Imagining Democratic Futures: South Asia Foresight Report 2025

Discussion Paper, February 2025

Democracy is in trouble. The most recent Global State of Democracy (GSoD) Report shows that electoral turnout has been steadily trending downwards for two decades, while the number of elections marked by riots or protests has steadily increased. South Asia has been no exception to this trend—but in 2024 the subregion also saw two of the world’s most dramatic departures from the status quo: Sheikh Hasina’s abdication and the surprise election of Anura Kumara Dissanayake in Sri Lanka.

Which way might South Asian democracy be heading? Which global or regional forces are likely to constrain democratic expansion and where are the spaces for action? What can be done to ensure that South Asia in 2040 will be more democratic than it is today? To answer these and other questions, International IDEA and the Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA) convened the Democracy in South Asia Outlook Forum in Colombo, Sri Lanka, on 28–30 November 2024, bringing together a multidisciplinary group of experts for two and a half days of discussion and collaboration.

This document is the result of those efforts. The primary focus of the workshop was the careful creation of four scenarios describing how democracy in South Asia might develop over the next 15 years: Continuation; Disciplined improvement; Decline; and Transformation. These scenarios are not intended to be predictive, but to extrapolate existing trends and possibilities into visions of possible futures that allow us to see today’s challenges in a new light—and to provide inspiration for action.

In the continuation scenario, South Asia is politically fragmented and dominated by strong authoritarian rulers and populists. Wealth inequalities have continued to grow and pollution has rendered large urban centres dangerous. The rights framework is deprioritized and public finances are dependent on international finance. The relationship between citizens and the state has changed, and horizontal social bonds have largely replaced the central government as a source of welfare.

In the disciplined improvement scenario, democracy stabilizes as South Asian countries collaborate on migration and climate change policies. Civic engagement grows as a new generation of leaders rises from public protests following several natural disasters. Regional alliances are strengthened, including bilateral ties between India and Pakistan, embodied through knowledge-transfer initiatives and a regional catastrophe fund set up for climate-displaced populations. While the fund’s impact is partial, it reinforces regional unity and efforts to address inequalities.

In the decline scenario, democracy has deteriorated in every respect in South Asia and states are under crony-capitalist control. The surveillance and censorship industry is a significant source of employment and local ecological breakdown appears to be irreversible for the foreseeable future. Electoral participation is higher than in the 2020s, but voting is now primarily just a means of securing political patronage. A weakened West is no longer interested in lending support for human rights protections or Westminster-style parliamentary democracy, and the dream of a strong South Asian regionalism is now a thing of the past.

In the transformation scenario, South Asia has become a centre for democratic innovation, embracing deliberative democracy to enhance citizens’ well-being and the environment. Governments invest in inclusive policies, cultivating civillages (integrated city and village spaces), which bridge urban–rural divides. The region transforms into a ‘solarpunk society’ whereby sustainability and equality are prioritized over extractive and capitalistic values in preventing ecological collapse. Youth-led ethical tech start-ups and expanded civic space strengthen grassroots governance, intergenerational dialogue, and participatory decision making.

The full report delves more deeply into these scenarios and the paths that connect them to the present day. The report then asks: what can we make of these four disparate visions of South Asia’s democratic futures? And more importantly: what can be done to ensure that in 20 years South Asia is more democratic than it is today? Through engagement with these scenarios in greater depth and asking critical questions, this report aims to provide the beginning of an answer and begin a broader conversation.

Democracy is in trouble. The most recent Global State of Democracy (GSoD) Report shows that electoral turnout has been steadily trending downwards for two decades (International IDEA 2024). Over the same period, the number of elections marked by riots or protests has steadily increased. In 2024, a year in which 1.7 billion people went to the polls, one in three were living in a country where International IDEA’s GSoD Indices data showed the quality of elections was inferior to five years before. In other words, democratic institutions around the world are delivering less and political action outside of official institutions is increasing as a result.

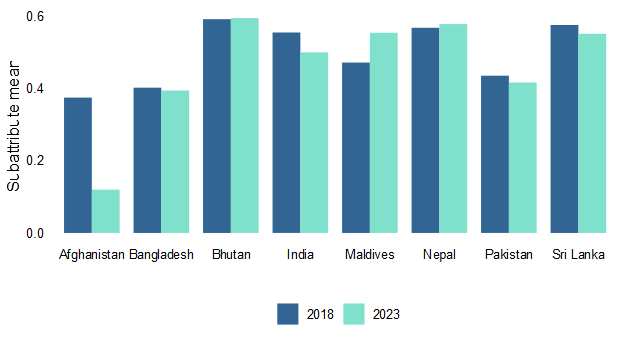

South Asia is no exception to this global trend. While there are bright spots in the Maldives and Nepal, most people in the region live in a state where overall democratic performance is weaker than five years before. Afghanistan is the most striking case but all three regional giants—India, Pakistan and Bangladesh—have seen declines over the five years between 2018 and 2023 (see Figure 1).

Nonetheless, the 2024 global election super-cycle year has been full of dramatic departures from the status quo (International IDEA n.d.a). In line with the theme of citizens losing patience with democratic ‘business as usual’, two of the most noteworthy events in global democracy in 2024 took place in South Asia. Sri Lankan voters rejected the presidential candidates of the parties that have ruled the country since independence. Instead, they favoured the leader of a party that within living memory had been a revolutionary Marxist organization that fought two armed insurgencies against the Sri Lankan state (International IDEA n.d.b). Bangladesh is, at the time of writing, undergoing a period of radical institutional change after mass protests forced its long-time autocratic President, Sheikh Hasina, to abdicate and flee the country (International IDEA n.d.c).

These events and more raise questions about how democracy in South Asia might develop in the years to come, what government reformers can do to reverse the trend of slow decline and how civil society activists and citizens should engage with each other to revitalize civic life. Which global or regional forces are likely to constrain democratic expansion and where are the spaces for action? What can be done to ensure that we will be able to say in 15 years that South Asia is more democratic than it is today?

