The Impact of the 2023 Wildfires on Subnational Elections in Canada

Natural Hazards and Elections Series

Executive summary

The increased frequency and severity of natural hazards in recent years presents challenges to political institutions worldwide. For democracies, emergencies such as wildfires can substantially affect an electoral management body’s (EMB) capacity to administer free and fair elections. In this case study, two jurisdictions in Canada are examined—Alberta and the Northwest Territories—whose general elections were affected by wildfires in 2023.

The findings show how governments can respond differently when faced with the same type of natural hazard. Alberta’s EMB, Elections Alberta, chose to expand voting opportunities for electors who were displaced, while the Northwest Territories’ EMB, Elections NWT, requested that legislators postpone the election to give time to the evacuated residents to return. Our analysis of these institutional responses points to the influence of factors such as the jurisdiction’s contextual circumstances, the severity and length of the natural hazard, rurality of the area, and pre-existing legislation and policy frameworks.

Lessons from these cases demonstrate several best practices: taking care to support the well-being of electoral staff; clear, up-to-date communications; having a standardized approach to emergency preparedness; cross-agency collaboration; and having in place the necessary legislation or powers to facilitate timely EMB responses. Overall, the experiences of Alberta and the Northwest Territories illustrate that when administering elections during natural hazards, EMBs must implement solutions that best fit their specific circumstances. Ultimately, there is no single best practice or ideal approach, but rather a range of emergency response options that may be appropriate depending on circumstances.

Introduction

There has been an increase in the intensity and frequency of weather-related natural hazards in recent years (UNDRR 2024).1 For example, data from the United States shows that in the 1980s natural hazards occurred on average 3.3 times per year across the country, whereas in the past decade that number has exceeded 17 (USAFacts Team 2024). Natural hazards can have catastrophic economic, social and political impacts. This includes impacts on electoral integrity.

All stages of the electoral cycle can be impacted by natural hazards, including the pre- and post electoral stages. However, the threat to elections is most acute when a hazard (such as an extreme weather event) coincides with campaigning or the day of the election. This may lead to election postponement (James and Alihodžić 2020), voter disenfranchisement (Zelin and Smith 2023), or even increased corruption (Birch and Martínez i Coma 2023). In the face of natural hazards, it is much harder for EMBs, as public administrative bodies, to fulfil their roles and responsibilities. When hazards occur, election administrators might be forced to pivot away from their regular electoral management strategies to ensure democratic elections continue to take place.

In this case study, we examine the effects of natural hazards on EMBs and the administration of elections by drawing on the example of two Canadian jurisdictions. In the summer of 2023, wildfires affected much of Canada, with major cities under the haze of smoke, and towns evacuated from coast to coast. For the Canadian province of Alberta and one of the country’s territories, the Northwest Territories, wildfires occurred during the time of general (subnational) elections, posing significant challenges for their administration and access to ballots. By documenting their election experiences during the exogenous shocks, the case study outlines lessons learned for practitioners and scholars to better prepare and respond in an age where natural hazards are becoming more frequent and intense (UNDRR 2024).

1. Methods

To prepare this case study secondary sources were collected, including media articles and reports from the election agencies. To provide additional explanatory insight and obtain details not published in the public record or in official reports, two interviews were conducted with the Chief Electoral Officers of Elections Alberta and Elections Northwest Territories between 13 September and 1 October 2024. Interviews were semi-structured, lasting up to one hour, and were conducted virtually via Microsoft Teams. Questions were fact-based. They probed challenges posed by the wildfires, the time frame for decision-making processes, factors considered when making decisions in response to the fires, specific impacts on different aspects of the election, impacts on cost, lessons learned, and key reforms or changes (see the Annex for the questionnaire). Interviews served to bolster the information already collected and to provide key reflections from the EMBs’ leaders.

2. Natural hazard context

In Alberta, summer wildfires are a regular occurrence. The 2023 wildfires, however, burned an unprecedented 2.2 million hectares (Derworiz 2024) or approximately 22,000 km2, affecting six electoral districts in the province. This means that of Alberta’s total land area—635,000 km2 (Statistics Canada 2022)—3.46 per cent was affected. While precautions had been put in place such as requiring permits for burning, additional firefighter training and moving firefighting equipment, dry conditions suggested the 2023 wildfire season would be especially bad (The Weather Network 2023). In addition to local states of emergency, a province-wide state of emergency was declared on 6 May 2023 (Markov 2023). At least 48 communities were affected by these fires, and over 38,000 Albertans were evacuated, including 13 whole communities, due to the threat of either the wildfire moving in or smoke (Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre 2023). While there were no reported civilian deaths (Jones et al. 2024), at least one firefighter died as a result of the fires (Aziz 2023).

Meanwhile, 303 wildfires in the neighbouring Northwest Territories burned an unprecedented 4.1 million hectares of forest (41,000 km2), displacing up to 70 per cent of the population at their height (Dunbar 2024; Northwest Territories 2024; Ridgen 2024). Of the territory’s total land area, 1,172,000 km2 (Government of Canada 2017), this represented 3.5 per cent. Although local fire crews had been deployed early in anticipation of a difficult wildfire season, it became necessary to also bring in fire crews from other countries and provinces due to the fires’ unprecedented severity (O’Neill and Otis 2023). A territory-wide state of emergency was called on 15 August 2023 (DeLaire 2023). The Behchoko-Yellowknife and Hay River wildfires caused over CAD 60 million in insured damages (Insurance Bureau of Canada 2023). The damage was so severe in the hamlet of Enterprise that 90 per cent of the community was destroyed (CBC News 2023).

As in Alberta, a summer wildfire season is common, but extreme drought conditions, high temperatures and high winds resulted in the most severe fires the territory had ever seen (Northwest Territories 2024). In both cases it was commonly reported that the unprecedented scale and severity of the fires was linked to climate change (Derworiz 2024). The scope and magnitude of the wildfires were exacerbated by increased heat waves and drier forests which increase the risk of fires but also extend the wildfire season. This problem is intensified in Northern Canada and Arctic areas, where the rate of global warming is possibly several times higher than the rate elsewhere in the world, causing unusually warm and dry spring and summer seasons (Shingler 2023).

