Democracy Tracker Methodology and User Guide

Version 2, February 2025

The Democracy Tracker is a data project that provides event-centric information on democracy developments in 173 countries, with a data series beginning in August 2022. The monthly event reports include (a) a narrative summary of the event; (b) indications of the specific aspects of democracy that have been impacted; (c) the magnitude of the impact on a five-point scale ranging from exceptionally positive to exceptionally negative; (d) links to original sources; and (e) keywords to enable further research. The project is run by the Democracy Assessment (DA) Unit at International IDEA. To produce the reports, analysts in the DA Unit review thousands of documents every month, including media reports and varied expert analysis and advocacy and, where needed, directly contact in-country experts.

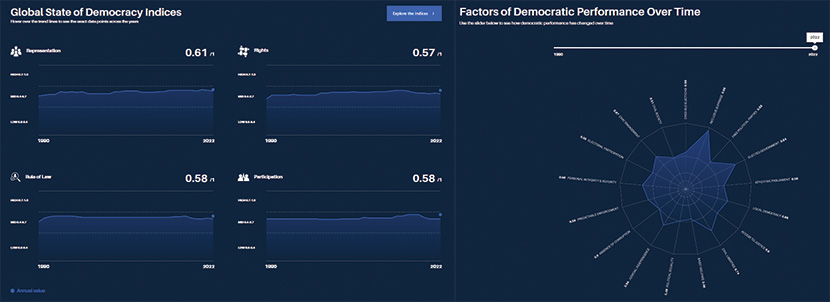

The Democracy Tracker is grounded in the Global State of Democracy (GSoD) conceptual framework and thus covers 29 aspects of democratic performance, which are organized hierarchically into ‘categories’, ‘factors’ and ‘subfactors’. Among its many uses, the Democracy Tracker acts as a qualitative and timely complement to the annually updated quantitative scores found in the Global State of Democracy Indices (GSoD Indices).

The Democracy Tracker reports events that signal a significant change in a country’s democratic performance in a particular month, either positively or negatively. In addition, it reports events that signal such a change is very likely in the near future (events to watch) and all national elections. The reporting is not intended to be a comprehensive accounting of political events but is intended to focus attention on events that have an impact on the quality of democracy in a given country. Evaluations of the direction and magnitude of the events’ effects are relevant to a specific month and reflect each country’s particular context. They are therefore not comparable between countries and across time.

While the Democracy Tracker’s primary audiences are policymakers and influencers—including donors, development cooperation actors and advisors to, and the staff of, government ministers and legislators—it is also useful for the media, researchers, civil society and anyone else who wishes to stay informed. The data can be useful for a range of outputs, including diplomatic briefings, policy briefs, media reports, academic articles, strategic planning and risk assessment.

Ultimately, the Democracy Tracker reports are launching pads for deeper analysis.

The Democracy Tracker aims to:

- provide regular, qualitative information that can ‘round out’ the meaning of the quantitative scores provided by the annually updated quantitative data in the GSoD Indices; and

- go beyond the indicators in the quantitative data set and thus provide a more holistic picture of contemporary democratic developments.

2.1. Units of analysis

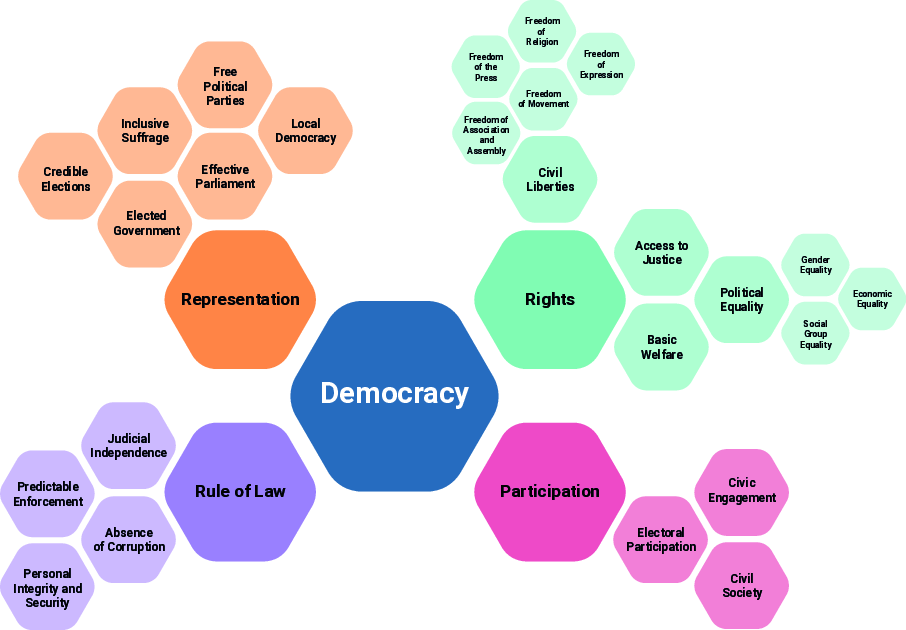

The Democracy Tracker reports at monthly intervals at the country level. Generally, therefore, the unit of measurement is the country-month. However, each country-month may include any number of event report observations. Whenever at least one event report has been created, there will also be an overall country-month observation. As described in further detail below, the magnitude of the impacts of the events is coded on a scale from ‘exceptionally negative’ to ‘exceptionally positive’ and with reference to the conceptual framework developed for the GSoD Indices. The organization of these concepts is shown in Figure 2.1. A list of covered countries is included in Annex A.

The choice to use states as the unit of analysis creates some challenges, but it is the unit that can be used most consistently. Even so, some events have a transnational character. Good examples of this include interstate (and sometimes intrastate) wars, environmental catastrophes and migration. When reporting on events that have a transnational aspect, the Democracy Tracker seeks to maintain the state-centric approach by reporting the event in the country or countries in which the event took place, even if the event was caused somewhere else. For example, if the rights of migrants are violated in a particular country, the event is reported there, even if the violation occurred as a result of policies created elsewhere. The state-centric methodology also means that the Democracy Tracker only reports on the activities of supranational institutions (such as the United Nations, European Union and African Union) when those activities have a direct impact on the state of democracy in a particular country. There are times when investigative reports reveal long-standing and systematic problems that may not have been common knowledge. In these cases, analysts determine how the revelations impact the status quo in a country and then integrate a description of the findings into the country profile narrative. In this way, the findings are considered a part of the country’s context rather than a ‘new event’. New developments related to the investigations’ findings are then subsequently reported as standard event reports, as relevant.

Similarly, while the use of months as the unit of time has some disadvantages, it appears to be a unit that is both useful and manageable. Monthly event reports are published by the middle of each month and reflect the previous month’s developments. In general, monthly event reports will strictly reflect what happened in one month only. When relevant, however, some flexibility can be applied in order to avoid creating artificial limitations in reporting that would hinder users as they look for information in the Democracy Tracker. Finally, there are exceptional cases when significant developments are identified and assessed as meeting the threshold of reporting several months after the actual event has taken place. In such cases, an event report is added retroactively as a standard or a ‘to watch’ report in the month the event took place.

2.2. Concepts

Many aspects of the Democracy Tracker’s methodology are anchored by International IDEA’s conceptual framework of democracy, originally created for a qualitative assessment process (the State of Democracy Assessments) and in its most recent iteration formulated for the GSoD Indices.

The framework is hierarchical and is based on four core categories of democratic attributes—Representation, Rights, Participation and the Rule of Law. The four categories are made up of factors (such as Credible Elections or Judicial Independence). Finally, at the lowest level are subfactors (such as Freedom of Expression or Social Group Equality). Please refer to the GSoD Indices methodology and codebook for more detailed information on the GSoD conceptual framework.

3.1. Standard event reports

Most of the event reports in the Democracy Tracker take the form of a standardized summary of what analysts consider to be the most important democracy-related developments every month. These reports include a narrative describing the event, its context and its significance. Analysts are asked to do this as concisely as possible, ideally using between 500 and 1,000 characters to convey only the necessary information. Data users can access linked sources for further details as necessary. Analysts also provide an assessment of the direction and magnitude of each event using the five-point scale (see 4.3.2: Coding event impacts). These narratives are drafted by the analysts and edited and fact-checked by the staff tasked with quality control (see below).