To answer these and other questions, International IDEA and the Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA) convened the Democracy in South Asia Outlook Forum in Colombo, Sri Lanka, on 28–30 November 2024. The forum brought together a multidisciplinary group of experts for two and a half days of foresight and futures activities to collectively formulate answers to these questions. The participants came from Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

The workshop was facilitated and guided by two foresight specialists, Daniel Riveong, principal owner at Plural Futures, and Ammaarah Nilafdeen, Next Generation Foresight Practitioner Fellow with the School of International Futures. This report is illustrated throughout with photographs by Milan Rai.

The primary focus of the workshop was the careful creation of four scenarios to describe how democracy in South Asia might develop along four ‘lines of flight’: Continuation, Disciplined Improvement, Decline and Transformation.1 Before delving into the end-products of the workshop, there follows a discussion of the methods used to produce them.

The question of how democracy might evolve is not an easy one to answer. Governance and social organizations are inherently complex systems. Societies evolve under the interactions of more tangible factors, such as climate change and technological advancement, as well as intangible factors such as values and ideas, and multiple factors in between.

To address these challenges, the forum applied the foresight approach to help participants grapple with the complexities of the forum’s questions in a more systematic way. Foresight, as a set of practices, is an ‘organised, systematic way of looking beyond the expected to engage with uncertainty and complexity’ (Gov.UK 2021). Its tools provide a systems-based approach to better understand the interplay between the different forces that can shape democracy in a region.

Through the foresight process, participants in the forum engaged in a sense-making exercise to better understand how current and emerging factors—from climate change to geopolitical shifts—might create unexpected pathways for how democracy, societies and polities develop in the region. The purpose is not to predict the future with a certain amount of accuracy, but to use the future as a lens for understanding how to make better choices today.

In the workshop, the participants collectively assembled four different scenarios to describe four possible South Asian futures in the year 2040. Participants described these scenarios in detail and then worked backwards from that future vantage point to develop a logical storyline from existing trends, institutions and social systems.

Framework for scenario development

The definition of democracy used by the GSoD Initiative is public control over decision making and decision makers, and equality in the exercise of that control. While this was used as an initial frame for understanding and conceptualizing democracy at the forum, participants were not bound by it. In order to broaden perspectives and allow for both more holistic and more precise conceptualizations of the meaning of democracy, the work process began by inviting participants to discuss how they understand democracy and governance in their local and regional contexts. These discussions helped to highlight that South Asia’s unique dynamics create different meanings and potentialities for concepts such as democracy and governance. They also ensured that participants interpreted the scenarios, which use archetypes (see Annex A) such as ‘collapse’ or ‘transformation’, through their own lenses.

Next, the participants began collectively to develop the scenarios through a multi-step process that involved: (a) exploring the key factors that shape democratization and governance in the region; (b) identifying which factors in the region could move most in unexpected ways; and (c) developing distinct paths in which these factors could take democracy in the region under archetype scenarios of continuation, collapse, transformative or disciplined improvement.

As part of the first step, participants were presented with 21 factors—trends, forces and thematic areas—that influence the dynamics of the region across social, political, economic and other critical dimensions. These factors might be external to democracy itself but are certain to shape the quality and character of governance in the decades to come.

The factors were adjusted and new ones added based on the collective discussions, and then prioritized. Participants then assessed the potential long-term influence of the factors and the level of uncertainty regarding how they might develop. Essentially, they were asked to find the ‘wild card’ factors that might lead to radically different paths for the development of democracy and governance in the region.

Through this collective process, five high-influence, high-uncertainty factors were chosen: climate change and environmental degradation; migration; geopolitics; civic space; and big tech and artificial intelligence (AI).2 Participants used the scenario archetypes to imagine how these factors could lead to radically different outcomes for the region—from a ‘collapse’ into quarrelling, oppressive and environmentally degraded states to a ‘transformation’ into vibrant, inclusive democracies capable of coping with climate-related and geopolitical challenges.

How could democracy look in 2040?

South Asia is politically fragmented and dominated by strong authoritarian rulers and populists. While on the surface little appears to have changed and wealth inequalities have continued to grow as before, the level of pollution in the region’s large urban centres has led muckraking local media to label them ‘unliveable’. The rights framework and its enforcement in court have been deprioritized. Erstwhile rights activists have reoriented themselves to supplying necessities and supporting those who need to migrate to survive.

Central governments continue to provide public services, but public finances are pressured by an international brain drain, the health stresses of poor environmental conditions and—in Pakistan, Sri Lanka and elsewhere—continued dependence on restrictive International Monetary Fund (IMF) and Chinese financing. Electoral turnout has declined significantly at the national level, as voters first vent frustration over and then display a lack of interest in the restricted policy choices available to governments so reliant on foreign capital.

Internal migration has shifted the relationship between citizens and the state, resulting in stronger connections to local institutions and weaker connections to the national government. This includes wealthy urban enclaves where local governments are better-resourced, but also largely rural, once-marginalized regions that are home to ethnic, religious and tribal communities and the erstwhile rural poor. Given the retreat of human rights as a governing legal framework, outcomes in these communities are mixed. Traditional ties based on caste, ethnicity or religion mean that stronger horizontal bonds between citizens enable them to collectively fill the gaps left by a retreating central government, but it also means that the rights of women, LGBTQIA+ people, and the poorest of the poor are frequently derogated.

How did we get there?

This scenario begins with more of the same: governments discuss climate change and measures to tackle pollution but fail to come up with bold enough measures, leaving individuals to take responsibility for adaption, such as through solar panels on rooftops, the use of air purifiers to manage the smog in Kathmandu and Delhi, and air conditioning to cope with the heat of Karachi and Dhaka (Rathore and Mittal 2024).

By 2035, pollution in the major cities across the region has reached critical levels. The local governments in Delhi and Islamabad respond competently by attempting to copy best practices from other major cities around the world, including introducing congestion zones. These wider measures fail without support from national governments and, by the end of the year, major cities are relying on lower-cost measures that shift the burden to the individual, such as mask mandates for schoolchildren. Civic engagement thus becomes more horizontal and localized. These environmental challenges are increasingly seen as beyond the power of national governments and citizens seek to work around them rather than address them head on.

With no adequate global climate finance agreement in place, the private sector and industry take the lead on prevention and mitigation efforts. The mining of minerals critical to the green transition and related extractive industries are major boons to the Bhutanese, Indian and Nepalese economies, and to Bengali engineers who rival the Dutch for finding innovative solutions to protect low-lying flood zones against rising sea levels (Shampa et al. 2023). A lack of democratic accountability, however, means that environmental harms are widely shared but economic gains are not.

