The Journey of a Ballot Paper

A Practitioner’s Guide

Executive summary

This Technical Paper provides a comprehensive overview of key considerations when designing ballot papers, focusing on accessibility, security, simplicity, cost-efficiency and legal compliance. The paper covers pre-election phases, including setting timelines; designing, procuring and distributing ballots; and ensuring accessibility and voter clarity. It highlights environmental and cost considerations and balanced budgeting.

The section covering the election phase includes considerations for facilitating ballot secrecy, accurate ballot marking and transparency in vote counting, as well as training polling staff, especially on how to secure ballot papers. The section on the post-election phase stresses the proper storage and potential reuse of ballots for auditing or dispute resolution, along with environmentally sound disposal. The paper also includes insights on recent challenges, such as Covid-19’s impact on election processes, and recommends adaptations like postal voting, while explaining how to uphold ballot secrecy and ensure voter support.

The purpose of this resource is to help election practitioners achieve a transparent, secure and cost-effective election process.

Introduction

Ballot papers are fascinating. They are the centrepiece of any election because they provide a physical record of how people voted. They offer a choice to voters and represent a powerful democratic symbol. They are a target for political parties and candidates who want to be on the ballot and a magnet for perpetrators of electoral malfeasance who seek to distort election results. They are also a logistical challenge for many electoral management bodies (EMBs) around the world, which are tasked with ensuring the security and integrity of elections.

The paper ballot has a rich history. Its origin can be traced to ancient Rome, but other methods have also been used to record votes throughout history—for example, palm leaves in ancient India, pieces of pottery in ancient Greece and, until recently, glass marbles in The Gambia. The paper ballot may also become history, as many countries are considering, or have already introduced, various forms of electronic voting (Wolf, Nackerdien and Tuccinardi 2011; Van der Staak and Wolf 2019). For now, the paper ballot remains the most commonly encountered form of voting.

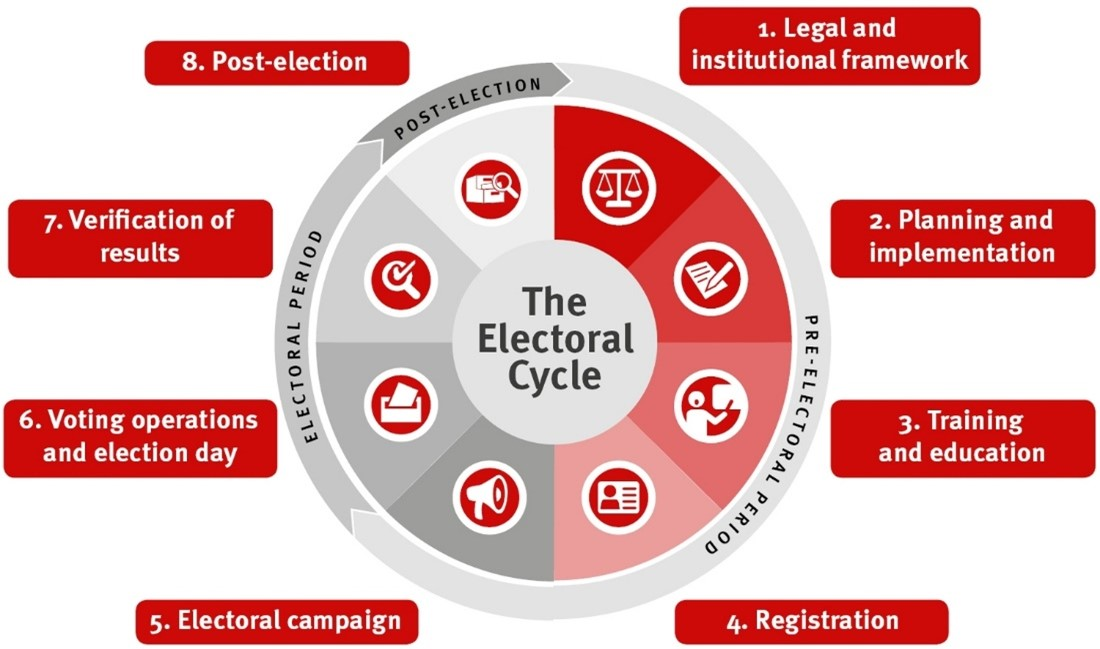

This guide tracks the ballot paper’s journey throughout the electoral cycle—from the pre-election period to election day and the post-election phase of the electoral process (see Figure 1)—gathering in one place many considerations pertaining to ballot papers, while sharing examples of good practice and drawing attention to useful resources. Reflecting recent developments, the guide considers elements of the electoral process affected by the Covid-19 pandemic and offers considerations for the future. Although election practitioners are the primary audience, the guide will also be useful to anyone interested in elections.

1. Cross-cutting considerations

A number of considerations apply to each stage of the ballot paper’s journey. Three of these—environmental considerations, costs and the quality of the legal framework—are highlighted below:

- Environmental considerations. Elections leave a carbon footprint, which includes emissions from the production, distribution, collection, storage and eventual destruction of ballot papers.

- Costs. EMBs strive to deliver the best process within a limited budget. This necessitates an examination of various options, ensuring cost-effectiveness and gaining the confidence of stakeholders, among other factors, to make smart choices that avoid waste and do not compromise the overall quality of the electoral process.

- Quality of the legal framework. The quality of the rules and regulations affects each stage of the electoral process. Stable, clear and consistent statutes and implementing regulations enable all electoral stakeholders to plan their actions and fulfil their duties with predictability and certainty.

