Beijing+30: Taking Stock of Progress on Gender Equality Using the Global State of Democracy Indices

Technical Paper, March 2025

The Beijing Declaration in 1995 recognized that gender equality is essential to democracy. Yet, 30 years later, progress remains uneven and at risk, with backlash against gender equality and democratic values threatening hard-won gains. Drawing on the Global State of Democracy Indices, produced by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA), this technical paper explores advances, setbacks and gaps in gender equality and women’s political participation since 1995. As threats to gender equality and democracy grow, the 2025 Political Declaration of the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) must reaffirm that women’s equal participation in decision making is fundamental to democracy—and that both gender equality and democracy must be protected (UN Economic and Social Council 2025).

In 2025 the world marks 30 years since the adoption of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, which established a landmark agenda for women’s empowerment. Coinciding with the 30th anniversary of International IDEA—the only intergovernmental organization with the sole mandate to strengthen democracy—this milestone reaffirms the 1995 declaration that women’s equal participation in decision making, alongside equal rights, opportunities and access to resources, is essential for democracy, peace and human rights, ensuring a just society that protects the interests of all. The importance of gender equality was also reaffirmed by all UN member states in the 2030 Agenda, in particular through Sustainable Development Goal 5 and its targets 5.1. and 5.5, which emphasize the elimination of all forms of discrimination and the promotion of women’s political participation as key targets for achieving inclusive and sustainable development.

1. Progress since 1995

Data from the Global State of Democracy (GSoD) Indices (International IDEA n.d.a) shows that since the adoption of the Beijing Declaration in 1995, the world has made some progress in advancing gender equality, though significant challenges remain. During this period, the global average for gender equality rose by 19 per cent, with progress in all regions, but at a slower pace than the 33 per cent increase in the previous 20 years (from 1975 to 1995). For an explanation of what dimensions are measured in International IDEA’s gender equality index, see Box 1.

Box 1. Gender Equality measure in the Global State of Democracy Indices

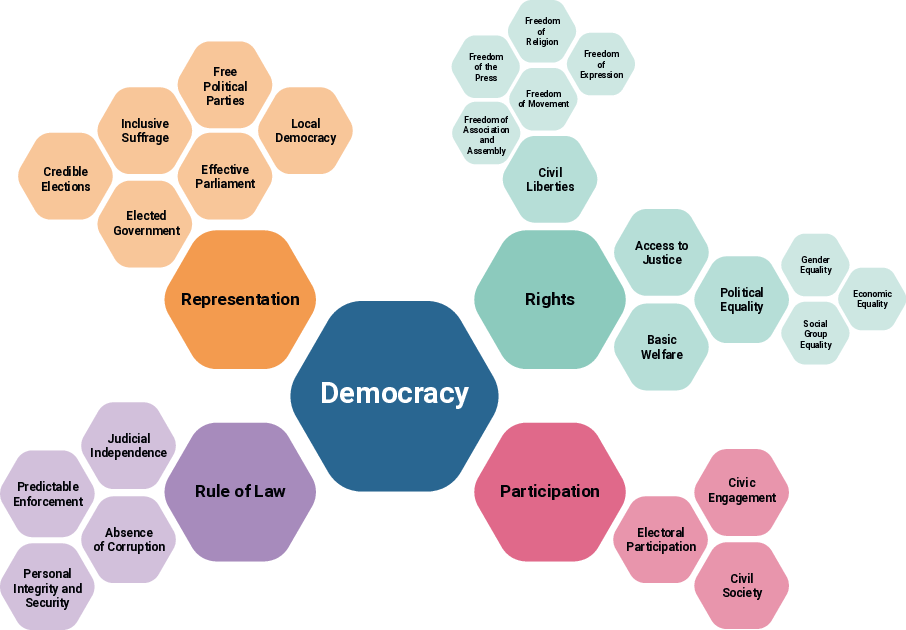

International IDEA’s democracy framework recognizes gender equality as a vital pillar of democracy. The Global State of Democracy Indices measure democracy across four key dimensions—Representation, Rights, Rule of Law and Participation—using 29 indicators of democratic quality—one of which is Gender Equality. These indicators are aggregated from 165 base indicators that are given a score from 0 to 1, indicating low, mid-range or high performance.