3.2. ‘To watch’ reports

In some cases, recent events have not reached the level of significant change required for a standard report, but there is good reason to believe that an ongoing process will reach that threshold within a year. These events may be reported as ‘to watch’ (see 4.2: Inclusion rules for further details on the reporting of this type of event). Because the anticipated impacts have not yet materialized, such events are reported with neutral coding (which differs from the standard event reports).

3.3. Election reports

Elections are at the core of contemporary democratic practice and as such are always reported in the Democracy Tracker. Neutral event reports are therefore written for every national election. They contain straightforward, non-judgemental descriptions of the official results and other key data (for the guidance on the content of the election report, see 4.2.4: National elections). The neutrality of the election reports means that they do not include coding of the direction or magnitude of any impact of the election on the quality of democracy in the country.

4.1. Data collection

The data collection process involves a comprehensive review of online and print news media items and expert reports and analysis relating to democracy in each of the 173 countries at monthly intervals. Analysts primarily use two large-scale media monitoring services that collect media and expert reporting from around the world, supplemented by country-specific data sources and individual expert inputs where needed.

The first media monitoring source is Nexis NewsdeskTM, produced by the publisher LexisNexis. Nexis Newsdesk allows access to reporting from more than 100,000 media outlets, covering 235 countries and regions, and includes content in more than 100 languages. In collaboration with the content experts at LexisNexis, analysts have created a number of complex Boolean queries that identify the media reports that are relevant to the aspects of democratic performance that are covered by the Democracy Tracker. The search results are often filtered and denoised using Nexis Newsdesk’s tools, which leverage the known characteristics of media sources to identify the most useful and authoritative reporting. These tools are used differently depending on the volume of media and expert coverage in each country (i.e. more filters are required in larger countries with more media outlets). Nexis Newsdesk includes both free and licensed content, including subscriptions to the main print sources in many countries. Analysts make frequent use of in-browser translations to read content published in languages that they do not read.

The second media monitoring source is the Global Database of Events, Language and Tone (GDELT), which covers online media in 65 languages. GDELT scrapes many thousands of news sites for content, and is updated at

Finally, as necessary, analysts also consult major news sources in the countries to which they are assigned as a final step to ensure that nothing has been missed. In each region, there are some relatively authoritative news sources and analysts give special attention to events reported in these news outlets.

Beyond news media, analysts utilize information reported by national and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and UN agencies. Wherever possible, analysts also consult primary sources, including court judgments, legislation, election observation reports and official government communications. In cases where information is difficult to find, the publicly available information is not consistent or the event is controversial or sensitive, or if analysts assess that on-the-ground verification/supplemental information is necessary, analysts consult with International IDEA’s regionally based experts and country offices, and other local experts and partners.

Analysts will not include events that have only been reported in low-quality media sources, or which are not reported by multiple independent media and expert sources. However, events reported by only one media source can be included if the source has a reputation for quality of international standing or if the story can be verified by International IDEA’s regional and country-based staff or by International IDEA’s partners. For example, if a major national newspaper or an international wire service published exclusive reporting on a significant event, this can be included even if other media organizations cannot confirm the report. Whenever possible, analysts will include at least one local source in addition to international sources.

4.2. Inclusion rules

Having used news media and expert data sources to comprehensively assess what has taken place in a given country, in a given month analysts must then decide which events should be reported in the Democracy Tracker. As noted above, events are selected for reporting on the basis that they signal a significant change in the status quo, either positive or negative. In addition to these, the Democracy Tracker also reports events that signal such a change is very likely in the near future (events ‘to watch’) and all national elections.

The Democracy Tracker is not intended to be a comprehensive accounting of political events. Instead, the value added is in classifying events and describing their impact on the quality of specific aspects of democracy. This means that many events that have political significance are not reported, because they are a continuation of the status quo. Many final decisions about what to include are made at the quality control stage, as more senior staff are consulted about what may constitute a notable change in the status quo.

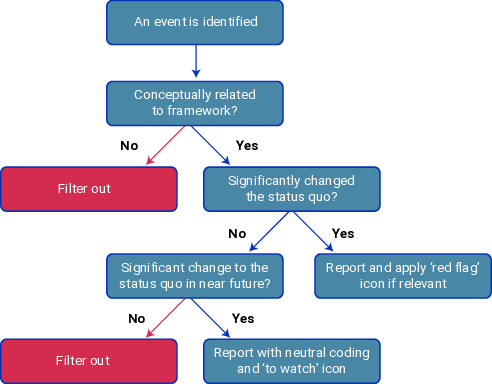

As noted above, all national elections are reported in the Democracy Tracker. For all other events, analysts use the following questions to decide whether or not an event should be reported (see also an illustration of the decision-making process in Figure 4.1):

- Is the event closely related to a concept in the GSoD conceptual framework?

- If yes, the analyst moves on to the next question.

- If no, the event is filtered out.

- Has the impact of the event changed the status quo in the country to such an extent that it will very likely prompt a change in the current GSoD Indices score(s)?

- If yes, the analyst reports the event and codes the direction and magnitude of the impact of the event for the relevant concepts (and may add a ‘red flag’ icon where relevant—see 4.3: Coding procedure for details of coding and icons).

- If no, the analyst moves on to the next question.

- Is the event notable in and of itself and is it very likely to have a significant impact on the status quo in the country in the next 12 months?

- If yes, the analyst reports the event with neutral impacts and applies the ‘to watch’ icon.

- If no, the event is not reported.

4.2.1. Conceptually related to the GSoD framework

To ensure alignment between the GSoD Indices and the Democracy Tracker, events are only reported when they bear a close conceptual relationship to one or more of the categories, factors or subfactors in the GSoD Indices conceptual framework (see Figure 2.1). To help them define the parameters of the framework, analysts may consult the GSoD Indices methodology (which defines the concepts); however, a broader understanding of the concepts is often appropriate for the qualitative assessments made in the Democracy Tracker.

Examples of types of issues that are not directly measured by the GSoD Indices but are still sufficiently related to the core concept include (a) those that focus on suffrage (the GSoD Indices include only de jure measures of suffrage, while the Democracy Tracker includes de facto disenfranchisement and special voting arrangements); (b) gender-based violence (GBV) (the GSoD Indices do not include GBV as part of Gender Equality but the Democracy Tracker does include GBV stories when they have significant impacts at the country level); and (c) digitalization (the GSoD Indices cover digital aspects of the freedom of information, but the Democracy Tracker reports broader digitalization and democracy issues). The Democracy Tracker also includes (d) events that focus on non-citizens (e.g. migrants, refugees and asylum seekers). These events are reported in the country in which the event takes place (i.e. a story on the capsizing of a migrant boat off the coast of Italy would be coded in Italy if the Italian authorities had the responsibility to respond).

Please see the concept descriptions in Annex E for a comprehensive description of what is included in each factor.

Decision-making examples

Egypt, August 2023

As of August, the Egyptian Government has been implementing daily power cutbacks to manage a nationwide energy crisis. However, these measures have been disproportionately affecting the poorest areas in the country, where access to electricity is now severely limited. This has significant implications for economic and social rights, as it disrupts essential services such as lighting, refrigeration and electronic communication. The situation has been exacerbated by a severe heatwave since mid-July, with the resulting frequent and lengthy power outages making conditions even more challenging for Egyptians. The energy crisis is also impacting Egypt’s tourism industry, with many establishments turning to fuel generators due to constant power interruptions. These ongoing issues represent a significant socio-economic challenge for the country, symbolizing wider problems under President Sisi’s administration. Experts warn that the sustained crisis could potentially disrupt essential services, including hospitals and medical centres.

Proposed categories: Rights

Proposed factors: Basic Welfare, Political Equality

Proposed subfactors: Social Group Equality

Decision: NOT REPORTED. Insufficiently strong connection to the category, factors and subfactor proposed.

Taiwan, August 2023

Taiwan’s legislature swiftly responded to the country’s latest #MeToo movement and recent high-profile cases triggered by the hit show, Wave Makers, amending three key laws on sexual harassment. On 31 July, amendments to the Gender Equity Education Act, Act of Gender Equality in Employment and Sexual Harassment Prevention Act were passed. These changes introduce harsher penalties, including up to three-year jail terms and substantial fines, along with longer statute of limitations and broader definitions of sexual harassment. The ruling party also took prompt action to remove officials implicated in sexual misconduct cases. However, critics argue that these amendments, while a ‘legislative milestone’, fall short in addressing harassment beyond the workplace. Activists call for increased fines to prevent retaliation and more targeted educational initiatives to challenge societal attitudes towards sexual harassment.