2. Pre-election period

2.1. Timetable

The dates of elections and referendums are determined by law. Constitutions typically provide the term of office of the highest elected bodies, such as parliaments and presidents, and mandate that elections be held at the end of these terms. The exact dates are then set by authorized officials, enabling EMBs to create a timetable for the electoral process. This timetable should include statutory deadlines—for example, for receiving nominations from prospective candidates or for the start of the regulated campaign period. EMBs often publish these timetables to inform voters and other election stakeholders and enable them to plan their actions (see Table 1).

| Thursday 19 January | Prime Minister announces date for 2023 general election. |

| Friday 14 July | Regulated period for election advertising expenses begins Beginning of 3-month period when voters of Māori descent who are already enrolled cannot change between the general and Māori rolls. |

| Friday 8 September | Dissolution of Parliament. Last day for registration of parties and logos. |

| Sunday 10 September | Writ Day—the Governor General issues formal direction to the Electoral Commission to hold the election. Voters enrolling after this date cast a special vote. |

| Noon, Friday 15 September | Nominations close for candidates. |

| Saturday 16 September | Names of electorate and list candidates released on vote.nz. |

| Wednesday 27 September | Overseas voting starts. Telephone dictation voting opens. |

| Monday 2 October | Advance voting starts. |

| Friday 13 October | Advance voting ends. |

| Friday 13 October | Regulated period ends. All election advertising must end. Signs must be taken down by midnight. |

| Saturday 14 October | Election day. Voting places open from 09:00 to 19:00. Election night. Preliminary election results released progressively from 19:00 on <www.electionresults.govt.nz>. |

| Friday 3 November | Official results for the 2023 general election declared. |

| Thursday 9 November | Last day for the return of the writ. |

EMBs use an election timetable to plan their activities, including setting internal deadlines for the completion of key tasks and designating responsible staff. Internal EMB calendars and similar planning tools may be shared with election observers and party agents to demonstrate transparency and accountability in the EMB’s work.

An EMB’s planning calendar should be realistic and based on prior experience with accomplishing similar tasks. If the amount of resources available for particular tasks differs from prior electoral cycles, the deadlines should be adjusted accordingly. The calendar must also be consistent with the statutory deadlines for the election. For example, an EMB cannot start printing ballots before the deadline for the registration of electoral contestants. On the other hand, the ballots’ paper specifications and security features can be decided early on in the process. If statutory deadlines are known to present serious technical or logistical challenges, the EMB should use its authority to seek legislative change well in advance of the election or obtain more resources to meet these challenges. Contingency plans should also be made for any potential worst-case scenarios—for example, if a tender for procurement of supplies fails or if additional contestants are added to the ballot following court appeals after the ballots are printed.

An EMB’s operational plan with respect to ballot papers will depend on the scope of its responsibilities. In many countries EMBs are in charge of printing ballots and delivering them to polling locations, which requires timely arrangements to procure ballot paper as well as printing and transportation services. Less commonly, ballot papers are printed by political parties, with EMBs providing only the design and paper specifications. This approach is practised, for example, in Greece, where some of the responsibility for timely arrangements also rests with political parties.

2.2. Procurement

Procurement of election supplies, including ballot papers, may be subject to general rules for public procurement. These rules may require that the EMB hold tenders, review offers and award contracts to the winning suppliers. It is important that the EMB employ experts on public procurement to ensure compliance with the rules and the requisite transparency of tendering procedures. On the other hand, exigencies of the electoral process may require that procurement of at least some election supplies be exempt from the general rules of public procurement. If this is the case, such exemptions should be clearly regulated, and the EMB must ensure that these exemptions are not abused.

Experience from prior electoral cycles is a valuable guide on potential pitfalls in the procurement process. Since electoral supplies must be produced in large quantities and in line with particular specifications, there may be few vendors in the country capable of meeting the requirements. Even where local suppliers are available, other considerations—such as suspicions on the part of electoral stakeholders—may lead the EMB to choose suppliers from abroad. Obtaining materials from abroad may increase their cost, requiring the EMB to revise its budget or request additional resources. Such challenges could complicate even a well-planned procurement process, as the example from the Philippines (see Box 1) demonstrates.

Box 1. Bidding process to supply election materials in the Philippines

The Commission on Elections (Comelec) published an invitation for suppliers of ballot paper and marking pens to submit bids in August 2018 for elections to be held in May 2019. Only one company submitted a bid and advanced to the next stage, where the bid was examined for eligibility and to determine whether it met the technical and financial requirements. At this stage the company’s sample pens were found not to comply with the required technical specifications, and its bid was disqualified.

An invitation to bid for a second tender was published in September 2018. Three companies attended a pre-bid conference, but none of them later submitted a bid, leading Comelec to approve a negotiated procurement and increase the contract amount by 10 per cent.

A third bid notice was published in October 2018, three months after the first bid and two months before the ballot paper would be needed in December. In this round additional requirements were added for the ballot paper, and the specifications for the marking pens were changed with respect to the tip shape, which was the subject of contention in the first bid. Only one company responded to the third call—the same company which participated in the first bid—and entered procurement negotiations. The contract was eventually awarded to this company, with an even higher price tag than its initial bid. Owing to the late procurement of the ballot paper, the printing of the ballots was delayed by one week. Voters also complained about the quality of the pens supplied.

2.3. Design

The EMB is typically responsible for designing the ballot papers, even where it is not responsible for printing the ballots. The ballot design should make it easy for voters to participate in an election or referendum. The choice presented to voters on a ballot depends on the type of election and the electoral system. In elections for executive offices, such as presidents, governors or mayors, voters typically have the choice of individual candidates nominated by political parties or independently. In elections for legislative offices, such as parliaments, assemblies or councils, voters are usually presented with a choice of lists or individual candidates, and may be asked to rank them in their order of preference (Reynolds, Reilly and Ellis 2005). In referendums voters are asked to answer one or more questions.

The law may set general or specific requirements for the ballot design. The EMB is typically mandated to determine the ballot form, and it has discretion to decide on issues which are not addressed in the law. In Botswana (1968), for example, article 48 of the Electoral Act provides for ‘a ballot paper in a form to be determined by the Commission and having a serial number printed on it’. By contrast, article 30 of the Election Law of Kyrgyzstan (2011) also mandates the EMB to determine the form of the ballot, while specifying that:

Ballots for a presidential election shall contain the [full] name and date of birth of the candidates in the order determined by lot. … To the right of the [contestant data] shall be an empty square. At the end of the list of candidates … shall be a line ‘Against all’, with an empty square to the right of it. … Each ballot shall contain an explanation of how it should be completed, information about the producer of the ballot and the print run. Ballots shall be printed on paper with such thickness that a voter’s mark cannot be seen on the reverse side of the ballot.