3. Electoral management and constitutional context

Alberta and the Northwest Territories are both subnational jurisdictions within Canada. Alberta is one of 10 Canadian provinces, while the Northwest Territories is one of the country’s three territories. Although the differences between a province and territory are constitutionally meaningful within the context of Canadian politics, the distinction is less relevant to our discussion of election management. In 2023, both were scheduled to have a general election to elect representatives to their respective legislatures. Details about both elections, as well as the administrative decisions that were made about the wildfires, are discussed more fully below.

Alberta

The province’s general election took place on 29 May 2023, after a 28-day election period which began on 1 May 2023. The date was determined in accordance with the province’s Election Act, which states that Alberta’s fixed election date is to occur in the fourth year after the last general election, on the last Monday in May (Elections Alberta 2024).

Because it was a general election, all 87 electoral districts were up for contest. In Alberta, one candidate is elected per electoral district, meaning that its Legislative Assembly has the same number of seats as it does electoral districts. Since Alberta has a single-member plurality electoral system, an election occurs in every electoral district between that district’s candidates. Elections Alberta, the independent and non-partisan EMB responsible for managing provincial elections in Alberta, is therefore responsible for administering the election in each electoral district.

Elections Alberta’s wildfire response

Wildfires in Alberta occurred throughout the election period and impacted many communities across the province. While Alberta’s legislated wildfire season begins on 1 March and ends on 31 October every year (Alberta 2024b: s. 17(1)), the province-wide state of emergency that was declared on 6 May 2023 coincided with the province’s general election (1–29 May).

Under the province’s Election Act, when the Chief Electoral Officer believes an emergency or natural hazard might impact the opening of, or voting at, a voting place, they have the power to move it to a different location on the same day or to change its opening time on that day (Alberta 2024a: s. 4(3.1)).

However, it is important to note that the law does not allow the Chief Electoral Officer to adjourn voting in an electoral district past election day. If adjourning past election day—what is formally called ‘discontinuing’ the election—is required, then the Chief Electoral Officer must apply to a judge of the Court of King’s Bench (the Superior Trial Court for the province). If the court approves the application to discontinue the election in that district, then the election in that district must occur within six months of the application date (Alberta 2024a: s. 4(3.5–3.6)).

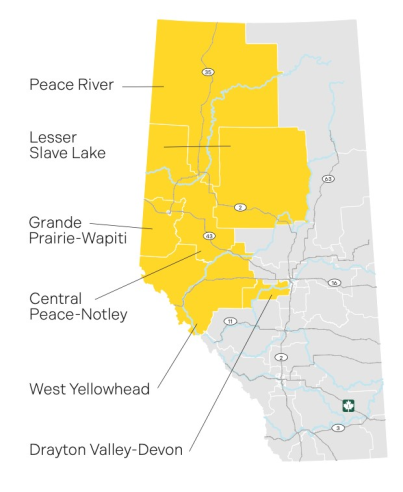

While Elections Alberta reports that there were many calls to discontinue the election (Elections Alberta 2024: 109), it did not apply to discontinue the election in any of the 87 electoral districts. Even though six electoral divisions—Drayton Valley-Devon, Athabasca-Barrhead-Westlock, Central Peace-Notley, Lesser Slave Lake, Peace River, West Yellowhead—could have been postponed, doing so would have left approximately 163,214 voters without any kind of representation in Alberta’s legislature until a by-election could be held (Petrowsky 2024).

Instead, the EMB and its staff acted to ensure that voters who were displaced by the wildfires had access to voting places or ballots. This involved Returning Officers—the individual in charge of the administration of an election in an electoral district—consulting with emergency personnel and community leaders to inform their decision making. Doing so helped Returning Officers in the affected electoral districts to identify potential risks and provide voters with different options for how to vote (Elections Alberta 2024: 113). While advance voting was a substantial part of this, Elections Alberta also opened access to requesting a special ballot—a write-in ballot that does not have the names of the candidates running in the electoral division, which allows electors to vote by mail. Special ballots were distributed (a) by using Alberta Forestry (the department in charge of wildfire management and prevention) to deliver ballots to emergency personnel; and (b) by utilizing mail services, which created new opportunities at evacuation centres to vote (Petrowsky 2024).

Northwest Territories

The territory’s general election took place on 14 November 2023, after a 30-day election period which began on 16 October 2023. This is notable as the original election period was supposed to start on 4 September 2023, with election day on 3 October 2023, but was postponed due to the wildfires. Therefore, while Alberta is a case example of an EMB administering the election through the natural hazard, the case of the Northwest Territories shows an alternative strategy to postpone elections until emergency conditions subside.

Elections in the Northwest Territories are planned and administered by a non-partisan and independent EMB: Elections Northwest Territories (Elections NWT). During a general election, Elections NWT is responsible for informing the public about voting procedures and electoral rights, appointing and training election officers, reviewing the financial reports of candidates, maintaining voter lists, enforcing election law, supervising the ballot casting process, reporting election results and recommending changes to election legislation (Elections NWT n.d.).

All 19 electoral districts, and thus all seats in the Legislative Assembly of the Northwest Territories, were up for contest. While only one candidate is elected per electoral district—since the Northwest Territories also follows a single-member plurality electoral system across all its electoral districts—it should be noted that the Northwest Territories does not have political parties (White 2001), making campaigns entirely about the candidates as individuals.

Elections NWT’s wildfire response

Evacuations commenced in May 2023 and ended in mid-September, with the vast majority of those displaced being evacuated out of territory. As mentioned, displacement affected some 70 per cent of the territory’s total population (41,070—Statistics Canada 2024). Up until July, the EMB had contingency plans in place for implementing the original schedule, that is four years since previous polling. That election period was to start on 4 September 2023, with election day on 3 October. Contingency plans involved setting up temporary polling locations in evacuee shelters (Elections NWT 2024: 19). If an electoral district was more severely impacted, Elections NWT was prepared to withdraw the writ of election in that district.

Because the wildfires continued into August—impacting the capital city of Yellowknife, as well as regional centres like Hay River and Fort Smith, among others—the Chief Electoral Officer began looking at possible options to delay the entire territorial election. On 13 August, discussions began with the Clerk of the Legislative Assembly and a review of what was permitted under the territory’s legislation occurred the next morning.

