From Local Governance to Constitution Building

Yemen after 10 Years of Conflict

This report explores regional and local governance in Yemen and discusses prospects for a future constitutional framework following a decade of conflict between Ansar Allah, also known as the Huthi movement, and the internationally recognized government (IRG). Following a summary of relevant constitutional, political and institutional features of the Republic of Yemen since its establishment in 1990, the report outlines the main features of the Local Authority Law of 2000, which remains the main legal framework for local governance. It then briefly addresses the draft 2015 constitution, which followed the 2013–2014 National Dialogue, and the 2015 ‘Constitutional Declaration’ issued by Ansar Allah.

The report then focuses on the impact of the current conflict on governance in different parts of the country, paying particular attention to the formal and informal governance mechanisms at the district and governorate levels. To enable understanding of the complexities of the situation in which local governance is taking place, the report presents details of the competing political and military entities active in three governorates controlled by the IRG, Aden, Hadhramaut and Taiz.

Fragmentation and the now decade-long conflict have weakened the limited degree of decentralization provided for in the Local Authority Law: local governorate and district councils are no longer functioning. Governors are once again appointed by the country’s presidency and have increased their power including control over the limited funding available. The rivalry between competing elements of the IRG is reflected in the daily problems and difficulties faced by citizens, including with respect to the rule of law in the administration of justice or policing. Formal accountability to the citizenry is absent; however, popular views expressed through social media and frequent popular demonstrations in the main urban areas demonstrate the widespread dissatisfaction with the lack of basic services.

In both IRG- and Ansar Allah-controlled areas, community-level committees have become significant actors. These structures, although not part of formal state institutions, vary in influence, representativity and importance depending on both their origins, whether locally based or foreign funded, and their strength and ability to influence formal authorities.

The area under Ansar Allah control is discussed with regards to part of Taiz governorate. Its characteristics are similar to those elsewhere under Ansar Allah rule; it is characterized by a highly centralized system emanating from the capital Sana’a. Governorate-level institutions have very limited autonomy and their role is primarily to extract revenue from the people. Although state institutions still exist, in practice newly appointed local Ansar Allah supervisors have the power to overrule officials and Ansar Allah loyalists can act outside of the law and regulations with impunity. However, there are situations when Ansar Allah has been compelled to tolerate views and activities which are not fully aligned with its ideology.

The report concludes by pointing out that the fragmentation of the past decade has elements which could be positive for a future more democratic state. These include the increased powers and control at the governorate level which could expand beyond the role of governor towards stronger institutions. The re-emergence of community-based committees is an important development of people’s empowerment and an element which could be built upon to improve local governance and align it more with the needs and concerns of an overwhelmingly poor society. These could form positive elements in a better governed post-conflict future Yemen.

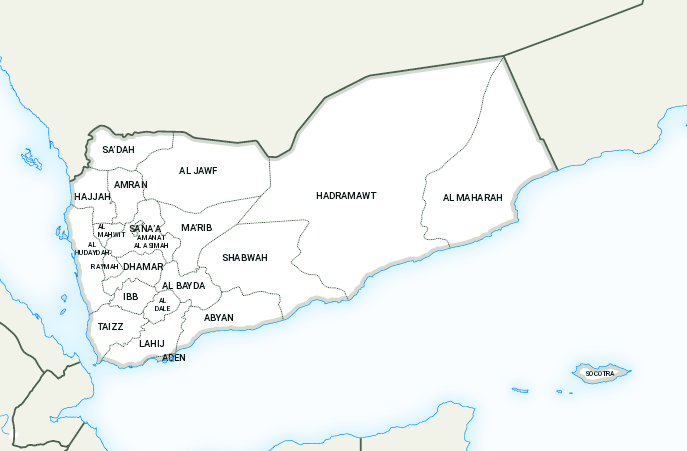

Ten years into the open conflict in Yemen between Ansar Allah (commonly known as the Huthi movement1) and the internationally recognized government (IRG), substate (including local) governance in Yemen has largely taken new forms, which differ from one area to another. Ansar Allah controls the capital Sana’a, as well as about 30 per cent of the country’s north-western territory, inhabited by about 70 per cent of the population, whereas the IRG has most of the land but far fewer people within its domain. As discussed below, the IRG is deeply divided into a multiplicity of factions.

This report discusses the different types of governance that exist in Yemen in 2025, and some of the issues concerning future constitutional aspects. It also addresses some of the analytical problems that affect countries in conflict at a time when, historically, they are becoming more numerous and varied in their statuses and management approaches, as well as in their national and international political contexts.

However, readers must be reminded that 10 years of war have had a fundamentally destructive impact on Yemen’s people, with one of the world’s worst food insecurity crises, leaving millions on the brink of famine. All basic services, from health to education and infrastructure, are badly damaged and the country suffers from a worsening environment, water scarcity being its most prominent issue. People’s dependence on international aid and remittances is now greater than ever and hopes for future improvements in their living standards are stymied by the absence of political resolution. In 2025, up to 20 million Yemenis are in need of humanitarian aid (WHO 2023).

Methodology

The field analysis for this report is based on four studies in different parts of Yemen: three in areas that are nominally controlled by the IRG but where different factions compete for control, and one in an Ansar Allah-controlled area.2 Alongside these, it uses several other relevant studies providing background information, as well as elements gained from other research work done in recent years. The author also benefited from half a century’s experience of working in rural development throughout Yemen, and on earlier analyses and writings. For this study, the author conducted remote informal interviews and personal exchanges with people living in different parts of the country.3

The study suffers from several constraints, particularly the author’s inability to conduct her own field work. In both Ansar Allah-controlled and most IRG-controlled areas, the expression of any views differing from official discourse is not tolerated. This has constrained the background papers as well as, of course, most conversations held remotely. While it can be argued that repression is most severe in areas under Ansar Allah, many of the factions involved in the IRG are also repressive. This is particularly the case for the Aden study as the city, while under nominal IRG control, is effectively controlled by the separatist Southern Transitional Council (STC), supported by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) regime. Although the STC is among the factions represented in the current Presidential Leadership Council (PLC), it makes little pretence of allowing the presence of organizations or individuals not explicitly aligned with its own separatist agenda.

This report starts with a brief outline of relevant aspects of basic developments in the Republic of Yemen (RoY) since unification in 1990, as they are relevant to understand the current political conflict as well as governance issues, particularly decentralization. The second part focuses on local governance, primarily using the four studies commissioned for this project, complemented by other studies and conversations, and attempts to understand the actual governance mechanisms of the different entities. The report then proceeds to identify the main lessons that should be learned from Yemen, and to consider the extent to which they are relevant to other countries. It then addresses prospects given the current uncertainty of the conflict’s outcome. Finally, it hints at potential options for the future.

1.1. Unification, the 1994 civil war and institutional governance changes

In 1990, the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR), with its capital Sana’a, and the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY), with its capital Aden, unified to form the RoY. With two ostensibly very different regimes, they were the only republics in the Arabian Peninsula. The YAR had been established by the overthrow of the royalist imamate regime in 1962 and the PDRY by the end of British control in 1967. Following armed conflicts in 1972 and 1979 between the two regimes, various committees were established towards a united Yemen, including one that drafted a joint constitution.