Good practices in ballot design can be summed up by the ACCESS rule, where A stands for accessibility; C, for clarity; C, for costs; E, for equality; S, for simplicity; and S, for security.

These considerations are discussed in more detail in the sections that follow.

2.3.1. Accessibility

Accessibility broadly refers to the enfranchisement of all eligible voters. Naturally, the measures required for effective accessibility go well beyond ballot design as such and encompass voter information, education, accessible campaigning and media coverage, access to polling stations, alternative voting procedures and other areas. Accessibility of the ballot design should be considered in this broader context.

Ballots should use sufficiently large fonts to ensure that they are easy to read. Photos and symbols may be used to make the ballot more accessible for illiterate voters and voters with learning disabilities. Generally, ballots which require voters to write in contestants fall short of accessibility standards. For example, observers at the 2004 Philippines elections noted that voters were required to write the names of 30 candidates. In response, observers recommended that fully printed ballots be used in future elections so that voters could mark their choices. This suggestion does not preclude the possibility of giving voters an opportunity to write the name of a candidate on their ballot, as practised, for example, in some states in the United States.

For voters with communication disabilities, access to the ballot may require the use of auxiliary aids and services. For people with impaired vision, for example, such services may include the provision of a qualified reader, information in large print or Braille, accessible electronic information or an audio recording of printed information. Auxiliary aids and services for people who are deaf or have a hearing loss may include sign language interpreters, captioning and written notes (United States Department of Justice 2020).

2.3.2. Clarity and simplicity

Ballots should be designed to offer voters clear choices and avoid confusion in order to minimize errors which may render votes invalid.

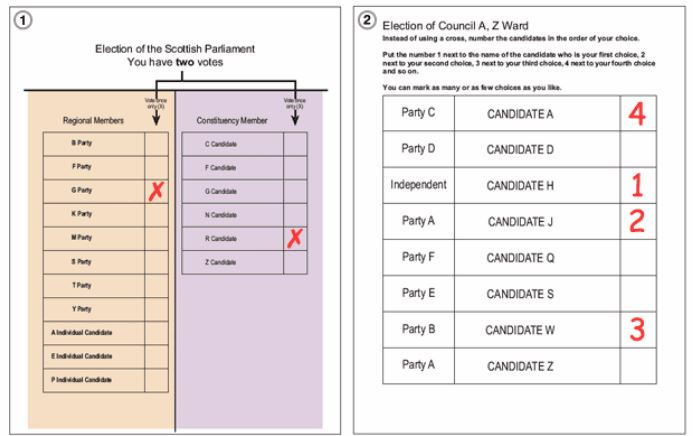

The illustration in Figure 2 shows an incorrectly completed ballot from the 2007 parliamentary elections in Scotland. The ballot contained the following instruction: ‘You have two votes’, with arrows leading to two columns (for regional and constituency members). Some voters understood this instruction to mean that they could place two marks anywhere on the ballot paper rather than making one mark on each side of the ballot paper.

Citizen observers at the 2017 parliamentary elections in Kosovo reported an example of an insufficiently clear ballot design. According to these observers, voters confused candidates’ numbers with the numbers of political entities listed on the left side of the ballot, resulting in an increase in the number of invalid votes (Democracy in Action 2017).

Practical advice on designing clear and user-friendly ballots developed by the Center for Civic Design in the USA includes using lower case letters, avoiding centred type, and using sans serif typefaces, sufficiently large font sizes, and clear and simple language (Center for Civic Design 2018a). The Center for Civic Design also recommends placing instructions for voters where voters will need them, including information that will prevent voters from making errors, writing in short sentences using simple everyday words, writing in the active voice, numbering steps if the instructions include several steps, and keeping paragraphs short and separating them with a space (Center for Civic Design 2018b).

International observers at the 2003 elections in Nigeria reported that voters expressed their choice by placing their thumbprint on the ballot next to their preferred party, in a space that was far too small for the average thumbprint. The ballot was then folded, making it likely that the thumbprint would smudge other parts of the ballot, casting doubt on the voter’s intention. Ballots were indistinguishable except for the name of the election printed at the top. The ballot paper displayed symbols for all 30 registered political parties even in areas where only a fraction of those parties were fielding candidates (International Republican Institute 2003: 14).

The issues described above and similar shortcomings in ballot design could be detected through a usability exercise of sample ballot papers. New ballot paper design testing does not need to be arranged on a large scale: practitioners recommend a group of 12–15 voters per canvasser. Usability testing can be carried out anywhere voters are likely to be found—in a library, a marketplace or simply on the street. Voters should not be assisted while filling out their ballot, but the interviewer should ask them about their experience after the test and also pay attention to any comments or hesitations voters express. The ballot design could be tested at various stages of its development—from the first prototype to the final layout. It is recommended, however, to test one version at a time (Center for Civic Design 2018c).

2.3.3. Costs

While recognizing that Afghanistan’s 2005 parliamentary and provincial council elections were hardly typical, the fact that more than half of the ballots printed for those elections were not used (see Box 2) serves as an example that highlights the importance of cost analysis in elections more generally.

Box 2. Afghanistan 2005

In 2005 a total of 40 million ballot papers were printed for parliamentary and provincial council elections—20 million for each election. The EMB Secretariat reasoned that the 40 million ballot papers were necessary to account for all eventualities, given that voters were not allocated to polling stations and based on the presumption that a huge number of ballots would be needed as a strategic reserve.

At the end of the electoral process, however, the majority of the ballot papers—approximately 27 million—were left unused. The printing and transportation costs were considerable, owing to the size and weight of the ballot papers and several other items related to the electoral process, and a number of additional procurement arrangements (e.g. larger ballot boxes) were necessary.