While the Chief Electoral Officer has the authority under the territory’s Elections and Plebiscites Act to recommend to the Commissioner that the writ of the election for that district be rescinded (with a new writ required within three months), they do not have the power or authority to alter the date of the election for a district absent of the withdrawal of the writ, or to delay the entire election. Nor did the legislation allow for Elections NWT to open polling stations in evacuee shelters or other locations outside of the territory. Due to these legal limitations, the Chief Electoral Officer (with the support of the Clerk of the Legislative Assembly) requested that a new bill be drafted by the territory’s Department of Justice which would change the date of the territorial election, notwithstanding the fixed date otherwise set out in the Act (Elections NWT 2024).

This recommendation came on 16 August 2023, the day after the entire territory had come under a state of emergency. A post-election report by Elections NWT highlights two reasons for delaying the election. First, since polling locations could not be set up outside of the territory, there were concerns that evacuees might not have the required identification needed to vote by absentee ballot. A second concern was logistical issues caused by the wildfires—such as the difficulty of setting up returning offices in affected communities, the (in)ability to send election materials to electoral districts that were not evacuated, and the safety of election workers.

While waiting for the bill to be passed, Elections NWT set up operations at the headquarters of Elections Alberta, to the south. This was in case Elections NWT needed to mobilize to administer elections in some electoral districts. However, as noted, by 28 August 2023 the Legislative Assembly unanimously passed the bill to postpone the election day, thus giving additional time for conditions to improve throughout the territory. Additionally, on 29 August the Chief Electoral Officer delivered instructions that the displacement or absence of a voter from their electoral district would not be regarded as a change to their residence, even if the residence has been destroyed. This was to ensure that voters would not be disenfranchised because of the fires (Elections NWT 2024; Dunbar 2024). By 11 September 2023 the staff of Elections NWT had returned to their offices in the territory. The final evacuation order in the territory was lifted on 18 September (Elections NWT 2024: 20). This gave electoral staff more than a month to prepare before the start of the new election period (16 October until election day on 14 November 2023).

It is noteworthy that Elections NWT also researched various alternatives should the evacuation order continue. These included the use of an electronic absentee ballot. Remote online ballots had already been offered to absentee voters (in this and the previous, 2019, territorial elections) so this voting channel could have been expanded if needed.

4. Measures taken to enable conduct of elections

The previous section demonstrates that while the magnitude of the wildfires differed, in both Alberta and the Northwest Territories the respective legal framework impacted how the EMB could respond. Whereas the wildfires and election laws in Alberta led to a situation where Elections Alberta’s staff focused on ensuring electors had access to voting opportunities and voting places, the situation in the Northwest Territories led to a legislative change to postpone the entire territorial election.

The next focus of this case study is on the measures taken by both jurisdictions to manage the following five topics: planning for the election before and during a natural hazard; voter registration; the campaign period; election day; and the information environment.

Planning for the election

Both EMBs developed risk management frameworks and undertook resilience-building in anticipation of the wildfires. In this context, risk management is the act of creating processes for identifying potential problems the EMB might face, while resilience-building consists of strengthening the EMB so that it can continue to fulfil its administrative duties even when emergencies occur (Alihodžić 2023: 11). EMBs may adopt different crisis management responses to a similar issue based on the circumstances of the election, the relevant legislation and the resources available. Elections Alberta, for example, established two ‘alternate returning office teams’ that could be deployed in any electoral district where circumstances prevented the on-ground team from fulfilling their duties (Elections Alberta 2024: 24). One of these teams was sent to the West Yellowhead electoral district to provide training to local staff which had been delayed due to the wildfires. As mentioned, Elections NWT originally set up contingency plans for evacuees to vote while displaced in shelters, before shifting to postponement.

Also key in planning is up-to-date information, which was difficult to obtain as the situations evolved rapidly in both contexts. In Alberta, for example, the information the agency was receiving from Alberta Forestry and Alberta Emergency Management was not sufficient to determine voting area impact and had to be filled in by an internal global information system (GIS) team. The team consisted of four staff members who worked on overlays and maps, turning the information the EMB was receiving into workable data for timely planning decisions (Petrowsky 2024). In the Northwest Territories, concern quickly turned into an evacuation order giving a majority of the territory’s residents 36 hours to leave. Improved information in the case of future natural hazards was noted as a top consideration (Dunbar 2024).

Voter registration

Both jurisdictions have designated approaches on how to conduct voter registration ahead of, and during, elections.

Alberta provides five periods in which an elector can either register to vote or update their information: any time between election events, during a provincial voter registration campaign (‘enumeration period’), during a revision period (the time between the issue of the writs of election and prior to the start of advance voting) or at a voting place—up to and including on polling day itself. Finally, if an elector registered during a previous election, they do not need to register again unless they wish to update their information (Elections Alberta 2024: 52). This flexibility means the impacts of wildfires on voter registration are less severe, or costly to rectify—so long as they register ahead of time or can get to a voting place on a voting day, then eligible Albertans can register. Providing ways for electors to get to voting places (or alternative ways to register if they are unable to in-person on a voting day) is nevertheless crucial for electors who have not registered ahead of time. Since between 80 and 90 per cent of permanent electors in Alberta were already registered and only 14 per cent of those who voted chose to register at the polls (Petrowsky 2024), it is unlikely that the wildfires had a major impact on voter registration in Alberta.

In the Northwest Territories, electors can register outside of election periods within the territory, but most tend to do so during elections (Elections NWT 2024: 18). Elections NWT sent cards in the mail in May 2023 to encourage individuals to register. Registration can be done online or in-person and can occur both before and during election periods—as in Alberta, electors can vote at polling stations even if they are not registered beforehand (Northwest Territories 2007: s. 177–78). Elections NWT’s report about the administration of the 2023 territorial election and our interview with Chief Electoral Officer (Dunbar 2024) suggest that the wildfires did not cause any major issues for voter registration.

Voter information campaign

Elections Alberta manages the campaign period via a Returning Officer who administers the election in each electoral division. The EMB’s central headquarters then coordinates province-wide electoral communications and publicity while supporting the local needs of each returning office (Elections Alberta 2024: 83). Elections Alberta erects road signs with key milestones relating to the administrative aspect of the campaign and updates them throughout the campaign. These include messages about hiring, advance poll dates, and when election day will be. Some of these signs could not be updated because either the wildfires blocked access to them, or they were in areas under evacuation. While the EMB also ran newspaper, television, social media and radio advertisements, it is notable that this mainstay of physical advertisements was lost.