Categories: Rights

Factors: Political Equality

Subfactors: Gender Equality

Decision: REPORTED. The event concerned sexual harassment, a form of GBV. GBV is only partially measured by the GSoD Indices but it is a fundamental aspect of gender equality and so the necessary conceptual relationship between the event and the framework was judged to exist.

4.2.2. Status quo changed

The principal category of events reported by the Democracy Tracker are those which have significantly changed the quality of the country’s democratic performance. The following non-exhaustive list of questions helps to guide this assessment:

- Is this event part of an observed pattern for at least the last three months?

- Is this event part of a broader phenomenon or pattern and does it add another dimension to that phenomenon or clearly entrench that phenomenon?

- Is the impact of the event likely to be long-lasting?

- If the scale of the event can be quantified (e.g. number of protesters/casualties/women elected), how does it compare with prior events of this sort?

- Has the event brought about structural change (e.g. enactment of a law or a precedent-setting court judgment)?

Decision-making examples

Sweden, June 2023

Parliament approved amendments to the criminal code to strengthen the protection of journalists and prevent attacks on reporters. The changes aim to safeguard impartial reporting by journalists by minimizing the risk of exposure to threats which may affect their work or lead to self-censorship. The amendments ensure that crimes committed against a person because of their role as a journalist are assessed more harshly and carry higher penalties. Recent research by Lund University found a need for increased resources and priority within the legal system to address online harassment against journalists. The changes also introduce penal provisions to expressly prevent abuse and harassment against other ‘socially beneficial functions’, including personnel in healthcare, social services, rescue services and schools, to ensure the uninhibited performance of duties deemed critical for society and to protect occupations that are especially exposed to threats.

Decision: REPORTED. The new legislation brought about structural change in terms of the protection of journalists in Sweden and therefore constituted a significant change in the status quo with regard to Freedom of the Press.

Madagascar, August 2023

On 10 August, chief of staff to President Andry Rajoelina, Romy Voos Andrianarisoa, and a French associate (Philippe Tabuteau) were arrested in London on suspicion of soliciting a bribe from the mining firm Gemfields. The United Kingdom’s National Crime Agency (NCA) alleges that Ms Andrianarisoa and Mr Tabuteau asked Gemfields to give them GBP 225,000 and a 5 per cent stake in any Gemfields projects in Madagascar in exchange for mining licences. The NCA made no allegation against President Rajoelina, who is running for re-election in November. Ms Andrianarisoa pled not guilty on 9 September and will face trial in early 2024.

Decision: NOT REPORTED. The charges had not been proven in court and there was no apparent connection with the President.

4.2.3. Future changes in the status quo (events ‘to watch’)

The Democracy Tracker also reports events that are notable in and of themselves and that are very likely to have an impact on the status quo in the country in the near future (i.e. within the next 12 months—this must be clearly communicated in the narrative of the report). Analysts only report this type of event when they are confident that the predicted impact will materialize in the near future. This is most often the case where the event is procedural, with a trajectory and impact that is reasonably foreseeable. An example would be the introduction or passage of a bill, the potential impact of which is indicated by its provisions and the path to enactment is governed by domestic rules. Bills awaiting executive or royal assent will be reported as ‘to watch’ when their likelihood of entering into force is uncertain or not imminent. Non-procedural events, such as state repression of protesters, or procedural events whose outcomes are generally less predictable (such as the arrest of senior opposition party leaders) are reported where the context allows the analyst to say with confidence that the event is likely to have an important impact on democracy and where their assessment is supported by the opinion of one or more country experts. A ‘to watch’ report includes descriptive text clarifying (a) how the event connects to the GSoD conceptual framework and (b) which future developments to monitor in order for the predicted impact on the status quo to materialize. ‘To watch’ reports should only be used if such future developments are not imminent. If the analyst expects such future developments to occur within a highly condensed timeframe (e.g. one month), the event can be captured in a standard report the following month.

Generally, when there are new developments related to the ongoing process which are expected to impact the status quo, the ‘to watch’ report is ‘closed’ through a new, standard report that conveys the end or closure of the process. See 4.4.1: Updates below for more details.

Every month, analysts from each region will select one ‘critical event to watch’, which will be featured on the Democracy Tracker homepage.

Decision-making examples

Uganda, March 2023

On 21 March, Ugandan parliamentarians voted almost unanimously (389 to 2) to pass the Anti-Homosexuality Bill 2023, a piece of legislation which, if signed into law, would further restrict the human rights of LGBTQIA+ people in the country. While the rights of this community are already severely constrained under Ugandan law (e.g. same-sex sexual relations are illegal and LGBTQIA+ rights groups are prevented from registering with the state), the Bill would expand these restrictions in important respects. It would, for example, criminalize identifying as an LGBTQIA+ person and ‘promoting homosexuality’, which would likely include advocating for LGBTQIA+ rights and financially supporting such advocacy and so could have significant implications for civil society engagement. These crimes would be punishable with lengthy prison sentences. The version of the Bill amended on 21 March (yet to be published) also includes the death penalty for the crime of ‘aggravated homosexuality’ (where same-sex relations are carried out in one of a select list of ‘aggravating’ circumstances, e.g. where the offender is a serial offender or the victim is under 18). President Yoweri Museveni has 30 days to assent or reject the legislation.

Decision: REPORTED. The Anti-Homosexuality Bill had been passed by the legislature but not yet signed into law. However, its strong support among legislators and supportive comments from President Museveni had indicated that it would be signed into law within six months. Expert legal analysis of the Bill stated that, if enacted, it would significantly change the status quo with regard to LGBTQIA+ rights.

Senegal, March 2023

In the lead up to the 2024 presidential election, Ousmane Sonko has emerged as a likely candidate to challenge President Macky Sall (who is widely expected to seek a third term). Sonko’s potential candidacy is impaired by two criminal trials: one involving charges of rape and death threats, and another involving an accusation of libel against a government minister. As the date of the first trial approached at the end of March, his supporters clashed with police in a number of locations across the country. Adding to the tensions, Sonko made accusations of an assassination attempt after he was exposed to a chemical irritant as he was physically forced into the court building. Sonko’s first trial ended on 30 March. He was found guilty of libel but given a two-month suspended sentence that will not prevent his candidacy. The rape trial is yet to begin but can be expected to generate unrest when it does.

Decision: REPORTED. The event was very likely to prompt a significant escalation in anti-government protest and state harassment of government opponents in the near future.

Romania, October 2023

An open letter was addressed to the Romanian Parliament by 56 NGOs and academics, calling for the introduction of legislated gender quotas in parliamentary elections. Romanian law requires all political parties to ensure that men and women are represented on electoral lists, without specifying any minimum representation levels. A bill, pending in Parliament since 2022, would require candidate lists for parliamentary elections to the Chamber of the Deputies and the Senate to be composed of at least 33 per cent women. The window for electoral reform before the November 2024 elections is closing, where amendments can be made up to one year before elections. The letter, initiated by women’s rights NGO FILIA Center, calls for the introduction of zipper measures, to ensure women candidates have access to eligible positions rather than being relegated to the bottom of the electoral lists. In the 2016 and 2020 elections, women made up around 30 per cent of candidates. The current Chamber of the Deputies, the lower house of Parliament, is comprised of 19 per cent female lawmakers.

Decision: NOT REPORTED. The event was not critical or mature enough to be reported. This could be reported, however, if and when more specific steps are taken in the future (e.g. if the legislation progresses further).

4.2.4. National elections

The critical importance of elections to democratic governance means that the Democracy Tracker reports all national elections. Election reports contain non-judgemental descriptions of the official results and other key data (for guidance on the content of the election report, see the list of information to cover below). The neutrality of the election reports means that the impacts of the event are not coded. However, it is important to note that, where the analyst determines that an aspect of the election marks a significant change in the status quo—for example in the level of repression, the number of women elected or other matters of substantive importance—they will report this in a separate, conventional event report in which the magnitude of the impacts is recorded with the usual directional coding. In general, election reports do not include the ideological positions of political parties, though there may be exceptional circumstances, for example to elucidate a change in political power dynamics or underscore the party’s significance given the country’s context and history.

