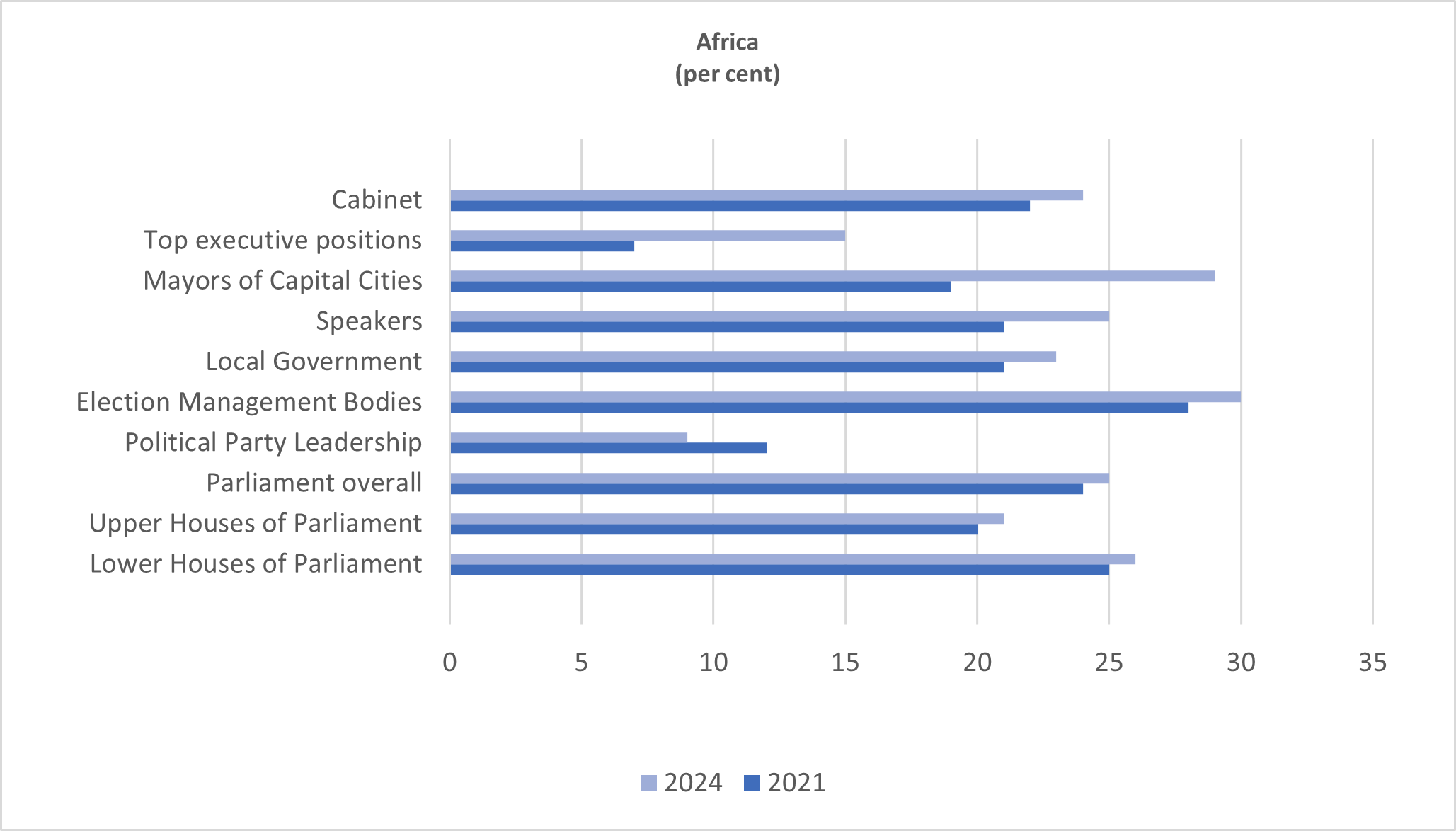

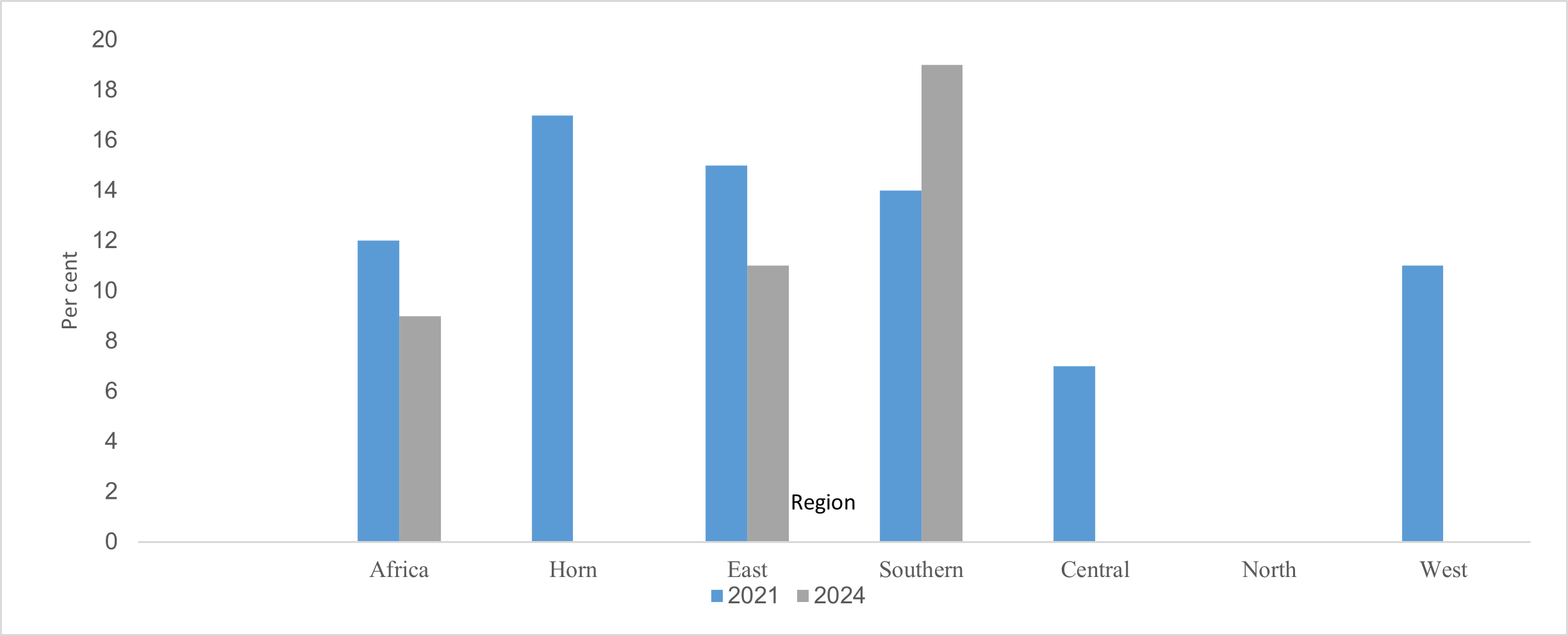

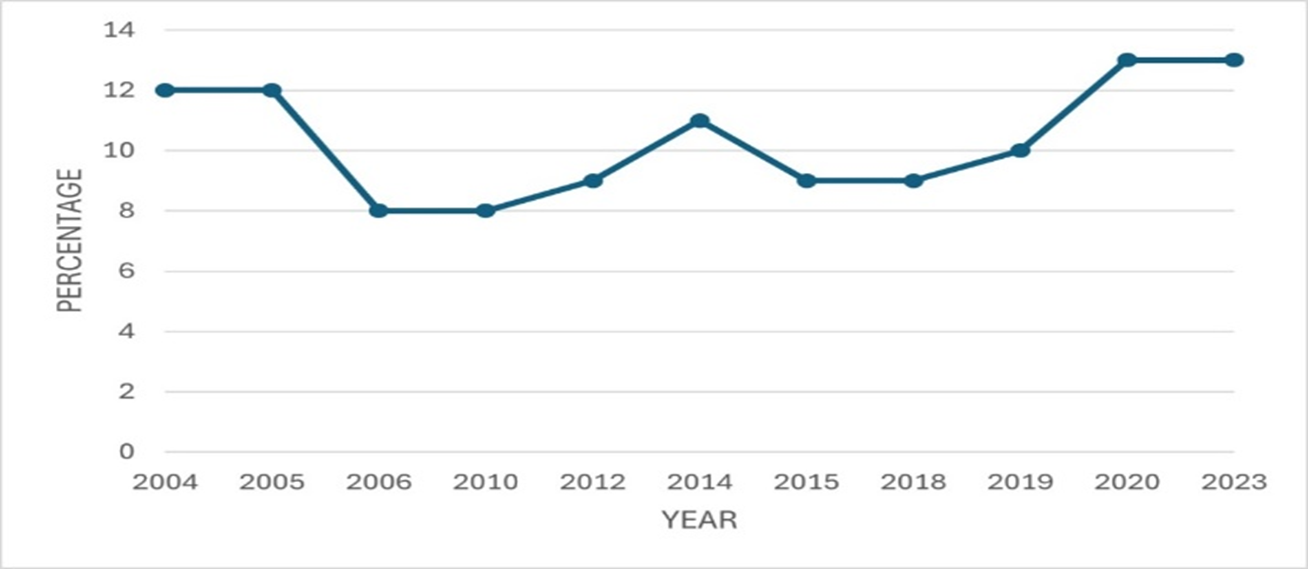

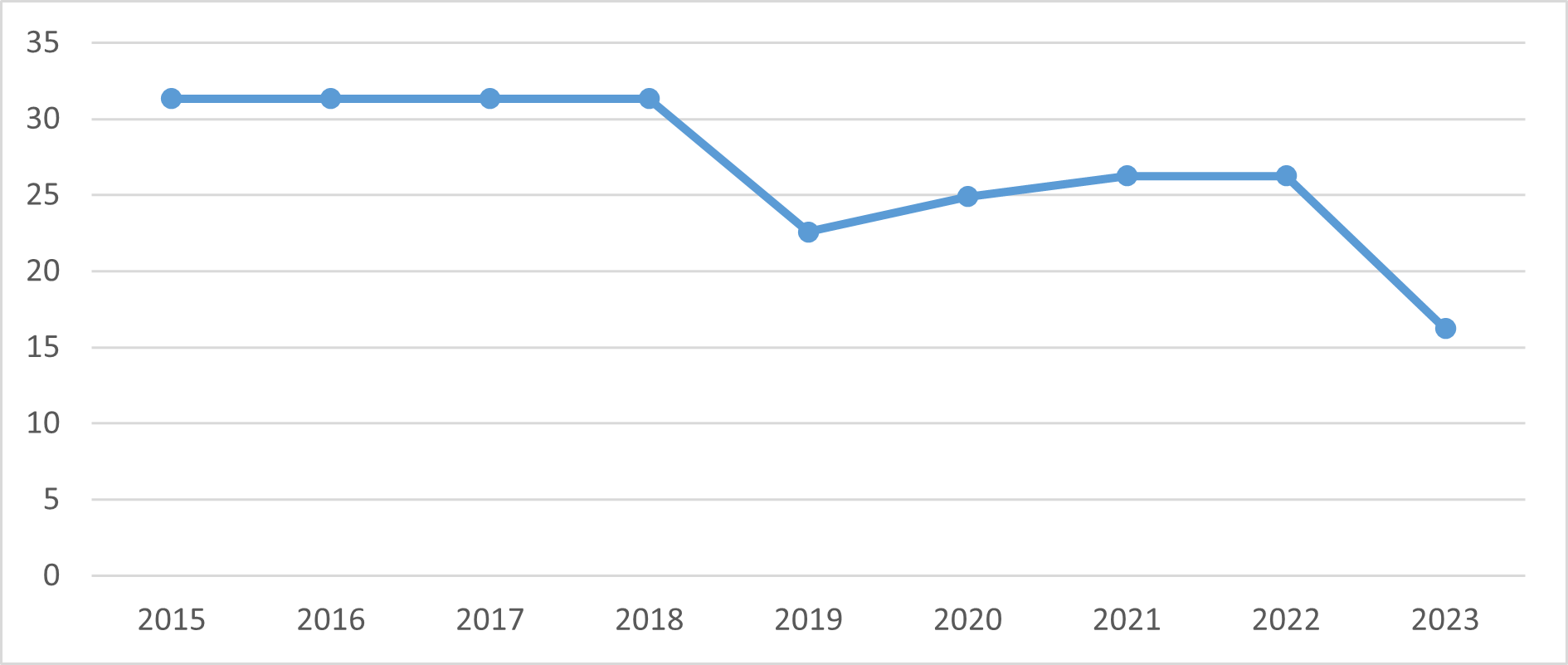

Holders of the highest political positions in African countries have remained mostly men over the last five decades. The 22 women heads of state across 17 different countries in the region (32 per cent since 1970) were either elected or served in an acting capacity (Bebington 2024). This translates into an average of one woman every two and a half years and demonstrates the overall sluggish pace of growth for women’s political leadership. In the lower chambers of parliament, Africa has an estimated 25 per cent women (see Figure I.2) and has struggled to reach this level. The important point is that the presence of women in leadership roles is a key motivator for other women to participate in politics at lower levels.