To provide information to electors and to support recruitment efforts in electoral districts that were impacted by wildfires, Elections Alberta utilized targeted social media and online advertisements on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), Instagram, Snapchat, TikTok, YouTube, Quora, Native Touch, Google Display, Google Search and Bing Search. It also placed billboards and conducted media interviews (Elections Alberta 2024). Targeted radio advertisements were used in six electoral districts (see Figure 1), which included essential voter information such as ways to vote in those districts and changes to polling locations.

Public information through a variety of channels proved to be very important during Alberta’s wildfire emergencies, as false information about both wildfires and election rules was also in circulation (Roley 2023; Weingarten 2023). The wildfires also affected the campaigns of several candidates and party leaders in Alberta, some of whom had responsibilities both to run a campaign and to assist evacuation efforts (Boynton 2023).

By contrast, the campaign period in the Northwest Territories avoided many disruptions because the entire election was postponed.

Election day

Election day in Alberta took place on 29 May 2023, with 1,216 voting places and 4,714 voting stations throughout the province. In response to the ongoing wildfires, access to special ballots was expanded to electors that were displaced by a natural hazard or emergency, as well as to emergency personnel and firefighters that were outside of their electoral district (Elections Alberta 2024: 104, 111). The EMB also utilized mobile voting in evacuation centres. Unlike most other voting channels, the province’s election laws do not require identification to be shown for mobile voting (mobile voters instead sign a declaration stating their address and that they have not already voted). This has clear advantages in averting disenfranchisement during emergency and evacuation, when voters might not have all their documents with them. The trade-off between security and accessibility in voter identification is currently a major debate in other countries like the USA. However, in the Canadian context, there is currently no evidence of widespread voter fraud when electors have the option to use an affidavit as proof of their identification.

Some voting places were relocated in advance of, or on, election day because of the wildfires and voter displacement. For example, in the electoral district of Lesser Slave Lake, evacuees from Chipewyan Lake could vote at the relocated voting place in Wabasca-Desmarais or at Northern Lakes College—Slave Lake Campus if they instead relocated to Slave Lake (Elections Alberta 2024: 114). In summary, Elections Alberta’s wildfire response broadly extended the ways to vote across the province (specifically by special ballot) while also providing more specific extensions (such as mobile voting or relocating voting places) in affected areas.

By comparison, there were seven ways for electors to cast a ballot during the Northwest Territories’ 2023 postponed territorial election period: casting an absentee ballot online, casting a mail-in absentee ballot, voting in the returning office of their electoral district, voting at a mobile poll, voting at an advance poll, voting at a returning office in a regional centre (a multi-district poll), and voting on election day.

The Northwest Territories face challenges to the administration of elections—unrelated to wildfires—which make multiple voting channels advantageous in any case. The territory has several rural and remote areas that experience logistical challenges in receiving election materials. A recent paper on online absentee voters in the territory explains that ‘[s]everal communities can only be accessed by airplanes, and some [communities with road access] are inaccessible when river crossings are not solidly frozen in the fall months. In addition, the northern location of the territory means it can experience unpredictable weather, including heavy fog and blizzards, which can complicate ballot and election delivery’ (Goodman, Hayes and Dunbar 2024: 90). Given their rurality, Canada’s three territories are exceptional in that Canada Post, the national postal service, does not guarantee delivery times. Therefore, while postponing the election prevented further complications caused by the wildfires, the territory still has environmental and geographical factors that continuously impact the operations of Elections NWT.

Information environment

Disinformation campaigns are not a new phenomenon in elections (Garnett and James 2020: 117) but have changed substantially in the last decade with the shift to social media and other online platforms. During the 2023 wildfires in Canada, false information circulated about both the wildfires and the administration of elections. Some popular narratives claimed that all wildfires were started by arsonists, that they were state-driven cases of arson, that they were started by elites to control people, or that ecoterrorism was the cause of the wildfires; in fact, investigators concluded that only 0.01 per cent of the total land affected by wildfires in 2023 in Canada was arson-related (Russill et al. 2024; Laucius 2024). In addition to these broader false narratives about the wildfires, false information also circulated that directly impacted the elections.

In Alberta, photos of wildfires from 2016 were widely shared via Facebook, producing confusion about which communities were currently affected (Weingarten 2023). Elections Alberta also had to clarify how its scanners and tabulators work to count hand-marked votes, in response to baseless claims circulating online to the effect that its voting technology was being pre-loaded in favour of one political party (Roley 2023).

In the Northwest Territories, by comparison, false information was focused mostly on the proximity of wildfires to communities and the speed at which they were spreading (Tran and Semple 2023). Because this false information circulated prior to the postponed election period, it likely did not affect electoral administration. However, Elections NWT does note in its post-election report that ‘election misinformation is an unfortunately growing issue’ and that while most cases are not impactful, the institution has begun to use videos to promote itself as the trusted source of election information (Elections NWT 2024: 12).

At least one study shows that the presence of online disinformation during elections has a negative effect on the public’s perceptions of electoral fairness (Mauk and Grömping 2023), while another demonstrates that when there are unsubstantiated claims about voter fraud that reduce confidence in electoral integrity, fact-checking does not easily mitigate their effects (Berlinski et al. 2023). Therefore, EMBs must seriously consider how false information about the administration or rules of an election may impact public perceptions. During natural hazards, ensuring EMBs are trusted sources of information may especially be important in cases where alternative ways of voting are offered to accommodate emergency circumstances.

5. Cost of elections

Despite the unexpected effects of the wildfires, both EMBs managed to keep costs relatively close to their intended budget, noting small additions to the total cost of the election.

While Elections Alberta did not officially track additional costs caused by the wildfires, the extra expenses incurred seemed modest in relation to the election budget (Petrowsky 2024), which exceeded CAD 36 million in 2023. Previous budgets amounted to approximately CAD 24.4 million in 2019 and CAD 19 million in 2015 (Elections Alberta 2020). Looking at a breakdown of costs from 2019 to 2023 we see that the largest increases were in the areas of freight and postage, contract services, rentals for the Returning Officer’s office, technology services, and election materials and supplies (see Elections Alberta 2024 for a breakdown). Election delivery in 2023 also had to contend with a population increase of 8.7 per cent and an inflation increase of 14.9 per cent from 2019 (Elections Alberta 2024).