After unification, the Constitution was adjusted and approved by popular referendum in May 1991. From the beginning, tensions arose between the two former regimes’ leaders. President Ali Abdullah Saleh (hereinafter referred to as ‘Saleh’) was the dominant force in the political power struggle, both because the YAR had the largest population (about 8 million people) and because the former PDRY (population less than 3 million) socialist regime had been seriously weakened by the violent conflict of 1986. Despite significant democratic initiatives in the PDRY’s remaining four years, and the initial wave of democratic and free speech enthusiasm with the RoY’s creation, Saleh successfully undermined the Constitution’s democratic elements to bring about a regime where his rule would continue largely unchecked. This led to the 1994 short civil war between the Sana’a-based authorities and separatist elements under Vice President Ali Salem al-Beidh, which was decisively won by Saleh’s forces, partly laying the base for one of the country’s current conflicts.

The Constitution was modified to adjust to the post-1994 situation,4 with three main changes. First was the strengthened role of Islam, with the Constitution stating that ‘Islamic Shari’a is the source of all legislation’ (article 3), thus ending a very active debate between the Islamists and supporters of a more ‘secular’ constitution. Second, it established the Consultative Council (article 125), appointed by the president.5 The most important change was the cancellation of the Presidential Council, replaced by an elected president for a five-year term (article 107). Thanks to this, Saleh was elected twice, then changed the Constitution again in 2001 to allow a seven-year presidential term (article 112), which enabled his election once again in 2006.

Although the system was formally pluralistic, with several political parties continuing to operate, it was effectively autocratic, with power fully in the hands of the president, with no more than ‘a veneer of democratic institutions, mainly its two-chamber parliament which presented little legislative challenge to executive proposals’ (Lackner 2023b: 30). The parliamentary elections held in 1993, 1997 and 2003 were all organized to ensure the dominance of Saleh’s political organization, the General People’s Congress (GPC), allowing minimal space to its rival parties: the Islamist Islah Party, the Yemeni Socialist Party (YSP) which had ruled the PDRY, other small parties and some independents. When any party appeared to become powerful, particularly Islah, the regime took action to ensure the GPC remained dominant in the parliament.

The country’s political situation deteriorated over time, with a worsening economy as diminishing oil revenues reduced the regime’s ability to pacify the population with patronage. Poverty worsened, affecting more and more people, and the population became increasingly frustrated with the regime’s close control over resources and obstruction of all efforts to bring about democratic change. Tensions arose, most visibly manifested by the rise of the Huthi movement in the country’s far north, and its six wars against the Saleh regime between 2004 and 2010, the rise of southern separatism from 2007 onwards, and the worsening tensions between Saleh’s GPC and the formal opposition, focused on succession to the presidency. These factors combined with others to bring about the 2011 uprisings, ignited by Saleh’s new attempt to change the Constitution to enable him to stand for election yet again, as well as the uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt.

1.2. Decentralization: A focus for political struggle

From 1990 onwards, political struggle focused on the issue of decentralization in the form of discussions on local governance. In the negotiations for unification, the Aden-based YSP had strongly argued for the creation of a federal state, which would enable significant autonomy in domestic policies, including survival of the socialist regime’s social benefits for the population. The complete merger that took place was widely believed to be a unilateral and unapproved decision made privately by

A range of local government laws were debated in the GPC-controlled Council of Representatives (the parliament). Those supporting a high level of decentralization and authority for local governance saw this as a mechanism to reduce the nepotistic regime’s power, and to increase authority over management of affairs at the governorate and district levels. Unsurprisingly, given the balance of power, the Local Authority Law (No. 4) passed in 2000 retained a strong element of centralization, giving local authorities numerous responsibilities without the means to implement them, as the resources to which they had access were insignificant, with the notable exception of taxation on qat. In response to increasing dissatisfaction throughout the country, the only significant concession made was the amendment (Law No. 18 of 2008) that changed the mechanism for the selection of governors, who would thereafter be elected by local council members; as a result, most later governors were themselves civilians from the governorates rather than military appointees, though many district officials were from security agencies, as had been the case before.

Local elections were held in 2001 and 2006. They were both strongly contested, and saw significantly higher levels of violence than the national parliamentary elections. This demonstrates their importance and the strength of competition between rival local elites.

1.3. The road to war: The 2011 uprising and the 2012–2014 transitional government

While open discontent and demonstrations had been building up over the years, the events of 2011 in Tunisia and Egypt gave Yemenis the perception that regime change was possible. Therefore, from January onwards, demonstrations increased throughout the country. Following a split within the regime between supporters of Saleh and Islah who joined the demonstrations from March onwards, military clashes between the factions played a major part in developments from then until November, when the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) agreement was signed in Riyadh. This led to Saleh giving up the presidency and his vice president, Abdo Rabbo Mansour Hadi, a southerner, being elected as president in an unopposed election in February 2012, to lead what was supposed to be a two-year transition to a more representative regime.

Supposedly supported by the ‘international community’ in the form of a committee of 10 ambassadors (the GCC, several European countries, the European Union, the United States) the transition was to include a Government of National Unity, a security sector reform, a National Dialogue Conference (NDC) to agree on the country’s future, and the preparation of a new constitution if necessary.6 Today, some would argue that it was doomed to fail: the security sector reform, which was directly supported by the USA, took place simultaneously with the other processes, and it failed to provide an effective security sector able to enforce government decisions. The Government of National Unity was 50 per cent composed of Saleh’s GPC, reflecting his continued influence, and 50 per cent composed of competing political parties from the formal opposition, the Joint Meeting Parties, alongside the ‘new forces’ of 2011, women, youth and civil society. It promptly gained a reputation for unparalleled incompetence and corruption (IRIN 2014).

The NDC, lasting 10 months, failed to solve the most pressing state structural issues, namely those of southern separatism and the Huthi demands for powerful positions in government. Its ‘outcomes’ were officially meant to guide the drafting of the new constitution by a separate committee. One of the main agreements within the NDC was that Yemen should become a federal state, though the details were a source of strong disagreement. A later presidential committee announced a six-region federation, which was immediately rejected by the Huthis, who stated: ‘We have rejected it because it divides Yemen into poor and wealthy regions’ (Lackner 2016: 47). The decision on the regions was politically expedient and unrelated to the criteria that should determine such a decision, such as population balance, social cohesion, natural resources (particularly water, given its scarcity in Yemen) and economic potential.

During the official two years of the transition, the Huthis consolidated their positions in the far north of the country and gradually expanded southwards, increasing the areas under their administrative control. At the same time, they started to cooperate with their former enemy, ex-President Saleh, who had his own reasons for undermining the transition. Both groups shared an opposition to federalism, one of the major proposals for the country’s future. By September 2014, due to the government’s weakness and thanks to support from Saleh’s security forces, the Huthis took over the capital Sana’a without a fight.

The finalization and official submission of the draft constitution in early 2015 was the trigger for the Huthis’ takeover of state institutions. Within weeks, it led to full-scale fighting in the country, and to the IRG’s transfer to Aden as a ‘temporary’ capital. As the Huthi-Saleh forces moved southwards and attacked Aden, Hadi escaped and called for international military intervention from Saudi Arabia and the GCC countries. On 26 March 2015, a Saudi-led coalition launched ‘Operation Decisive Storm’ to return the Hadi government to power. Saudi Arabia’s military involvement was primarily through airstrikes, while the UAE deployed significant national and contracted ground troops.