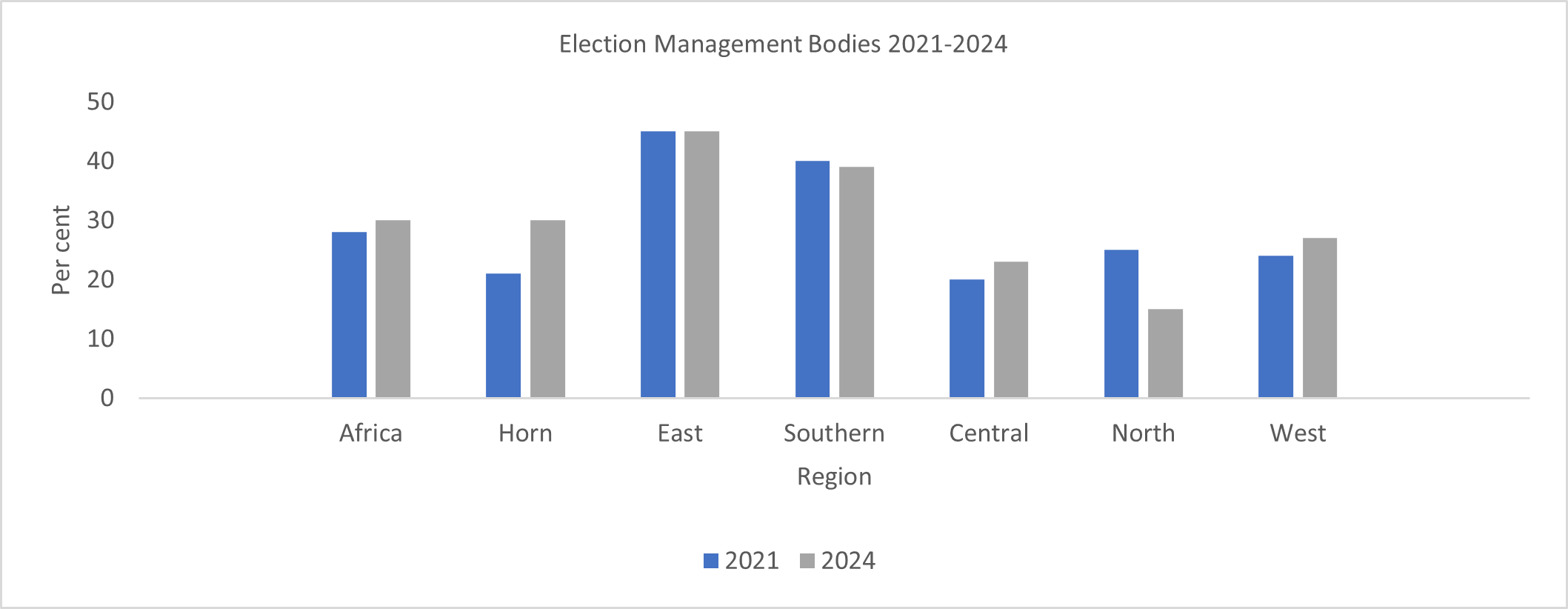

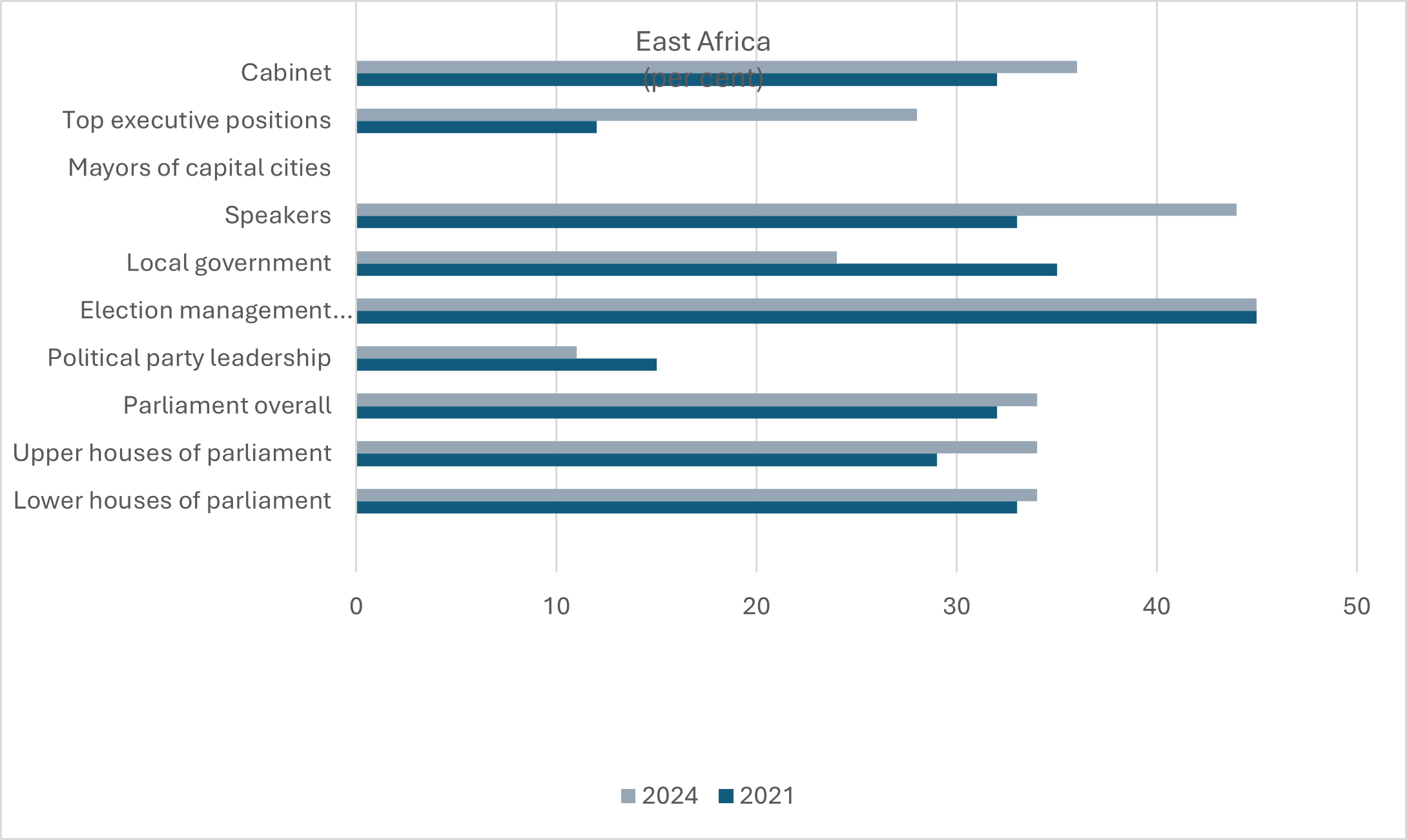

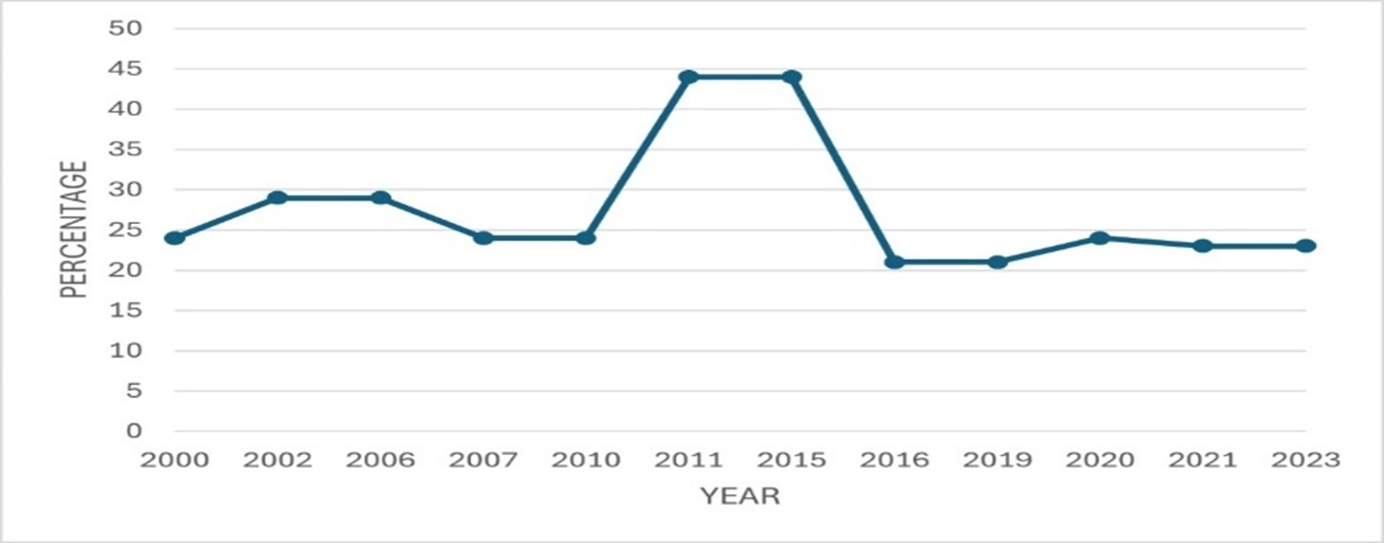

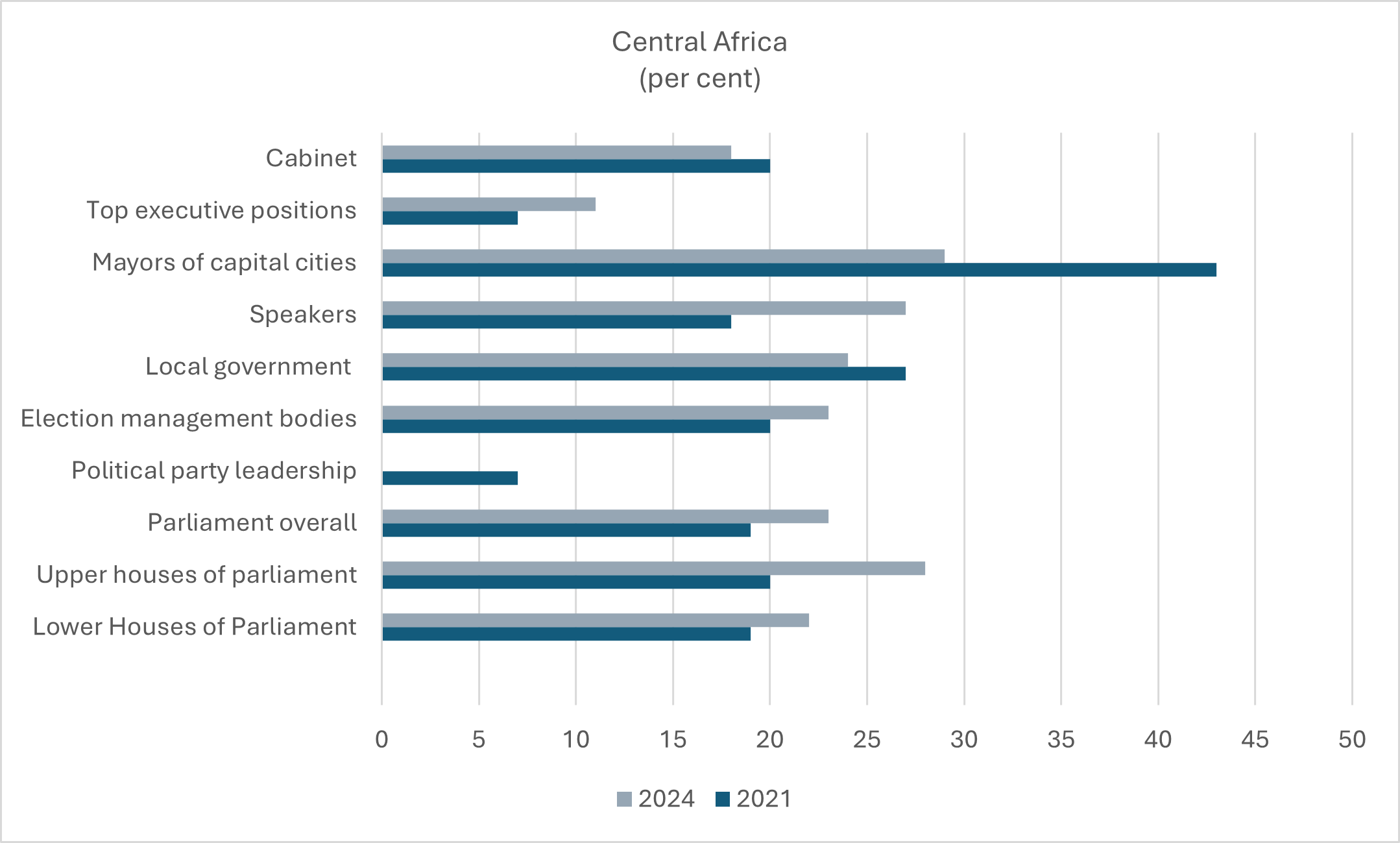

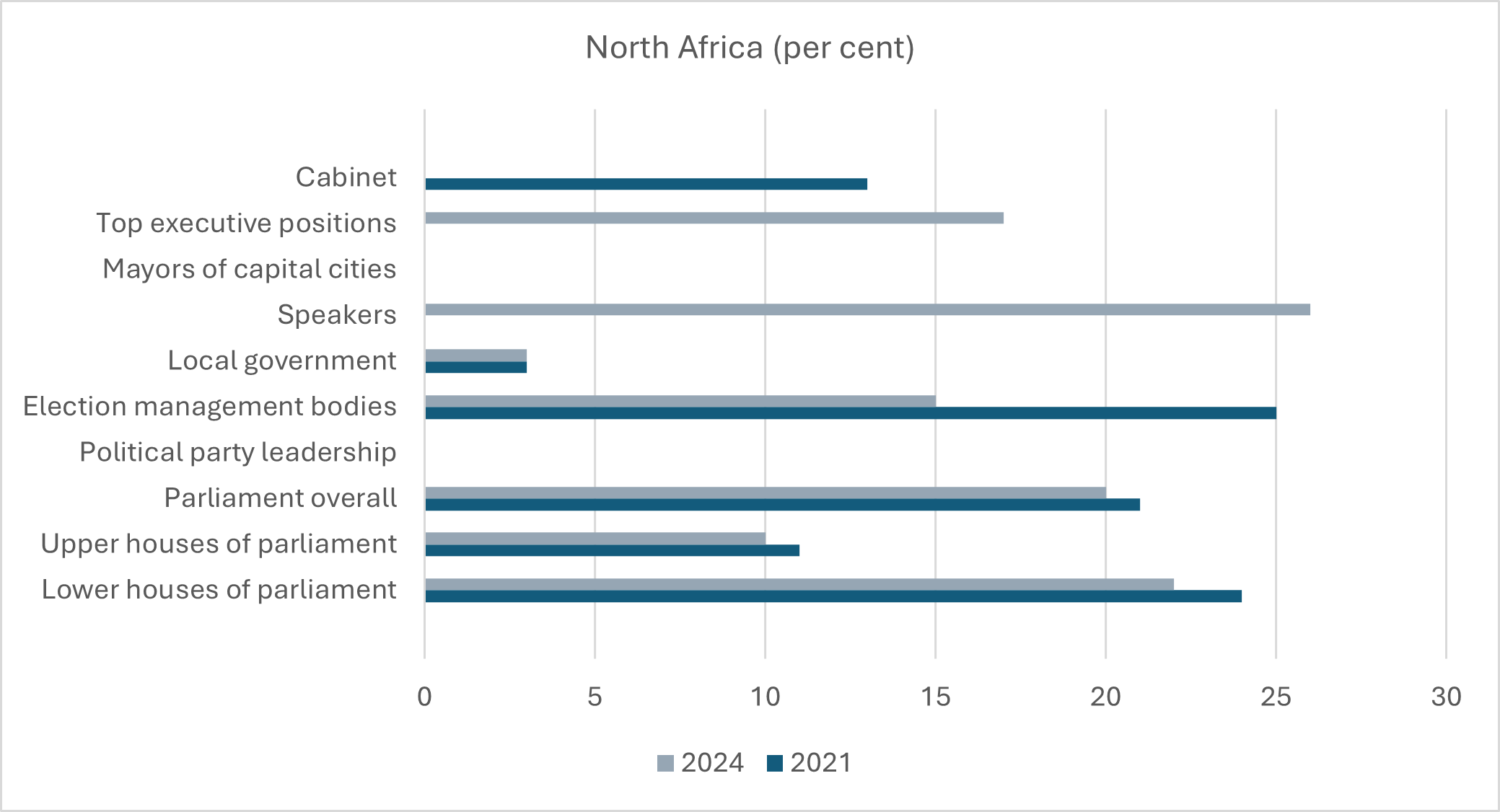

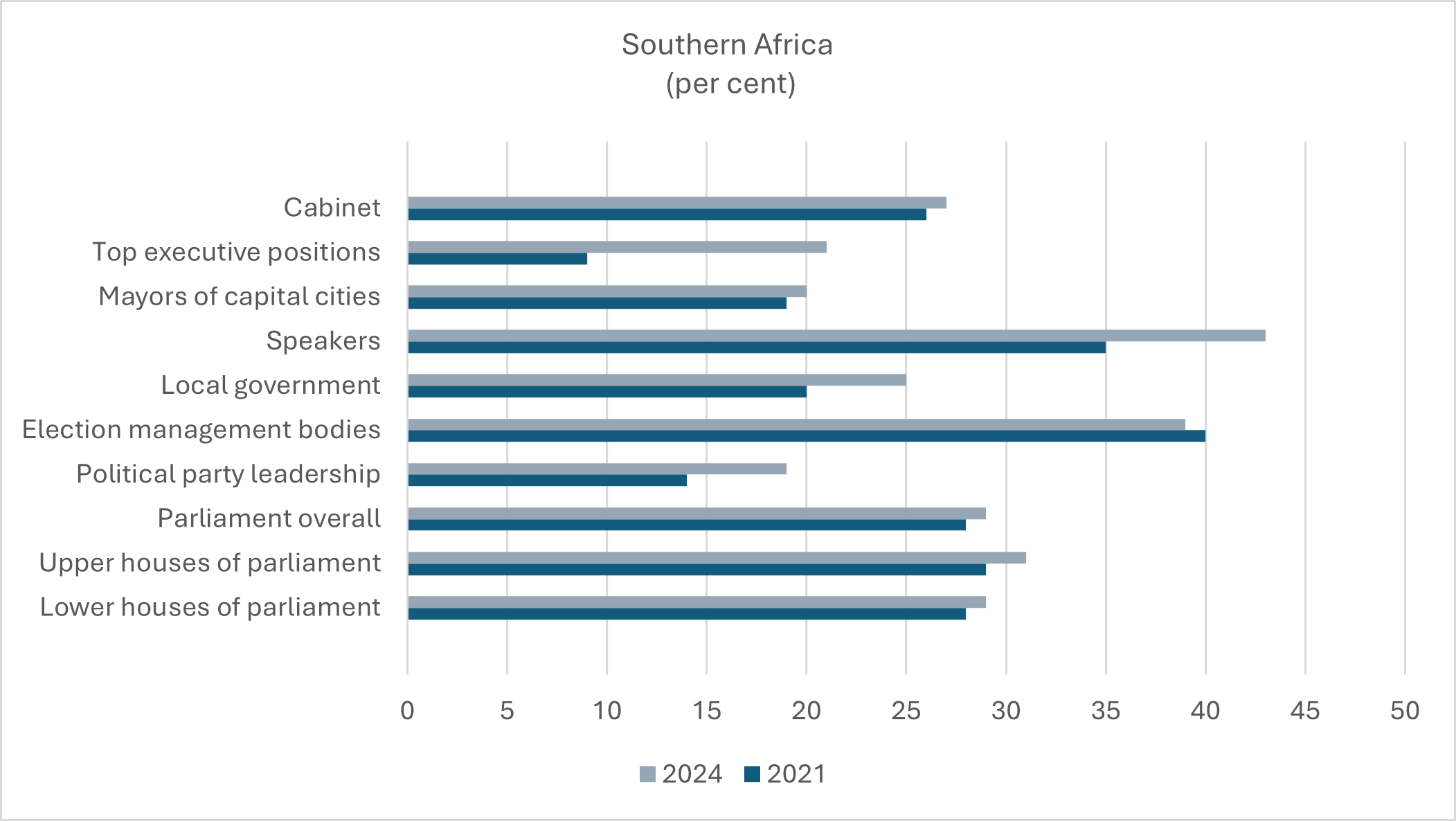

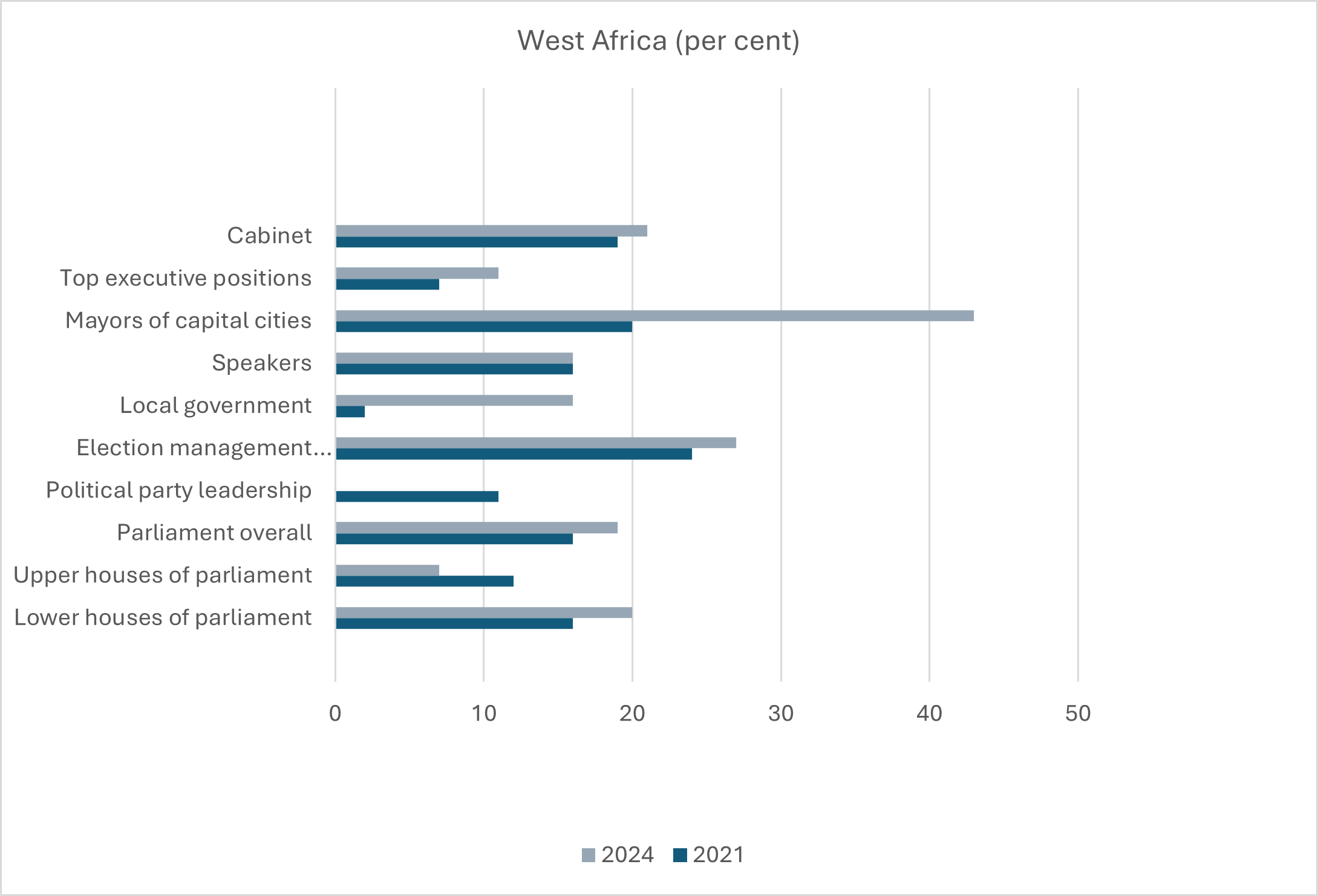

By 2024, none of the influential elected and appointed positions in Africa had reached 40 per cent for women’s participation. Only electoral management bodies (EMBs) had reached 30 per cent, the target set by the African Union and its subsidiary bodies the regional economic communities (RECs). EMBs have appointed women executives and many others in technical posts. The other top executive posts in government are at 15 per cent women. Among the elected positions, mayors lead the pack at 29 per cent women and have the biggest increase (10 percentage points) over a four-year period. In 2021, Africa had 10,510 parliamentarians (UNECA 2022), and just about 25 per cent of these were women. Despite how important parliaments are in meeting women’s needs, second only to local councils, which are at just 23 per cent, the increase in women parliamentarians over a three-year period is only 3 percentage points. Political party leadership remains at a dismal 13 per cent, up just 4 percentage points since 2021. The marginal increases all around indicate the need for more efforts to achieve 50 per cent parity in African parliaments. All African countries