Specifically, extra budget was approved for advertising across traditional social media sources to inform electors whose voting places were being moved. Extra costs were also incurred for staffing, including hiring election officers to replace those displaced from the fires as well as having additional trainers and IT support to help some districts hire and train new staff. Finally, there were added costs in transporting ballots—extra staff were hired to transport special ballots and ballot boxes to evacuation centres to help facilitate voting and then return the completed ballots to Elections Alberta (Petrowsky 2024).

In the case of the Northwest Territories, the 2023 election cost approximately CAD 50,000 more than the 2019 general territorial election, amounting to just under CAD 992,000. While some of this increase may have been attributable to inflation and the rising costs of election materials, especially post pandemic, there were specific expenses that increased because of the postponement caused by the wildfires. Printing costs were one of these increases. At the time of the fires, ballots had not yet been printed and the EMB had to reprint a lot of election materials on temporarily relocating their operations to Elections Alberta. Additionally, costs to ship materials such as voter information letters changed, and the delays caused by the colder climate in the territory blocked road access to many communities. The colder temperatures in the territory also meant that ferries were out of the water and thus Elections NWT had to rely more heavily on on-air cargo—a more costly form of transportation. In addition to printing and transportation costs, additional fees for procurement were incurred (Dunbar 2024). Overall, Elections NWT experienced a modest increase in costs, which is perhaps not surprising since the EMB must frequently be nimble in its election delivery given the rural and remote nature of the territory. For example, because the postal service does not guarantee delivery times across the territory, Elections NWT must often pivot to alternative modes of transportation, including snowmobiles and helicopters.

6. Election results and turnout

In Alberta, the election resulted in a United Conservative Party (UCP) government, with 52.6 per cent of the vote. Danielle Smith, leader of the Alberta UCP, was re-elected to a second term. Turnout in Alberta was at 60.5 per cent in 2023, lower than the 67.5 per cent in 2019, but higher than the 53 per cent in 2015 (Elections Alberta 2023).

The Northwest Territories operates under a consensus government—there are no political parties and the elected officials select who will serve as Premier. After the 2023 election, R. J. Simpson was chosen as the Premier (Northwest Territories 2023). Turnout in this election was down slightly at 52.54 per cent compared to 54 per cent in 2019 but higher than the 44 per cent turnout in 2015 (Elections NWT 2024, 2019b, 2015).

To estimate the potential effects of the wildfires on turnout, turnout from the previous 2019 and 2023 elections was collected per electoral district. The electoral district boundaries were overlayed on a map of wildfire danger, provided by the Interactive Canadian Wildland Fire Information System (Natural Resources Canada 2023), set to the date of the scheduled election for each jurisdiction and the predominant coding of danger for that electoral district at the time. This method is approximate but provides some indication of how much the wildfires impacted the region.

In Alberta, election day saw 66 per cent of electoral districts predominately in the ‘extreme’ range of threat, with another 30 per cent in the ‘very high’ range. A comparison of turnout changes from 2019 to 2023 for each of the Alberta electoral districts does not show any statistically significant difference in mean turnout between those electoral districts at a very high versus extreme fire threat level (difference is –.22, p>0.1).

A similar comparison of turnout in Northwest Territories is difficult since by the time the scheduled election date arrived, the fire threat levels lowered substantially, with most of the province at a low or moderate level of threat. Furthermore, the number of electoral districts in the territory is considerably smaller (19 electoral districts), making statistical tests impractical.

7. Reform

Several legal and regulatory reforms were either made at the time of the wildfires or identified as being necessary in the future, after the impact of the fires on the election was assessed. The month of May, when Alberta’s elections are typically held, tends to be the emergency season in the province for wildfires. Recognizing this, and to minimize risk exposure, Elections Alberta recommended to Alberta’s legislature that the fixed election date should no longer be in May. Before Elections Alberta’s post-election report was given to the Alberta legislature, the Alberta Government proceeded to pass Bill 21, which moves the fixed election date to the third Monday in October every four years. This bill will take effect in 2027.

While no reforms have yet been made in the Northwest Territories, one stands out as necessary to consider. As explained earlier, standalone legislation was required to delay the territorial election. Thus, a recommendation to be better prepared for future elections would be to expand the emergency powers of the Chief Electoral Officer of Elections NWT so that they could decide to postpone the election without the Legislative Assembly needing to pass legislation during a rapidly evolving natural hazard. In 2023, it was unclear if the assembly would be able to meet for an emergency session to pass the required legislation before its scheduled dissolution. Providing standalone powers to the Chief Electoral Officer in cases of emergencies or natural hazards could be an effective way to avert this kind of uncertainty. While there may be objections to giving an EMB such power, given the checks and balances in Canada’s stable democracy, the risk posed to free and fair elections is low.

8. Main findings and lessons learned

Both Chief Electoral Officers and their respective teams learned lessons from administering an election either during, or immediately following, the wildfires. These findings and lessons are relevant to any government or EMB facing the administration of an election during an exogenous shock related to climate change. Below, we list five key lessons from the two jurisdictions.

A top concern for both agencies was safeguarding the well-being of staff and voters. EMBs have a duty of care to do everything in their powers to keep core stakeholders out of harm’s way, making it a top priority that influenced decision making. In some cases, election staff needed to be relieved of their duties to tend to personal and familial emergencies relating to the wildfires. Knowing how to work with sudden changes—while supporting staff—was an important takeaway from 2023.

A second takeaway is the need for clear and up-to-date communications—which enables an EMB to adapt to unfolding circumstances. An important part of this is the sharing of reliable and timely data. In the case of Alberta, the information that Elections Alberta received from forestry and emergency management agencies was not sufficient to assess operational impacts in the tight timeframes required; sometimes decisions needed to be made in a few hours. As noted above, a special segment of the EMB—the Global Information System (GIS) Team—worked to fill gaps and translate the information into workable data that allowed officials to make decisions and inform voters of the same. This included tracking evacuations and estimating displacements to keep stakeholders safely informed. Elections NWT likewise experienced challenges with being kept fully informed by its counterparts. Part of the reason for this was that previous wildfires did not behave in the same way as the ones in 2023, which made it difficult for all government agencies to determine what would occur next, or the appropriate response. Such unpredictability is an increasing challenge that governments and EMBs will have to adapt to as climate crises and natural hazards continue to change and grow in magnitude.