Election reports constitute neutral descriptions of the official results and will cover (subject to the availability of information close to the election):

- the date(s) on which voting took place;

- which offices were contested in the election;

- the official election results, including vote share to one decimal place (note: in the case of legislative elections, election results are conveyed in terms of seats won by leading candidates and political parties; vote share is optional);

- any legal challenges to the results;

- key findings of election observers (where available);

- voter turnout to one decimal place; and

- number of women elected and number of women candidates.

Election report example

Maldives, September 2023

Mohammed Muizzu, the opposition candidate from the Progressive Alliance (a coalition of the Progressive Party of Maldives and People’s National Congress), won the presidential run-off on 30 September with 54 per cent of the vote, defeating Ibrahim Solih of the Maldivian Democratic Party. The run-off followed the 9 September election, where no candidate secured the minimum 50 per cent of required votes. Voter turnout increased from 79.98 per cent on 9 September to 87.31 per cent on 30 September. A record eight candidates ran in the election, with no female candidates. Transparency Maldives reported overall peaceful elections despite isolated incidents of violence.

4.3. Coding procedure

4.3.1. Areas of impact

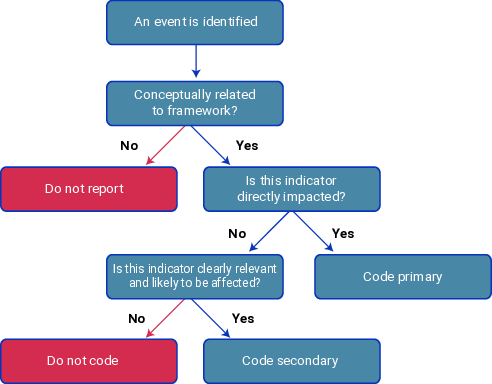

If an event merits inclusion, the next step is to code the direction and magnitude of the impact of the event with reference to the relevant categories, factors and subfactors of democratic performance. These indicators are coded at two levels—primary and secondary. This shows which aspects of democracy are principally impacted by the event and which aspects are secondarily impacted. Coding takes place first at the lowest level of analysis (i.e. the factor or subfactor). Coding the direction and magnitude of the impact of an event at the factor level then necessitates coding the category as well (see below for further details). The following guidelines are used to make the distinction between primary- and secondary-level coding:

- If an indicator is principally impacted by an event (i.e. it is directly and significantly impacted), it will be coded as primary.

- If a factor is secondarily impacted by an event (i.e. it is relevant but not directly impacted), it will be coded as secondary. The effects of the event on the secondary factor will be coded as neutral (zero on the five-point scale).

This decision-making process is also illustrated in Figure 4.2.

Coding examples

Azerbaijan, August 2023

Former Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court Luis Moreno Ocampo published a report arguing the ongoing Azerbaijani blockade of the disputed majority Armenian territory of Nagorno-Karabakh should be considered genocide on 7 August. On 15 August, the Nagorno Karabakh Human Rights Defender’s Office said a man had starved to death, marking the first death as a result of the months-long blockade which has prevented food, medicine, fuel and electricity from reaching the region. A UN Security Council meeting on the crisis on 16 August failed to result in a statement, as Azerbaijan’s close ally and non-permanent member Türkiye disputed Armenia’s claims and defended Azerbaijan’s justification to blockade the region.

RED FLAG

Primary categories: Rule of Law

Primary factors: Personal Integrity and Security

Primary subfactors: N/A

Secondary categories: Rights

Secondary factors: Civil Liberties, Political Equality, Basic Welfare

Secondary subfactors: Freedom of Movement, Social Group Equality

Guatemala, July 2023

Concern over the integrity of Guatemala’s presidential race arose after the Constitutional Court suspended the certification of the first-round electoral results pending the review of ballots, after rival parties complained about alleged inconsistencies in votes. The measure was widely criticized as unwarranted. After the delay in announcing official results, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal confirmed that Bernardo Arevalo and Sandra Torres would face each other in a run-off. In the weeks after the first-round, upon the request of a special anti-graft prosecutor, a lower court granted the suspension of Arevalo’s Semilla party. Also at the request of the anti-graft prosecutor, warrants were granted to carry out a raid on Semilla party’s headquarters as part of an investigation into the authenticity of signatures during the process of the party’s registration, last year. Prosecutors also carried out searches of the Supreme Electoral Tribunal, actions denounced by the UN, EU and Guatemalan protesters, particularly due to the legal framework that prohibits the suspension of a political party while an electoral process is underway. The Constitutional Court blocked the suspension of Semilla party so the run-off can go ahead.

Primary categories: Rule of Law

Primary factors: Predictable Enforcement

Primary subfactors: N/A

Secondary categories: Representation

Secondary factors: Credible Elections, Free Political Parties

Secondary subfactors: N/A

Ecuador, May 2023

President Lasso has issued an executive decree that authorizes the armed forces to participate in operations against cartels, in coordination with national police, to address the ‘terrorist threat’ that organized crime poses. The decree follows a resolution by the country’s security council, in which it found that gangs use terrorist tactics and recommended that the executive address such threats through armed action. Analysts and human rights experts fear that the measure will lead to abuses and a disproportionate use of force.

Primary categories: Rights, Rule of Law

Primary factors: Civil Liberties, Personal Integrity and Security

Primary subfactors: Freedom of Movement

Secondary categories: N/A

Secondary factors: N/A

Secondary subfactors: N/A

4.3.2. Coding event impacts

Having determined which factors have been impacted, the next step is to code the magnitude of the impact. Each standard event report in the Democracy Tracker is coded on a five-point scale (ranging from ‘exceptionally positive’ to ‘exceptionally negative’) indicating the magnitude and direction of an event’s impact on relevant categories and factors of democracy (as defined by the GSoD Indices, see Figure 2.1). ‘To watch’ events always take on a neutral coding. As noted above, for each event, directional coding takes place at the lowest level of the theoretical framework (either the factor or subfactor level depending on the factor) and then at the category level. While rare, it is possible to code an event as having different directional impacts on the various relevant factors even within a single category. As the coding takes place primarily at the event level, this poses no immediate procedural problems. However, with upwards aggregation more rules must be applied.

Scale

| Code | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Exceptionally positive | The event signals an exceptionally positive change in the status quo |

| Positive | The event signals a significant positive change in the status quo |

| Neutral | The event is neutral and does not impact on the status quo |

| Negative | The event signals a significant negative change in the status quo |

| Exceptionally negative | The event signals an exceptionally negative change in the status quo |

Application of the scale

Having determined at the inclusion stage that the event represents a significant deviation from the status quo, the analyst has determined that the event merits inclusion. In assessing whether the magnitude of the event’s impact has been exceptionally positive or negative, analysts are guided by the following questions.

Exceptionally positive:

- Does this event reflect the codification of new rights or laws that protect democratic institutions and/or norms?

- Does this event reflect a significant change in the context such that there are markedly more openings for democratic reform?

- Is this event representative of the significant expansion of any individual factor or category, such that it will be difficult to describe the context without referencing this development?

Exceptionally negative:

- Is this event a coup d’état, unconstitutional change of regime, political assassination or an outbreak of severe armed hostility?

- Does this event include the pronouncement of genocide, crimes against humanity or other severe violations of international law?

- Is this event representative of the severe degradation of any individual factor or category, such that it will be difficult to describe the context without referencing this development?

Coding examples

Russia, April 2023

Several bills signed into law on 28 April raised the maximum sentence for treason to life in prison and allowed for depriving naturalized citizens of their citizenship for ‘discrediting’ the armed forces. A decree signed by President Vladimir Putin on 27 April legalized the deportation of residents of illegally occupied Ukrainian territory who decline to take up Russian citizenship. The laws and decree are interpreted as providing the Russian state with more tools to punish and discourage dissent.

Event-level coding:

Primary categories: Rights (exceptionally negative)

Primary factors: Civil Liberties (exceptionally negative)

Primary subfactors: Freedom of Expression (exceptionally negative), Freedom of Movement (exceptionally negative)

Secondary categories, factors and subfactors: N/A

Ecuador, August 2023

In a referendum held on 20 August, over 58 per cent of voters chose to stop oil extraction in the Yasuni National Park, a UN protected biosphere located in the Amazon. In a second referendum, Ecuadorians also voted to ban all extraction activities in the Choco Andino tropical rainforest, near Quito, with around 68 per cent support.