The framework evaluates 174 countries from 1975 until the most recent update in 2023. Each country is given a score for Gender Equality, a subfactor under Political Equality in the Rights dimension. Based on 11 indicators from six sources (the V-Dem Institute, the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, the CIRIGHTS Data Project, the Global Gender Gap Report, the International Labour Organization and the World Bank), it includes expert-coded measures of power distribution by gender and of female participation in civil society, alongside observational indicators such as the female-to-male ratio of mean years of schooling, women’s representation in legislatures, labour force participation, the percentage of women in managerial positions and gender-disaggregated control of financial accounts. Additional indicators capture gender-based exclusion, women’s empowerment, and political and economic rights. When references are made in the analysis to percentage changes in Gender Equality, they refer to the global, regional or country-level GSoD scores on this measure over time, with 1995 as a baseline and up to 2023 (the latest GSoD Indices update) (Skaaning and Hudson 2024).

Progress in gender equality has been uneven, with stark disparities across regions. Over the past 30 years, only Europe has improved its gender equality performance from mid-range to high. The Americas lag behind in the mid-range but perform above the global average, while the Asia-Pacific and Africa, also in the mid-range, perform below the global average. The Middle East, despite making the largest relative gains, has moved only from very low to low levels, remaining the furthest behind in terms of expanding opportunities for women and protecting their rights. Hence, persistent challenges remain—especially in the Middle East and Africa, where no country has achieved high levels of gender equality.

| 1995 | 2023 | % change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| World | 0.48 | 0.57 | +19 |

| Africa | 0.40 | 0.48 | +20 |

| Americas | 0.52 | 0.61 | +17 |

| Asia and the Pacific | 0.44 | 0.52 | +18 |

| Middle East | 0.27 | 0.34 | +26 |

| Europe | 0.64 | 0.74 | +16 |

Several countries—spanning Africa, the Americas, the Asia-Pacific and the Middle East—have made remarkable progress in gender equality over the past 30 years. According to the GSoD Indices, the 10 countries with the most significant gains (measured over different time periods) are Bhutan, Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador, The Gambia, Guyana, Indonesia, Morocco, Sierra Leone and Taiwan. With few exceptions, these countries have also undergone democratic consolidation following a transition to democracy, highlighting the connection between democratic progress and gender equality advancements. In Chile, for example, improvements can be attributed to legal reforms (with the legalization of divorce in 2004, among other reforms), increased female political participation (women’s parliamentary representation rose from 7 per cent in 1995 to 35 per cent in 2025), expanded access to education and employment, and policies addressing gender-based violence and discrimination (IPU 2025; World Bank n.d.). Taiwan (now ranked 16th in the world in gender equality) has also made significant strides through legal reforms ensuring workplace rights and political representation; education and economic advancements promoting women’s participation; LGBTQIA+ rights, including same-sex marriage; and protections against gender-based discrimination and violence (World Bank 2024).

| Country | % increase | 1995 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morocco | 74 | 0.27 | 0.47 |

