Voter turnout statistics provide us with a rough indicator of citizen participation in electoral processes. Looking back at 2015, to what extent did African voters participate on election day, and what conclusions can we draw from this?

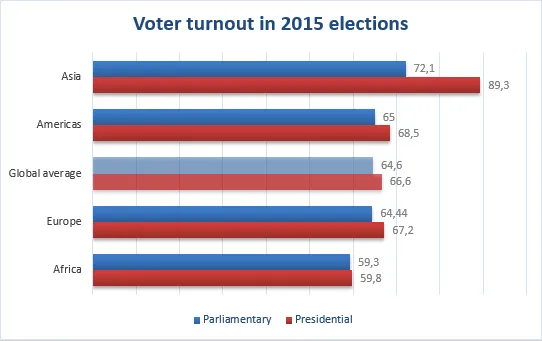

Altogether 16 countries organized national-level elections in Africa last year – counting both presidential and parliamentary elections. Turnout averaged nearly 60 per cent for both types of elections. This is slightly lower than the global average of 67 and 65 per cent for presidential and parliamentary elections, respectively. Turnout in Africa remains low compared to other world regions. In Asia, for example, the turnout averaged 89 per cent for presidential elections and 72 per cent for parliamentary elections.

The snap presidential elections held in the Seychelles in December last year scored highest at 90 per cent. The small island state also displayed the most competitive elections of the year on the continent. With a winning margin of 0.15 per cent (just above 4,000 votes), it is not surprising that voters turned up on election day to have their say. Notably, the Seychelles presidential elections have historically gathered considerable engagement with turnout remaining above 85 per cent throughout the history of competitive elections.

Similarly competitive elections explain the highest turnout increase in Tanzania. Incumbent President Jakaya Kikwete was banned from running for a third term and the fight between the top candidates was fierce. For the run-off election 67 per cent of registered voters made it to the polling, up from 43 per cent in 2010.

Zambia, on the other hand, recorded the lowest turnout in the country’s history with only 32 per cent casting their vote on election day. Compared to t54 per cent in 2011, this represented a significant drop. In Sudan and Cote d’Ivoire turnout also decreased considerably – by 26 and 28 percentage points, respectively, compared to their previous presidential elections in 2010. Given the very competitive nature of the presidential elections in Nigeria, it is somewhat surprising to note that even here turnout dropped by 10 percentage points.

Big variations in turnout are also visible when scrutinizing turnout in parliamentary elections across the continent – from 93 per cent in Ethiopia to 28 per cent in Egypt. Trends over time show that turnout in Ethiopia has remained above 90 per cent throughout all elections except in 2005 when elections were marred by widespread violence. Such high and persisting turnout levels are rare not only in Africa but throughout the globe. Parliamentary elections in Egypt, on the other hand, seem to be plagued by the lack of engagement with the elections organized in 2005 and 2010 also being below 30 per cent – representing some of the lowest figures on the continent.

Taking a quick glimpse at turnout from a sub-regional perspective over the past 25year period shows variations. On average, Southern Africans tend to participate in elections at a higher frequency . West Africans, on the other hand, were less likely to turn up at the ballot box. Turnout in the region was nearly 17 percentage points lower for parliamentary elections and 11 percentage points lower for presidential elections compared to the same figures from Southern Africa. Turnout in Northern Africa is comparable to that of West Africa whereas citizens in Central and Eastern Africa take part to a greater extent than in North Africa, though not as much as voters in Southern Africa.

After 25 years – have elections outlived their role in Africa?

Turnout statistics over time show some variations – with the continental average for presidential elections sitting above 68 per cent in the first generation of multiparty elections in the early 1990s to 63 per cent in the last five-year period. Fluctuations in countries over the past years have been significant and it is therefore too early to point to a clear-cut trend. At the same time, however, democracy and electoral stakeholders ought to be very much aware of the situation, track turnout developments and prepare to engage in more comprehensive interventions to bolster citizen interest and participation in the electoral processes.

On the other hand, policy makers must ensure that elections matter. Election promises must produce hands-on resultsand deliver security, infrastructure, housing, healthcare, education, water and electricity to the population as well as rule of law and good governance. In short – elections must contribute to improving lives and livelihoods and to deepening democratic developments.