Efforts to contain oil production in the Amazon had been spearheaded by Indigenous Peoples and environmental activists, many of them young people, for years. Officials across several administrations and the state’s oil company, Petroecuador, had argued that an end to oil development in Yasuni would lead to austerity measures with a negative impact on the economy. Petroecuador will have to dismantle its oil processing facilities and provide for reparations.

According to Human Rights Watch, the vote on the Yasuni is the first time a referendum has resulted in a ban on new and pre-existing fossil fuel exploration. Turnout for this referendum neared 83 per cent. Notably, the decision will benefit the Taromenane, Tagaeri and Dugakaeri peoples, who choose to live in isolation in the region, as the drilling activities impacted the quality of their water and resources. Environmental activists have organized to demand the government’s compliance with the referendum as, following the results, officials, including incumbent president Lasso, as well as the candidate currently leading in polls to succeed him, have expressed reservations about the government’s ability to implement the results in the given timeline.

Event-level coding:

Primary categories: Rights (exceptionally positive), Participation (exceptionally positive)

Primary factors: Political Equality (exceptionally positive), Civil Society (exceptionally positive), Civic Engagement (exceptionally positive)

Primary subfactors: Social Group Equality (exceptionally positive)

Secondary categories, factors and subfactors: N/A

Once factor- or subfactor-level codes have been assigned, category-level codes are calculated. If only one factor or subfactor is coded, the associated category or factor code mirrors this lower-level code. If, however, there are two or more lower-level codes, they are averaged to produce the higher-level code. Finally, countries are assessed to have an overall direction for democratic performance at the country-month level, again using the five-point scale. These overall country codes reflect the averages of the country’s multiple event reports, if relevant, or simply mirror the sole event report that month. There are cases in which analysts’ expertise overrides the mathematical average. If one factor—in case of multiple factors coded to a single event—or one event—in case of multiple event reports—has a disproportionate impact on the political landscape, analysts may decide to code the country at large to reflect that impact. It is important to note that the overall direction for democratic performance applied at the country level is limited to the specific factors of democracy and to that month and does not in any way reflect an assessment of the overall democratic performance of that country.

Coding examples

Ethiopia, August 2023

The human rights situation in Ethiopia’s Amhara region deteriorated in August, as heavy fighting broke out between the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) and Amhara militias known as Fano. The fighting follows months of tension and sporadic clashes over the federal government’s plans to disband the country’s regional forces. It began in early August when Fano fighters moved into towns and cities across the region, where they attacked police stations and regional administrators. The federal government responded by moving in the ENDF, which reportedly struck urban areas with heavy weaponry. The fighting caused large-scale civilian casualties, disrupted access to basic services and confined residents to their homes. Reports also indicate that the government shut down the Internet and used broad powers acquired under a state of emergency declared on 4 August to carry out mass arrests, with journalists and an opposition MP among those detained. The UN called for an end to the arrests and the release of those arbitrarily detained.

Event-level coding:

Primary categories: Rights (negative), Rule of Law (negative)

Primary factors: Civil Liberties (neutral), Basic Welfare (negative), Personal Integrity and Security (negative)

Primary subfactors: Freedom of Movement (negative)

Secondary categories: Rights

Secondary factors: Civil Liberties

Secondary subfactors: Freedom of Expression, Freedom of the Press

Country-level coding:

Categories: Rights (negative), Rule of Law (negative)

Overall country-month score: negative

Senegal, July 2023

Event 1

President Macky Sall announced in July 2023 that he will not seek a third term in office. He had publicly entertained the possibility of running again in 2024, claiming that the revision of the Constitution in 2016 had effectively reset presidential term limits. While Sall’s claims regarding the legality of a third term were never settled by a court, leaders including the Chairperson of the African Union Commission and the Secretary-General of the United Nations described Sall’s decision not to seek a third term as a positive example in the region.

Event-level coding:

Primary categories: Representation (positive)

Primary factors: Elected Government (positive)

Primary subfactors: N/A

Secondary categories, factors and subfactors: N/A

Event 2

Following his earlier convictions on charges of defamation (May) and corruption of youth (June), opposition politician Ousmane Sonko was arrested and faced further criminal charges at the end of July. Sonko was charged with nine serious offences, including plotting an insurrection and criminal association with terrorists. Sonko has been a frontrunning candidate for the 2024 presidential election, but his past convictions may disqualify him.

Following the latest charges against Sonko, the political party he leads, Patriots of Senegal (PASTEF), was legally dissolved through a decree issued by the Interior Minister. The day after Sonko’s latest arrest, prominent journalist Papé Alé Niang was also arrested and charged with calling for insurrection. Niang had posted a video on social media discussing Sonko’s case. Both Sonko and Niang began hunger strikes soon after being arrested.

Event-level coding:

Primary categories: Rights (negative), Representation (negative)

Primary factors: Civil Liberties (negative), Free Political Parties (negative)

Primary subfactors: Freedom of Expression (negative), Freedom of the Press (negative)

Secondary categories: Rule of Law

Secondary factors: Personal Integrity and Security

Secondary subfactors: N/A

Country-level coding:

Categories: Representation (neutral), Rights (negative)

Overall country-month score: Negative

4.4. Other elements of event reports

4.4.1. Updates

Considering that months are the Democracy Tracker’s units of time, reports are only updated after publication on an exceptional basis. When there is a new development related to an already published standard event report, an update is provided in the original report. The update is labelled as such and includes the date of the update.

For ‘to watch’ reports, generally, new information related to an ongoing process that is expected to impact the status quo will be included in the Democracy Tracker as a new standard report that conveys the end or closure of that process and the original ‘to watch’ report will be included as a source to the new report. In exceptional circumstances, when a new development is considered crucial for users’ understanding of the process that is being followed but the process as such is still ongoing, concise updates may be added to the original report and are also labelled and dated.

In election reports regarding countries where run-off elections are held, a single report with the initial results is published and will include an update with the final run-off results that is labelled and shows the date of the update.

4.4.2. Tags

In addition to coding the relevance of the events to the categories and factors of democracy, analysts also assign tags to the events that facilitate searching and filtering the data later. These tags include important concepts and political institutions, and the names of people (such as heads of government) and institutions (such as courts, electoral authorities and political parties) that are named in the reports. Events that are relevant to more than one country are tagged as ‘transnational’. Sustainable Development Goals goals 5, 10 and 16 are also tagged to event reports coded with corresponding categories, factors and subfactors of the GSoD conceptual framework, to enable further research and contribute to monitoring the Sustainable Development Goals.

4.4.3. Icons

Icons are applied by analysts to the reports of the three exceptional types of events: (a) events to watch; (b) red flagged events; and (c) national elections. ‘To watch’ reports and national elections reports have been described above. The Democracy Tracker applies red flags to notably egregious events, including assassinations of national politicians, coups d’état or other unconstitutional regime changes, outbreaks of severe intrastate or interstate hostilities, or reports of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes or ethnic cleansing from authoritative sources such as the UN. Please note that attempted political assassinations are usually coded as

4.4.4. Archived sources

The source material for the event reports is almost without exception online. As online media sites are subject to various interruptions and URL changes, analysts are required to archive reliable sources for the events and to provide links to the archived pages in the event reports. The Democracy Tracker uses Perma.cc for this purpose. This is a subscription-based service developed and maintained by the Harvard Law School Library in conjunction with other university law libraries in the United States and has significant contingencies in place to ensure link accessibility even if the initiative shuts down at some point. Articles with paywalls and licensed content are also archived with Perma.cc (even if the entire content is not visible). Users with the relevant subscription can access the full article directly from the source.

4.5. Quality control

Difficult decisions are made at two stages of the Democracy Tracker data collection and reporting process, namely (a) in choosing which events to report; and (b) in interpreting the significance of those events. DA regional analysts in the project team make these calls in the first instance. However, the DA senior adviser, the Democracy Tracker Coordinator and the Head of the DA Unit (‘quality controllers’) check the event reports for accuracy and quality. In this way, at least five individuals have verified each of the event reports.