Third, a standardized approach to emergency preparedness is required. A primary takeaway for Elections Alberta was the need to have a standardized contingency plan in place. In the case of Elections NWT, contingencies relate to the transport and logistical challenges of the terrain outlined above. While each natural hazard may require its own unique contingency plan based on the circumstances of the situation, having some standard options in place can help EMBs think through what they could consider as climate-related emergencies arise.

Fourth, cross-agency collaboration was often key to the foregoing considerations—either within the jurisdiction or across adjacent jurisdictions. In Alberta, for example, collaboration with another government department, Alberta Forestry, facilitated preparation, distribution and collection of special ballot applications for firefighters in Northern Alberta. In the Northwest Territories, due to an abrupt evacuation at only 36 hours’ notice, collaboration was more clearly seen across agencies outside of the territory. Upon notice of the evacuation, staff drove 18 hours to reach Elections Alberta, where they set up temporary offices. Elections Alberta offered key support by providing Elections NWT with office space and printing supplies. Among Canada’s other provincial EMBs, Elections New Brunswick offered to support communications, while Elections Ontario, Elections Nova Scotia, and Elections Newfoundland and Labrador provided advice, documents and contingency plans from past incidents, as did the federal agency, Elections Canada. Such cross-agency collaboration was crucial in supporting Elections NWT in their preparations for the upcoming election and other core operations.

A fifth and final lesson relates to changes in electoral legislation or an EMB’s powers to permit rapid and decisive natural hazard responses. In Canada, the powers of Chief Electoral Officers vary dramatically by province and territory. In some, like the province of Ontario, the Chief Electoral Officer has the authority to change the day of the election, while in others, like the Northwest Territories, the Chief Electoral Officer does not. In the latter case, vesting the EMB with this power might be an important step in emergency preparedness. Likewise, modifications to legislation in Alberta could have provided the agency with even greater flexibility in its response. For example, rules on access to special ballots could conceivably be made less restrictive.

These five lessons from the experiences of Alberta and the Northwest Territories serve as important case examples for EMBs that must administer elections during natural hazards like wildfires.

References

Alberta, Province of, ‘Election Act’ (amended 2022), Office Consolidation, 30 May 2024a, <https://kings-printer.alberta.ca/1266.cfm?page=E01.cfm&leg_type=Acts&isbncln=9780779847785>, accessed 6 December 2024

—, ‘Forest and Prairie Protection Act’ (amended 2022), Office Consolidation, 30 May 2024b, <https://kings-printer.alberta.ca/1266.cfm?page=F19.cfm&leg_type=Acts&isbncln=9780779847815>, accessed 6 December 2024

Alihodžić, S., Protecting Elections: Risk Management, Resilience-Building and Crisis Management in Elections (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2023), <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2023.44>

Aziz, S. ‘In the line of fire: Firefighters face perilous conditions amid record season’, Global News, 2 August 2023, <https://globalnews.ca/news/9869441/canada-firefighter-deaths-dangers-wildfires/>, accessed 6 December 2024

Berlinski, N., Doyle, M., Guess, A. M., Levy, G., Lyons, B., Montgomery, J. M., Nyhan, B. and Reifler, J., ‘The effects of unsubstantiated claims of voter fraud on confidence in elections’, Journal of Experimental Political Science, 10/1 (2023), pp. 34–49, <https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2021.18>

Birch, S. and Martínez i Coma, F., ‘Natural disasters and the limits of electoral clientelism: Evidence from Honduras’, Electoral Studies, 85 (2023), 102651, <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2023.102651>

Boynton, S., ‘As wildfires upend Alberta election campaign, here’s where the race stands’, Global News, 14 May 2023, <https://globalnews.ca/news/9695646/alberta-election-wildfires-smith-notley-west-block/>, accessed 6 December 2024

Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre. ‘Canada Report: 2023 Fire Season’, September 2023, <https://ciffc.ca/sites/default/files/2024-03/03.07.24_CIFFC_2023CanadaReport%20%281%29.pdf>, accessed 6 December 2024

CBC News, ‘Enterprise, N.W.T., “90 per cent gone” after wildfire ravages community’, 15 August 2023, <https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/enterprise-damage-wildfire-1.6936652>, accessed 6 December 2024

DeLaire, M., ‘Parts of the Northwest Territories to remain under state of emergency into October’, CTV News, 19 September 2023, <https://www.ctvnews.ca/climate-and-environment/parts-of-the-northwest-territories-to-remain-under-state-of-emergency-into-october-1.6568553>, accessed 6 December 2024

Derworiz, C., ‘Wildfires in Alberta burned 10 times more area in 2023 than the five-year average’, CBC News, 5 January 2024, <https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/wildfires-in-alberta-burned-10-times-more-area-in-2023-than-the-five-year-average-1.7075263>, accessed 6 December 2024

Dunbar, S., Chief Electoral Officer of Elections NWT, authors’ online interview, Canada, 13 September 2024

Elections Alberta, ‘Provincial Electoral Divisions’, December 2017, <https://www.elections.ab.ca/uploads/2019Boundaries_ALBERTA_11X17.pdf>, accessed 6 December 2024

—, ‘2019 General Election: A Report of the Chief Electoral Officer’, March 2020, <https://www.elections.ab.ca/uploads/Volume-1-2019-Provincial-General-Election-Report.pdf>, accessed 6 December 2024

—, ‘Provincial Results: Provincial General Election May 29, 2023’, 23 June 2023, <https://officialresults.elections.ab.ca/orResultsPGE.cfm?EventId=101>, accessed 6 December 2024

—, 2023 Provincial General Election Report (Edmonton, Alberta: Elections Alberta, 2024), <https://www.elections.ab.ca/uploads/2023-Provincial-General-Election-Report.pdf>, accessed 6 December 2024

Elections NWT, ‘About Elections NWT’, [n.d.], <https://www.electionsnwt.ca/en/about-elections-nwt>, accessed 6 December 2024

—, ‘2015 Official Voting Results’, 21 December 2015, <https://www.electionsnwt.ca/sites/electionsnwt/files/2015-12-21_official_voting_results_of_the_2015_general_election_englishweb.pdf>, accessed 6 December 2024