| Sierra Leone | 73 | 0.30 | 0.52 |

| Chile | 60 | 0.45 | 0.72 |

| Taiwan | 59 | 0.54 | 0.86 |

| The Gambia | 58 | 0.36 | 0.57 |

| Indonesia | 56 | 0.34 | 0.53 |

| Bhutan | 55 | 0.38 | 0.59 |

| Bolivia | 54 | 0.37 | 0.57 |

| Ecuador | 51 | 0.37 | 0.56 |

| Guyana | 49 | 0.41 | 0.61 |

| Kenya | 46 | 0.37 | 0.54 |

| Dominican Republic | 45 | 0.38 | 0.55 |

| Peru | 45 | 0.44 | 0.64 |

While most countries have made progress in gender equality over the past 30 years, some—spanning all regions and diverse contexts of economic and democratic development—are now worse off than they were three decades ago. Hungary, Palestine, South Sudan, Syria, Vanuatu and Yemen stand out as the most severe cases of decline over the past three decades (although from different starting points, with Hungary falling in the mid-range, compared with the low performance of the others). Additionally, several countries—Afghanistan, Algeria, Belarus, Burkina Faso, El Salvador, Haiti, Nicaragua, Niger, Russia, Sudan, Venezuela and Zimbabwe—have experienced recent setbacks that are of great concern. With the exception of Algeria and Belarus, every country on this list scores lower today than 30 years ago. The decline in many of these countries has been driven by conflict (e.g. Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Haiti, Sudan), autocratization (e.g. Nicaragua, Russia, Venezuela) or democratic backsliding (e.g. El Salvador, Hungary), with some countries facing multiple overlapping challenges.

Even in countries that have experienced significant economic growth in recent decades, progress in gender equality has sometimes lagged behind. Azerbaijan, China, India, Israel, Japan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Russia and Turkey have all struggled to translate economic gains into significant advancements in gender equality over the past 30 years. While the United States of America has demonstrated borderline high performance in gender equality, it has made slow progress in the past 30 years and still lags considerably behind (0.7) the average for Western Europe (0.86).

2. Where does the world stand today?

While the regional average for the Americas and the Asia-Pacific remains in the mid-range, some countries stand out as gender equality bright spots. Although more than three quarters of high-performing countries are in Europe, notable examples can also be found in the Americas (Costa Rica, which ranks among the top 12 in the world, Argentina, Barbados, Canada, Cuba, Jamaica, Uruguay, and the USA) and the Asia-Pacific (New Zealand and Taiwan). Costa Rica, for example, ranks high in gender equality due to its strong legal framework promoting women’s rights (including a law against gender-based violence, passed in 2022), high levels of female political representation (49 per cent women in parliament), progressive social policies supporting education and healthcare, and robust labour protections ensuring economic opportunities for women (IPU 2025; United States of America 2022).

| Country | Gender Equality score | Country | Gender Equality score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norway | 0.99 | Italy | 0.78 | |

| Sweden | 0.94 | Moldova | 0.77 | |

| Denmark | 0.94 | Canada | 0.77 | |

| Australia | 0.92 | Ireland | 0.77 | |

| Latvia | 0.90 | Barbados | 0.77 | |

| Germany | 0.89 | Bulgaria | 0.76 | |

| Spain | 0.89 | Malta | 0.76 | |

| Netherlands | 0.89 | Luxembourg | 0.76 | |

| Slovenia | 0.89 | United Kingdom | 0.75 | |

| France | 0.88 | Portugal | 0.75 | |

| Costa Rica | 0.87 | Uruguay | 0.73 | |

| New Zealand | 0.87 | Croatia | 0.73 | |

| Estonia | 0.87 | Georgia | 0.73 | |

| Belgium | 0.86 | Ukraine | 0.73 | |

| Iceland | 0.86 | Czechia | 0.73 | |

| Taiwan | 0.86 | Greece | 0.72 | |

| Finland | 0.85 | Chile | 0.72 | |

| Austria | 0.84 | Argentina | 0.72 | |

| Switzerland | 0.82 | Cuba | 0.71 | |

| Lithuania | 0.82 | Serbia | 0.71 | |

| Jamaica | 0.80 | USA | 0.70 |

Significant disparities also exist within regions, which is concerning, as subregional gaps can hinder overall progress and create strongholds of persistent inequality. For example, deep-seated gender inequality is entrenched in the Pacific, which lags 40 per cent behind the regional average. Significant gender equality gaps of around 30 per cent can be found in Eastern and North-western Europe, North and Central America, South and East Asia, and Northern and Southern Africa.