This attitudinal shift to local adaptation over national political action causes rights-based non-governmental organizations and democratic reformers to lose their political bearings, and governments are largely eager to sideline actors that they often view as foreign-funded interlopers. The space for civic engagement shrinks accordingly, but not at a dramatic speed. The sources of funding dry up for civil society organizations, and registration procedures and tax filings become progressively more onerous. A more multipolar global order has the effect of reducing geopolitical pressure on the countries in the region, but an increased dependence on international finance produces the same outcomes for democratic politics. Governments must balance domestic policy priorities with those of foreign financiers and creditors. The United States is less engaged with the region, so trade and economic ties between India and China increase, and an amicable resolution to their border dispute their border dispute

The overlapping issues of local pollution and climate change fuel the rise of the region’s most radical green presidential candidate in Sri Lanka and a push for a South Asian Green New Deal (Song et al. 2023). Despite catching the world’s attention, the candidate loses to a populist Sinhalese nationalist in a hotly contested campaign. The winning candidate follows a model that has proved to be a political winner across the region: confronting climate-related and economic challenges through a return to traditional, ostensibly pre-colonial patriarchal values (Sharma 2023). The widespread abstention by ethnic and religious minorities, which view building local and regional democracy as more important than national elections, also contributes to the winning candidate’s success.

A resulting decrease in consumption reduces the stress on local environments, but the accompanying change in legal norms and interpretation deprioritizes civil liberties and individual rights at the expense of the group. Traditional forms of tribal and religious adjudication gain popularity as law-bound courts become more and more the domain of wealthy elites.

In the absence of bold global political leadership on climate change, governments turn to privatization and public–private partnerships to attract the international investment needed to modernize infrastructure and shift away from fossil fuels (Gabor 2021). This strategy demonstrates some level of success and enables more work and life outside of the subcontinent’s polluted major cities, but the dependence on foreign private capital limits local sovereignty and sends significant locally produced wealth abroad for decades to come (Dafermos, Gabor and Michell 2021Dafermos et al. 2021

In 2040, the highly educated workers most attractive to Chinese, European and US companies continue to go abroad. Many cannot leave, however, or choose to stay and participate in the beginning of a mass migration in the region from the cities to the relatively depopulated countryside. Lower-income groups, for whom the economic returns of remaining in cities are cancelled out by still-harmful levels of air and water pollution, begin to follow while the wealthiest citizens have the means to transform cities to fit their needs and so remain. As a result, local and regional governments become more important to everyday life than national ones, and a variety of democratic and less than democratic experiments begin to take root across the region.

How could democracy look in 2040?

In 2040, democracy in South Asia is more defined by regional collaboration and resilience amid catastrophic weather events and more intense mass migration. Severe conflicts, social distortions and ethnic tensions have prompted a reassessment of shared policies on migration and climate change. South Asian countries are increasingly collaborating on issues such as safe migration, alleviating the impacts of climate change and curbing technology misuse. This collaboration has extended to strengthening educational policies and engaging with civil society on policy consultations.

Civic engagement has significantly increased through a new generation of leaders that arose from public protests following various natural disasters. Bilateral ties have been fortified among countries such as India and Pakistan, as well as between smaller and bigger nations in a unified regional alliance. South Asian countries have made efforts to pool their resources to establish a catastrophe fund in response to the millions of people made homeless by climate disasters. While only partially delivering on its promises, the fund strengthens civic engagement and the region’s resolve to address economic inequalities.

How did we get there?

The path to 2040 is set in motion by a catastrophic Indian Ocean tsunami that sweeps through the region in 2025, triggering mass displacement and food insecurity. Climate-related disasters such as floods, landslides, desertification and air pollution all intensified, perpetuating internal and cross-border migration.

The tsunami left millions homeless, prompting pressure from civil society and community groups on governments region-wide to address the immediate recovery and rescue project, and to organize disaster management collectively. Eager to assuage public frustrations and prevent a repeat of protests that had previously led to the ousting of leaders in Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, governments come together to tackle the issue collectively (Kenny 2022; International IDEA n.d.c). The coastal cities of Mumbai, Chennai, Colombo and Karachi bore the brunt of the tsunami, leading to an influx of migrants to inland areas and countries such as Nepal. To alleviate the disrupted balance of populations and availability of resources, a number of regional agreements are made to reduce visa restrictions and facilitate freedom of movement. Joint solutions on affordable housing are also initiated to increase local acceptance of migrants. Once-decaying institutions in search of a political purpose such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) prove to be useful vehicles for facilitating these and similar agreements.

However, despite the economic provisions, migrants still struggle to integrate into their new communities due to their limited voting and political rights. Attempts to improve freedom of movement are undermined by surveillance technologies that exacerbate existing inequalities and tensions among minorities in post-conflict settings. The discriminatory application of border technologies is used by some governments to reinforce existing power imbalances, while the mass movement of persecuted minorities triggers communal violence in receiving countries (OSCE 2024; Kugelman 2020).

Recognizing the disproportionate impact of disasters on low-income populations, a regional catastrophe fund is set up supported by both the public and the private sectors. The fund struggles to gain traction, however, as it suffers from similar shortcomings to past international agreements, such as national budget constraints and disagreements on cost sharing (Amnesty International 2024). This lack of progress further undermines public trust in governments as communities feel frustrated by the failure to deliver basic welfare. At the same time, this fuels civic engagement, as activists take governments to court to demand accountability, with some degree of success.

Knowledge transfer initiatives in South Asia start to pick up, facilitating transnational management approaches to climate and migration issues. By 2030, early signals from the 2020s have borne fruit, exemplified by joint India–Pakistan initiatives to combat pollution and initiatives on labour migration governance led by the major powers, as well as innovations such as using fungi to tackle the impacts of food scarcity and to limit carbon dioxide emissions and thus climate change (Averill, Dietze and Bhatnaga 2018; Hussein 2024; IOM 2024

Technological advances in AI are incorporated effectively into climate adaptation projects and play a greater role in simplifying administrative migration processes and flows (IOM n.d.). Conversely, the rapid expansion of generative technologies alongside weak data governance processes ignore civil society and public concerns. Over time, this lack of oversight allows governments and private sector actors to exploit personal data, leading to surveillance states that undermine the civil liberties of populations.