—, ‘Electoral Districts of the NWT (ED Map), 21 March 2019a, <https://www.electionsnwt.ca/sites/electionsnwt/files/all_nwt_ed_2019.pdf>, accessed 6 December 2024

—, ‘Territorial General Election 2019: Official Results Report’, 25 October 2019b, <https://www.electionsnwt.ca/sites/electionsnwt/files/nwt_elections_7528_official_results_report_eng_web_0.pdf>, accessed 6 December 2024

—, ‘Territorial General Election 2023 Official Results Report’, January 2024, <https://www.electionsnwt.ca/sites/electionsnwt/files/2023_nwt_general_election_results_report_en.pdf>, accessed 6 December 2024

Garnett, H. A. and James, T. S., ‘Cyber elections in the digital age: Threats and opportunities of technology for electoral integrity’, Election Law Journal, 19/2 (2020), pp. 111–26, <https://doi.org/10.1089/elj.2020.0633>

Goodman, N., Hayes, H. A. and Dunbar, S., ‘Absentee Online Voters in the Northwest Territories: Attitudes and Impacts on Participation’, in D. Duenas-Cid et al. (eds) Electronic Voting. E-Vote-ID 2024. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Vol. 15014 (Cham: Springer, 2024), <https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-72244-8_6>

Government of Canada, ‘Northwest Territories’ territorial symbols’, 15 August 2017, <https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/services/provincial-territorial-symbols-canada/northwest-territories.html>, accessed 6 December 2024

Insurance Bureau of Canada, ‘Behchoko-Yellowknife and Hay River wildfires cause over $60 million in insured damage’, 20 November 2023, <https://www.ibc.ca/news-insights/news/behchoko-yellowknife-and-hay-river-wildfires-cause-over-60-million-in-insured-damage>, accessed 6 December 2024

James, T. S. and Alihodžić, S., ‘When is it democratic to postpone an election? Elections during natural disasters, COVID-19 and emergency situations’, Election Law Journal, 19/3 (2020), pp. 344–62, <https://doi.org/10.1089/elj.2020.0642>

Jones, M. W., Kelley, D. I., Burton, C. A., Di Giuseppe, F., Barbosa, M. L. F., Brambleby, E., Hartley, A. J., Lombardi, A., Mataveli, G., McNorton, J. R., Spuler, F. R., Wessel, J. B., Abatzoglou, J. T., Anderson, L. O., Andela, N., Archibald, S., Armenteras, D., Burke, E., Carmenta, R., Chuvieco, E., Clarke, H., Doerr, S. H., Fernandes, P. M., Giglio, L., Hamilton, D. S., Hantson, S., Harris, S., Jain, P., Kolden, C. A., Kurvits, T., Lampe, S., Meier, S., New, S., Parrington, M., Perron, M. M. G., Qu, Y., Ribeiro, N. S., Saharjo, B. H., San-Miguel-Ayanz, J., Shuman, J. K., Tanpipat, V., van der Werf, G. R., Veraverbeke, S. and Xanthopoulos, G., ‘State of wildfires 2023–2024’, Earth System Science Data, 16/8 (2024), pp. 3601–85, <https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-16-3601-2024>

Laucius, J., ‘Flame wars: Carleton researcher on team tracking how misinformation spread in last year’s wildfires’, Ottawa Citizen, 3 August 2024, <https://ottawacitizen.com/news/local-news/flame-wars-carleton-researcher-on-team-tracking-how-misinformation-spread-in-last-years-wildfires>, accessed 6 December 2024

Markov, K., ‘Alberta wildfire season 2023: How does it compare?’, CTV News, 10 May 2023, <https://edmonton.ctvnews.ca/alberta-wildfire-season-2023-how-does-it-compare-1.6391711>, accessed 6 December 2024

Mauk, M. and Grömping, M., ‘Online disinformation predicts inaccurate beliefs about election fairness among both winners and losers’, Comparative Political Studies, 57/6 (2023), pp. 1–34, <https://doi.org/10.1177/00104140231193008>

Natural Resources Canada, ‘Interactive map’, 28 May 2023, <https://cwfis.cfs.nrcan.gc.ca/interactive-map?zoom=2¢er=-140875.62861366407%2C1091512.145556278&month=5&day=28&year=2023#iMap>, accessed 6 December 2024

Northwest Territories, Government of the, ‘Elections and Plebiscites Act’, 7 January 2007, <https://www.justice.gov.nt.ca/en/files/legislation/elections-and-plebiscites/elections-and-plebiscites.a.pdf>, accessed 6 December 2024

—, ‘Premier R. J. Simpson’, 20 December 2023, <https://www.gov.nt.ca/en/premier-rj-simpson>, accessed 6 December 2024

—, ‘Independent reviews of wildfire and emergency response for 2023 wildfire season underway’, 15 February 2024, <https://www.gov.nt.ca/en/newsroom/independent-reviews-wildfire-and-emergency-response-2023-wildfire-season-underway-0>, accessed 6 December 2024

O’Neill, N. and Otis, D., ‘Military deploys 350 soldiers to Northwest Territories, 68 per cent of population evacuated’, CTV News, 21 August 2023, <https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/military-deploys-350-soldiers-to-northwest-territories-68-per-cent-of-population-evacuated-1.6527811>, accessed 6 December 2024

Petrowsky, L., Chief Electoral Officer of Elections Alberta, authors’ online interview, Canada, 1 October 2024

Ridgen, M., ‘“Highway out was on fire”: Calls for inquest grow into “slow” N.W.T fire response’, Global News, 5 February 2024, <https://globalnews.ca/news/10267109/wildfire-nwt-inquest-2023/>, accessed 6 December 2024

Roley, G., ‘Election technology misinformation spreads as Alberta heads to polls’, AFP Canada, 25 May 2023, <https://factcheck.afp.com/doc.afp.com.33FY4KT>, accessed 6 December 2024

Russill, C., Bridgman, A., Hayes, H. A., Khoo, M., Alrasheed, G., Tollefson, H., Ross, C. and Peterson, L., Flame Wars: Misinformation and Wildfire in Canada’s Climate Conversation (Montreal: Re.Climate/Centre for Media, Technology and Democracy/Climate Action Against Disinformation, 2024), <https://foe.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/2024-Final-REPORT%E2%80%93Wildfire-Misinformation-01d-2.pdf>, accessed 6 December 2024