1.4. Context since the 2015 war

Within the first weeks of the war, the Huthi-Saleh forces reached Aden, but were repelled in July 2015. In 2018, IRG forces, supported mainly by UAE leadership and with thousands of Sudanese ground troops, reached the southern part of Hodeida, intending a major offensive to take the city in a strategy that assumed losing Hodeida would force the Huthis to negotiate. Fearing that close urban warfare would cause massive casualties, and the potential impact of the Hodeida port’s closure on the humanitarian crisis, the United Nations and other international supporters of the coalition forced the interruption of the offensive. In December, this was followed by peace discussions in Sweden between the Huthis and the IRG, which led to an agreement whereby all military forces would be withdrawn from Hodeida, and port revenues would be used to finance payment of civil servants’ salaries. This agreement was never fully implemented. From 2018 to 2021, the anti-Huthi forces held the southern Tihama coastal plain, including the southern part of Hodeida city. They then withdrew about 100 km southwards to reinforce the defence of Marib which was facing a strong Huthi offensive, leaving that part of the Tihama under Huthi control. This remains the situation in early 2025. Since then, ground fighting has been limited, and there have been no significant changes in control. In April 2022, a truce was agreed, which officially lasted until October. Although fighting between different Yemeni forces has continued at a low level on all main fronts since then, there have been no air strikes by Saudi and Emirati forces. The ‘truce’ is widely described as still being in place, however informally.

UN-mediated peace negotiations between the IRG and Ansar Allah took place in 2015, 2016 and 2018. Throughout, the Huthis have asserted that they are fighting the ‘foreign occupiers’, Saudi Arabia in particular, and that the IRG are mere ‘mercenaries’ to the Saudis and Emiratis. Since 2021, significant negotiations have taken place between the Huthis and Saudi Arabia and, in 2023, were close to finalization when Huthi involvement in the Gaza war prevented their conclusion.

Outline of the proposed Saudi–Ansar Allah agreement

Given its relevance for the future, outlining the proposed Saudi–Huthi agreement is important. After nine years, the Saudi regime was fully determined to extricate itself from the war in Yemen, and has taken no military action against the Huthis since April 2022, other than defensive small-scale interventions against cross-border Huthi attacks. The Saudis want the deal to be formally between the IRG and Ansar Allah, allowing them to feature as mediators rather than a party to the conflict. The agreement would include a complete ceasefire and no cross-border attacks, thus securing Saudi Arabia’s territory.

Given their strength on the ground and their military control, the Huthis made few concessions: Saudi Arabia apparently agreed to pay the salaries of all Yemeni government staff, including Huthi military and security personnel, for at least one year. IRG oil exports (interrupted by Huthi attacks on exporting ports in October 2022) would resume, and Saudi Arabia would finance an aid package for reconstruction. If the draft Saudi–Huthi agreement was finalized, the UN Special Envoy and his team would be given the responsibility of mediating a Yemeni–Yemeni agreement between the Huthis and their opponents. As this would take place within the context of overwhelming Huthi superiority, the likelihood of achieving an equitable and sustainable peace would be low.

Negotiations were effectively suspended with the initiation of Ansar Allah’s active involvement in military actions in support of Palestine in October 2023. The January 2025 Gaza ceasefire agreement halted all activities which resumed on 17 March despite the massive US air onslaught on Yemen which started on 15 March

1.5. Current socio-economic-political situation

As mentioned in the introduction, Ansar Allah controls the capital Sana’a, about one-third of the country’s territory and 70 per cent of its population. The rest of the country is officially under the IRG’s authority. Until April 2022, the IRG, led by President Abdo Rabbo Mansour Hadi, suffered from considerable internal divisions, with various military factions run by elements with competing political and military objectives. In April 2022, within days of the truce and in hope of creating an effective presidency, the Saudis and Emiratis forcibly replaced Hadi with the PLC7 of eight men, four each aligned respectively with Saudi Arabia and the UAE, whose objectives and strategies have increasingly diverged since 2018, even leading to occasional clashes between the Yemeni factions close to either of these countries. Most PLC members lead their own military units, largely financed by the Saudis and the Emiratis, respectively.

Since its creation, the PLC has failed to act as a united anti-Huthi entity; the rivalries between its members and their forces have taken priority. The IRG is seriously short of funds: its primary source of national income, hydrocarbon exports, has been interrupted by Huthi actions since October 2022. This leaves it with limited international assistance, customs and other duties, as well as taxation—all of which are far from providing the funds for basic payment of recurrent costs such as salaries, let alone socio-economic investments. Support from Saudi Arabia and the UAE is systematically delayed, keeping the government waiting and unable to pay salaries, or to maintain basic services such as electricity and water in the cities.8

Overall, the economy has seriously deteriorated: the gross domestic product has dropped by 54 per cent (World Bank 2024: vii) since 2015. Within the realm of the PLC/IRG, the economic situation varies from one area to another, depending on local resources and the quality of governance. IRG revenues dropped by 42 per cent in the first half of 2024, following a drop of 50 per cent in 2023 (World Bank 2024: vii). Little revenue comes to the central government, as governors tend to keep revenue for their own coffers, whether for legitimate use or not. This is particularly the case in the ‘temporary’ capital, Aden, where the IRG is largely dependent on the goodwill of the STC,9 a group that controls the city and whose prime objective is to return to the pre-1990 borders and accessorily to undermine the IRG. Governorates with significant hydrocarbon resources (Marib and Hadhramaut) take some production revenues (when they exist) for their own use, though officially they are only entitled to 20 per cent of hydrocarbon revenues following an agreement reached in 2013. Other governorates without significant resources put as much pressure as possible on the IRG in hopes of receiving the funds needed, as is the case in Taiz, where demonstrations in demand of salaries are frequent.

Fragmentation is not only geographical and administrative, but also social and political. Although the population cannot be assumed to support the governors or military leaders in control of their areas, people are dependent on their goodwill for access to the limited support available. Even access to humanitarian assistance is not exclusively based on need and objective criteria, with local leaders having significant influence on distribution of cash and goods.

For a better understanding of the overall political situation, other forms of social fragmentation must be considered, as they are part of the Yemeni polity and, in some cases, have considerably intensified over recent decades, particularly since the open conflict started in 2015. While ethnically cohesive, Yemen has significant social differentiation between most of the population, who are tribespeople and whose allegiance is primarily to their tribes, thus creating a patchwork of different tribal groupings. Other than tribes,10 there are also low-status social groups as well as higher-status ones, such as the sada (the Yemeni term for descendants of the prophet, elsewhere known as Hashemites or ashraf). The Huthi leadership belongs to this latter group, which is given significant privileges in the areas under Ansar Allah rule. The Yemeni social structure has some similarities with the South Asian caste system.

In recent decades, allegiance to formal political parties has become another mechanism for social cohesion, or further fragmentation, depending on interpretation. Often overlapping with tribal allegiance, it can also allow people to mark a break with tribal mechanisms, by creating competing poles for allegiances. Professional and other shared interest associations are a further source of alignment and solidarity. Finally, the current fragmentation is worsened by sectarianism between the Zaydi Shi’a population (whether Huthi or traditional) in the far north and the Shafi’i Sunni population elsewhere (with Salafi and Muslim Brotherhood movements); much of this fragmentation is manifested in the various military units operating under different leaderships, whether part of state-sponsored armies or not. The overlap of these different allegiances can create confusion. It is particularly important to be aware that governorate borders do not define specific groupings or identities.

One example of competition for ‘political legitimacy’ between the two sides is the situation of the Yemeni House of Representatives (parliament). Both Ansar Allah and the IRG use the 1991 Constitution, and neither refers to changes in this fundamental institution in their rhetoric or daily political practice, regardless of both the 2015 draft constitution and Ansar Allah’s 2015 ‘Constitutional Declaration’. In Sana’a, the parliament that meets regularly in the House of Representatives building is headed by the Speaker from the Saleh period, and partial elections were held to replace deceased members in 2019. By contrast, the members of the parliament aligned with the IRG have a new speaker but no formal meeting place, and have held only two meetings; the STC has prevented the parliament from meeting in Aden, demonstrating its control over the city. It met once, in Seiyun, in April 2019 within days of Ansar Allah’s by-elections for 24 vacant seats (Abdo 2019). The only other meeting to date was a half-day one in Aden in April 2022 to formally recognize the PLC, when members were flown into and out of Aden by the Saudis for the event. Despite Saudi efforts to assist in holding another meeting in 2024 to endorse the new government appointed in February 2024, none had been held by March 2025.