Gender equality generally aligns with democratic performance, though there are exceptions. Of the 42 countries with high levels of gender equality, all but Cuba are democracies. Conversely, nearly all low-performing countries are autocracies, except for three Pacific Island countries—Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu—where gender equality remains fragile. Democracies typically achieve greater gender equality by upholding rights, representation and inclusive governance, while autocracies, which restrict political participation and social freedoms, tend to lag behind (International IDEA 2019). However, democratic maturity alone is not enough: sustained progress requires political commitment supported by effective policies.

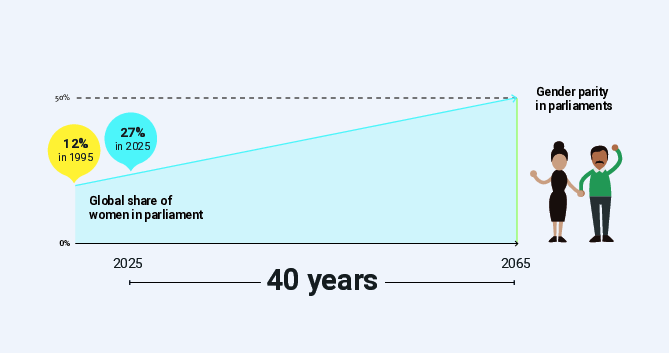

Women remain significantly under-represented in political decision making, despite progress over the past 30 years. A key measure of gender equality is women’s presence in formal political structures, which strengthens democracy by bringing diverse perspectives, elevating new issues and reshaping citizen–representative relationships. Women’s parliamentary representation has more than doubled over the past 30 years, rising from 12 per cent globally in 1995 to 27 per cent in 2025 (IPU 2025). However, it remains below the 30 per cent target set in 1995, with full parity still a distant goal. At the current pace, equal representation in parliaments is projected to take another 40 years (see Figure 2).

There are stark differences in women’s parliamentary representation by region. Despite the fact that gender equality performance is higher overall in Europe, the Americas is the region with the highest percentage of women parliamentarians, at 35 per cent, followed by Europe, at 32 per cent. The Middle East lags far behind the other regions, at 17 per cent. Andorra and Mexico are the only countries with democratically elected parliaments to have reached parity, and Bolivia, Costa Rica and Iceland are just below the 50 per cent mark. In 2025 there are still countries with no women in their parliaments (Oman, Tuvalu, Yemen), and the Maldives, Papua New Guinea and Vanuatu have only 2–3 per cent women parliamentarians (IPU 2025).

The 2024 super-cycle of elections failed to turbocharge women’s political representation, delivering only modest gains. With 74 national elections and 1.6 billion ballots cast worldwide, progress towards gender parity remained sluggish in 2024, with women’s legislative representation rising by less than 1 percentage point ahead of the Beijing Declaration’s 30th anniversary. The number of women heads of state or government increased from six to nine—out of 195 UN countries and observer states—an improvement, albeit still insufficient. However, key milestones included Claudia Sheinbaum’s election as Mexico’s first female president, Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah’s historic win as Namibia’s first female president (and the first in Southern Africa) and Kamala Harris’s candidacy as only the second woman to be the nominee for a major party in a US presidential election (International IDEA n.d.b).

Gender quotas have been a key driver of progress in women's parliamentary representation. Their adoption has expanded rapidly, with 71 per cent of countries implementing some form of quota by 2022. In 2022 countries with legally binding quotas had higher average female representation (31 per cent) than those without (26 per cent) (Ahrens and Erzeel 2024). In 2024 this gap persisted, with women voted into power holding 30 per cent of the seats in lower or single chambers with quotas, versus just 22 per cent in countries without quotas (International IDEA n.d.b). Mongolia’s 2024 parliamentary elections saw women’s representation rise from 17 per cent to 25 per cent after 2023 electoral reforms introduced a 30 per cent candidate quota, set to increase to 40 per cent by 2028. However, Finland, South Africa and the United Kingdom surpassed 40 per cent female representation in 2024 without quotas, highlighting that, while gender quotas are a powerful tool, they are not the only path to more inclusive parliaments (International IDEA n.d.b).