have committed to meeting the target of women holding at least 30 per cent of parliament positions by 2030. There are wide variances among African countries on this issue, with some making significant progress and others seemingly paying lip service to the commitment. African governments have missed the opportunity to address this gap that the many elections in Africa over recent years have presented.

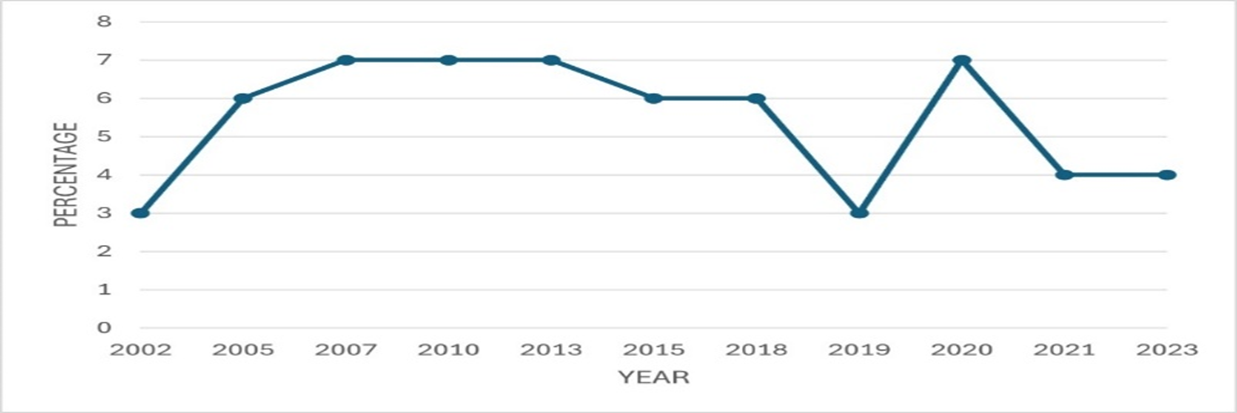

From the 2000s, levels of women’s participation in parliament hovered around 13 per cent, and by 2023 this had risen to about 26 per cent, with the pace of increase remaining at an average of 2–3 percentage points every two years (IPU 2017). The high levels of women in parliament in a few countries—Mozambique, Rwanda, Senegal and South Africa—pushed these figures up. Despite being half of the world’s population, women make up just 22.5 per cent of legislative seats worldwide (IPU 2017). The cause of this disproportion is rooted in cultural, socio-economic, religious and political factors, among others. For instance, Tremblay (2012) observed that Islamic beliefs on the roles of women in society is one cultural factor that has been used to explain low levels of women’s representation, while Christian Protestantism is viewed as producing more favourable results. Systems that provide more equal access to gender roles and enable women to access higher education are some of the cultural challenges that yield more positive levels of women’s representation (Tremblay 2012). With better socio-economic conditions that enhance the overall quality of life for women to build their capacity in engaging in public affairs, more will likely opt to participate in politics.

Through the many international and regional protocols on gender, African countries have the required policy and institutional frameworks to close the gender political participation gap. Many African countries have ratified conventions, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR 1948), the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW 1979), the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (2003, the Maputo Protocol)2 and the 2008 Southern African Development Community (SADC) Protocol on Gender and Development, which are all geared towards achieving gender equality in decision making at all levels by adhering to non-discriminatory policies (Meena 2018). Although all countries have some revered women leaders and heroines, the prevailing cultural and social norms continue to keep women out of the political arena as leaders. Regardless of these obstacles, many women from diverse settings have pushed back on the exclusive male-dominated political culture and are making inroads into high-profile political spaces. What then drives these women to force inclusion and how do they strategize? What motivates them to enter these rather closed spaces?