The 1991 Constitution, amended in 1994, remains the country’s operational constitution, regardless of being partly superseded, and largely ignored and disrespected by most political forces. More recent documents, which are all ignored, include the 2011 GCC agreement, which asserts that it supersedes the Constitution and other institutions of the state (Lackner 2016: 73) and the 2015 draft constitution, which was never adopted. Other than being the justification for establishing the Supreme Revolutionary Committee, the 2015 Ansar Allah Constitutional Declaration (Revolutionary Committee of the 21 September Revolution 2015) asserts that the 1991 Constitution remains in force. Given this situation, focusing on the 1991 Constitution seems appropriate. However, it is worth noting that the lack of respect for the Constitution and the rule of law is a major cause of the current continued lawlessness. The 1991 Constitution has little interest in local government, and the articles on the topic, as outlined in Annex A, are remarkably vague. Perhaps most significant is the emphatic statement in article 147 that decisions of the president and Council of Ministers bind all local administrative bodies, which is carried through in the laws on local administration. Other legal frameworks (partly) dealing with local government are summarized below.

2.1. The Local Authority Law (No. 4 of 2000)

The law discusses rights and responsibilities at two levels: that of the 22 governorates, the largest local administrative units existing in the country, and that of the 333 districts. The following state institutions are explicitly excluded from the Local Authority Law: judicial institutions, the armed forces and the Central Organization for Control and Auditing, in addition to a ‘catch all’ option that excludes ‘any utilities of a public nature at the national level that are determined by promulgation of a Republican decree’ (article 3d). To compensate for this rather broad exclusion, article 4 states that ‘the local authority system is based on the principle of administrative and financial decentralization, and on the basis of expansion of popular participation in decision making and management of the local concern in the spheres of economic, social and cultural development’. Officials of local councils, at either the district or governorate level, are elected for a term of four years, renewable once. The law also goes into detail on standard democratic mechanisms. Districts and governorates are to have their own planning and budgets.

At the governorate level, the council includes at least 15 members, elected by the citizens at the rate of one member per district council, with additional members if there are not enough district councils (article 16). Its role is to study plans and supervise their implementation (article 19), and to supervise the work of the district councils and the executive organs of the governorate (article 19). An elected general secretary must be aged 35 or over, with university education and at least five years’ experience in administration (articles 20 and 21). His duties are to ‘assist the Governor in the management of the affairs of [the] local council’ (article 22). Governorate local councils are to meet at least once every three months (article 24). Local councils at the governorate level have a management committee composed of the chair, the general secretary and the heads of specialist committees (article 31).

The governor has ministerial rank and is appointed by republican decree on nomination of the minister after approval by the Council of Ministers (article 38). His term of office is four years, and he chairs the local council. He is accountable before the president of the republic (article 40). As discussed above, this was modified by Law No. 18 of 2008 so that governors were later elected by secret ballot by the members of the governorate local council. The governor must either reside in the governorate or originate from it. There is no suggestion that a governor might be female. After the change in the selection process, most governors were civilians and natives of their governorates.

Governors represent the state, chair all major meetings, are the heads of the civil servants in the governorate (article 43), report to the minister (either for local government or of the interior, though this is not stated), and have the general secretary as their deputy (article 47). Executive offices of the governorate include the governor, the general secretary, the governorate undersecretary and directors of executive organs of the governorate (article 52).

At the district level, the council’s size depends on the population (article 59). It drafts social and economic plans, approves budgets, determines fees for local services and so on (article 61). District councils have multiple responsibilities and little power: one indication of this is the statement that, if selection criteria are not met, the district council secretary general is to be appointed by the Council of Ministers rather than even the governor (article 63b). This may be a remnant of the fact that the governor was previously appointed by decree, after approval from the Council of Ministers. Only three committees operate at the district level: the planning, development and finance committee, the services committee and the social affairs committee (article 65). Here again, executive authority is out of the hands of local people, a situation shared with many other Arab countries. The district general director is appointed by a resolution of the prime minister upon the nomination of the minister (article 81) and ‘is the senior executive official’ (article 82). Districts have executive offices composed of the general director, the general secretary of the council and the directors of executive organs in the district (article 91).

As explained by the law itself, and confirmed in the case studies on Aden, Hadhramaut and Taiz, ‘the law effectively granted the central government veto power over their decisions … the president appointed the governors and the heads of districts were elected by the central government, leaving local councils with minimal authority. … Members of the executive offices were accountable to local councils under the local Authority Law, … [but] they functioned as extensions of the central ministries within the governorate and districts, being appointed and their salaries paid by the line ministries. … Their primary allegiance was to the line ministries’ (Basalma 2024: 2).

Financial resources determine the ability of local councils at all levels to initiate activities, and even to implement decisions made elsewhere. Therefore, discretionary funds available to them are the fundamental indicator of their actual relevance and power. As evident from the sources of local finance, discretionary funds are very limited. The main income is grants from the centre, thus giving the capital effective control over supposedly decentralized governorates and districts.

At the district level, article 123 lists 27 sources of finance, most of them insignificant or non-existent, including advertising fees, cinema and other entertainment taxes, and parking fees. Others are clearly unable to cover the kind of expenses and plans that local authorities might want to implement, including fees for building permits, borehole drilling, slaughter houses, animal and plant vaccinations, and registration for a variety of activities. The only significant source is 50 per cent of zakat11 revenue.

Governorate-level taxes are obviously collected at the district level, and include the other 50 per cent of zakat, which is significant, as well as the qat consumption tax. The remaining 25 sources of finance in the list are fees for medical, economic, health and administrative services, and are unlikely to amount to much.

Governorate and district councils are to share fees on air and sea travel tickets, and on each barrel of oil or gas sold, as well as 30 per cent of the annual revenues of the Road Maintenance Fund, the Agriculture and Fisheries Production Promotion Fund, and the Youth Care and Sports Fund. In addition, they receive ‘that which is allocated by the state from annual central financial subsidies to the administrative units at the level of the Republic’.

According to article 124, other resources are to be distributed and redistributed equitably within the units—the district or governorate collecting the tax—according to population density, resources, growth and deprivation, and competence of the authority’s performance. These praiseworthy statements are somewhat undermined by article 127, which asserts: ‘the offices of the Ministry of Finance and revenue authorities subordinated to them shall not be subject to the supervision of the local councils, except in respect of central resources’.

In practice, local authorities at all levels were primarily dependent on the central government for financial resources prior to the current war. In 2014, 90 to 95 per cent of local council funds came from the central government (al-Awalaqi and al-Madhaji 2018: 28). Since then, the central government in the IRG has struggled to get any funding, while Ansar Allah has collected taxes but done little redistribution, as discussed below.

2.2. The 2015 draft constitution

The 2012–2014 transitional process included the drafting of a new constitution. This took place throughout 2014 and was ultimately the trigger for the Huthi overthrow of the regime. The Constitutional Drafting Committee finalized the draft in December 2014 and was due to submit it to the relevant parliamentary committee in January 2015, an event prevented by the Huthis’ kidnapping of the president’s emissary as he was en route to the meeting. As it emerged indirectly from a wide-ranging national dialogue, and contains constructive elements that might be relevant in the future, a summary of the draft’s main elements concerning local governance is relevant.