Each month, the DA analysts complete their research, consult regional colleagues and partners (as necessary), draft their reports and code the impact of the events. These first drafts are reviewed by the DA senior adviser, the Democracy Tracker Coordinator and the Head of the DA Unit. In especially sensitive or controversial cases, these first drafts are also reviewed by regionally based colleagues and International IDEA’s Director of Global Programmes. These quality controllers verify the accuracy of the reporting, confirm or amend the directional codings and more broadly ensure that the event reports are of a high quality. It is common at this stage that quality controllers suggest dropping several event reports that do not meet the standard of signalling a significant change in the status quo. After this first round of review, the analysts edit the event reports to incorporate the changes requested by the quality controllers and resubmit the event reports for a second review. During this second review, quality controllers verify that the changes they requested have been completed and again review the overall quality of the reporting. When necessary, a second round of revisions may take place. Event reports are not published until they receive final clearance from the Democracy Tracker Coordinator and the Head of the DA Unit.

4.6. Staff

The Democracy Tracker is maintained by the DA Unit at International IDEA’s Global Programmes division in Stockholm. The DA Unit ensures gender parity among its staff, who come from and have professional experience in a diverse array of countries representing all the regions covered by the Democracy Tracker. Work for the Democracy Tracker is overseen by the Head of the DA Unit and coordinated by a designated adviser. The data collection, reporting and quality control tasks are assigned to regional subteams. These groupings follow International IDEA’s broad regional divisions: Africa and Western Asia, Americas, Asia and the Pacific, and Europe. An adviser and associate programme officer are responsible for the primary data collection, with the adviser overseeing the overall regional work. The senior adviser, the Democracy Tracker Coordinator and the Head of the DA Unit are responsible for quality control.

Additional oversight and guidance will be provided by a steering committee set up by International IDEA. The goal is for this committee to validate the research methods used in the Democracy Tracker and oversee the management of findings that are politically sensitive. The development of this committee is under discussion.

4.7. Workflow

The various elements of the monthly reporting process are described in more detail in the subsequent sections of this guide. However, the basic steps in the process are depicted in the workflow schematic in Figure 4.4.

4.8. Developing and validating the methodology

In developing and validating the Democracy Tracker methodology, International IDEA consulted peer organizations that have developed similar tools, as well as expert methodologists in academia. Select examples include the International Crisis Group’s CrisisWatch tool and Uppsala University’s Uppsala Conflict Data Program.

5.1. Country pages

5.1.1. Country profile overview

Monthly event reports are featured on individual country pages. Each country page includes qualitative and quantitative background data to provide an overview of the country’s democracy landscape, as described below.

5.1.2. Country briefs

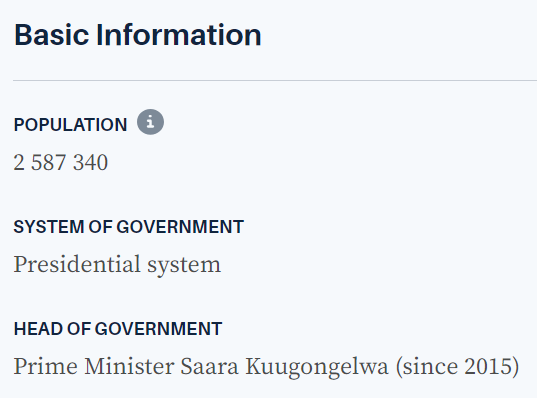

Each country page features a brief that sets out the country’s political context. Among other things, the briefs describe how the country performs at the category level, recent trends in the annual GSoD Indices data, relevant socio-political history, politically salient social cleavages, primary drivers of politics and an outlook on political developments to watch over the next 10 years. As an example, the first paragraph of the country brief for Namibia is copied in Figure 5.1.

5.1.3. Basic information boxes

Complementing the narrative text of the country briefs are a series of key data points describing the institutional features of a country’s political system, recent elections, the representation of women in the legislature and the country’s engagement with the UN’s Universal Periodic Review (a mechanism for reviewing member states’ human rights records). The information is updated using the sources listed in Annex B.

5.1.4. Human rights treaty boxes

Users are given a further indication of how countries engage with the international human rights system through summary information on the ratification status of three sets of human rights treaties—the UN’s core international human rights treaties, the International Labour Organization’s Fundamental Conventions and the principal regional human rights treaties. This information is updated annually using the sources listed in Annex C. An example of a country’s ratification status of human rights treaties is shown in Figure 5.3.

5.1.5. Global State of Democracy Indices data

The country pages also feature visualizations of key GSoD Indices data. The global ranking data show the country’s ranking per category of democratic performance from the most recent data set. Trendlines show the country’s performance on the GSoD Indices’ four categories since 1975 to date. A spider chart offers the user an overview of the state of democracy in the country, illustrating performance levels across the GSoD Indices’ 17 factors of democracy. An interactive slider allows users to produce a spider chart for any year.

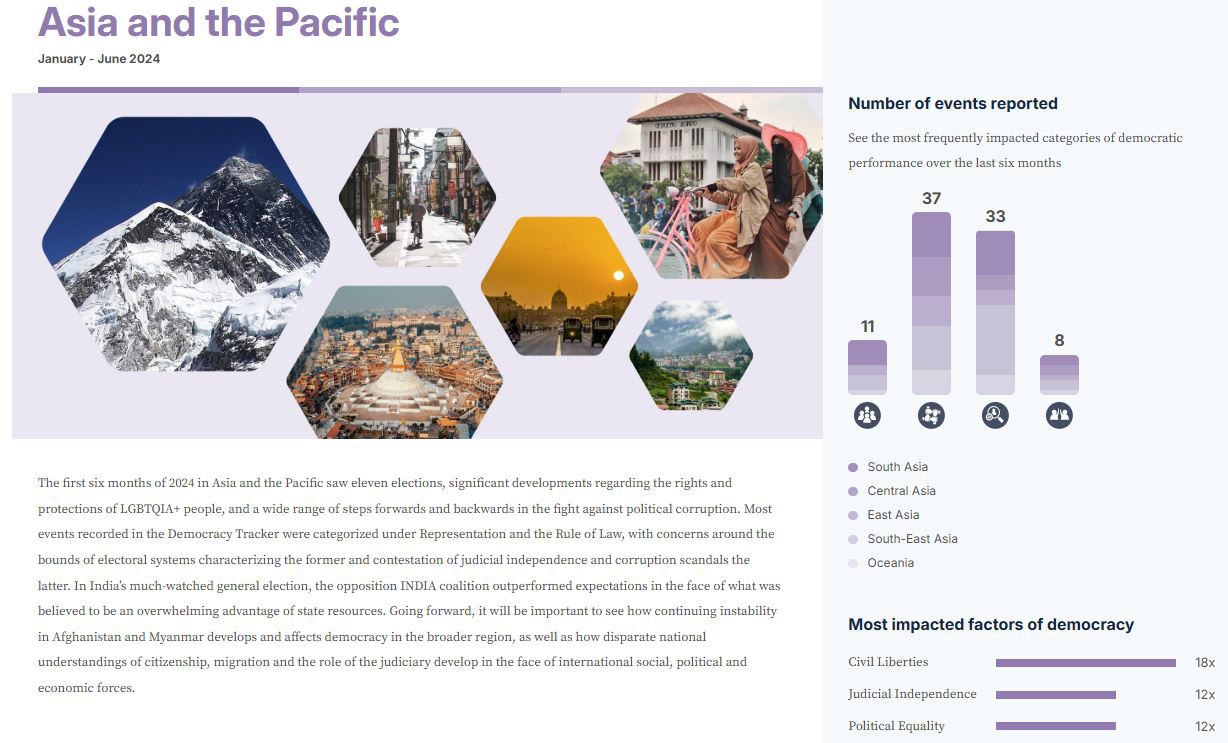

5.2. Regional and global pages

In addition to country pages, the Democracy Tracker offers regional and global summary pages on a biannual basis. Regional and global pages highlight and analyse the most important trends from the last six months, as well as what to watch. They also feature visual data, including a spider chart which shows regional or global averages of the 17 factors from the latest data set, as well as bar charts with the most frequently impacted categories and factors of democratic performance.

5.3. Data archive

In addition to being published on the relevant country profile pages and the main content on the home page, event reports are accessible to users in a data archive. There, users are able to filter the event reports and download them as a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet.

When a user downloads the data archive, the file will include the variables listed in Table 5.1.