This publication attempts to highlight the resilience of women politicians and their supporters in contexts where political gatekeeping and electoral dynamics undermine their participation, making access to the political space a privilege for which they have to fight. It critically analyses factors that motivate women’s participation in politics, by identifying, assessing and documenting the current situation with respect to women’s participation in politics in the African region. Understanding these motivating aspects, teasing out the key influences and defining the attitudes and mindsets that drive women’s political participation is essential for designing mechanisms to expand women’s inclusion. Women’s political representation is defined as the proportion of seats held by women in elected and appointed positions. In this report, political participation includes a broad range of activities through which people develop and express their opinions on how they are governed and try to take part in shaping the decisions that affect their lives. Participation encompasses active engagement that is demonstrated through party membership, voting and contesting elected offices.

I.1. Why do women’s participation and representation in politics matter?

Women make a significant difference in politics; they bring much needed sobriety and the equilibrium required to tackle political and societal matters sustainably (interviewee). Research has shown that women’s political leadership has several societal benefits, such as inequality reduction (WEF 2017), improved cooperation across party and ethnic lines, and increased prioritization of social issues, such as health, education, parental leave and pensions (Markham 2014). Additionally, WPP has been shown to be particularly influential for women in their communities. Issues such as female voter turnout and public service responsiveness to women in general can be attributed to the presence of women in decision-making positions across the public and private sectors, influencing policies.

Dahlerup (2003) justified the inclusion of women in politics in three ways: the pursuit of justice as equity, the fulfilment of women’s lived experiences, and the fact that they represent specific interests. That women make up half the population means that they have the right to half the seats in all public office. This is a logical conclusion drawn from the fact that it is in the interest of justice to have women represent themselves. This has driven many of the legislative approaches to women’s representation in Africa. Another argument emphasizes the different experiences of women, whether physically or socially constructed, and this ties in with the concept of gender responsiveness that calls for attention to the specific needs of women that merit representation. This line of thinking remains difficult to translate into action in Africa, where many policies and services do not respond to women’s needs. For instance, women have reported that community meetings are very often organized around 18:00 in the evening, but that coincides with dinner preparation time and attending to children after school (interviewee, Nigeria 2024). More importantly, women’s interests are not necessarily aligned with men’s interests; hence, they must have space to represent their own.

African Union member states are proactively working towards achieving equal representation of women and men in politics and in decision-making positions at all levels, such as cabinet, parliament and local authorities. Despite these efforts and several declarations, statistics show that there are still few women involved in key political positions and national decision-making platforms. The patriarchal nature of most public institutions, and the toxic masculinity of political affairs, deters women from participating equally in politics in many African countries.

I.2. The root cause of women’s under-representation in politics: A framework for analysis

The under-representation of women in African politics is no mere coincidence. This report draws on feminist analyses to argue that the many barriers hindering women from politics are fundamentally rooted in the unequal power relations between women and men at all levels in Africa. Unequal power relations have created a gender division of labour, where women have been assigned roles and responsibilities confined to the household. Their main roles are reproduction and care and domestic work. For men, they are not only leaders in the home but in the public sphere as well. Because of this division of labour, over the years, women have become marginalized and excluded from leadership and decision making both in the private and public spheres, including politics. As a result, most decision makers in African parliaments, local government, government ministries, industry and even civil society tend to be male.

Unequal power relations between women and men have been entrenched or embedded in all segments of society through factors such as social norms, religious and other beliefs about the value and worth of women in relation to men, and discriminatory laws and policies that give preference to men over women in labour markets, wage structures, financial markets, industry and communities. Feminist scholars, such as Ahikire (2019), have articulated in very clear terms the nature of patriarchy and the gender hierarchies and inequalities that still exist in most African societies. A feminist framework is therefore best for problematizing the struggle for women’s rights, as it advocates for the transformation of power structures and practices embedded in institutions. This report analyses the systemic nature of patriarchal beliefs and practices, and how they have contributed to the marginalization or even exclusion of women from leadership and decision making in the political arena. It argues that the quest to ensure that women participate in politics on an equal basis with men fundamentally depends on the ability of African governments and other actors to dismantle the root causes of bias and prejudice against women in all spheres of African societies.

I.3. The gender dimension of political participation

Gender remains a contested topic. Many of the terms that form part of the discussion are often used interchangeably—for instance, gender equity is often used to refer to gender equality, but it is important that a distinction is made between these two concepts. This is to allow for reflecting on divergent understandings of gender differences and formulating appropriate strategies to address them. Bangani and Vyas-Doorgapersad (2020) point out that gender equality denotes women having the same opportunities in life as men, including the ability to participate in the public sphere, while gender equity denotes the equivalence in life outcomes for women and men, recognizing their different needs and interests, and requiring a redistribution of power and resources. Gender equity goes beyond equality of opportunity by requiring transformative change, and this largely occurs through political participation. This brings it closer to the concept of gender responsiveness (Bloom, Owen and Covington 2003). A gender-responsive approach considers the design of institutions, systems and facilities to challenge forms of gender inequality and unequal power relations, while improving women’s lack of control over resources. Such an approach is important for creating an environment that supports and enables women to realize their full potential. This conceptualization brings out the distinction between gender equity and gender equality with a gender bias, which refers to the displays of favouritism to a specific gender resulting in unfair treatment.

It is therefore imperative to scrutinize the region’s normative frameworks and political institutions for both gender sensitivity and gender responsiveness. Gender responsiveness is an essential element of inclusive governance that is central to the achievement of the SDGs, yet it has not received much attention from regional policymakers. The failure of almost all African governments to implement many of the gender protocols partly explains the lack of gender responsiveness and gender sensitivity within the frameworks themselves. Individual countries have the responsibility for translating the many protocols into concrete activities that heads of state commit to, which is why it is also necessary to analyse the national-level political culture in the selected case studies.

Since the third wave of democratization started in the

Some studies have argued that women experience differential costs in terms of running for political office. This relates to the costs of competing for office that vary between women and men due to the gendered nature of household or family roles, which cripple women’s political ambition, as do complex electoral processes (Lawless and Fox 2005). Although there is now a shift in perception, with the younger male generation embracing women’s leadership, there remains a general view among the older generation that women are unsuitable for office (Lawless 2015), which is believed to contribute to voter discrimination at the ballot box (Erskine 1971; Ferree 1974). However, if women are fielded by political parties that will foot their campaign bills, then these perceptions and attitudes will change. In any case, many women who have held high political office have excelled, at times outperforming their male colleagues, and debunked these conjectures.

Scholars of women’s representation have mainly focused on descriptive representation, referring simply to the proportion of representatives in legislative bodies who are women. In many African countries, there has been a tendency to emphasize descriptive representation—rather than any other kind of representation—which refers to women representatives as being agents who stand in for the top leadership. This has been very common in dominant party rule systems, often aligned with strong-men rule (as in Eswatini, Uganda and Zimbabwe). However, the question is to what extent women representatives project the values of the women they represent. One example is countries where, for instance, politics and service delivery or any other political developments are attributed to the principal, the ‘strong man’ or benevolent father figure. In these scenarios, women’s representatives cease to represent the agenda of women and become overly concerned with their own political survival and selling the image of the father figure. This deviates from the principle that legislative bodies ‘should be an exact portrait, in miniature, of the people at large, as it should think, feel, reason and act like them’ (Pitkin 1967: 60). This has sometimes given rise to additional scrutiny of the calibre of women elected to parliament and often generated negativity towards women who pursue political office (Franceschet, Annesley and Beckwith 2017).

Political parties and electoral systems in turn influence women’s descriptive representation, through the processes for the selection and election of candidates. This theorizing can be questionable in Africa, where liberation and nationalist movements advocated for equality between the sexes, but very little has changed and still only small numbers of women are elected who had to conform to the party’s dictates. All of Africa went through decolonization but, since 1957, when Ghana attained its independence, none have prioritized the adoption of electoral systems that promote women’s election to parliament. The majoritarian systems that dominated the African landscape immediately after independence have been proved to work against women’s descriptive representation (Paxton and Kunovich 2003).

Another perspective, the substantive representation argument, portrays the role of women representatives as that of active agents who act for the principal (Pitkin 1967). The implication is that, when women are in elected positions, they are likely to pursue policies that advance women’s interests and well-being. Feminists find the agency of descriptive and substantive representation of women to be intertwined, since collaboration on promoting women-friendly policies is supposedly a natural act (Bratton 2005). The question, then, is: do numbers matter in Africa, and has the increase in women’s political presence in parliament led to substantial gains in women-friendly policies (Bauer 2012)? In Rwanda, women have made significant progress on many women’s rights due to their high levels of representation (Burnet 2008). In Zimbabwe, a woman-led political party, the Labour, Economists and African Democrats (LEAD), successfully blocked the policy intended to lower the legal age of consent from 16 to 12 years in 2021. In many countries, such successes have been sporadic, however, so it seems that political will on the part of women politicians is paramount in pursuing women-friendly policies.

Studies on Senegal often attribute the quick rise in numbers of women in parliament to a third school of thought, symbolic representation. This refers to women representatives as agents who are attributed a certain representative meaning for the principal (Lombardo and Meier 2014). Many political institutions demonstrate how symbolic representation works. For instance, cabinets are made up of appointed positions, but they are also sites of representation, where ministers are often chosen to represent specific groups at the highest level (Franceschet, Annesley and Beckwith 2017). This symbolism gives both the appointing agent and the appointees some desired status of inclusivity, and appeases the many audiences to whom the symbol is directed. By opening space for more women and appointing them in key positions, public attitudes realign positively. This symbolic representation of women is related to the social construction of gender roles and many post-liberation war governments in Southern Africa initially adopted this approach (Angola, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe). Presenting women as political actors was believed to change people’s attitudes, beliefs and assumptions concerning who had the right to govern. A problem arises when women either fail to perform in these positions or are not given responsibilities that give them actual power, so the whole act is regarded as tokenism. When women’s positions trigger positive outcomes, discriminatory attitudes towards women as political leaders change (Beaman, Pande and Cirone 2012). This links up descriptive representation with symbolic and substantive representation, which feminist scholars defend in the sense that merely having more women in legislative bodies is valuable if it leads to changes at a broader level. Women’s representation in Africa cuts across all these perceptions, while some countries may be more inclined towards one perception. In addition, the penetration of women into opposition parties challenges all these ideas, since they transcend all these categories and shape their own agendas that appeal directly to women.