Containing 446 articles, the draft was the outcome of debates between jurists over many months, and reflected their failure to agree on many points, leading to much duplication of statements of principle. While it gives considerable detail about selection processes for the different regional and wilaya (governorate)-level political procedures, it includes few details on the type of federal system to be enacted, and particularly on the distribution of resources and extent of authority of the different levels of the state. Given the uneven distribution of natural resources in the country, particularly of water and hydrocarbons, these are issues which should have received far more attention (Zulueta-Fülscher and Murray 2024).

By contrast, the draft details the geographical coverage of the six regions (to be established) determined by the presidential committee which selected the governorates composing them. In other words, it is simply based on the administrative status quo, rather than addressing fundamental issues that should determine such a distribution. It contains detailed procedures on elected institutions, but is very weak on funding, in terms of both sources and their distribution among different levels, other than mentioning the need for equity. Overall, it really indicates that those drafting it focused on short-term and historic political struggles rather than the actual needs of the population for a workable constitution. Given the circumstances, whether it could have done any better is debatable.

2.3. Ansar Allah’s Constitutional Declaration

On 6 February 2015, a few weeks after taking over the capital Sana’a, Ansar Allah published a ‘Constitutional Declaration’. This is a short document that focuses on ‘the rules of governance within the transitional stage’ (article 2) without clearly specifying either the nature or the duration of the transition. While it is often considered as superseding the constitution, this is not the whole story. The Constitutional Declaration assumes that its determination of what parts of the 1991 Constitution are still operative is binding, thus asserting its precedence, but chooses to retain most of the old constitution and existing law, thus including, of course, laws pertaining to local administrations. Article 1 states: ‘the provisions of the Constitution shall remain in force insofar as it does not expressly contradict or be in conflict with this decree’; and article 14 asserts that ‘all ordinary legislation shall remain in force unless inconsistent with the terms of this decree’.

Ansar Allah created a Supreme Revolutionary Committee with branches at the local level, specifically mentioning ‘governorates and districts’ (article 5) that would appoint a government. According to article 6, the Constitutional Declaration would replace the parliament with a Transitional National Council of 551 members and create a Presidential Council of five members (article 8). However, like many other proclamations by both the Huthis and the IRG, much of this was not implemented. It also claimed that ‘within two years’ the Transitional National Council would implement the recommendations of the NDC, as well as those of the Peace and National Partnership Agreement12 ‘including a review of the draft constitution, the enactment of laws and the holding of a constitutional referendum’ (article 13). Other than this, it does not mention local governance.

3.1. Introduction

The four field studies conducted for this report cover three main locations —Aden, Hadhramaut and Taiz. A summary is first presented of the overall governance and political situations of the areas studied, as this is indicative of the situations’ complexities.

Aden is officially the ‘interim’ capital of the country and has been the seat of the IRG since 2015. However, as noted above, in practice, it is the main stronghold of the STC, an organization whose entire rationale is based on returning the country to its pre-1990 borders, and thereafter to rule the area of the former PDRY. There are intermittent smaller or larger conflicts between IRG and STC elements, and there have even been times when the STC prevented ‘northern’ IRG leaders and ministers from visiting the city. With respect to daily life, most national ministers of southern origin can operate freely, particularly if they subscribe to the STC agenda. Local governance in the city is primarily under the STC, which also successfully retains at least some revenues from port fees, customs and other sources, often defying the law and further worsening the IRG’s overall financial situation. The paucity of services, and the constant crises in electricity supply and other basic utilities, are widely seen by the population as the responsibility of the STC, which firmly denies any involvement and shifts the blame to the IRG, despite the latter’s lack of influence on daily life in the city. Assessing the actual situation of local government in Aden is complex.

Taiz Governorate presents even greater complexity: not only is it divided between areas under Ansar Allah and IRG control, but areas under the IRG are also affected by the rival influences of far more entities, whose alignment with the IRG as an institution is debatable. Taiz has a long history of popular involvement in politics and in community affairs, and may be unique in having a strong presence of various political parties whose membership is primarily based on ideological commitment rather than personal or ascribed group membership. Although none of the factions are separatist like the STC in Aden, the parties represented include Islah (associated with Muslim Brotherhood ideology), the YSP (former governing party of the PDRY), the GPC (former ruling organization of the unified state) and Salafi movements (more radical Islamists than Islah, with occasional connections with jihadis).

Hadhramaut, in the east of the country, is the largest governorate geographically (and one of the wealthiest), but its population is only about 2 million people. Historically, its relationship with both Aden and Sana’a as capitals has been distant; its people perceive themselves to have a strong, specific identity. Most Hadhramis regard their relationship with Saudi Arabia (due to lasting migration) and other regions (such as Southeast Asia or East Africa) as at least as important as that with the Yemeni state. Their allegiances are primarily to Hadhramaut, and Hadhramis generally, at best, want an arm’s-length relationship with any Yemeni state, but are likely to choose independence rather than a subordinate relationship with a Yemeni capital. This is currently most visible in the fact that the different groups’ allegiances to the IRG, STC and international sponsors remain unclear regardless of their titles. The governorate is geographically, and to a lesser extent socially, divided between the wadi and Sahra (valley and desert) interior,13 with Seiyun as its capital, and the coast, with its capital Mukalla. Tribes have taken a dominant political role in recent decades, displacing both the lower-status groups and the high status sada, who were dominant in the PDRY and the British colonial period, respectively.

The differences between the three areas under the IRG are merely illustrative of the range and variety of situations found. Other governorates have their own specificities, which contribute to the overall complexity of the situation, further marked by the dominant political/military leaderships involved in each area.

By contrast with the IRG situation, Ansar Allah local governance is extremely centralized. As a result, although Taiz is our only detailed example, it can be considered reasonably representative of the overall type of governance, even though it has its own socio-economic circumstances and, unlike much of Ansar Allah territory, is not part of the country’s Zaydi heartland.

3.2. Internationally recognized government: Fragmentation

The case studies are mostly urban and focus on local governance, rather than the role of the central government; as is the case throughout the IRG, different rival groupings are in charge in each area. In Aden, there is a single rival to the IRG—the STC—competing with the IRG central administration for revenues and authority. In Taiz, the competition is between different factions of the IRG, without a single faction wielding dominance. Hadhramaut is affected by the fundamental divisions within the IRG, with some groupings closer to the IRG and Saudi Arabia, and others closer to the STC and the UAE; though again, it is notable that Hadhrami loyalties are fundamentally focused on Hadhramaut. Despite rising tensions in recent years, Hadhramis have avoided coming into internecine armed conflict.

By contrast, the presence of rival groupings in both Aden and Taiz has led to active insecurity, with frequent armed clashes between rival groups and a lack of basic security for citizens. In the mid-2020s Aden residents must contend with more than 30 competing armed groups operating in the city. In Taiz, there are at least three main ones (Salafis, connected to al-Qaeda, and Tareq Saleh’s14 National Resistance Forces). Both sites have ‘official’ security committees, which are supposed to coordinate issues of national security between different institutions at the governorate level, but in neither Aden nor Taiz do these committees have the authority or ability to address conflicts between rival factions, and they do not address issues of basic policing. In Hadhramaut, there are military units aligned with the IRG and the Saudis (the 1st Military Region based in Seiyun in the wadi), and those closer to the STC and the UAE (the Hadhrami Elite Force), as well as the 2nd Military Region based in Mukalla, while tribally based units are primarily loyal to the local tribal leaders.