Given all these logistical challenges, the elections incurred a direct cost amounting to USD 159 million, or an average of USD 24.8 per voter. This is a high price by any standards, even in a post-conflict environment like Afghanistan.

Cost considerations very much depend on the context: some countries can and do spend more on elections than others. However, EMBs usually operate with a limited budget and strive to obtain the best value for money. Every choice made with respect to ballots—such as paper quality, ballot design and security features—has financial implications. These implications should be properly assessed and budgeted for.

In countries where separate ballots are printed for each party, ballot production results in considerable waste. For example, some 673 million ballot papers were printed for different races in the 2018 general elections in Sweden, with 7.5 million registered voters. This kind of wastage raises both financial and environmental concerns (OSCE/ODIHR 2018: 4). Such systems may also create an additional barrier for political newcomers who do not benefit from public subsidies. In Greece, where the costs of printing and delivering ballots are shouldered by the parties, smaller parties face a greater challenge (OSCE/ODIHR 2019a: 7).

2.3.4. Equality

Equal treatment of election contestants before the law and by the authorities is one of the fundamental principles of a democratic electoral process. This principle also has practical implications for ballot design, in particular with respect to the order of contestants on the ballot and the way they are presented.

The order of contestants on the ballot is not entirely inconsequential. Research has shown that the first place on the ballot gives a certain electoral advantage. To preserve equality of opportunity among the election contestants, their order on the ballot is commonly determined by drawing lots. Removing the first-position advantage could be achieved by randomly ordering the ballot positions across ballot papers so that each candidate appears at each ballot position an equal number of times. While some researchers have argued for such a system (Reidy and Buckley 2015), its implementation would deprive election contestants of the possibility to campaign with their number on the ballot, which is a common practice in many elections.

The second aspect of equality is the presentation of contestants on the ballot. Ballot presentation may give voters cues about a certain party or candidate, intentionally or inadvertently. No advantage should be given to any candidates or parties through their presentation on the ballot—for example, by using a different typeface or font size. In addition, special care should be taken where ballots feature candidate photos, party logos or symbols, or other information to ensure that this information is presented equally. Where EMBs themselves choose symbols for election contestants in order to make ballots more accessible for less literate voters, such symbols should be equally neutral.

2.3.5. Security

Ballot papers often include security features, especially where electoral stakeholders have concerns about potential fraud at the ballot box. Some possible security features include the use of a background design, microprinting, watermarked paper, ultraviolet prints, heat-sensitive ink, holographic images, anti-photocopy marks, serial numbers and bar codes. Security features come at a cost, so their potential benefits should be weighed against their costs, and various alternatives should be considered.

The introduction of security features should prevent electoral fraud and reassure the public that effective measures are being taken to preserve electoral integrity. Voters should be informed about any measures that will directly affect them at polling stations, such as the use of indelible ink. Other security features could be publicized to increase public confidence in the electoral process. At the same time, there are good reasons to avoid disclosing some security elements so that their protective function is not lost.

Some countries put serial numbers on ballots as a safeguard against electoral fraud. The use of serial numbers makes it possible to track ballots to specific polling locations. They may also be used to link ballots to individual voters. In the United Kingdom the number of the ballot paper issued to a particular voter is recorded against that voter’s number on the voter list. A court may subsequently order that ballot papers be traced to voters to investigate allegations of fraud. Although the public and other stakeholders generally have faith in this system, it poses considerable risk to the secrecy of the ballot. Indeed, ballot secrecy considerations have led other countries to abandon serial numbers on ballots, as Malaysia did in 2006. Other countries, such as Canada, use serial numbers on a detachable counterfoil and stub but not on the ballot paper itself (ACE Electoral Knowledge Network 2010).

Preventing electoral fraud is unquestionably an important aim, especially in countries with a history of challenges to electoral integrity and a low level of trust in elections. There are, however, alternative ways to pursue this aim through enhanced ballot security, as discussed above, without jeopardizing ballot secrecy. It should be recalled that ballot secrecy is regarded as one of the cornerstones of contemporary democratic elections, reiterated in universal and regional international instruments. Guided by this understanding, the Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly (2007: paragraph 12.1.6) called on member states to guarantee secret voting for all citizens and, to this end, to ‘abolish the use of ballot papers attached to counterfoils and bearing serial numbers’.

2.4. Postal ballots

The Covid-19 pandemic renewed interested in postal voting, both in countries with extensive experience with this voting method and in those without such experience. A number of factors should be considered to ensure informed decision making with respect to postal ballots, including the reliability of the postal service and the voter registration system, as well as the trade-offs with respect to secrecy, freedom of choice and accessibility of the ballot.

The reliability of the postal service is an obvious first consideration with regard to postal voting. The EMB should make its own assessment based on available information, including user experiences and public perception. In addition to its proper functioning, the postal service should also provide adequate guarantees of security against intentional interference (Venice Commission 2002: paragraph 38).

Postal voting presents opportunities to exploit weaknesses in voter registration systems for fraudulent purposes. Such weaknesses have been painfully exposed—for example, in the UK. In the 2004 local elections in Birmingham, candidates and party agents were able to obtain and alter completed postal ballots, and they also obtained a large number of blank ballot papers which they used to impersonate legitimate voters. These manipulations were enabled by the lack of safeguards in the voter registration system, which required only a person’s name and address for registration, without any personal identifiers. The returning officers who processed applications for registration had no obligation to check the validity of the information submitted and few resources to do so. Voters were legally allowed to register in different localities so long as they maintained residence there. These and other weaknesses made postal voting fraud ‘childishly simple’, in the words of international rapporteurs (Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe n.d.). Those making decisions on postal voting should consider how voter registration systems may be improved (United States Election Assistance Commission n.d.). For any existing loopholes in voter registration, additional safeguards should be considered to prevent fraud.