Shingler, B., ‘What’s driving the powerful wildfires in the Northwest Territories’, CBC News, 17 August 2023, <https://www.cbc.ca/news/climate/northwest-territories-wildfires-1.6939337>, accessed 6 December 2024

Statistics Canada, ‘Focus on Geography Series, 2021 Census of Population: Alberta, Province’, 16 December 2022, <https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/as-sa/fogs-spg/Page.cfm?Lang=E&Dguid=2021A000248&topic=1>, accessed 6 December 2024

—, ‘Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population: Northwest Territories [Territory]’, 2 August 2024, <https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&SearchText=Northwest%20Territories&DGUIDlist=2021A000261&GENDERlist=1,2,3&STATISTIClist=1&HEADERlist=0>, accessed 29 October 2024

Tran, P. and Semple, J., ‘How does wildfire misinformation affect communities in N.W.T. and B.C.?’, Global News, 20 August 2023, <https://globalnews.ca/news/9908441/wildfire-misinformation-chaos-northwest-territories-b-c/>, accessed 6 December 2024

United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), GAR Special Report 2024: Forensic Insights for Future Resilience Learning from Past Disasters (Geneva: UNDRR, 2024), <https://www.undrr.org/media/100220/download?startDownload=20241106>, accessed 6 December 2024

—, ‘Why are disasters not natural?’, [n.d.], <https://www.undrr.org/our-impact/campaigns/no-natural-disasters>, accessed 6 December 2024

USAFacts Team, ‘Are major natural disasters increasing?’, 6 September 2024, <https://usafacts.org/articles/are-the-number-of-major-natural-disasters-increasing/>, accessed 6 December 2024

Weather Network, The, ‘2023 is off to a dry start, and Alberta’s fire danger rating is rising’, 27 April 2023, <https://www.theweathernetwork.com/en/news/weather/severe/2023-is-off-to-a-dry-start-and-albertas-fire-danger-rating-is-rising>, accessed 6 December 2024

Weingarten, N., ‘False wildfire and election information is thriving online. Here’s how you can tackle it’, CBC News, 22 May 2023, <https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/wildfire-election-tackling-misinformation-1.6847916>, accessed 6 December 2024

White, G., ‘Beyond Westminster: The new machinery of subnational government: Adapting the Westminster model: Provincial and territorial cabinets in Canada’, Public Money & Management, 21/2 (2001), pp. 17–24, <https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9302.00255>

Zelin, W. A. and Smith, D. A., ‘Weather to vote: How natural disasters shape turnout decisions’, Political Research Quarterly, 76/2 (2023), pp. 553–64, <https://doi.org/10.1177/10659129221093386>

Annex A. Interview questions on wildfires and the election

Decision-making process

- What were the biggest challenges [EMB] faced regarding the wildfires?

- When responding to challenges caused by the wildfires, what was the time frame for [EMB]’s decision-making processes?

- Which factors did [EMB] consider when making decisions about the election in response to the wildfires? How were these factors weighed against each other?

Specific issues

- Did the wildfires impact some ridings more than others? If yes, in which ways?

- Did any of these communities already have challenges before the wildfires that may have compounded the impact?

- Did the wildfires impact voter registration? If yes, in which ways?

- Did inaccurate information impact the administration of the election? If yes, in which ways?

Cost of the election

- Did the wildfires impact the cost of the election? If yes, in which ways?

- How much was the total cost of the administration of the election?

Concluding questions

- What are the major takeaways or ‘lessons that you learned’ from the election?

- Are there any reforms or changes that were implemented in response to the wildfires that the agency plans to keep? Likewise, is there anything the agency would have done differently?

- Is there any other information about the wildfires that would be helpful to know for our case study?

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Stephen Dunbar (Chief Electoral Officer, Elections NWT) and LaRae Petrowsky (former Acting Chief Electoral Officer, Elections Alberta) for their responses during their interviews and for taking the time to answer our questions. We also thank Samantha Curry, a research assistant at Queen’s University in Canada. We appreciate the support of the International IDEA staff and thank them for their role in the publishing process.

About the authors

Valere Gaspard is a PhD candidate in the School of Political Studies at the University of Ottawa, and a Research Fellow at Western University and Trent University’s Leadership and Democracy Lab. His research projects focus on Canadian politics, satisfaction with democracy, elections and electoral management bodies. The views of the author do not reflect those of any employer.

Holly Ann Garnett is the Class of 1965 professor of leadership and an associate professor of Political Science at the Royal Military College of Canada. She is cross-appointed faculty at Queen’s University Canada and an honorary research fellow at the University of East Anglia, the United Kingdom. Garnett is co-director of the Electoral Integrity Project, a global network of academics and practitioners that engages in empirical research, publicly accessible data collection and stakeholder engagement on issues relating to election quality around the world.

Nicole Goodman is an associate professor of Political Science at Brock University, Ontario. Her research examines civic participation and governance with a specific focus on digital technology. Her work has appeared in leading journals and is frequently consulted by domestic and international governments, not-for-profit organizations and parliamentary committees.

Contributors

Erik Asplund, Senior Advisor, Electoral Processes Programme, International IDEA.

Sarah Birch, Professor of Political Science and Director of Research (Department of Political Economy), King’s College London.

Ferran Martinez i Coma, PhD, Associate Professor, School of Government and International Relations at Griffith University, Queensland.

- This International IDEA series uses the term ‘natural hazards’ in place of ‘natural disasters’ due to concerns raised by the United Nations about the latter term. Specifically, natural hazards (like wildfires) only become a disaster when damage caused to communities is due to inadequate protection—which is a human-made, not a ‘natural’ dimension of the problem. On this model, Disaster = hazard [whether natural or human-made] + exposure + vulnerability (see UNDRR n.d.).

© 2025 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members.

With the exception of any third-party images and photos, the electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0>.

The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on maps in this publication, do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by International IDEA or its Member States.

This case study is part of a project on natural hazards and elections, edited by Erik Asplund (International IDEA), Sarah Birch (King's College London) and Ferran Martinez i Coma (Griffith University).

Design and layout: International IDEA

DOI: <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2025.2>

ISBN: 978-91-7671-878-0 (PDF)

ISBN: 978-91-7671-879-7 (HTML)