Given this context, the police take a secondary role in daily safety for citizens. This is worsened by the fact that in many situations, the police take no action unless their ‘expenses’ are paid by the person complaining. This situation is by no means new and has prevailed for decades, affecting people’s perception of the police and formal institutions’ willingness to achieve justice or redress. As explained in the Taiz study, ‘police stations charge for routine services’ (Al-iriani 2024: 19), with charges covering costs for the service provision. This is a further reason why citizens prefer to solve their problems via informal/unofficial mediators or influential people.

Elected bodies: The local councils

In Aden, Hadhramaut and Taiz, the local councils elected prior to the conflict have effectively ceased to operate in the sense of holding meetings and taking decisions. This is due to the changed political conditions and tensions between different groups.15 However, councillors still consider themselves representatives of their electorate, as do many residents. Thus, their influence depends on their personalities, and the extent to which people call upon them when they have issues with each other or with administrations; that is, they have simply become local ‘notables’. In some cases, they had been elected to the councils precisely because they were already locally influential; others acquired status through their performance. Insofar as some of the formal institutions still operate, for example, in some districts in Aden, the individuals heading the three main committees (planning, social affairs and services) are still in place, but are not particularly active.

Administratively, civil servants carry out their responsibilities to varying extents, depending on both personal commitment and the extent to which they are paid, something which, again, is also variable. New appointments are politically motivated, with leaders appointing individuals who are supported by the more powerful political groupings in the area. At the district level in Mudhaffar, Taiz, the director of the council ‘implements a miniaturised version of the political quota system used at the governorate level but appoints civil servants from two more parties, including the Nasserist and Socialist parties, at his discretion’ (Al-iriani 2024: 13).

In Aden, the multiplicity of appointees, particularly at the deputy governor level, leads to competition between the 22 incumbents and reduces efficiency even further. As is the case in Taiz, ‘political dynamics play a significant role in the appointment of officials within the local authority … the STC appears to exert influence over the selection of district’ senior officials (Basalma 2024: 3).

The governors

The mechanism introduced in 2008 for governors to be elected by local councils is no longer used, with all governors now appointed by the president. This means the only element of decentralization and partial democratization that existed prior to the war has simply ceased to function. Appointees are from their own governorates, though once again, they are often military cadres. They have also become far more powerful, particularly in Hadhramaut and Marib, where they control significant financial resources. Governors mostly appoint other senior officials, again largely without consultation of the non-operational councils or, indeed, anyone else. However, powerful military leaders and other (socially or religiously) very influential persons have a say in appointments of civil servants.

Revenue collection and financial management

The main source of income at the governorate level is still, despite its constraints, the central government based in Aden. All governorates need it to pay salaries, which are their main current expenditure item. Taxation revenue is from customs, port fees and taxes on businesses. In Hadhramaut, port and business taxation is significant, and some of Taiz’s districts are among the country’s wealthier and more productive ones thanks to the presence of many factories. Additionally, qat is an important resource everywhere, particularly as most of it remains at the local district level rather than going to the central coffers.

Businesses pay taxes, though in some cases there are ‘negotiations’ with tax collectors at the local level. Particularly in Hadhramaut, people cannot conduct many activities unless they produce an up-to-date ‘tax card’, which is a unique tax identification document. The tax card is required to renew business licences and other services in public institutions, so eventually businesses must pay to continue operating. Tax collectors in Taiz have been reported to harass those who do not pay (Al-iriani 2024: 15). Unlike in some other areas, local financial staff pay funds into the Central Bank. In some cases in Taiz, this includes funds that should be reallocated for use at the governorate level: a 25 per cent portion of revenues collected within a district should be (but is not) returned to the district. The district pays about YER 100 million monthly to the Central Bank, retaining YER 50 million. In view of the insufficient funds provided by the central government, and despite the retention of some of those funds, district staff still have great difficulties in paying for services.

Despite the STC’s dominance, Aden local authorities are also struggling to finance their operations. Central government financing of local authorities effectively stopped in 2015. An ad hoc agreement was reached between the STC and the IRG, whereby local authorities would take 20 per cent of the value of local projects implemented by international organizations. In 2022, the governor of Aden created the Centre for Developing Financial Resources. Designed to increase local revenues, it brought 53 collecting offices into a single system, and has increased collected revenues from YER 2 billion to YER 15 billion between 2022 and 2024. However, revenue from qat taxation is a mere YER 6 million daily, a very low amount given the amount of qat consumed. Most tax income likely goes directly to the STC (Basalma 2024).

It is unclear to what extent revenues intended for the IRG are indeed paid, and how much is held back by the STC, either institutionally or for private benefit. In Aden, salaries are paid intermittently, as is the case elsewhere, and in 2023 educational operational costs amounted to YER 3 billion for schools, including teacher salaries. For example, to avoid paying port fees to the central government, the STC has built its own small port west of Aden, to which it diverts many smaller incoming ships, mainly those coming from the Horn of Africa. The income from this port is exclusively for the benefit of the STC and, by extension, further weakens government finances.

Throughout the IRG area, the shortage of government financing means that most infrastructure and other projects, large and small, are funded by international financiers such as the World Bank, the Saudi Development and Reconstruction Program for Yemen, Germany, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and, previously, the USA. Visits by the president of the PLC, or his vice presidents, are reminiscent of Saleh’s in earlier decades, with promises of funding for myriad long-awaited development or infrastructure projects. The extent to which they materialize is a different story.

Community committees

Community-level involvement in politics and administration has been a major form of popular participation in Yemen for many decades. In the 1960s and 1970s, migrants set up associations to support their own communities by financing basic facilities such as schools, medical centres and roads.16 These became the formal Local Development Associations in the 1970s and were transformed by Saleh into the local administration, shifting the initiative from communities to the state. In the 1990s, there was a form of return to community involvement through various externally funded projects that demanded ‘community participation’ in the shape of material contributions and post-construction management—paternalistic strategies that gave very little power or autonomy to these groupings, and were widely perceived as foreign impositions rather than expressions of local concerns.

With the war and the increasing absence of state funding and administration, as well as dormant local councils, community committees have re-emerged. They are now important actors in both addressing local problems and politics, and managing funding or support for local services. Unsurprisingly, their quality, representativity and performance covers the full range from excellent to abysmal. The involvement of foreign financiers varies, and affects the performance, responsibilities and credibility of these committees.

In Aden, there are numerous committees, some established in 2021 by the governor, the main role of which is to ‘assist international NGOs and the local authorities in the planning process by providing a data base from the neighbourhoods, such as the number of IDPs [internally displaced persons]’. These committees also present the advantage of being unpaid volunteers. International funding has supported the training of their staff, and played a useful role in improving their skills, but has also limited membership to those involved with a project. Some of these committees, which included civil society representatives, developed into ‘mediation committees’. The latter, while limited to Aden, operate from the offices of local authorities and are active in dealing with prisoners and other community mediation issues. Their role is limited to mediation of conflict (Basalma 2024).

In Hadhramaut, community committees appear to be operating effectively both to address problems and to represent their members in interaction with state institutions, from the governor onwards. They also deal with any external funding and projects, where they provide grassroots monitoring. In the major cities at least, they are an impressive form of community management and could well become the base for a more democratic polity at the governorate level.