The purpose of ballot secrecy is to protect voters’ freedom of choice. Postal voting takes place in an unsupervised environment, which removes the protections of ballot secrecy available at polling stations. The EMB should be aware of this trade-off in its decision making. Additional measures could be considered to mitigate some risks, even though they may not be eliminated completely. In Australia, for example, postal ballots must be completed in the presence of a witness.

Voting in an unsupervised environment also means that the voter does not have the usual support of polling staff. This affects ballot accessibility for voters who are unable to read or understand voting instructions. Voters who accidentally spoil their ballots may not be able to get another one due to a lack of time or logistical capacities. These are the reasons why a higher percentage of postal ballots are typically invalid compared voting in person. In the 2016 presidential election in Austria, for example, 5.25 per cent of postal votes were invalid, primarily because voters had not provided a signature confirming that they had cast their vote ‘personally and in secret’ (OSCE/ODIHR 2017: 8).

The above considerations on ballot paper design are equally applicable to postal ballots. In addition, the content and design of the materials and instructions are of particular importance in postal voting. Useful tips for designing postal voting materials include using different colours for different voting materials, writing clear instructions and placing them where voters will need them, using checklists, explaining how to return the ballot and reminding voters of the deadlines (Center for Civic Design 2018d).

2.5. Referendum questions

The same considerations on ballot design generally apply to referendum ballots, although the latter tend to be simpler if only a small number of questions are put to a vote. In addition, it is recommended that questions put to a referendum preserve unity of form, unity of content and unity of hierarchical level (Venice Commission 2022).

Unity of form means that the same question should not combine a specifically worded proposal or amendment with a generally worded one or a question of principle—for example, asking voters if they are in favour of membership in a particular international organization. Unity of content means that voters should not be asked to give one answer to several questions which are not intrinsically linked, since a voter may be in favour of one proposal but against another. Unity of hierarchical level means that the same question should not simultaneously apply to legislation of different hierarchical levels—for example, a constitution and an ordinary statute.

2.6. Voter information

The term ‘voter information’ typically encompasses basic knowledge about the electoral process necessary to exercise the right to vote. This term is narrower than ‘voter education’, which also includes knowledge about the significance of electoral processes and democratic participation. A still broader term, ‘civic education’, denotes the knowledge and skills of an active citizen in a democracy more generally, including between elections (ACE Electoral Knowledge Network n.d.).

Voters should receive all information necessary for exercising their rights, including any important electoral deadlines, such as the deadline to register or request a postal ballot. To this end, voter information campaigns normally cover election dates; the opening and closing times of polling stations; voting methods (such as voting in person, through a proxy or by post) and how to use them; polling locations and how to find them; and election day procedures (such as voter identification at polling stations and the rules for marking ballots). In environments where voter information is especially important, voters should also be reassured about the measures taken to maintain the secrecy and security of the ballot.

Voter information is normally the responsibility of the EMB. A well-planned voter information campaign provides timely messages through a variety of media, including social media, whose role has grown considerably in this process (Kaiser 2014). Voter information should target different groups, including the socially disadvantaged. For people with disabilities, appropriate means of communication should be identified, and voter education should be carried out with the participation of organizations for people with disabilities.

The intensity of voter information campaigns depends on voters’ familiarity with polling procedures. Where polling procedures have been the same for several electoral cycles, voters will need only to be reminded of them, with more attention given to first-time voters. On the other hand, voter information should emphasize any changes from previous elections, including in the electoral system, polling locations, voter registration or identification requirements, voting days and times, and the rules for marking the ballot. Major changes which require voters’ participation should be communicated in a timely manner and be accompanied by other measures necessary for their implementation. For example, the authorities in Kyrgyzstan introduced biometric voter registration, which was made mandatory for exercising the right to vote, in April 2015, prior to parliamentary elections scheduled for later that year, in October. International observers noted that some citizens were effectively excluded from biometric registration because they were homebound or lived in remote locations or abroad. Observers recommended further measures to be undertaken to register all eligible voters (OSCE/ODIHR 2016: 9–10).

2.7. Training of polling staff

Knowledgeable polling staff are key to the success of any election. All levels of the election administration should know their duties and tasks with respect to ballot papers. Although the EMB often handles the printing and distribution of ballots centrally, regional or local authorities or political parties may be responsible for these tasks instead. Polling staff in every system should have knowledge of the procedures for handling ballots prior to voting, on election day and thereafter.

The Covid-19 pandemic brought a new dimension to polling staff training related to health precautions. Elections organized during the pandemic had to include training for polling staff on the protective measures designed to counter the spread of the virus. The content of these measures were meant to be determined based on the guidance of public health authorities and depended on available resources. The effectiveness of these measures largely depended on the ability of polling staff to enforce them, including by organizing procedures at polling stations and counting locations with respect to social distancing. This called for timely guidance and training, well ahead of planned elections (United States Election Assistance Commission 2020).

Models for polling staff training differ widely, depending on how the election administration is structured and recruited. Good practices for staff training include interactive, hands-on exercises which enable polling officials not only to receive the information they need but also to apply it in practice and develop the relevant skills. The Covid-19 pandemic spurred interest in remote training methods for polling staff across the globe. The technical capacity of EMBs to develop and offer such training will differ, but the challenge of preserving the practical dimension and ensuring skills development will remain relevant for all training efforts.

Ensuring the secrecy of the ballot should be an integral part of staff training. Electoral laws and regulations provide specific measures to protect ballot secrecy, such as making sure that voters mark their ballots only in the privacy of booths or behind voting screens, making sure that polling officials instruct voters on how to properly fold their ballots or place them in envelopes before depositing them into the ballot box, prohibiting group or family members voting together, banning photographing ballots and other measures. Voter information campaigns can increase voters’ awareness of these safeguards and help them understand their importance, but ultimately the enforcement of these measures is in the hands of polling staff.

The rules for marking ballots may be rather strict in some countries, which places additional importance on the rules for determining ballot validity. Training for polling and counting staff should emphasize consistency in determining valid votes to prevent any partisan bias in the process. Since differences of opinion on the matter of ballot validity may easily spark friction between polling staff, training should cover procedures and skills for resolving such differences.