A few countries such as Nepal begin to experiment with feeding the ‘intergenerational trauma and anger management’ discourse into bilateral political consultations to counter widening social group inequalities. Countries with shared histories of conflict exchange reconciliation process best practices, partly supported by the media and civil society through advocacy and public education campaigns.

By 2035, the region is still struggling to recover from the previous decade’s climate-related disasters and the resulting economic downturn. Propelled by financial hardship, citizens and civil society mobilize to demand new results-oriented leadership. From these protests, a new generation of collaborative leaders emerges to implement a new South Asian order rooted in mini-lateralism. The new order prioritizes economic integration and green transitions, capitalizing on deepening trade ties between countries such as China and India to the benefit of the wider region, while still upholding democratic norms.

A concerted effort is made to dismantle the surveillance state by strengthening data governance frameworks and the rule of law. At the same time, a new wave of activists pushes civil society organizations to adopt bolder and more proactive measures to prevent the rise of authoritarian leaders, moving beyond past reactionary responses that addressed the symptoms of shrinking space rather than its root causes (Hutchings and Vannucchi 2022).

By 2040, South Asia has become increasingly active on the international stage. Extended economic cooperation between large and smaller nations has helped proliferate democratic norms. Regional bodies such as ASEAN and SAARC have worked jointly to expand trade networks. Political integration among South Asian countries is further driven by a pilot programme for a common currency and proposals for South Asian citizenship.

How could democracy look in 2040?

Democracy has deteriorated in every respect in South Asia. Electoral processes and checks and balances have long been in steady decline, while a constant erosion of freedoms means that formal civil society is a thing of the past. The mainstream media has fallen under state or crony-capitalist control and journalism is primarily the product of AI language models (Hille 2023). The surveillance and censorship industry, which is a significant source of employment, has defanged once-promising social media networks. Despite the stabilization of the climate at two degrees above pre-industrial levels, local ecological breakdown appears to be irreversible for the foreseeable future. Various marginalized communities across South Asia find themselves playing a dual role as a source of political support for authoritarian governments and the most visible threats to the new social order. Electoral participation is up significantly from the 2020s, but voting is seen more as a means of securing the political patronage of those who rule than an expression of the will of the people.

Climate change has disrupted local ecosystems around the region. Many low-lying coastal regions are now underwater or the soil is too salinized to support agriculture. Inhospitable conditions have emptied the countryside and government make-work schemes constitute a significant proportion of all employment, resulting in entrenched corruption and patrimonial systems. A weakened West is no longer interested in lending support for human rights protections or Westminster-style parliamentary democracy. India has developed its own authoritarian model to compete with China, the regional hegemon. The rest of the region, and especially smaller countries, is caught in a dysfunctional counterbalancing trap between these two giants and the US-led Indo-Pacific alliance. The promising alternative of a strong South Asian regionalism is now a thing of the past.

How did we get there?

The collapse scenario begins with the consequences of climate change across South Asia, which are already visible—in part or in full—today. In the lowlands of Bangladesh, India and Pakistan, this means heatwaves that make if not human existence, then productive economic activity an impossibility throughout their duration (Ullah et al. 2022). At higher altitudes, historic temperature variations have the same effect, albeit less dramatically and with less attention from the international press. People continue to move from the countryside to the cities of the subcontinent as rural life in the absence of air conditioning becomes less stable and more unpredictable. Shifting populations without electoral reform slowly results in parliaments that are less responsive to the general public and more attentive to the priorities of local elites and private sector industry.

Against this backdrop, formal civil society organizations are increasingly seen by regional governments as either a nuisance that distract from the serious issues of security and geopolitics or a hidden tool of foreign influence. Burdensome regulations, invasive audits and police harassment start out as a common but much-condemned practice, before over several years transforming into a shared norm (Surie Saluja and Nixon 2023). Social media platforms and surveillance tools produced by big tech firms largely based outside the region facilitate this state pressure on civil society groups while also automating away an increasing amount of lower-level tech work in Bangalore, Hyderabad and other regional hubs, leading to increased unemployment (Farrell and Berjon 2024Farrell and Berjon 2024).

As international powers become increasingly confrontational and the influence of multilateral organizations declines, geopolitical pressure increases on states both big and small in the region. Relations between India and China become increasingly tense, and the lack of reliable outside mediators or countervailing forces leads the rest of the region to begin to take sides on disparate border, trade and diplomatic disputes. As confrontation becomes the norm in geopolitics, the space for regional cooperation or a revitalized SAARC shrinks. This has deleterious consequences for the region’s ethnic and religious minority populations, which are seen by security-conscious governments less as equal members of the democratic polity and more as potential traitors or double agents.

As the consequences of climate change intensify, typhoons become stronger and their seasons less predictable. Glacial lake outburst floods become more commonplace in the Himalayas, accelerating the migration of rural Himalayan youth that has been ongoing for decades (Mulmi 2024; Shivamurthy 2024). This process leads to a growing crisis of care, as South Asian states step in to care for elderly citizens who were once primarily cared for by their children (Hoang et al. 2015; Yeoh et al. 2020). While this partially alleviates unemployment, the direct employment of a significant part of the populace by local and regional governments results in greater opportunities for vote-buying and patrimonialism, resulting in more durable incumbent politicians.

By this time, international pressure to maintain democratic norms is completely absent, and the region’s dominant economies have progressively drifted towards more authoritarian forms of government. Democratic procedures such as elections and parliaments are now largely for show. Urban unemployment among skilled tech workers has in part been addressed by the development of large private sector companies in regional tech hubs that sell mass surveillance, AI-produced entertainment and ostensible journalism, which are in turn procured by states.

Pockets of exception to this new status quo remain throughout the region. Indigenous peoples, marginalized communities and others regularly scapegoated by populist politicians develop new methods to avoid the watchful eye of the state and carve out new social niches in the changed environments (Tsing 2021). While on paper states maintain complete control, they are frequently paper tigers as the beginnings of new and innovative forms of collective self-government emerge.