Parity laws are another legislative measure designed to ensure equal representation of women and men in political offices (often mandating that electoral candidate lists alternate between genders). Countries that have adopted such laws include Argentina, Bolivia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, France and Mexico. As backlash against gender equality increases, however, such laws are coming under threat. Argentina, for example, has expressed intentions to repeal its parity law, reflecting a broader agenda aimed at rolling back certain gender equality measures. This proposal is part of a series of actions, including plans to remove the legal classification of femicide from the penal code (International IDEA 2024b; Barber 2025).

Women’s participation in civil society and their civil liberties are facing growing threats amid democratic backsliding and shrinking civic space. Although women’s participation in civic life is essential for vibrant democracies, more countries have been moving towards authoritarianism than democracy over the past decade (International IDEA 2024a), restricting civic space and disproportionately impacting women and their organizations, which are often the most vulnerable, least resourced and least networked. While women’s participation in civil society has risen by 18 per cent since 1995, this is a significantly slower pace than the previous 30 years, which saw a more than 10-fold increase, with a recent downward trend threatening advances. At the same time, women’s civil liberties1 have also suffered, with the global score dropping by 2 per cent since 2018, particularly in the Americas and the Asia-Pacific. Women’s freedom of discussion2 has also suffered, falling by 28 per cent since 2012, with troubling declines across the Americas, the Asia-Pacific, the Middle East and Europe. These trends signal a troubling erosion of hard-won gains in women’s political rights and civic engagement (V-Dem n.d.).

Rising violence against women in politics is a barrier to political participation, threatening both gender equality and democracy. Over the past decade, this trend has surged, fuelled by online harassment (Ríos Tobar 2024), political polarization and weakening democratic norms—an issue largely unforeseen when the Beijing Declaration was adopted 30 years ago. A 2016 Inter-Parliamentary Union global study found that a significant portion of women parliamentarians face harassment and abuse. These aggressions—including, in the worst cases, lethal threats—deter women from running for office or participating in civic life, ultimately undermining inclusive democracy. Despite record numbers of women engaging in elections, they face an escalating backlash, while efforts to monitor and combat political violence remain inadequate. Many parliaments lack internal mechanisms to address harassment, and election monitoring standards often overlook gendered violence. This issue persists unchecked owing to a lack of comprehensive global data. Moreover, as donors scale back gender-focused programmes, support for women facing political violence is further at risk. Without urgent action to strengthen data collection, institutional accountability and international support, the democratic gains of recent decades will continue to erode (Zamfir 2024; United Nations General Assembly 2018).

3. Conclusion

Despite notable progress, gender equality in politics remains fragile, with persistent disparities across regions and a troubling rise in violence against women in politics. While gender quotas and legal reforms have contributed to increased representation, systemic barriers, including harassment and political violence, continue to deter women’s political participation. The lack of comprehensive global data further hinders efforts to address these challenges, allowing gender-based violence and exclusion to persist unchecked. As donor support for gender-focused programmes declines and gender equality measures face backlash, urgent action is needed to safeguard past gains, ensure equal political participation, and uphold democracy’s fundamental promise of inclusive political representation and participation. In this context, the CSW’s 2025 Political Declaration should honour the Beijing Declaration by reaffirming that women’s equal participation in decision making is essential to democracy and that both gender equality—in politics and elsewhere—and democracy need to be protected against increasing threats.

References

Ahrens, P. and Erzeel, S., Beyond Numbers: Stories of Gender Equality in and through Parliaments (Stockholm: International IDEA and Inter Pares, 2024), <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2024.58>

Barber, H., ‘Milei government plans to remove femicide from Argentina penal code’, The Guardian, 29 January 2025, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/jan/29/argentina-femicide-womens-rights-law>, accessed 1 March 2025

International IDEA, Global State of Democracy Indices, 1975–2023, v. 8, [n.d.a], <https://www.idea.int/democracytracker/gsod-indices>, accessed 1 March 2025

—, The 2024 Global Elections Super-Cycle, [n.d.b], <https://www.idea.int/initiatives/the-2024-global-elections-supercycle>, accessed 1 March 2025