I.4. Methodology

A qualitative research design was used in this study and interviews were designed to capture WPP challenges across different countries and identify initiatives that have yielded results. Eleven cases were selected across all five regions in Africa to ensure regional inclusiveness while adhering to principles of inclusivity and diversity. The countries do not claim to be representatives of the subregions but, rather, they speak to the diversity in the area and in the region at large. They cover the Lusophone, Anglophone and Francophone divides, the religious cleavages and modes of transition to democratic rule. Some countries had relatively peaceful transitions to independence and some experienced violent turbulence. Women politicians and men activists who support the advancement of women were identified in the 11 country cases—three from East Africa and two from the other four African subregions (see Table I.1)—and interviews were conducted on what motivates them to participate in politics. The East African region has three countries—Kenya, Rwanda and Seychelles—for two reasons. One is the need to showcase Rwanda, which is the country par excellence in terms of women’s representation and participation in leadership positions, and the other is to include a quite different country, Seychelles, which is a cluster of small islands with distinct state formation dynamics. Interviews were also conducted in other countries in these regions. Success stories from these interviewees on their lived experiences in political participation were collected to complement their life histories.

| Region | Countries | Gender gap 2023 |

|---|---|---|

| East Africa | Kenya Rwanda Seychelles | 0.708 0.794 – |

| Central Africa | Democratic Republic of the Congo Cameroon | 0.612 0.693 |

| North Africa | Sudan Tunisia | – 0.642 |

| Southern Africa | Mozambique South Africa | 0.778 0.787 |

| West Africa | Nigeria Senegal | 0.637 0.680 |

The following data collection techniques described below were used.

Desk study

Secondary sources on drivers of WPP and representation in politics were derived from a variety of publications. These included a comprehensive review of the available literature on women’s participation and representation, and progress reports compiled by different stakeholders in the region and other actors. Some of the key resources were the Africa Barometer 2021 and 2024 on WPP, the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) database, International IDEA reports and databases and the World Bank database. Data was also collected from civil society organization (CSO) reports, government reports, academic and grey literature, and anecdotal evidence from the media.

A review of the relevant legal and administrative measures that guide the promotion of WPP included the policies and legislative frameworks developed at the global, regional and national levels. This focused particularly on the African Union, RECs and related African Union organs and specialized agencies which set the norms and standards on gender equality and women’s empowerment in Africa as informed by global normative frameworks, as well as the lived realities and needs of women and girls across the continent. Some of the key protocols for promoting women’s participation in politics are the Maputo Protocol and the SADC Protocol on Gender and Development. These frameworks were useful in tracking patterns on women’s participation in the region to get comparative insights on what works well in different contexts.

Key informant interviews

Most primary data was collected through key informant interviews conducted with select women politicians and activists in registered CSOs that work on gender empowerment. The range of interviewees included women members of parliament, representatives from political parties, men identified as allies in advancing the inclusion of women, women who lead political parties and gender-issue experts from CSOs. The selection of participants was determined by their media visibility, participation in political parties (as electoral candidates) and through the snowballing method. Interviews were conducted online (Microsoft Teams, Zoom or Google Meet, and WhatsApp calls).

Discursive analysis was used to interpret the data, and time series analysis for the quantitative data within the country case studies was important for assessing current political and governance dynamics vis-à-vis women’s needs and their reasons for participation in all aspects of political affairs. The transformation of governance practices to be inclusive of women and minorities in general has always been problematic as it is a moving target. There will always be advances and regressions in the inclusion of women in politics and this is largely affected by the macho political cultures in the region. The study therefore utilized specific retrospective questions to assess women actors’ insights.

The data collection was carried out in line with mainstream research ethical guidelines. Anonymity and confidentiality, along with the data itself, were secured throughout the study. Pseudonyms are used in the report to protect some of the interviewees in countries that are intolerant of outspoken citizens who challenge the status quo.

I.5. Structure of the report

This introductory chapter details the theme, gives an overview of women’s representation in Africa, lays out the conceptual framework and describes the methodology applied in the report. Chapter 1 defines the international protocols that guide women’s inclusion. Chapter 2 focuses on the regional policy and legal frameworks that motivate and encourage women to participate in politics. The region’s compliance with gender protocols is reviewed to assess political will and the drive to include women in politics. Chapter 3 presents an overview of political systems and the types of democracy and electoral systems in Africa and how these relate to affirmative action mechanisms applied to aid in the inclusion of women in politics. The aim is to ascertain the implications of different political systems and electoral quotas (where they exist) on women’s participation. Chapter 4 identifies the key drivers that motivate women to participate in politics and the obstacles that limit them. The lessons learned from these approaches to women’s participation feed into the last chapter on the recommendations. Chapter 5 discusses the different advocates and role models who spur other women into political participation. Chapter 6 presents the 11 country case studies that cover the region (geographically). These were selected to acknowledge the diversity in the region—across political systems, levels of democracy, religious differences, colonial legacy and liberation histories. This chapter involved the use of statistics to demonstrate the prevalence of ongoing policies and potential future problems in women’s equal participation in the regions. Chapter 7 is a critical analysis of the motivators for women in politics, based on data from the case studies. The focus is on the commonalities between the key motivators across the region and the strategies utilized in different political systems. The aim was to tease out the pathways for the inclusion of women in politics across the countries and highlight their regional policy implications. The last chapter on the conclusions and recommendations reviews the policy implications of strategies utilized by women politicians and other advocates across the case studies and their relevance for replication. The variations in women’s participation across countries made it possible to propose strategic interventions to enhance women’s participation in different settings.

I.6. Conclusion

This introductory chapter has presented the background to the report’s theme and taken a quick look at the status of women’s representation in Africa compared with other regions. Women’s participation is essential for achieving significant levels of development that can lead to stability and prosperity. This calls for a deeper understanding of what motivates women to participate in politics and the challenges they encounter. A panoramic view of this phenomenon is essential for designing intervention strategies that have worked elsewhere in the region.

Chapter 1 reviews the international frameworks that inform regional and national approaches to enhancing women’s inclusion in politics.

1.1. Introduction

Progress in the implementation of the global agenda for gender equality and empowerment of women in the political, economic, social and cultural arenas has largely been made possible because of concerted efforts by the United Nations. Working together with state actors and other interested parties, the UN has developed comprehensive and robust frameworks that spell out norms and standards on women’s participation in politics. This chapter provides an overview of the international frameworks that are central to the prioritization and institutionalization of gender equality and empowerment of women, and which guide countries to advance this agenda. These include the Charter of the United Nations, the UDHR, CEDAW, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (BDPA) and several UN General Assembly resolutions.

The frameworks are all aligned with the global 2030 Agenda on Sustainable Development, which contains a specific goal on gender equality and women’s empowerment, SDG 5. SDG 5 aims to achieve gender equality in all areas where women and girls are disadvantaged and experience inequality—for example, in education, health, access to wealth and resources. SDG 5 also seeks to eradicate inequality based on gender in employment, agriculture and industry, decision making and political participation. Target 5.5 seeks to ‘ensure women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making in political, economic and public life’ (UN DESA n.d.a). Women’s inclusion is bolstered by SDG 16, which promotes just, peaceful and inclusive societies. Target 16.7 relates to decision making, where the goal is to ‘ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making at all levels’ (UN DESA n.d.b). States parties are urged to promote and enforce non-discriminatory laws and policies for sustainable development.

1.2. A review of the international frameworks on women’s participation and representation in politics

This section reviews the specific provisions in international conventions and frameworks that relate to women’s participation in politics (see Table 1.1).

Charter of the United Nations (1945)

The preamble to the 1945 UN Charter presents a background which explains the rationale for advancing human rights as the guiding principle for its member states (UN 1945). The Charter was promulgated in the aftermath of the two world wars and can be viewed as a united response to the violence and other injustices that human beings had been subjected to. It was a commitment to prevent a repeat of that past and to create a more just world for future generations. The Charter establishes human rights, the dignity and worth of each human person, and equality between women and men as the foundations of justice and international law. This is reflected in the clause:

To reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small, and to establish conditions under which justice and respect for the obligations arising from treaties and other sources of international law can be maintained, and to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom.

(United Nations 1945: 2)

All African countries have signed the UN Charter and are bound by all its provisions.

| Framework | Provisions |

|---|---|

| Charter of the United Nations | Preamble |

| Universal Declaration of Human Rights | Human rights for all |

| International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights | Provisions on rights on political participation |

| Convention on the Prevention of All Forms of Discrimination against Women | Provisions on prevention of all forms of discrimination against women |

| Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action | Women’s rights are human rights Translating de jure equality into de facto equality or substantive equality |

| Agenda 2030 | Sustainable Development Goal 5 on gender equality and women’s empowerment |

| UN General Assembly Resolution RES/66/130 | Provisions on measures to ensure women’s full participation in decision making and politics |

| UN General Assembly Resolution RES/58/132 | Monitoring of electoral processes |

| UN Economic and Social Council E/RES/1990/15 | Introduction of quotas for women’s participation in decision-making positions and politics (30 per cent target) |

Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948)

The UN General Assembly adopted the UDHR on 10 December 1948 (UN 1948). In line with this declaration, women’s rights are human rights, so women’s participation and representation are not only fundamental human rights but also an indispensable foundation for sustainable development and democracy.

The UDHR builds on the UN Charter, which makes provision for equal treatment of women and men regardless of their class, race, ethnicity, colour or religion. It articulates in detail the human rights that all human beings are entitled to. The use of the terms ‘all’, ‘everyone’ and ‘no one’ clearly underscores that the provisions apply to both women and men in their diversities, whether based on sex, class, ethnicity, colour, age or religion (see Table 1.2).

| Article | Provision(s) | |

|---|---|---|

| Article 1 | All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. | |

| Article 3 | Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person. | |

| Article 5 | No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. | |

| Article 18 | Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion. | |

| Article 19 | Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers. | |

| Article 20 | 1 | Everyone has the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association. |

| Article 21 | 1 | Everyone has the right to take part in the government of their country directly or through freely chosen representatives. |

| 2 | Everyone has the right of equal access to public service in his country. | |

| 3 | The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government; this shall be expressed in periodic and genuine elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage. |

Article 1 of the UDHR states that the principle of equality applies to both women and men in any context or circumstances, in the political, economic, social, cultural or other arena. The political terrain in Africa tends to be fraught with violence, sexual harassment and intimidation, particularly among political parties which compete to mobilize membership. Due to unequal power relations in many parts of the continent, women are usually more vulnerable to such practices. The declaration makes provisions to protect both women and men in that regard. For example, women have the right to freedom of opinion and expression (article 19), while the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association (article 20) accords them space to participate in politics. The declaration also emphasizes that the legitimacy of a government is derived from people (women and men), clearly suggesting that women have as much right to choose a government for their country.