Old-fashioned journalism, while no longer mainstream or profitable, persists online and off for those who know how to find it. The normalization of AI-produced online and television content makes organizing and activism at the national level between groups of strangers difficult, but this leads civic-minded individuals to focus much more closely on the local. The collapse of old systems has not filtered down to the level of the individual, and new networks for securing personal freedom and ensuring social solidarity are constantly being developed and reimagined.

How could democracy look in 2040?

South Asia has become the global epicentre of democratic progress. The once fragmented SAARC is revived and united, bringing political stability and sustainable solutions to common challenges such as climate change. Governments invest in inclusive policies and cultivate civillages (integrated city and village spaces), bridging the urban–rural divide and enabling sustainable economic growth and equality. Civic space expands and innovative youth-led start-ups promote the ethical use of tech and AI, fostering intergenerational dialogue and bottom-up approaches to governance.

Institutions are more representative, reflecting the demographics of the region, notably the youth but also other groups that have traditionally been marginalized. A new wave of deliberative democracy sweeps across the region, placing citizens’ well-being and the environment at the core of policy agendas. This shift leads to more equitable and effective forms of governance better suited to tackling existential threats such as climate change (Keutgen 2021). The region becomes reconciled on how natural resources are used, not least by valuing and incorporating Indigenous knowledge into deliberative policymaking (UNDP 2024).

How did we get there?

The journey to 2040 began with growing anti-immigrant sentiment in the West, which fuelled reverse migration in 2026. At the same time, South Asian governments began to incentivize youth to return to the region by expanding financial opportunities and fostering inclusive socio-political environments.

The climate crisis prompted large-scale youth-led demonstrations demanding more action on disaster mitigation, preparedness and response. In Nepal, unprecedented heavy rainfall triggers large-scale protests that inspire similar movements across the region. Meanwhile, populous cities such as Kathmandu and New Delhi become uninhabitable due to deteriorating air quality.

Governments respond to these demands by expanding youth- and gender-inclusive policies (including quotas for elected office), which leads to more representative institutions, particularly at the local level. They also prioritize environmentally sustainable measures to combat air pollution and excessive mineral resource extraction. Governments develop specialized ministries to tap into the expertise and talents of youth, following initiatives led by the Indian Government. This attracts young migrants back from Australia, Canada and the United States through scholarships, tax incentives and support for tech start-ups. Youth-led start-ups increasingly focus on tech innovations that prioritize inclusivity and human-centric solutions. Issues such as corruption, for example, are tackled through crowdsourcing platforms that actively engage with citizens.

By 2035, South Asia has begun its transformation into a ‘solarpunk society’, where nature, technology and social equity coexist harmoniously (Freinacht 2022). Deliberative democracy has become the main form of political organization, empowering communities through inclusive decision-making processes such as citizen assemblies, juries and panels (OECD 2021). These processes also actively engage with indigenous communities to ensure that their insights and traditional practices are incorporated into decision-making processes and climate negotiations.

The region leads the development of civillages, which are piloted in 10 locations to bridge urban and rural divides while integrating cutting-edge technology with grassroots innovations. Civillages are inspired by India’s peri-urbanization and ‘rurban areas’ phenomenon in the 2020s, which evolved from large villages governed by Gram Panchayats (rural local bodies). These seek to build resilient futures that balance economic growth, basic welfare and socio-cultural amenities (Goswami 2018; Chatterjee 2014; Rajendran et al. 2024). This transformation is accompanied by a profound values shift, which moves away from extractive and capitalistic systems in favour of sustainable and egalitarian values (Scott 2023). Over time, these values feed into deliberative processes, leading to more legitimate and effective decision making and bringing far-reaching system reform.

Geopolitical power shifts also lead to greater regional cooperation and economic growth. The declining global influence of the United States and other Western actors creates opportunities for an expansion of trade networks between India and China, as well as among smaller countries such as Bhutan’s influx of Indian trade. At the same time, multilateral collaboration between South Asian states intensifies, leading to a revamp of SAARC to become more solution-oriented regarding common challenges such as climate change. Overall, increased cooperation and economic integration in South Asia lead to development issues and policies becoming less securitized, which enables governments to direct their political energy towards democratization initiatives, such as reshaping electoral processes and strengthening local governance. In 2035, SAARC invests in expanding civillages across South Asia.

By 2040, 40 South Asian civillages are listed as the world’s top liveable cities in the Global Liveability Index (Economist Intelligence Unit 2024Economist Intelligence Unit 2024

What to make of these four disparate visions of South Asia’s democratic futures? While Decline is unambiguously a possible future to be avoided, Continuation and Disciplined Improvement can be considered at best suboptimal means of addressing the challenges currently facing the region. That does not mean that they are without their lessons or even positive examples for dealing with current impasses and crises. Transformation, while no utopia, perhaps provides the most desirable future for most—but what needs to be done, and by whom, to make it a reality?

To revisit the workshop’s initial question: what can be done to ensure that in 20 years South Asia is more democratic than it is today? Various critical questions are set out below that aim to push us towards an answer. They hopefully represent the beginning of a broader conversation about the future of democracy and democratic institutions across the region.

- Given the urgency of the climate crisis and its effects on regional ecosystems and populations, how can democratic institutions be reformed or engineered to best mitigate its harms and move South Asia towards the green transition? Does the popular understanding of democracy need to be reimagined to include the reproduction of stable and hospitable ecosystems? What would such a change look like and what forces would need to be mobilized to make it?

- How can public officials balance the need for expert input with more deliberative forms of democracy that include citizens in decision-making processes? Could more deliberative systems build greater public trust and increase engagement in civic life?

- Given the dominance in the region of international structures that focus on economic and security matters, such as the Quad and the Belt and Road Initiative, could a democracy-focused regional structure bring greater benefits to its people? How can these structures better incorporate the needs of smaller states while keeping regional powers onboard?

- Does revitalizing civic life and balancing the power of the state and the people require the development of new civic institutions, such as empowered people’s assemblies? Or should governments focus on revamping those already in place?

- How can the region balance leveraging technology for transformative change while avoiding techno-solutionism—the assumption that technology alone can resolve all complex real-world challenges? Can safeguards and oversight mechanisms be put in place to uphold democratic values and protect individual rights?