—, The Global State of Democracy 2019: Addressing the Ills, Reviving the Promise (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2019), <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2019.31>

—, The Global State of Democracy 2024: Strengthening the Legitimacy of Elections in a Time of Radical Uncertainty (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2024a), <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2024.55>

—, ‘Argentina – June 2024’, Global State of Democracy Initiative, June 2024b, <https://www.idea.int/democracytracker/report/argentina/june-2024>, accessed 1 March 2025

Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), Sexism, Harassment and Violence against Women Parliamentarians (Geneva: IPU, 2016), <https://www.ipu.org/resources/publications/issue-briefs/2016-10/sexism-harassment-and-violence-against-women-parliamentarians>, accessed 1 March 2025

—, ‘Monthly ranking of women in national parliaments’, February 2025, <https://data.ipu.org/women-ranking/?date_year=2025&date_month=02>, accessed 1 March 2025

Ríos Tobar, M., Violencia política de género en la esfera digital en América Latina [Gender-based political violence in the digital sphere in Latin America] (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2024), <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2024.93>

Skaaning, S.-E. and Hudson, A., The Global State of Democracy Indices Methodology: Conceptualization and Measurement Framework, Version 8 (Stockholm: International IDEA, 2024), <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2024.43>

United Nations Economic and Social Council, Commission on the Status of Women, ‘Political Declaration on the Occasion of the Thirtieth Anniversary of the Fourth World Conference on Women’, E/CN.6/2025/L.1, 6 March 2025, <https://docs.un.org/en/E/CN.6/2025/L.1>, accessed 16 March 2025

United Nations General Assembly, ‘Report of the Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women, its Causes and Consequences on Violence against Women in Politics’, A/73/301, 6 August 2018, <https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1640483?v=pdf>, accessed 1 March 2025

United States of America, Department of State, ‘Costa Rica 2022 Human Rights Report’, 2022, <https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/costa-rica/>, accessed 12 March 2025

UN Women, Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action: Beijing +5 Political Declaration and Outcome (New York: United Nations, 2015), <https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2015/01/beijing-declaration>, accessed 1 March 2025

Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute, Country Graph, [n.d.], <https://www.v-dem.net/data_analysis/CountryGraph/>, accessed 1 March 2025

World Bank, Gender Data Portal, ‘Chile’, [n.d., <https://genderdata.worldbank.org/en/economies/chile>, accessed 12 March 2025

—, ‘Women, Business and the Law 2024: Taiwan, China’, 2024, <https://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/sites/wbl/documents/pilot/2024-nov-14/WBL24_2-0_Taiwan-china.pdf>, accessed 12 March 2025

Zamfir, I., ‘Violence against Women Active in Politics in the EU: A Serious Obstacle to Political Participation’, European Parliamentary Research Service, February 2024, <https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2024)759600>, accessed 1 March 2025

Acknowledgements

This technical paper was written by Annika Silva-Leander and was reviewed by Seema Shah.

About the author

Annika Silva-Leander is Head of North America at International IDEA where she oversees International IDEA’s outreach in the region. She is also International IDEA’s Permanent Observer to the United Nations. Between 2018 and 2021, Silva-Leander was the Head of International IDEA’s Democracy Assessment Unit in Stockholm where she led the work on the Global State of Democracy report. From 2015 to 2018, she worked as the Senior Adviser to the Secretary-General of International IDEA.

- According to the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute, women’s civil liberties are ‘understood to include freedom of domestic movement, the right to private property, freedom from forced labor, and access to justice’ (V-Dem n.d.).

- According to V-Dem, this indicator specifies ‘the extent to which women are able to engage in private discussions, particularly on political issues, in private homes and public spaces without fear of harassment by other members of the polity or the public authorities’ (V-Dem n.d.).

© 2025 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members.

With the exception of any third-party images and photos, the electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0>.

Design and layout: International IDEA

ISBN: 978-91-7671-901-5 (PDF)

ISBN: 978-91-7671-902-2 (HTML)

DOI: <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2025.12>