2.8. Printing and distribution

Electoral calendars should allow sufficient time for ballot production and distribution to polling locations. Where EMBs are in charge of printing ballots, they should also require that printing companies maintain appropriate controls to ensure the security and integrity of ballots. EMB personnel are often present on-site while ballots are printed. The ballot printing process may be of interest to election observers and the media, in which case arrangements should be made to grant them access to the production facility. The EMB should use this opportunity to showcase the transparency of their work and educate the public about the measures taken to ensure the integrity of the process.

Plans should also be made for the storage and distribution of printed ballots, which must subsequently be transported to polling locations. The schedule for ballot distribution should be aligned with other election materials that are being procured and distributed to polling sites. The EMB should make plans for security during transit and at polling sites and communicate these plans to the election administration, any institutions involved in the transportation and security personnel. Ballot distribution and contingency plans must ensure that sufficient numbers of ballots are available at all polling locations.

Box 3. Poland 2007

Anticipating a low turnout for the pre-term parliamentary elections in Poland on 21 October 2007, and following previous practice, constituency election commissions (CECs) arranged to print ballots for only 80 per cent, on average, of the number of eligible voters in their constituencies. CECs kept a certain number of ballots in reserve, issuing less than 80 per cent to the precinct election commissions (PECs). However, turnout in some constituencies, especially in large cities, exceeded the election administration’s expectations. In some instances, the PECs did not request additional ballots in time, and in others the logistical support staff from the municipalities and the National Electoral Commission failed to deliver the requested additional ballots in time. As a result, voting was interrupted at approximately 50 polling stations, and voting hours had to be extended beyond 20:00, when polls were supposed to close.

Ensuring the security of ballots before the beginning of voting is essential in environments where the integrity of elections is questioned. Procedures for the handover of delivered ballots and their storage until the commencement of voting need to be detailed and should include verification and recording of the numbers of blank ballots and other materials. Additional transparency measures may be undertaken by allowing partisan and non-partisan observers to be present for the delivery of ballots and other election materials and again at the opening of the polls, giving them an opportunity to verify that ballots have not been tampered with.

3. Election day

The term ‘election day’ reflects the practice whereby voting is held on a single day, which is the case in many countries. However, some countries allow voters to cast their ballot early, for the sake of convenience. In Norway, for example, early voting begins one month before election day, and voters can vote even earlier by depositing their ballot in their municipality. Elections may also be administered in phases for logistical reasons, as is done in India, where the 2014 parliamentary elections were held in nine phases from 7 April to 12 May. The practice of one election day may be changing due to the Covid-19 pandemic and the resulting need to avoid large gatherings of people in one place at one time. Holding elections over more than one day may well become the new normal, at least in some countries.

Extended voting times present additional challenges for maintaining the security of the ballots and other election materials over longer periods of time, especially in environments where electoral malfeasance may be suspected. Stakeholders should be reassured that all sensitive electoral materials, including ballots, were kept secure and were not tampered with throughout the voting period and during the counting and tallying of votes.

If multiple voting methods are used, such as postal voting and early voting, it is important that the EMB develop procedures for each method and that the polling staff understand them. Where multiple elections take place at the same time, managing several races—potentially under different electoral systems, with a variety of voting methods and over extended periods of time—adds a level of complexity that calls for a high degree of professionalism from polling staff. Decision makers who are contemplating the introduction of such complexities should consider what additional investments or changes should be made for the recruitment and training of polling staff to ensure the requisite professionalism on their part.

As a safeguard against multiple voting, voters’ fingers are marked with indelible or ultraviolet ink in some countries. This step should take place after the voter is identified and receives their ballot, to prevent marking voters who may not be entitled to vote at a particular polling station.

3.1. Ballot secrecy

While many societies have employed open voting at periods in their history, contemporary democratic elections take place by secret ballot (UNGA 1948: article 21; 1966: article 25). Ballot secrecy ensures that voters may express their choice freely, safe in the knowledge that it will not be revealed and they will not suffer any retribution for supporting one candidate or party over another. Voting procedures should be, and normally are, designed to preserve ballot secrecy. However, inadequate implementation may jeopardize ballot secrecy.

The design of the ballot paper should be such that the voter’s choice is not revealed when the ballot is deposited in a transparent ballot box. To this end, it may be preferable to use semi-transparent (translucent) ballot boxes, which make it difficult to see the marks on ballots. Similarly, the quality of ballot paper and pens provided for marking ballots should be such that the mark would not be visible on the other side of the paper.

Polling stations must include spaces where voters can mark their ballots in secret, such as booths or areas separated by voting screens. Screens and booths should be set up in a way that prevents others from seeing how ballots are marked. Polling staff should prevent voters who attempt to accompany others (practices known as ‘group voting’ or ‘family voting’) unless they are assisting disabled voters at the latter’s request.

In countries where voters pick the ballot of their chosen contestant, concerns have been expressed over ballot secrecy where voters openly pick the ballot of their choice (Elklit 2018). Secrecy is better protected if voters receive the ballots of all contestants from the polling officer and then are asked to put the ballot of their choice into the envelope inside the polling booth, as is the case in Greece. The remaining ballots are put into a bag outside the booth.

Where small groups of voters cast ballots together—for example, in remote areas or in institutions served by a mobile ballot box—these votes should not be revealed or counted separately. During the 2019 presidential election in North Macedonia, for example, international observers expressed concerns that votes from polling stations with fewer than 10 voters as well as from penitentiary institutions and special polling stations for internally displaced people were counted and recorded separately, which risked revealing the choices of these voters (OSCE/ODIHR 2019b: 25–26). To preserve ballot secrecy, ballots from such small groups of voters should be merged with a larger pool of votes before they are opened and counted.