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966)

The UN General Assembly adopted the ICCPR in 1966 (UN 1966a). The covenant was motivated by a realization that the rights provided for under the UDHR could only be enjoyed if a conducive environment was created. The ICCPR was adopted to advance that goal. Two specific provisions relate to the issue of women’s participation in politics. Article 3 mandates states parties to the covenant to take measures to ensure the equal right of women and men regarding the enjoyment of all civil and political rights provided in the agreement. Article 25 indicates the specific areas for action to realize the mandate in article 3. The areas include provisions that allow every citizen to have the right and opportunity to take part in the conduct of public affairs, whether directly or indirectly through their representatives; to vote and to be elected at elections based on universal and equal suffrage by secret ballot; and to have equal access to public services in their country. In total, 53 African countries have signed the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (1979)

CEDAW was adopted in 1979 and came into force in 1981 (UN 1979). The convention builds on the UDHR by focusing specifically on a wide range of measures that member states should take to eliminate discrimination against women. The emphasis of the convention is on the need to ensure that both de jure (formal) and de facto (substantive) equality are achieved. This arises from the recognition that it is not enough to have anti-discriminatory laws; it is essential to ensure that they are implemented so that they eliminate discrimination wherever it occurs. Due to its comprehensive and practical orientation, the convention is also referred to as the International Bill of Rights for Women.

The convention defines discrimination as any distinction, exclusion or restriction made on the basis of sex which prevents women from enjoying and exercising their human rights on an equal basis with men (article 1). Such discrimination exists in political, economic, social, cultural and other fields. In a direct and explicit manner, the convention calls on member states to condemn discrimination in any form against women and to take concrete or actual measures to eliminate the discrimination.

CEDAW also calls on member states to take appropriate practical measures in a bid to eliminate discrimination against women (article 2). Examples include integrating or embedding principles of equality between women and men in national constitutions, adopting laws and policies that prohibit discrimination against women, amending or repealing laws that are discriminatory and replacing them with laws that advance non-discrimination. Article 4 on temporary special measures enables member states to implement practical but temporary measures to correct situations where there is discrimination against women. Affirmative action is justified under this clause until equality in representation (50/50 proportion) between women and men is achieved. Social norms, beliefs and practices that perpetuate discrimination against women are some of the deeply rooted factors in the exclusion or marginalization of women from the political, economic and social arena in African societies. They are the ‘engine’ that propagates, perpetuates or sustains discrimination against women based on their sex. Article 5 of CEDAW makes it clear that member states have an obligation to take appropriate measures to eliminate those social norms and cultural beliefs and practices that continue to preclude women from participating in politics. The need for measures to eliminate discrimination against women in public life recognizes that women are under-represented in the political sphere, both in terms of participation and decision making. In article 7, the convention calls on member states to take concrete measures to ensure that women participate on an equal basis with men in voting, running for public office and participating in the formulation and implementation of public policies. Member states are also called upon to ensure that women participate in decision making at the international level on an equal basis with men. In total, 52 African countries have ratified CEDAW.

CEDAW Optional Protocol (1999)

This protocol was adopted for the purposes of ensuring accountability by member states in implementing the convention (UN 1999). The protocol established a Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, whose function is to receive and consider complaints from individuals or groups among signatories that pertain to alleged violations of CEDAW. The protocol goes beyond the requirement that member states submit periodic compliance reports to the Board of CEDAW, to allow victims or representatives of victims of any discriminatory practices to seek recourse at the UN level.

The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (Fourth World Conference on Women, 1995)

One of the key assertions of the BDPA was that women’s rights are human rights, which emphasizes that the human rights provided for in the UDHR apply to both women and men. Section G on women in power and in decision-making roles contains a robust discussion of the under-representation of women in power and in decision-making roles at all levels, the root causes of that imbalance and the measures that countries can implement to redress inequities.

The BDPA places a strong emphasis on unequal power relations as the root cause of inequality between women and men in participation in politics, in the distribution of care work in the home, with respect to access to resources (land, credit, property), and inequality based on the social construction of the gender division of labour. Recognizing the structural and political nature of women’s exclusion or under-representation in leadership and decision making, the declaration advocates a redistribution of power that ensures women participate on an equal basis with men in the political arena.

In paragraph 181, there is an elaborate explanation as to why women must be equally represented in power and decision-making positions at all levels of government at the international, regional, national and local levels. The declaration states that women’s equal participation in decision making is not only a demand for justice or democracy, but it can also be seen as a necessary condition for women’s interests to be considered. Equal participation between women and men is a requisite for strengthening democracy and promoting its proper performance.

The BDPA contains comprehensive measures that countries can implement to redistribute power between women and men to achieve equality. These include mainstreaming gender perspectives at all levels of decision making; setting targets for women’s representation at those levels; ensuring equal access to resources such as land and finance, as well as access to training and technology; monitoring implementation; and formulating policies to guide political parties on the equal sharing of power between women and men, and achieving equal representation on electoral candidate lists.

ECOSOC Resolution (1996)

Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) Resolution 1996/6 was adopted in 1996 (ECOSOC 1996). ECOSOC mandated the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW), a UN agency dedicated to promoting gender equality and the empowerment of women, to coordinate the monitoring and reviewing of progress on the implementation of the BDPA. The CSW is also responsible for monitoring the mainstreaming of gender within UN bodies. In article 33, member states are mandated to implement the convention by setting up a focal point tasked with the responsibility.

UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on women, peace and security (2000)

The Security Council adopted Resolution 1325 on women, peace and security on 31 October 2000 (UN Security Council 2000). The resolution reaffirms the important role women play in the prevention and resolution of conflicts, peace negotiations, peacebuilding, peacekeeping, humanitarian response and in post-conflict reconstruction. It stresses the importance of their equal participation and full involvement in all efforts for the maintenance and promotion of peace and security. Political institutions involved in these efforts must involve women as key stakeholders.

UN General Assembly Resolution A/66/130 on increasing women’s participation in politics (2011)

This resolution (UN General Assembly 2011) on WPP is one of the most comprehensive resolutions to address the various barriers that hinder women from actively participating in politics (see Box 1.1). The resolution urges international and regional organizations and countries, within their mandate, to implement an extensive set of measures for the purpose of increasing women’s participation in decision making and politics. Box 1.1 lists the measures that the resolution proposes to address obstacles that women face in politics.

Box 1.1. United Nations General Assembly Resolution 66/130: Measures for member states to increase women’s participation in politics (summarized from the resolution)

- Eliminate root causes of discrimination against women.

- Improve women’s access to information and communication technologies.

- Act against perpetrators of violence, assault or harassment of women elected officials.

- Create an environment of zero tolerance for violent offences against women.

- Work on the inclusion of marginalized women.

- Conduct sensitization work with young women and girls on politics.

- Create an enabling environment for women’s political participation.

- Promote the granting of appropriate maternity and paternity leave to facilitate women’s political participation.

- Provide adequate access to quality education and healthcare for women and girls.

UN General Assembly Resolution 76/140 on improvement of the situation of women and girls in rural areas (2021)

Rural people in Africa have been left behind in several respects—politically, economically and socially. Due to higher levels of illiteracy, limited access to infrastructure and information, and the high cost of moving from place to place, rural women’s participation in politics tends to be more limited compared with those living in urban areas. This resolution (UN General Assembly 2021) addresses these challenges by calling upon countries to implement measures to ensure that rural women are also able to participate fully in decision making and politics. This resolution was adopted by the General Assembly on 16 December 2021.

1.3. Conclusion

This chapter has presented summaries of key international frameworks with specific provisions for advancing the participation of women in politics and decision making. These frameworks are comprehensive, and they address a wide range of issues that are fundamental to ensuring such participation. These include the principles of equality between women and men regardless of sex, class, race, age, religion or other attributes (UN Charter) and the universality of human rights, suggesting clearly that women’s rights are human rights (UDHR), and the elimination of any form of discrimination against women and girls (CEDAW). The BDPA outlines several measures that member states are called upon to implement aimed at increasing women’s participation in the political arena. This chapter has also shown how UN General Assembly Resolution 66/130 provides one of the most comprehensive frameworks for identifying various areas where member states must implement measures to achieve gender equality and the empowerment of women with respect to political office, electoral processes and democratization of their governance systems. These international protocols are all supposed to be domesticated at the national level. Some have been distilled by the African Union, which has come up with its own regional protocols to increase women’s participation in politics, and these are discussed in Chapter 2.

2.1. Introduction

This chapter focuses on the frameworks the African Union has developed to guide member states in the process of domesticating the universal UN principles and guidelines on gender equality and women’s participation in politics (see Table 2.1). Africa has several regional frameworks, including the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) (1981), the Protocol on Amendments to the Constitutive Act of the African Union (2003) and the Maputo Protocol (2003). Both international and regional frameworks are used to guide countries in domesticating agreed norms and standards that pertain to women’s participation in politics. These regional frameworks have become the yardstick by which regional bodies and the UN measure performance in respect of the advancement of women in the political arena.

| Framework | Specific provisions |

|---|---|

| Constitutive Act of the African Union (2000) | Women’s full participation in development |

| The African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (1981) | Articles 1–19 Reaffirmation of the UDHR Article 19: equality of all before the law |

| The Maputo Protocol (2003) | Equality of women and men before the law Article 9: women’s participation and advancement in politics |

| African Youth Charter (2006) | Articles 2(c) and 23 Ensuring empowerment of youth and their participation in decision making |

| African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance (2007) | Domestication of CEDAW Measures to promote women in decision making |

| Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want (2015) | Africa’s long-term vision: equality between women and men regardless of sex, class, age, ethnicity and race |

African Union Gender Policy (2009) African Women’s Decade, 2010–2020 (2009) African Union Strategy for Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment 2018–2028 (2018) | Policy guidance and strategic directions to member states to implement measures to achieve gender equality and empowerment of women |

| Solemn Declaration on Gender Equality in Africa (2004) | Framework for monitoring progress of member states in implementing the Maputo Protocol |

Constitutive Act of the African Union (2000)

Using gender-neutral language, article 13 of the Constitutive Act of the African Union (2000) makes provisions that point to equal treatment of women and men with respect to the participation of African citizens in the activities of the Union, in section 13.c on the promotion of gender equality, and section 13.l on upholding respect for democratic principles, human rights, rule of law and good governance. Article 17(1) is on the establishment of a Pan-African Parliament whose function is to ensure the full participation of all Africans in the development, economic growth and regional integration of the continent. While there is no explicit reference to women, the phrase ‘full participation of African peoples’ suggests that this regional parliament must ensure the participation of women and men without consideration of country of origin, race, ethnicity, age, income or any other characteristic. The Act was adopted by African heads of state on 11 July 2000.