Civil society involvement and community accountability

Although community committees and other mechanisms have been developed to encourage civil society involvement in local governance, their effectiveness varies. Regarding accountability, there are few instances where formal mechanisms ensure that state institutions are accountable to the people. In Taiz, for example, while there are formal mechanisms for feedback and meetings, civil servants also focus on ‘balanc[ing] the interests of the political party which has given them a seat, and other stakeholders higher up in the chain’ (Al-iriani 2024: 13).

In Aden, as elsewhere, people express their views through informal means that cannot be described as proper accountability. Accountability, if the word can be used for such an approach, is mostly informal, and therefore has little impact on official actions. It takes place through social media platforms (Basalma 2024), but it is notable that, despite statements to the contrary, freedom of expression is severely limited in Aden, with STC interference and actions. Among recent examples is the suspension of the Journalists’ Syndicate in November 2024, though the IRG ordered its re-opening a few days later (IFJ 2024). In August 2024 in Aden, the STC prevented the holding of an internationally supported youth conference, issuing an order forbidding any meeting not under its own authority (NDI 2024). Several journalists have been attacked and assassinated in recent years, without culprits being brought to justice, and allowing for considerable speculation about the motivation of the attacks’ instigators. There are numerous other examples.

In Aden, official coordination between civil society (mostly humanitarian and charitable non-governmental organizations (NGOs)) and local government is encouraged as long as they are under STC control, with NGOs implementing projects funded by external sources. However, there are cases where ‘local authorities demanding a percentage of implemented projects, licences being required from multiple authorities. … The STC, having the final say on project implementation rather than the governor or the executive office of planning, and the STC favouring its affiliated NGOs while pressuring others that are not affiliated’ (Basalma 2024: 11).

Another example that raises many questions about the legitimacy of state institutions, as well as the role of civil society, is the conflict in Abyan (a governorate to the east of Aden), which has been simmering since mid-2024. Arising from the disappearance of a local leader in June 2024, there have been a series of demonstrations, including blockading of the main road to Aden by truck drivers in October, and demands for answers made to the STC, which is believed to be responsible for the leader’s disappearance.

Conflict resolution: Justice

Throughout Yemen, and for many decades, people have mostly preferred to solve disputes informally through ‘mediation by influential figures and negotiation between the involved parties’ (Al-iriani 2024: 22). These mechanisms include both appeals to tribal customary rules and the use of respected individuals. This is primarily because the formal justice system has been riven with corruption and has the reputation of judging in favour of the highest payer. Thus, whenever possible, people use their community mechanisms to solve problems.

Criteria for deciding which system to use include the nature of the dispute and the social standing of the parties involved: ‘Tribal customs and traditions play a significant role in dispute resolution, particularly in cases involving informal leaders or issues related to land or resources. Mediation and negotiation are often preferred over formal legal processes, as they are more accessible and responsive to local needs’ (Al-iriani 2024: 22). Both systems can be used: if one fails, people move to the other. Although the justice system has always suffered from a lack of trust, mainly due to perceived corruption, this has recently worsened considerably, among other reasons because judges’ training has been reduced in duration, allegedly to fill personnel gaps in the judiciary and to expedite court decisions.

Here again, Taiz is special insofar as its community committees play a significant role in conflict resolution, and are involved in reducing the burden on the police and justice system ‘by promoting the peaceful, non-criminal resolution of communities’ issues’ (Al-iriani 2024: 14). As mentioned above, citizens must pay the police’s expenses for their cases to be addressed in Taiz, and the city’s justice system suffers additionally from being divided between the Ansar Allah and IRG areas, with decisions taken in one jurisdiction affecting the other. In 2020, the IRG ‘issued a decree prohibiting courts under its authority to recognise or enforce rulings issued by courts under the authority of Ansar Allah, not differentiating between criminal (political) and other civil verdicts’

In Hadhramaut, even members of the formal judicial mechanisms consider that community or traditional mechanisms are best approached first, particularly for personal and family issues, but also for conflicts over property. Moreover, in early 2025, the local judicial staff were involved in a long-standing struggle with the authorities over their inadequate remuneration. This led to a strike, and by the end of January, former governor, current PLC Vice President al-Bahsani, mediated between the local authority and judges to end the strike. It was agreed to end the strike on 9 February, but a day later its continuation was announced.

In Aden, the conflict between the IRG and the STC is marked by the suspension of the judicial system by the STC after the clashes of 2019. In 2021, the STC created a new Southern Judges Club ‘to supervise the judiciary and resume the operations of courts and prosecution offices’ to replace the Supreme Judicial Council, which was independent of the STC (Basalma 2024: 10). In 2022, the IRG restructured the Supreme Judicial Council, but the STC-controlled security and judiciary apparatuses did not cooperate: ‘enforcing laws and arresting suspects or criminals often occurs without judicial orders from the prosecution court despite the legal requirement for court orders before making arrests’ (Basalma 2024).

Public services

Both education and health services in Aden, Hadhramaut and Taiz have suffered considerably from the war, with numerous facilities damaged or destroyed. Moreover, some facilities are occupied by military entities, while in all three governorates others have been taken over as housing for IDPs (Al-iriani 2024: 17). Unlike in other parts of the country, the IRG has been paying the salaries of teachers and medical staff in Taiz, both in the area under their control and in Huthi-controlled districts.

Domestic water supply has been a major problem in urban Taiz for at least two decades, and the current supply is in fact better than in many previous eras. In Taiz, the main source of water is in the Ansar Allah-controlled area, giving it the means to put pressure on Taizzis. By contrast, in Aden, the situation has deteriorated due to the exhaustion of the aquifers supplying the city, the ageing and collapsing infrastructure, and the increase in population resulting from the war. Similarly, in Mukalla, the capital of Hadhramaut, the water situation has deteriorated in recent years due to insufficient funding for operation and maintenance, as well as increased demands on the water networks from the arrival of large numbers of IDPs and rural people to the city.

Electricity supply

As elsewhere in Yemen, most people have installed solar panels to provide their basic electricity needs. In addition, Taiz has both private and public suppliers, with different costs attached to each. For example, public electricity costs YER 19 per kWh, while private suppliers charge USD 1 per kWh (at IRG exchange rate YER 2,300+ in March 2025). The latter are mostly under the control of various military leaders. While very little publicly supplied electricity is distributed and bills are not paid, people must pay for privately supplied electricity.

Aden’s electricity supply deserves a book to itself. Despite massive expenditures by various foreign sources, the city continues to experience regular lengthy and unacceptable power cuts. Although the local authority is supposed to manage the power sector, power plants are dependent on fuel, the supply of which is the central government’s responsibility. Delays and major power cuts are due to lack of finance to pay for the fuel and other issues such as political struggles. For example, in February 2025, Aden suffered a complete blackout when the Hadhramis completely prevented any fuel from reaching Aden (Yemen Monitor 2025). As is the case in Hadhramaut, fuel supplies are cut off by tribal and other elements, either to demand more from the government, or simply to disrupt any efforts at normalization of life in both IRG (including STC) controlled areas. Overall, most people do not pay for their electricity.

Shortages of electricity throughout Hadhramaut are mainly due to increased demand and the supply system’s weakness, alongside the increased population. However, the issue also depends on the on–off relationship between the governor, representing the IRG, and the local tribal organizations, with the latter blocking the roads to fuel trucks when in disputes, thus cutting off the electricity supply. In the summer of 2024 in Mukalla, power cuts lasted for 2–12 hours per day.