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| country_name | The short name of the country for which the event was reported |

| region_name | The name of the region in which the event was reported |

| month | The month in which the event took place |

| year | The year in which the event took place |

| upload_date | The date on which the event was added to the Democracy Tracker database |

| event_title | A short description of the event |

| event_text | A summary of what took place in the event (generally 500–1,000 characters) |

| url | The location on the Democracy Tracker website where the event report can be found |

| tags | A list of proper nouns, event types and concepts that are relevant to the event, separated by commas |

| red_flag_value | A binary record of whether or not a red flag icon was applied to the event (1=red flag, 0=no red flag) |

| to_watch | A binary record of whether or not a ‘to watch’ icon was applied to the event (1=indicator applied, 0=not applied) |

| election | A binary record of whether or not an election icon was applied to the event (1=election, 0=no election) |

| representation | Records the directional coding for the Representation category. When the category is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| rights | Records the directional coding for the Rights category. When the category is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| rule_of_law | Records the directional coding for the Rule of Law category. When the category is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| participation | Records the directional coding for the Participation category. When the category is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| credible_elections | Records the directional coding for the Credible Elections factor. When the factor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| inclusive_suffrage | Records the directional coding for the Inclusive Suffrage factor. When the factor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| free_political_parties | Records the directional coding for the Free Political Parties factor. When the factor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| elected_government | Records the directional coding for the Elected Government factor. When the factor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| effective_parliament | Records the directional coding for the Effective Parliament factor. When the factor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| local_democracy | Records the directional coding for the Local Democracy factor. When the factor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| access_to_justice | Records the directional coding for the Access to Justice factor. When the factor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| civil_liberties | Records the directional coding for the Civil Liberties factor. When the factor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| basic_welfare | Records the directional coding for the Basic Welfare factor. When the factor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| political_equality | Records the directional coding for the Political Equality factor. When the factor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| judicial_independence | Records the directional coding for the Judicial Independence factor. When the factor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| personal_integrity_ and_security | Records the directional coding for the Personal Integrity and Security factor. When the factor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| predictable_enforcement | Records the directional coding for the Predictable Enforcement factor. When the factor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| absence_of_corruption | Records the directional coding for the Absence of Corruption factor. When the factor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| civil_society | Records the directional coding for the Civil Society factor. When the factor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| civic_engagement | Records the directional coding for the Civic Engagement factor. When the factor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| electoral_participation | Records the directional coding for the Electoral Participation factor. When the factor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| freedom_of_expression | Records the directional coding for the Freedom of Expression subfactor. When the subfactor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty. |

| freedom_of_the_press | Records the directional coding for the Freedom of the Press subfactor. When the subfactor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| freedom_of_association _and_assembly | Records the directional coding for the Freedom of Association and Assembly subfactor. When the subfactor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| freedom_of_religion | Records the directional coding for the Freedom of Religion subfactor. When the subfactor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| freedom_of_movement | Records the directional coding for the Freedom of Movement subfactor. When the subfactor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| social_group_equality | Records the directional coding for the Social Group Equality subfactor. When the subfactor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| gender_equality | Records the directional coding for the Gender Equality subfactor. When the subfactor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

| economic_equality | Records the directional coding for the Economic Equality subfactor. When the subfactor is not relevant to the event, the cell is empty |

5.4. Monthly alerts

The alert system allows users to receive a customized selection of reports every month. Users are able to select parameters tailored to their interests, including the regions and countries, aspects of democracy, positive/neutral/negative events and election reports.

The following countries are included in the Democracy Tracker’s monthly reporting:

| Afghanistan | Albania | Algeria |

| Angola | Argentina | Armenia |

| Australia | Austria | Azerbaijan |

| Bahrain | Bangladesh | Barbados |

| Belarus | Belgium | Benin |

| Bhutan | Bolivia | Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| Botswana | Brazil | Bulgaria |

| Burkina Faso | Burundi | Cabo Verde |

| Cambodia | Cameroon | Canada |

| Central African Republic | Chad | Chile |

| China | Colombia | Comoros |

| Congo | Costa Rica | Côte d’Ivoire |

| Croatia | Cuba | Cyprus |

| Czechia | Democratic People’s Republic of Korea | Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| Denmark | Djibouti | Dominican Republic |

| Ecuador | Egypt | El Salvador |

| Equatorial Guinea | Eritrea | Estonia |

| Eswatini | Ethiopia | Fiji |

| Finland | France | Gabon |

| Gambia | Georgia | Germany |

| Ghana | Greece | Guatemala |

| Guinea | Guinea-Bissau | Guyana |

| Haiti | Honduras | Hungary |

| Iceland | India | Indonesia |

| Iran | Iraq | Ireland |

| Israel | Italy | Jamaica |

| Japan | Jordan | Kazakhstan |

| Kenya | Kosovo | Kuwait |

| Kyrgyzstan | Lao People’s Democratic Republic | Latvia |

| Lebanon | Lesotho | Liberia |

| Libya | Lithuania | Luxembourg |

| Madagascar | Malawi | Malaysia |

| Maldives | Mali | Malta |

| Mauritania | Mauritius | Mexico |

| Mongolia | Montenegro | Morocco |

| Mozambique | Myanmar | Namibia |

| Nepal | Netherlands | New Zealand |

| Nicaragua | Niger | Nigeria |

| North Macedonia | Norway | Oman |

| Pakistan | Palestine | Panama |

| Papua New Guinea | Paraguay | Peru |

| Philippines | Poland | Portugal |

| Qatar | Republic of Korea | Republic of Moldova |

| Romania | Russian Federation | Rwanda |

| Saudi Arabia | Senegal | Serbia |

| Sierra Leone | Singapore | Slovakia |

| Slovenia | Solomon Islands | Somalia |

| South Africa | South Sudan | Spain |

| Sri Lanka | Sudan | Suriname |

| Sweden | Switzerland | Syrian Arab Republic |

| Taiwan | Tajikistan | Tanzania |

| Thailand | Timor-Leste | Togo |

| Trinidad and Tobago | Tunisia | Türkiye |

| Turkmenistan | Uganda | Ukraine |

| United Arab Emirates | United Kingdom | United States |

| Uruguay | Uzbekistan | Vanuatu |

| Venezuela | Viet Nam | Yemen |

| Zambia | Zimbabwe |

| Description | Sources | Frequency of update/verification |

|---|---|---|

| Population | World Bank | Once a year, based on the World Bank population data |

| System of government | CIA The World Factbook | Once a year |

| Head of government | Democracy Tracker monthly event report research; official government sites | Following presidential/legislative elections |

| Head of government party | Democracy Tracker monthly event report research; official government sites | Following presidential/legislative elections |

| Electoral system for lower or single chamber | International IDEA Electoral System Design Database | Once a year |

| Women in lower or single chamber | Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) | Following legislative elections |

| Women in upper chamber | Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) | Once a year for all countries + following legislative elections at the country level |

| Last legislative election | Democracy Tracker monthly event report research; IFES Election Guide, Recent and Upcoming Elections | Once a year for all countries + following legislative elections at the country level |

| Effective number of political parties | Trinity College Dublin Election Indices; legislature websites as necessary | Following legislative elections |

| Head of state | Democracy Tracker monthly event report research; official government sites | Following presidential elections/changes in the monarch |

| Selection process for head of state | International IDEA ConstitutionNet Head of State selection process | Once a year |

| Latest Universal Periodic Review (UPR) date | UN Human Rights Council Universal Periodic Review | Once a year |

| Latest UPR percentage of recommendations supported | UN Human Rights Council Universal Periodic Review | Once a year |

Table C.1. UN’s core international human rights treaties

Table C.2. International Labour Organization fundamental conventions

Table C.3. Regional human rights conventions

The following CAMEO codes are used to filter data from GDELT for analysis.