The regional protocols may all be gender-sensitive, but gender responsiveness is left to each country’s administrative statutes on a case-by-case basis.

The African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (1981)

The ACHPR (African Union 1981) domesticates the UDHR at the regional level. This is evidenced in several articles, particularly articles 1 to 19. Regarding WPP, article 13 (also part of the UDHR) demonstrates the commitment of African leadership to that principle. The article guarantees the right of every citizen to participate freely in the government of their country, either directly or through freely chosen representatives in accordance with the law. The language in the text reflects the state of gender-sensitivity knowledge at the time of drafting the protocol. The understanding was that the provisions were applicable to all Africans irrespective of gender. Articles 10, 11 and 12 provide for the rights of freedom of association, freedom of assembly and freedom of movement, and employ gender-neutral language. Article 19 makes provision for equality for all before the law, as reflected in the UDHR. In essence, even though the ACHPR uses gender-neutral and in some instances, sexist language, it does make provisions on equal rights for all, implying reference to both women and men regardless of race, ethnicity, class, sex, ethnicity or religion. To date, only 34 countries have currently ratified the Charter, which shows hesitancy in closing the gender gap.

The Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (Maputo Protocol, 2003)

The Maputo Protocol (African Union 2003), adopted in 2003, incorporates provisions from the international human and women’s rights frameworks into the African context (see Box 2.1). The protocol contains specific provisions on women’s rights to participate in politics and decision making. These include taking measures to eliminate discrimination against women in elections and ensuring that women are represented equally in electoral processes and that they have equal opportunity to participate in political processes. It has taken two decades to have 42 countries ratify the protocol and the signatories are still at 49.

Box 2.1. Article IX: Right to participation in the political and decision-making process

- States Parties shall take specific positive action to promote participative governance and the equal participation of women in the political life of their countries through affirmative action, enabling national legislation and other measures to ensure that:

- Women participate without any discrimination in all elections;

- Women are represented equally at all levels with men in all electoral processes;

- Women are equal partners with men at all levels of development and implementation of state policies and development programmes;

- States Parties shall ensure increased and effective representation and participation of women at all levels of decision-making.

The African Union Gender Policy of 2009, the African Women’s Decade 2010–2020 and the African Union Strategy on Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment 2018–2028 have guided African Union member states to develop national gender policies and requisite strategies for their implementation. Most countries now have such policies and strategies in place. The challenge is in the slow pace of their implementation, although there are a few countries that have made significant progress towards gender equality and empowerment of women, including in the political arena, such as Lesotho, Mauritius, Mozambique, Rwanda, Seychelles and South Africa.

The African Youth Charter (2006)

The African Youth Charter was adopted on 2 July 2006 (African Union 2006). In its preamble, the Charter domesticates international frameworks, such as the UDHR, CEDAW, ICCPR and the ICESCR. It draws on the ACHPR and the Maputo Protocol (2003).

The African Youth Charter was motivated by concerns over the situation of African youth because they still faced numerous challenges, such as discrimination and marginalization from society because of their age, poverty, unemployment, low wages, lack of education and training opportunities, disease, hunger, and restricted access to health and other services. Youth are also involved in conflicts and other forms of violence. In article 11 of the Charter, there are several provisions to resolve those challenges. Member states are urged to take measures to ensure that youth, both women and men, enjoy full human rights and have equal opportunities for a healthy life, education and employment, so that they can live a life of dignity. Article 2(c) explicitly calls on member states to ensure that young women and men have equal access to participate in decision making and public affairs.

Article 23 is particularly important in relation to WPP as it specifies measures to promote the equal participation of young women and youth in politics (see Box 2.2).

Box 2.2. Article 23 of the Youth Charter: Girls and young women

1. States Parties acknowledge the need to eliminate discrimination against girls and young women according to obligations stipulated in various international, regional and national human rights conventions and instruments designed to protect and promote women’s rights. In this regard, they shall:

a) Introduce legislative measures that eliminate all forms of discrimination against girls and young women and ensure their human rights and fundamental freedoms;

b) Ensure that girls and young women are able to participate actively, equally and effectively with boys at all levels of social, educational, economic, political, cultural, civic life and leadership as well as scientific endeavours;

c) Institute programmes to make girls and young women aware of their rights and of opportunities to participate as equal members of society.

One of the challenges women face in politics is that most of them do not have adequate education or knowledge and awareness of politics in the public arena. Those who decide to go into politics often find that they are ill equipped for the task. Article 23 thus puts emphasis on treating boys and girls equally in terms of providing education and training. Consistent with CEDAW, the African Youth Charter calls on the African Union member states to take appropriate measures to prevent discrimination against girls and young women and to promote their active participation in all spheres of life. The emphasis is on instituting programmes to raise awareness among girls and young women of their rights and opportunities to participate as equal members of society.

African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance (2007)

The African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance (ACDEG) was adopted on 30 January 2007 (African Union 2007). It includes domesticated tenets from both the UDHR and CEDAW, as reflected in articles 1, 3, 6, 7 and 8. The ACDEG makes a call for strengthening political pluralism and recognizing the role, rights and responsibilities of legally constituted political parties, including opposition political parties, which should be given a status under national law. In line with the BDPA, it calls upon member states to take practical measures to increase the representation of women. In that regard, article 29 calls on countries to recognize the crucial roles played by women in development and in strengthening democracy, implement measures to support the full or active participation of women in decision-making processes at all levels, take measures to promote women’s participation in electoral processes and ensure gender parity in representation at all levels, including legislatures.

The African Union Gender Policy (2009)

In 2009 the African Union introduced its Gender Policy (African Union 2009), which calls upon member states to advocate the promotion of a gender-responsive environment and practices, to facilitate gender mainstreaming in institutions, legal frameworks, policies, programmes, strategic frameworks and plans. Countries are also called upon to develop and implement guidelines and standards for ending sexual and gender-based violence (GBV), take measures to remove barriers against the movement of people and promote equitable access for both women and men to control resources (objective 6).

Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want (2015)

Agenda 2063 is a continental long-term vision of Africa in which the aspirations of African people are laid out. Spearheaded by the African Union, Agenda 2063 aims to achieve peace, prosperity and inclusive and sustainable development for all the peoples on the continent (African Union Commission 2015) (see Table 2.2). It includes clauses that point to gender equality in decision making and politics in general terms. For example, it affirms the vision of the African Union to become ‘an integrated, prosperous and peaceful Africa, driven by its own citizens and representing a dynamic force in the international arena’ (African Union Commission 2015: 1). As indicated under Aspiration 6, the Agenda affirms the importance of women, youth and children, as the continent’s development relies on them.

| Article or aspiration | Provisions | Implications for women’s participation in politics |

|---|---|---|

| Article 49 | By 2063, women are empowered and play their rightful role in all spheres of life | Women have a right to participate in politics and leadership |

| Article 50 | The African woman will be fully empowered in all spheres, with equal social, political and economic rights, including the rights to own and inherit property, sign a contract, register and manage a business. Rural women will have access to productive assets, including land, credit, inputs and financial services | As above |

| Aspiration 6 | An Africa, whose development is people-driven, relying on the potential of African people, especially its women and youth, and caring for children. | The Agenda recognizes that women and youth have the potential to contribute to the continent’s development and the political arena. |

| Article 52 | Africa of 2063 will have full gender parity, with women occupying at least 50 per cent of elected public offices at all levels and half of managerial positions in the public and the private sectors. | This clause explicitly adopts full gender parity (50/50) in terms of the proportions of women and men in elected public offices. |

| Article 54 | The youth of Africa shall be socially, economically and politically empowered through the full implementation of the African Youth Charter. | This clause commits member states to empower youth. It refers to the African Youth Charter. |

2.3. Subregional level: Frameworks by regional economic communities

Africa is divided into eight subregional groupings of countries called RECs, which are subsidiary to the African Union. Their major role is to support countries in translating and implementing international and regional frameworks at the subregional level. Some of the RECs have started to implement the frameworks that have been developed in respect of women’s participation in politics.

A few RECs, notably the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the East African Community (EAC) and the SADC, have introduced frameworks that include some provisions for advancing women’s participation in decision making at all levels. Other RECs have introduced gender policies and strategies.

Economic Community of West African States

In May 2015 the ECOWAS heads of state adopted the Supplementary Act Relating to Equality of Rights Between Women and Men for Sustainable Development in the ECOWAS region (commonly referred to as the Supplementary Protocol; ECOWAS 2015). One of the eight objectives of the Act is to increase the rate of women’s participation at all levels of decision making across different sectors, including the political sphere, conflict prevention and management, and the restoration of peace and security. In February 2017 the Commission adopted a Roadmap for the implementation of the Act (ECOWAS 2017a). ECOWAS also designed a Gender and Election Strategic Framework (ECOWAS 2017b) designed to be more inclusive of women in political leadership.

The East African Community

The entry point for women’s rights promotion within the EAC is in the objectives of the EAC Treaty (article 5(3)(e)), which requires the EAC to ensure ‘the mainstreaming of gender in all its endeavours and the enhancement of the role of women in cultural, social, political, economic and technological development’ (EAC 1999: 13). Article 121 calls on member states to take measures to promote women’s participation in decision making and to prevent any discrimination against them. To operationalize the treaty, the EAC has enacted several acts and policies—the EAC Gender Equality and Development Act (2016) and the EAC Gender Policy (EAC 2018).

The EAC Legislative Assembly has also formulated the Gender Equality and Development Bill, which, at the time of writing, was awaiting assent from the heads of state. One of the objectives of the bill is to realize the EAC’s commitment to gender equality as set out in the EAC Treaty. One of the commitments is to prevent discrimination against women and to promote gender equality in the region.

Southern African Development Community: Protocol on Gender and Development (2008, amended 2016)

In 2008 the SADC Protocol on Gender and Development was adopted as the legal and policy framework for gender equality and women’s and girls’ rights. Six of its objectives focus on women’s and girls’ rights and gender equality, and it is cognizant of the 2003 Maputo Protocol. The SADC Protocol has some provisions on equal and effective representation of women in decision-making positions in the public and private sectors. It includes a call for member states to take special measures to advance these goals, and article 13 seeks to ensure that women have the same opportunity as men to participate in electoral processes. Apart from its binding nature, the SADC Protocol is unique in that it translates its provisions on women’s and girls’ rights and gender equality into 28 concrete targets that were to be reached by 2015. Botswana is the most recent country to ratify the Protocol (in May 2017), leaving Mauritius as the only country in the SADC that has not ratified it.

Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development