Formal versus informal rules

The borderline between state administration and what is often described as ‘traditional’ customary mechanisms is thin, and a significant feature of the situation in Yemen. In Taiz and in Hadhramaut, officials ‘understand that they must comply with a mix of formal and informal rules. While the formal rules … are based on the Local Authority Law and the laws that regulate each executive office in the district, the informal rules are based on tribal customs and traditions, political agreements, and personal relationships. … Compliance with informal rulings is … higher in some cases due to strong social pressure and established customs … when a civilian faces confiscation of his land by the military in Ta’izz, legal procedures are not likely to be effective in returning the land to its rightful owner, whereas if tribal mediation is used, the stakeholders are likely to honour outcomes’ (Al-iriani 2024: 13). In Hadhramaut, mediators in conflicts also usually involve sada whose historic role has been to dispense justice and interpret customary rules.

3.3. De facto authority: Ansar Allah centralized rule

Although we only have a detailed study from a Taiz district under Ansar Allah rule, in view of the highly centralized administration implemented by that authority, it is safe to assume that, with a few minor differences, the system applies throughout the area under its control. However, it is worth noting some specificities of the district concerned. Taizziya, also known as Howban, is where the international airport is located. It has one of the country’s major industrial zones and is a transport hub, hence it has been subject to active conflict. Although originally rural, it is now effectively an urban zone. It has also become a stronghold of Ansar Allah rule due to military conquest and its role in mediating an important tribal conflict (Al-iriani 2024: 24).

Elected bodies

As is the case in IRG areas, the elected local council ‘remains inactive, but some members still function under the elected specialised committees … the district is nominally managed by the district director and the executive offices, with an appointed supervisor … embedded within each local authority institution to ensure adherence to directives from the central authority of Ansar Allah’ (Al-iriani 2024: 27). Supervisors are Ansar Allah loyalists who have been appointed at all levels of government by the leadership. Their role is to ensure that officials, many of whom hail from an earlier administrative period and are not supporters of the movement, do indeed implement Ansar Allah policies. They are also there to ensure that the maximum amount of funds is directed to the movement. Supervisors are widely despised and accused of being ignorant and unqualified, and lacking the information and understanding required to manage the institutions concerned.

As the report for Taizziya points out, and as is the case elsewhere, ‘decision making regarding director-level appointments and other key matters is centralised, with the governor of Taiz and his Ansar Allah supervisors overseeing these decisions’ (Al-iriani 2024: 27).

Financial management and revenue collection

In this area, fees are collected locally, while taxes and zakat are centralized. The industrial zone with factories owned by the most important Yemeni companies, including the Hail Saeed Anam conglomerate, have attracted close attention from Ansar Allah leadership, including frequent visits by the president of the Ansar Allah government. In 2017, the area was estimated to generate USD 50-60 million of tax revenue (Sana’a Center 2017), an important sum for the authority. Extortion is a mechanism used by Ansar Allah to increase its revenues: in Taiz, it has used a regulatory body to demand very high fees: ‘ AA [Ansar Allah] officials forcibly enter these facilities, conduct inspections, and then demand substantial sums of money. Noncompliance is met with threats of closure, effectively extorting funds from factory owners.

Here, as elsewhere, Ansar Allah has imposed a new 20 per cent zakat tax (known as khums) on a range of activities to directly benefit members of the sada social group. It also collects special taxes and fees for decorations and other celebratory activities on its selected national anniversaries, whether religious (such as the Prophet’s birthday) or secular (such as the anniversary of their takeover of Sana’a).

Civil society, accountability and community participation

Although civil society is strictly controlled under Ansar Allah rule, there have been cases where ‘the community has been able to influence decisions made by the local authorities, such as the removal of some governors and security directors in Taiz over the past nine years’ (Al-iriani 2024: 28). Political parties are not allowed to operate, except for the GPC, which is part of the Ansar Allah government in Sana’a. Nevertheless, party leaders have often been replaced by supporters of the Huthi movement. Surprisingly, but clearly due to their local influence, both the Islah party and women activists are allowed to operate in Taiz though in some cases their leaders have been replaced by Ansar Allah supporters. Here, as elsewhere, community organizations have been involved in ‘mediating conflicts, providing essential services and advocating for community needs’ (Al-iriani 2024: 28).

Conflict resolution and justice

The Ansar Allah head of police in Taizziya ‘has been accused of multiple crimes, including the storming of a courtroom … he also murdered … there are unofficial payments made directly to the officers, particularly concerning qat, which end up in the officers’ personal accounts’ (Al-iriani 2024: 35), but has not been removed. In contrast, the presence of police officers, including women, in malls and other public places has enhanced a feeling of security. When needed, police action is complemented by that of military units from Ansar Allah-related forces.

The involvement of unqualified ‘supervisors’ has distorted the justice system, as they solve ‘issues according to the group’s customs, rules and regulations, introducing discrepancies and biases’ (Al-iriani 2024: 36). In other words, they prioritize the policies and strategies of the Huthi movement over just legal procedures.

Public services

As is the case elsewhere, public services suffer from all manner of problems, ranging from destruction of infrastructure to delayed payment of salaries. The education system suffers from low quality, ideological changes made to the syllabi, and imposition of ‘summer camps’ whose role is to give children military training and to indoctrinate them with Ansar Allah ideology. Teachers and medical staff have been paid their salaries mostly by the IRG, not by the Ansar Allah authorities. This differs from the situation in other parts of Huthi-controlled areas, where teachers are rarely paid.

With respect to medical services, one problem in this area is the fact that major medical facilities are located in the IRG-controlled part of the governorate, so people must cross the ‘border’ to access hospital services, which is a serious problem in times of active military conflict.

Water supply is a major problem. One of the main aquifers supplying all of Taiz, that of Hayma (located in Taizziya), was first developed (meaning its water was extracted) in the late 1980s. The water was transferred to Taiz city, depriving the area of both agricultural and domestic water, thus destroying its rural economy without any form of compensation. Once this supply was exhausted, the neighbouring district Habir (located in Ibb Governorate) was intended to replace it, but popular resistance prevented drilling of the wells. Water in the district now comes from local wells using water polluted by sewage and other waste, and providing an insufficient supply. In the neighbouring governorate of Ibb, conflicts over solar water projects have taken place between communities and groups linked to the Huthis.

Electricity, alongside domestic solar power, is also shared between public and private suppliers. The head of the public supplier is also head of a private provider. Beyond this, private electricity companies pay the Public Electricity Corporation ‘rent’ for each generator they use (about YER 500,000 per month) and therefore increase the private supply at the expense of public electricity, while overcharging users. This is the case regardless of the decision by the Ansar Allah government to regulate electricity generation.

Formal and informal justice mechanisms

As is the case elsewhere and, indeed, challenging widespread beliefs about Ansar Allah rule, the role of tribes and other ‘customary’ or non-state institutions remains important. ‘While official laws and AA regulations are formally recognised, local tribal customs and traditions significantly influence day-to-day governance, and the implementation of these laws often overshadows formal regulations. … An incident involving gunfire … prompted immediate investigative action and the individual responsible … was swiftly apprehended. Conversely, some of the gunfire incidents are overlooked when AA or prominent figures associated with AA are the ones responsible’ (Al-iriani 2024: 34).

Issues of justice are those most frequently mentioned with respect to informal practices. People ‘often rely on their deeply ingrained customs and traditions to resolve disputes, frequently taking precedence over formal legal mechanisms. Disagreements between neighbours or community members are commonly settled through the mediation of a respected elder or a neutral third party, leading to quick and effective resolutions. However, the approach to conflict resolution is varied, involving a mix of legal, customary and sometimes informal interventions, such as tribal sheikh mediation in service disruptions, road accidents or accidental killings. Indeed people still prefer informal mediation because the justice system is too slow’ (Al-iriani 2024: 36).