3.2. Rules for marking ballots

In some countries the rules for marking ballots are strict, allowing only a certain type of mark to be used. Strict rules are often justified by the need to prevent vote buying and to protect secrecy, although it is not clear whether these rules are making a meaningful contribution to meeting these aims. At the same time, strict rules may lead to a higher number of invalid ballots. In the 2011 elections in Poland, for example, the only valid mark on the ballot was a cross. International observers noticed that votes were regarded as invalid because the cross was not placed correctly or because voters had used another symbol to show their preference. This led to 680,524 invalid votes, or 4.52 per cent of all votes cast (OSCE/ODIHR 2012: 20).

A better practice which minimizes invalid votes is to permit all ballots where the voter’s intention is clearly expressed. Ballots marked in a way which reveals a voter’s identity should still be invalidated.

3.3. Counting and tallying votes

The transparency of ballot counting and the tallying of votes is especially important in environments where accusations of malfeasance are common and trust in electoral integrity is low. Good practices to ensure transparency include allowing partisan and non-partisan observers to follow the process and publicize the results from each step. For example, where counting takes place at polling stations, posting the results outside the polling station and sharing them with observers is a good practice. Another good practice is to periodically share the results of vote tallying with observers at the regional and national levels.

Where ballots are counted in locations other than polling stations (such as counting centres or higher-level election administration bodies), the security of ballots in transit needs to be ensured. Election contestants should be reassured that the integrity of election materials is preserved in transit, and they should be allowed to accompany the ballots to the counting facility.

With the Covid-19 pandemic, countries where votes were counted and tallied at large counting centres had to reconsider this model due to the need to maintain social distancing (and consequently the need for even more spacious premises) and to avoid large gatherings of staff in confined spaces.

4. Post-election period

The electoral regulations should clearly establish the chain of custody for sensitive election materials such as ballots after the voting results are announced. The packaging, collection, transportation and storage of ballots and other sensitive election materials should be organized in a way that guarantees the security of these materials at all times, especially in environments where trust in electoral integrity is low.

In many countries election results are often disputed, and resolving these disputes may require a re-examination of the ballots, voter lists and other materials. This means that the rules and regulations on the secure storage of election materials should facilitate access to these materials for the purposes of any re-examination ordered by an EMB, a court or another authorized body. In practice, secure storage sites should be chosen to enable such access, and materials should be stored until any election disputes are settled. A longer period may be warranted in order to maintain public confidence in election integrity.

The legal framework should specify how long ballot papers are to be stored and who is responsible for their storage and eventual destruction. There should also be clear rules for authorizing access to and the handling of ballots in storage. Ballot papers and other election materials that are eventually marked for destruction should be disposed of in environmentally friendly ways.

The post-election phase of the process offers opportunities to analyse any shortcomings and learn lessons from them. EMBs and other responsible authorities are commonly required to prepare reports on elections, which may also be used to initiate a discussion of changes to the legal framework and electoral practice. For example, the National Audit Office of Sweden noted in its 2020 report the large number of ballot papers required to conduct general elections and recommended that the government ‘initiate a broad review of the ballot paper system to determine how an alternative ballot paper system could be designed for future elections’.

References

ACE Electoral Knowledge Network, ‘Civic and voter education’, [n.d.], <https://aceproject.org/ace-en/topics/ve/default>, accessed 16 November 2024

—, ‘Serial numbers on ballots’, 10 June 2010, <https://aceproject.org/electoral-advice/archive/questions/replies/912993749>, accessed 16 November 2024

Botswana, Republic of, Act No. 38/1968, 17 May 1968

Center for Civic Design, ‘Vol. 01: Designing Usable Ballots’, Field Guides to Ensuring Voter Intent, 4th edn (2018a), <https://civicdesign.org/fieldguides/designing-usable-ballots>, accessed 16 November 2024

—, ‘Vol. 02: Writing Instructions Voters Understand’, Field Guides to Ensuring Voter Intent, 4th edn (2018b), <https://civicdesign.org/fieldguides/writing-instructions-voters-understand>, accessed 16 November 2024

—, ‘Vol. 03: Testing Ballots for Usability’, Field Guides to Ensuring Voter Intent, 4th edn (2018c), <https://civicdesign.org/fieldguides/testing-ballots-for-usability>, accessed 16 November 2024

—, ‘Vol. 104: Designing Vote by Mail Envelopes', Field Guides to Ensuring Voter Intent, 4th edn (2018d),), <https://civicdesign.org/fieldguides/104-designing-vote-at-home-envelopes>, accessed 16 November 2024

Democracy in Action, ‘Early Elections to the Assembly of Kosovo, 11 June 2017: Election Observation Report’, 2017, <http://kdi-kosova.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/150-dnv-raporti-perfundimtar-zgjedhjet-2017_eng.pdf>, accessed 16 November 2024

Elklit, J., ‘Is voting in Sweden secret? An illustration of the challenges in reaching electoral integrity’, Paper prepared for presentation at the International Political Science Association World Congress, Brisbane, Australia, 21–25 July 2018, 26 June 2018, <https://pure.au.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/128529565/Brisbane_paper_on_secret_voting_26062018.pdf>, accessed 16 November 2024

International Republican Institute, ‘2003 Nigeria Election Observation Report’, 1 April 2003, <https://www.iri.org/resources/nigerias-2003-presidential-and-national-assembly-elections>, accessed 16 November 2024

Kaiser, S., Social Media: A Practical Guide for Electoral Management Bodies (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2014), <https://www.idea.int/publications/catalogue/social-media-practical-guide-electoral-management-bodies>, accessed 16 November 2024

Kyrgyz Republic, Konstitutsionnyi zakon Kyrgyzskoi Respubliki o vyborakh Prezidenta Kyrgyzskoi Respubliki i deputatov Zhogorku Kenesha Kyrgyzskoi Respubliki, N 68 [Constitutional Act No. 68 of the Kyrgyz Republic on Elections of the President of the Kyrgyz Republic and Deputies of the Parliament of the Kyrgyz Republic], 2 July 2011, <https://shailoo.gov.kg/ru/konstitucionnye-zakony-kr/konstitucionnye-zakony-kr/O_vyborah_Pr-1913/>, accessed 16 November 2024