| 024 | Appeal for political reform |

|---|---|

| 0241 | Appeal for leadership change |

| 0243 | Appeal for rights |

| 0244 | Appeal for change in institutions, regime |

| 0251 | Appeal for easing of administrative sanction |

| 0252 | Appeal for easing of political dissent |

| 0253 | Appeal for release of persons or property |

| 034 | Express intent to institute political reform, not specified below |

| 0341 | Express intent to change leadership |

| 0342 | Express intent to change policy |

| 0343 | Express intent to provide rights |

| 0344 | Express intent to change institutions, regime |

| 0811 | Ease restrictions on political freedoms |

| 0812 | Ease ban on political parties or politicians |

| 0814 | Ease state of emergency or martial law |

| 082 | Ease political dissent |

| 0831 | Accede to demands for change in leadership |

| 0833 | Accede to demands for rights |

| 0834 | Accede to demands for change in institutions, regime |

| 092 | Investigate human rights abuses |

| 094 | Investigate war crimes |

| 1041 | Demand change in leadership |

| 1042 | Demand policy change |

| 1043 | Demand rights |

| 1044 | Demand change in institutions, regime |

| 1052 | Demand easing of political dissent |

| 1122 | Accuse of human rights abuses |

| 113 | Rally opposition against |

| 123 | Reject request or demand for political reform, not specified below |

| 1231 | Reject request for change in leadership |

| 1233 | Reject request for rights |

| 1234 | Reject request for change in institutions, regime |

| 1242 | Refuse to ease popular dissent |

| 1321 | Threaten with restrictions on political freedoms |

| 1322 | Threaten to ban political parties or politicians |

| 1323 | Threaten to impose curfew |

| 1324 | Threaten to impose state of emergency or martial law |

| 133 | Threaten with political dissent, protest |

| 140 | Engage in political dissent, not specified below |

| 141 | Demonstrate or rally, not specified below |

| 1411 | Demonstrate for leadership change |

| 1412 | Demonstrate for policy change |

| 1413 | Demonstrate for rights |

| 1414 | Demonstrate for change in institutions, regime |

| 1421 | Conduct hunger strike for leadership change |

| 1422 | Conduct hunger strike for policy change |

| 1423 | Conduct hunger strike for rights |

| 1424 | Conduct hunger strike for change in institutions, regime |

| 1431 | Conduct strike or boycott for leadership change |

| 1432 | Conduct strike or boycott for policy change |

| 1433 | Conduct strike or boycott for rights |

| 1434 | Conduct strike or boycott for change in institutions, regime |

| 1441 | Obstruct passage to demand leadership change |

| 1442 | Obstruct passage to demand policy change |

| 1443 | Obstruct passage to demand rights |

| 1444 | Obstruct passage to demand change in institutions, regime |

| 145 | Protest violently, riot, not specified below |

| 1451 | Engage in violent protest for leadership change |

| 1452 | Engage in violent protest for policy change |

| 1453 | Engage in violent protest for rights |

| 1454 | Engage in violent protest for change in institutions, regime |

| 1721 | Impose restrictions on political freedoms |

| 1722 | Ban political parties or politicians |

| 1723 | Impose curfew |

| 1724 | Impose state of emergency or martial law |

| 175 | Use tactics of violent repression |

| 176 | Attack cybernetically |

| 1822 | Torture |

| 1831 | Carry out suicide bombing |

| 1832 | Carry out vehicular bombing |

| 1833 | Carry out roadside bombing |

| 1834 | Carry out location bombing |

| 185 | Attempt to assassinate |

| 200 | Use unconventional mass violence, not specified below |

| 201 | Engage in mass expulsion |

| 202 | Engage in mass killings |

| 203 | Engage in ethnic cleansing |

| 204 | Use weapons of mass destruction, not specified below |

| 2041 | Use chemical, biological, or radiological weapons |

| 2042 | Detonate nuclear weapons |

Different types of sources and data sets

The GSoD Indices summarize information from 165 indicators collected from 24 data sets. Some of these indicators, such as the elected office and direct democracy indicators from V-Dem, are composite measures based on several subindicators. The data sets listed in Table E.1 represent four different types of source data:

- Expert surveys (ES). In these surveys, country experts assess the situation on a particular issue in a country. This kind of data is provided by V-Dem and the ICRG.

- Standards-based ‘in-house coding’ (IC). This type of coding is carried out by researchers and/or their assistants based on an evaluative assessment of country-specific information found in reports, academic publications, reference works, news articles, and so on. This kind of data is provided by V-Dem, Polity5, Lexical Index of Electoral Democracy (LIED), CIRIGHTS, Civil Liberty Dataset (CLD), Bjørnskov-Rode regime data (BRRD), Political Terror Scale (PTS) and Media Freedom Data (MFD). Freedom in the World and the BTI are classified as ‘in-house coding’ in the rest of this document, but it should be noted that their internal processes involve both country experts and in-house review and revision, meaning that their coding processes are between these first two categories.

- Observational data (OD). This is data on directly observable features such as the ratio of women to men in parliament, infant mortality rates and legislative elections. This kind of data is provided by V-Dem, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx), World Health Organization (WHO), International Labour Organization (ILO) and the UN Statistics Division.

- Composite measures (CM). These are based on a number of variables that come from different existing data sets rather than original data collection. This kind of data is provided by V-Dem in the form of an elected officials index, a direct democracy index, and a local government index.

| Data set | Data provider | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) | Bertelsmann Stiftung | <https://bti-project.org> |

| Bjørnskov-Rode Regime Data (BRRD) | Bjørnskov and Rode | <http://www.christianbjoernskov.com/bjoernskovrodedata> |

| Child Mortality Estimates (CME) | UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation | <https://childmortality.org> |

| CIRIGHTS | Mark, Cingranelli, Filippov and Richards | <https://cirights.com> |

| Civil Liberties Data set (CLD) | Møller and Skaaning | <http://ps.au.dk/forskning/forskningsprojekter/dedere/data sets> |

| Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Food Balances | Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) | <https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/FBS> |

| Freedom in the World | Freedom House | <https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world> |

| Freedom on the Net | Freedom House | <https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net> |

| Global Educational Attainment Distributions | Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IMHE) | <https://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/ihme-data/global-educational-attainment-distributions-1970-2030> |

| Global Findex Database | World Bank | <https://data.worldbank.org> |

| Global Gender Gap Report | World Economic Forum | <https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2022> |

| Global Health Observatory | World Health Organization (WHO) | <https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/indicator-groups/indicator-group-details/GHO> |

| Global Media Freedom Data set (MFD) | Whitten-Woodring and Van Belle | <https://faculty.uml.edu//Jenifer_whittenwoodring/MediaFreedomData_000.aspx> |

| ILOSTAT | International Labour Organization (ILO), Department of Statistics | <https://ilostat.ilo.org> |

| International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) | Political Risk Services | <http://epub.prsgroup.com/products/icrg> |

| Lexical Index of Electoral Democracy (LIED) | Skaaning, Gerring and Bartusevičius | <http://ps.au.dk/forskning/forskningsprojekter/dedere/data sets> |

| Political Terror Scale (PTS) | Gibney, Cornett, Wood, Haschke, Arnon and Pisanò | <http://www.politicalterrorscale.org> |

| Polity5 | Marshall, Jaggers and Gurr | <http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscrdata.html> |

| Standardized World Income Inequality Database (SWIID) | Solt | <https://fsolt.org/swiid> |

| United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) statistics | UNESCO | <http://data.uis.unesco.org> |

| United Nations E-Government Survey | UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs | <https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/en-us/Reports/UN-E-Government-Survey-2022> |

| Varieties of Democracy data set | V-Dem Project | <https://www.v-dem.net> |

| Voter Turnout Database | International IDEA | <https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/voter-turnout> |

| World Population Prospects (WPP) | UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division | <https://population.un.org/wpp> |

Absence of Corruption

Corruption disrupts the effective functioning of democratic institutions by introducing partiality and arbitrariness in the application of laws and distribution of resources. This kind of activity can undermine popular control over decision making, hindering the ability of opposition parties, civil society, independent media and the population at large to hold the government accountable.

When public officials engage in the arbitrary exercise of power, for example by using state resources for personal benefit or by rewarding allies, decisions are not made in the public interest and are instead driven by personal or political motives (Huntington 1996). This fosters favouritism and personalism (Rose-Ackerman 1999) often resulting in a lack of accountability. Fundamentally, corruption undermines the principle of equality before the law—a fundamental pillar of democracy.

Such dynamics also undermine policy effectiveness, exacerbate inequality and prevent democratic governments from meeting the needs of their citizens (Mauro 1995), eroding public trust in institutions and threatening the legitimacy of democratic institutions (Norris 2011).

Definition: Absence of Corruption measures the degree to which public officials (including elected representatives and public servants) abuse their positions through the arbitrary exercise of power for illicit personal or political gain. It also includes lax or selective enforcement of relevant laws intended to prevent significant acts of corruption in the private sector.

What the Democracy Tracker measures: The primary focus is on events that shed light on corrupt activities, events that address (investigate, prosecute, etc.) cases of corruption and strengthen/weaken laws that regulate corrupt activities.