- Elections are a key countervailing institution and check on the concentration of power, but are increasingly undermined by self-interested elites and disrupted by natural hazards. How can the understanding of elections as critical infrastructure gain greater currency?What forms of multidisciplinary international engagement can be developed to protect elections in a time of climate uncertainty?

Amnesty International, ‘Delay to establishing the board of a fund for people harmed by global warming threatens to undermine human rights’, 21 February 2024, <https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/02/global-delay-to-establishing-the-board-of-a-fund-for-people-harmed-by-global-warming-threatens-to-undermine-human-rights/>, accessed 19 December 2024

Averill, C. and Bhatnagar, J. M., ‘Four things to know about fungi “climate warriors”’, Boston University, 3 August 2018, <https://www.bu.edu/articles/2018/4-things-to-know-about-fungi-climate-warriors/>, accessed 19 December 2024

Averill, C., Dietze, M. C. and Bhatnagar, J. M., ‘Continental‐scale nitrogen pollution is shifting forest mycorrhizal associations and soil carbon stocks’, Global Change Biology, 24/10 (2018), pp. 4544–53, <https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14368>

Beduschi, A. and McAuliffe, M., ‘Artificial intelligence, migration and mobility: Implications for policy and practice’, in M. McAuliffe and A. Triandafyllidou (eds), World Migration Report 2022 (Geneva: International Organization for Migration, 2021), <https://worldmigrationreport.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1691/files/documents/Ch11-key-findings_final.pdf>, accessed 19 December 2024

Chadha, S. S. ‘Negotiating the India-China standoff: 2020–2024’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 11 December 2024, <https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/12/negotiating-the-india-china-standoff-2020-2024?lang=en>, accessed 17 December 2024

Chatterjee, S., ‘The “rurban” society in India: New facets of urbanism and its challenges’, Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 19/8 (2014), pp. 14–18, <https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-19811418>

Dafermos, Y., Gabor, D. and Michell, J., ‘The Wall Street Consensus in pandemic times: What does it mean for climate-aligned development?’, Canadian Journal of Development Studies, 42/1–2 (2021), pp. 238–51, <https://doi.org/10.1080/02255189.2020.1865137>

Economist Intelligence Unit, ‘Global Liveability Index 2024’, <https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/global-liveability-index-2024/>, accessed 19 December 2024

Farrell, M. and Berjon, R., ‘We need to rewild the internet’, Noema, 16 April 2024, <https://www.noemamag.com/we-need-to-rewild-the-internet>, accessed 17 December 2024

Freinacht, H., ‘10 Ways to thoroughly “solarpunk” society’, Metamoderna, 17 July 2022, <https://metamoderna.org/10-ways-to-thoroughly-solarpunk-society/>, accessed 19 December 2024

Gabor, D., ‘The Wall Street Consensus’, Development and Change, 52/3 (2021), pp. 429–59, <https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12645>

Goswami, M., ‘Conceptualizing Peri-Urban-Rural Landscape Change for Sustainable Management, Working Paper 425 (Bangalore: Institute for Social and Economic Change, 2018), <https://ideas.repec.org//p/sch/wpaper/425.html>, 11 December 2024

GOV.UK, Government Office for Science, ‘Features of effective systemic foresight in governments globally’, School of International Futures, 11 May 2021, <https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/features-of-effective-systemic-foresight-in-governments-globally>, accessed 20 December 2024

Hille, P., ‘AI: Chatbots replace journalists’, DW, 21 June 2023, <https://www.dw.com/en/ai-chatbots-replace-journalists-in-news-writing/a-65988172>, accessed 17 December 2024

Hoang, L. A., Lam, T., Yeoh, B. S. A. and Graham, E., ‘Transnational migration, changing care arrangements and left-behind children’s responses in South-East Asia’, Children’s Geographies, 13/3 (2015), pp. 263–77, <https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2015.972653>

Hussain, A., ‘“Climate diplomacy”: Can smog bring India and Pakistan together?’, Al Jazeera, 1 November 2024, <https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/11/1/climate-diplomacy-can-smog-bring-india-and-pakistan-together>, accessed 17 December 2024

Hutchings, H. and Vannucchi, D., ‘Anticipating Futures for Civil Society Operating Space: Mapping the Landscape’, International Civil Society Centre, Solidarity Action Network, October 2022, <https://solidarityaction.network/mapping-anticipating-futures/>, accessed 17 December 2024-

International IDEA, ‘The 2024 Global Elections Super-Cycle’ [n.d.a.], <https://www.idea.int/initiatives/the-2024-global-elections-supercycle>, accessed 17 December 2024

—, ‘Sri Lanka: November 2024’, Democracy Tracker, [n.d.b], <https://www.idea.int/democracytracker/report/sri-lanka/november-2024>, accessed 17 December 2024

—, ‘Bangladesh: August 2024’, Democracy Tracker, [n.d.c], <https://www.idea.int/democracytracker/report/bangladesh/august-2024?pid=7462>, accessed 19 December 2024

—, The Global State of Democracy 2024: Strengthening the Legitimacy of Elections in a Time of Radical Uncertainty (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2024), <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2024.55>

International Organization for Migration (IOM), ‘India presents action plan for Colombo Process chairmanship’, 29 June 2024, <https://www.iom.int/news/india-presents-action-plan-colombo-process-chairmanship>, accessed 19 December 2024

Kenny, E., ‘Sri Lanka’s president and prime minister to resign amidst protests: Democracy in action and challenges ahead’, International IDEA, 13 July 2022, <https://www.idea.int/blog/sri-lankas-president-and-prime-minister-resign-amidst-protests-democracy-action-and-challenges>, accessed 19 December 2024

Keutgen, J., ‘How deliberative processes could save democracy’, Westminster Foundation for Democracy, 25 November 2021, <https://www.wfd.org/commentary/how-deliberative-processes-could-save-democracy>, accessed 19 December 2024

Khan, A. et al., ‘Contribution of mushroom farming to mitigating food scarcity: Current status, challenges and potential future prospects in Pakistan’, Heliyon, 10/23 (2024), e40362, <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e40362>

Kugelman, M., ‘Climate-induced displacement: South Asia’s clear and present danger’, Wilson Center, 30 September 2020, <https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/climate-induced-displacement-south-asias-clear-and-present-danger>, accessed 19 December 2024