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE/ODIHR), ‘Republic of Poland: Parliamentary Elections, 9 October 2011’, OSCE/ODIHR Election Assessment Mission Report, 18 January 2012, <https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/7/5/87024_0.pdf>, accessed 16 November 2024

—, ‘Kyrgyz Republic: Parliamentary Elections, 4 October 2015’, OSCE/ODIHR Election Observation Mission Final Report, 28 January 2016, <https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/a/c/219186.pdf>, accessed 16 November 2024

—, ‘Republic of Austria: Presidential Election, Repeat Second Round, 4 December 2016’, OSCE/ODIHR Election Expert Team Final Report, 17 March 2017, <https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/6/6/305766.pdf>, accessed 16 November 2024

—, ‘Sweden: General Elections, 9 September 2018’, ODIHR Election Expert Team Final Report, 21 November 2018, <https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/6/2/403760.pdf>, accessed 16 November 2024

—, ‘Greece: Early Parliamentary Elections, 7 July 2019’, ODIHR Election Assessment Mission Final Report, 13 December 2019a, <https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/d/f/442168.pdf>, accessed 16 November 2024

—, ‘Republic of North Macedonia: Presidential Election, 21 April and 5 May 2019’, ODIHR Election Observation Mission Final Report, 21 August 2019b, <https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/1/7/428369_1.pdf>, accessed 16 November 2024

Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, ‘Application to initiate a monitoring procedure to investigate electoral fraud in the United Kingdom’, Document AS/Mon (2007) 38, [n.d.], <https://assembly.coe.int/CommitteeDocs/2008/electoral_fraud_UK_E.pdf>, accessed 16 November 2024

—, ‘Resolution 1590 (2007): Secret ballot – European code of conduct on secret balloting, including guidelines for politicians, observers and voters’, 23 November 2007, <https://assembly.coe.int/nw/xml/XRef/Xref-XML2HTML-en.asp?fileid=17609&lang=en>, accessed 16 November 2024

Reidy, T. and Buckley, F., ‘Ballot paper design: Evidence from an experimental study at the 2009 local elections’, Irish Political Studies, 30/4 (2015), pp. 619–40, <https://doi.org/10.1080/07907184.2015.1100802>

Reynolds, A., Reilly, B. and Ellis, A., Electoral System Design: The New International IDEA Handbook (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2005), <https://www.idea.int/publications/catalogue/electoral-system-design-new-international-idea-handbook>, accessed 16 November 2024

Swedish National Audit Office, The electoral process – secrecy of the ballot, accuracy and acceptable time frame, 15 January 2020, RIR 2019:35, <https://www.riksrevisionen.se/download/18.2008b69c18bd0f6ed3f2a11a/1579078768266/RiR_2019_35_ENG.pdf>, accessed 16 November 2024

United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), Resolution 217A (III), Universal Declaration of Human Rights, A/RES/217(III), 10 December 1948

—, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 999 United Nations Treaty Series 171, 19 December 1966

United States Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, ‘ADA requirements: Effective communication’, 28 February 2020, <https://www.ada.gov/resources/effective-communication/>, accessed 16 November 2024

United States Election Assistance Commission, Election Infrastructure Government Coordinating Council and Subsector Coordinating Council’s Joint COVID Working Group, ‘The Importance of Accurate Voter Data When Expanding Absentee or Mail Ballot Voting’, [n.d.], <https://www.eac.gov/sites/default/files/electionofficials/vbm/Accurate_Voter_Record_041720.pdf>, accessed 16 November 2024

—, ‘Health and Safety at the Polling Place’, 28 May 2020, <https://www.eac.gov/sites/default/files/electionofficials/inpersonvoting/Health_and_Safety_at_the_Polling_Place_052820.pdf>, accessed 16 November 2024

Van der Staak, S. and Wolf, P., Cybersecurity in Elections: Models of Interagency Collaboration (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2019), <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2019.23>

Venice Commission, European Commission for Democracy through Law, Code of Good Practice in Electoral Matters: Guidelines, Explanatory Report and Interpretive Declarations (Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe, 2002), <https://www.venice.coe.int/images/SITE%20IMAGES/Publications/Code_conduite_PREMS%20026115%20GBR.pdf>, accessed 16 November 2024

—, ‘Revised Code of Good Practice on Referendums’, Document CDL-AD(2022)015, 20 June 2022, <https://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/default.aspx?pdffile=CDL-AD(2022)015-e>, accessed 16 November 2024

Wolf, P., Nackerdien, R. and Tuccinardi, D., Introducing Electronic Voting: Essential Considerations, Policy Paper (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2011), <https://www.idea.int/publications/catalogue/introducing-electronic-voting-essential-considerations>, accessed 16 November 2024

About the authors

Vasil Vashchanka holds a Master of Laws degree from Central European University (Budapest, Hungary) and is currently an external researcher at the Research Centre for State and Law of Radboud University (Nijmegen, the Netherlands), where he focuses on corruption and political finance. Vasil worked on rule of law and democratization at the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (Warsaw, Poland) between 2002 and 2012 and was a programme officer with International IDEA’s Electoral Processes team (Stockholm, Sweden) between 2012 and 2014. Vasil has served as a consultant on legal and electoral issues for the OSCE, the Council of Europe and the United Nations. He has taken part in international election observation missions, authored expert reviews of legislation and published academically.

Kate Sullivan is an experienced electoral administrator who has followed US electoral issues since her first degree, in US politics. She has worked at the Australian and British electoral commissions, at International IDEA and for the British Foreign Office. She has led UN electoral assistance teams in Libya, Myanmar, Papua New Guinea, the Republic of Moldova, Sierra Leone and Yemen.

© 2025 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members.

With the exception of any third-party images and photos, the electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0>.

Design and layout: International IDEA

DOI: <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2025.4>

ISBN: 978-91-7671-882-7 (PDF)

ISBN: 978-91-7671-883-4 (HTML)