Mulmi, A. R., ‘Nepal’s youth are leaving the country in droves’, Observer Research Foundation, 29 January 2024, <https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/nepals-youth-are-leaving-the-country-in-droves>, accessed 17 December 2024

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), ‘Eight Ways to Institutionalise Deliberative Democracy’, OECD Public Governance Policy Paper No. 12, 14 December 2021, <https://doi.org/10.1787/4fcf1da5-en>

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), ‘Human rights risks of using of new technologies in border management need urgent attention, international human rights office ODIHR says’, 20 June 2024, <https://www.osce.org/odihr/570945>, accessed 19 December 2024

Rajendran, L. P. et al., ‘The “peri-urban turn”: A systems thinking approach for a paradigm shift in reconceptualising urban-rural futures in the global south’, Habitat International, 146 (April 2024), <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2024.103041>

Rathore, V. and Mittal, D., ‘Not stubble burning, cars are the main villain in Delhi’s apocalyptic air pollution’, Scroll.In, 21 November 2024, <https://scroll.in/article/1075888/not-stubble-burning-cars-are-the-main-villain-in-delhi-s-apocalyptic-air-pollution>, accessed 17 December 2024

Scott, S., ‘Solarpunk: Refuturing our imagination for an ecological transformation’, One Earth, 27 November 2023, <https://www.oneearth.org/solarpunk/>, accessed 19 December 2024

Shampa, M. et al., ‘A comprehensive review on sustainable coastal zone management in Bangladesh: Present status and the way forward’, Heliyon, 9/8 (2023), e18190, <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e18190>

Sharma, M., ‘Hindu nationalism and right-wing ecology: RSS, Modi and motherland post-2014’, Studies in Indian Politics, 11/1 (2023), pp. 102–17, <https://doi.org/10.1177/23210230231166197>

Shivamurthy, A. G., ‘Why the exodus from Bhutan of young people and qualified workers is a worry for India’, Scroll.In, 18 March 2024, <https://scroll.in/article/1064266/why-the-exodus-from-bhutan-of-young-people-and-qualified-workers-is-a-worry-for-india>, accessed 17 December 2024

Song, C., Wu, Z., Dong, R. K. and Dinçer, H., ‘Greening South Asia: Investing in sustainability and innovation to preserve natural resources and combat environmental pollution’, Resources Policy, 86 (2023), 104239, <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2023.104239>

Surie, M. D., Saluja, S. and Nixon, N., ‘A glass half full: Civic space and contestation in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Nepal’, GovAsia, 2/2 (March 2023), <https://asiafoundation.org/publication/govasia-glass-half-full-civic-space-and-contestation-in-bangladesh-sri-lanka-and-nepal/>

Tsing, A., The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021)

Ullah, I. et al., ‘Projected changes in socioeconomic exposure to heatwaves in South Asia under changing climate’, Earth’s Future, 10/2 (February 2022), <https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EF002240>

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), ‘Indigenous knowledge is crucial in the fight against climate change—here’s why’, UNDP Explainers, 31 July 2024, <https://climatepromise.undp.org/news-and-stories/indigenous-knowledge-crucial-fight-against-climate-change-heres-why>, accessed 19 December 2024

Yeoh, B. S. A. et al., ‘Doing family in “times of migration”: Care temporalities and gender politics in Southeast Asia’, Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 110/6 (2020), pp. 1709–25, <https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2020.1723397>

The archetypes are distinct patterns of change used to develop and explore distinct possibilities for the future and stretch our thinking.

Continuation

Continuation envisages a future without change in respect of current factors, and continuing trends without major disturbances. This future is a continuation of the status quo, where existing patterns and trajectories persist.

Decline

In Decline, the world faces severe challenges that lead to a breakdown in its current structure or functioning. It is important to note that decline does not necessarily mean an apocalypse, but rather a substantial decline in the key systems of the world (e.g. a scenario where the United Nations declines in power due to the rise of BRICS).

Transformation

Transformation is a future where a profound change in society has occurred, in any or all of the technological, spiritual, governance, technological or ideological dimensions. In this scenario, existing factors play out in novel ways that change the world in unexpected ways.

Disciplined Improvement

Disciplined Improvement is a future where the challenges presented by the factors are met by careful management, such as a top-down response or a collective collaboration. The world is not transformed, but a disciplined response leads to a new stabilizing state without the need to overhaul existing values, structures and stakeholders.

Big tech and artificial intelligence

Only a handful of corporations in China and the USA own the majority of social media platforms, as well as digital technologies like generative AI and browsers. Their algorithms and design choices impact people’s access to information and influence political discourse, including elections.

Civic space

A vibrant civic space (including civil society and other informal associations, media, trade unions, etc.) is essential for ensuring political participation and representation. It allows diverse voices to influence decision making and, hold leaders accountable, therefore reflecting popular control.

Climate change and environmental degradation

Climate change is a global problem that can also exacerbate or compound local environmental crises. These have their own unique effects on public health, economic well-being and social stability.

Geopolitics

Global political trends and the foreign policy priorities of major and regional powers can dictate, constrain or undermine policy choices and the ability of democracies to exercise self-determination.

Migration

Migration influences political participation and rights, affecting representation within both host and source countries and shaping democratic norms related to inclusion and political equality. Migration pressures often include political, economic, social, climate, identity and security-related motivations.

Continuation

Milan Rai is a Khambu (Indigenous) artist, born in his ancestral land, Khambuwan, now known as eastern Nepal. Milan works with installation, intervention, performance and film. Recurring themes in his work include the changing climate, the nature–culture dichotomy and Indigenous futurism. He reimagines progress, shifting Indigenous agencies from victims of climate change narratives to navigators of different futures. Milan perceives his work as a creative continuum—interwoven, multifaceted and multidimensional. In the rest of this annex, in his words, Milan talks about his photographs used in this report.

In 2012, I conceived ‘White Butterflies’ to weave art into everyday context, away from the commodification of art and elitism. Institutionally funded public art can limit engagement through curated placement and context, and may not be inherently democratic. I spread swarms of paper butterflies throughout public spaces. Passers-by paused at this ephemeral installation, experiencing unexpected moments of connection and wonder. Through technological webs, the butterflies’ energy fluttered across social media, connecting global communities and their stories. These delicate paper butterflies embodied my quest in the creative process and effort to re-enchant the world around me. Hearing that thousands of trees would be felled for road expansion, I placed white butterflies on these trees as art—resistance to forced urban expansion.

My intervention stems not from disenchantment with the system, but from a desire to re-enchant these spaces. Witnessing butterflies emerge in the green spaces I reclaimed evokes memories of the metaphorical butterflies I placed in public spaces. This feels like a creative continuum. This idea of continuity contrasts with the recurring mistakes and the continued progression of development. Who decides what is worth continuing, and on whose terms? My ongoing work deepens this inquiry into why such continuation persists.’

Discipline

In 2017, I stood in Kathmandu’s polluted streets, wearing a gas mask—my body an extension of the landscape. I entered city offices demanding accountability. In holding the system accountable, I also held myself responsible for my actions and toward the community. Discipline is internalized, not imposed. When do our intrinsic roles and responsibilities get overridden by colonial conceptions of governance? The autonomy of Indigenous communities was overtaken by these forces. I, too, was confined by a school system that equated discipline with obedience and control. I dropped out, finding freedom in art and the inner strength to overcome the fear they instilled. I seek what it means to be disciplined, responsible, and free through my creative journey.

For 21 months, I wore a gas mask while circling city offices. It is my longest performance piece, that defies the conventional boundaries of art spaces. I asserted my presence in bureaucratic corridors, interweaving self-discipline with political commentary in a dialogue with authorities. My engagement with officials was deemed futile as forces sought to undermine my efforts. Yet, I embraced this struggle as a practice—a discipline lived through art. I deepened my resolve, compounding momentum and forging connections that informed me about park projects from the mayor’s office. I reviewed their designs and urged the mayor of Lalitpur to rethink the execution of these plans. I proposed a shift from exploitation to a reciprocal relationship with the land. These are not romanticized parks; they are spaces for healing, connection, and transformation.

I envision parks through the lens of ecological democracy, inviting communities and the land into participatory futures. How can governance evolve to heed the voice of the land? Indigenous knowledge systems can be the foundation for this reimagined democracy and ecological sovereignty. Recognizing humans and non-humans within a web of relationships, it asks: Whose vision shapes public space, and how are communities systematically overlooked? When the system was reluctant to change, I rejected institutional approval and strived to reclaim public spaces. While they prioritized park designs and construction, I dedicated myself to UN-DESIGNING and UN-MAKING, refusing norms and institutional expectations.

Collapse

The unsustainable systems of modernity cannot be salvaged by the same destructive mechanisms. As this system crumbles, we must accept that collapse is not only inevitable but necessary for regeneration. Here, we acknowledge the damage, mourn, and let it pass, with this transition being not violent, but compassionate. Rather than convinced by apocalyptic visions that inflict fear and trauma—I place my hope in healing—envisioning a different future.

Transformation

My urban intervention engages with the transformative potential of de-construction. The convenient narrative of growth oversimplifies the complexities of transformation. Fragmenting the land and fabricating park projects as transformation disguises the ongoing struggles and unresolved tensions. How do different cultures, more-than-human worlds, and ecosystems experience transformation? What are the gains and losses? What are the ethical, emotional, and ecological consequences? Words like transformation and impact spill over development reports. While essential, their overuse, without deeper engagement, undermines their meaning.

My intervention was depicted with ‘before and after’ images in a report by international non-governmental organizations and local government, marking a project with time-bound dates. I see it differently—as a 1,000-year initiative, where transformation transcends singular events. I do not view my urban interventions as a final outcome. Transformation, in my experience, is not a destination but a liminal space.

| Name | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Niranjan Sahoo | Observer Research Foundation |

| Md. Abdul Alim | Democracy International |

| Siok Sian Pek-Dorji | Druk Journal |

| Tashi Pem | Helvetas |

| Bidhayak Das | Independent consultant |

| Namrata Raju | Labour rights and migration consultant |

| Mariyam Zulfa | Maldives Policy Advocacy Caucus |

| Kunda Dixit | Nepali Times |

| Maheen Pracha | Human Rights Commission of Pakistan |

| Zuha Noor | Pakistan Institute for Human Rights |

| Daniel Riveong | Plural Futures |

| Ammaarah Nilafdeen | School of International Futures |

| Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu | Centre for Policy Alternatives |

| Hasini Haputhanthri | International Centre for Ethnic Studies |

| Iromi Perera | Colombo Urban Lab – Centre for a Smart Future |

| Mark Salter | Independent consultant |

| Asoka Obeyesekere | National Democratic Institute |

| Durga Karki | International IDEA |

| Leena Rikkilä Tamang | International IDEA |

| Michael Runey | International IDEA |

| Emma Kenny | International IDEA |

| Atsuko Hirakawa | International IDEA |

- The citations throughout this report are not necessarily the inspiration or the specific grounds for a certain claim. These were the product of the in-person, interactive and communal discussions that took place in the South Asia Outlook Forum. That is not to say that these forums are not deeply rooted in factual expertise; only that the sources are intended as a resource for increasing understanding of the context for a given statement or a recommendation for further reading.

- A complete list of factors as they were formulated at the forum can be found in Annex B.

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

|---|---|

| ASEAN | Association of Southeast Asian Nations |

| GSoD | Global State of Democracy |

| SAARC | South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation |

This discussion paper was developed as a follow-up to the Democracy in South Asia Outlook Forum held in Colombo, Sri Lanka, in November 2024. The forum was jointly organized by International IDEA and the Centre for Policy Alternatives.

The paper was authored by Michael Runey and Emma Kenny and was reviewed by Leena Rikkilä Tamang, Seema Shah, Atsuko Hirakawa, Daniel Riveong, Michele Poletto, and Elin Westerling. It is based on the invaluable work and insights of the forum participants (see Annex D for a list of participants). We thank our colleagues at International IDEA’s Asia and the Pacific regional office and their network of partners whose conversations helped with the conceptualization of this paper.

© 2025 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members.

With the exception of any third-party images and photos, the electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0>.

Design and layout: International IDEA

DOI: <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2025.1>

ISBN: 978-91-7671-873-5 (PDF)

ISBN: 978-91-7671-880-3 (HTML)