Is the space for civil society really shrinking?

For democracies to thrive, a vibrant and actively engaged citizenry and civil society are essential. Civil society can monitor and hold the state to account, it can infuse a greater diversity of voices into the policy process, and it can act as a force for democratic reform or provide resistance to democratic backsliding.

The space for civil society to play this role and for critical civic voices to make themselves heard is however, shrinking in many countries. This often goes hand in hand with democratic backsliding, where governments with a formal democratic façade, resort to measures (often through legal means) that restrict critical voices in the public sphere.

Two dimensions of International IDEA’s recently launched Global State of Democracy Indices directly cover aspects about the state of civil society. Firstly, the ‘Freedom of Association and Assembly’ dimension (within the Fundamental Rights attribute, and the Civil Liberties sub-attribute) measures how freely civil society organisations are allowed to form. Secondly, the ‘Civil Society Participation’ dimension falls under the Participatory Engagement attribute, and measures the extent to which organised, voluntary, self-generating and autonomous social life is dense and vibrant in a given country. All scoring in the indices runs from 0 to 1, with 0 representing the lowest achievement in the whole sample and 1 the highest (read more on the indices methodology).

The Global State of Democracy Indices. show a strong theoretical link between the two dimensions of Freedom of Assembly and Association and Civil Society Participation as well as a statistical correlation. If a government is successful in controlling the establishment and operation of civil society organisations (often, but not only through legal means) and in using repression tactics against them, then one could expect to see a subsequent decrease in civil society participation over time. However, the Civil Society Participation variable is also determined by a number of other factors, including political culture and the history of civil society in a given country, as well as the nature and openness of the policy-making process to non-state actors. Therefore, when a country is backsliding democratically, one could expect to see a consequential decrease in its freedom of assembly score, as those rights can be overturned fairly quickly, while changes in civil society participation may not be seen immediately and are more likely to be observed over a longer period of time.

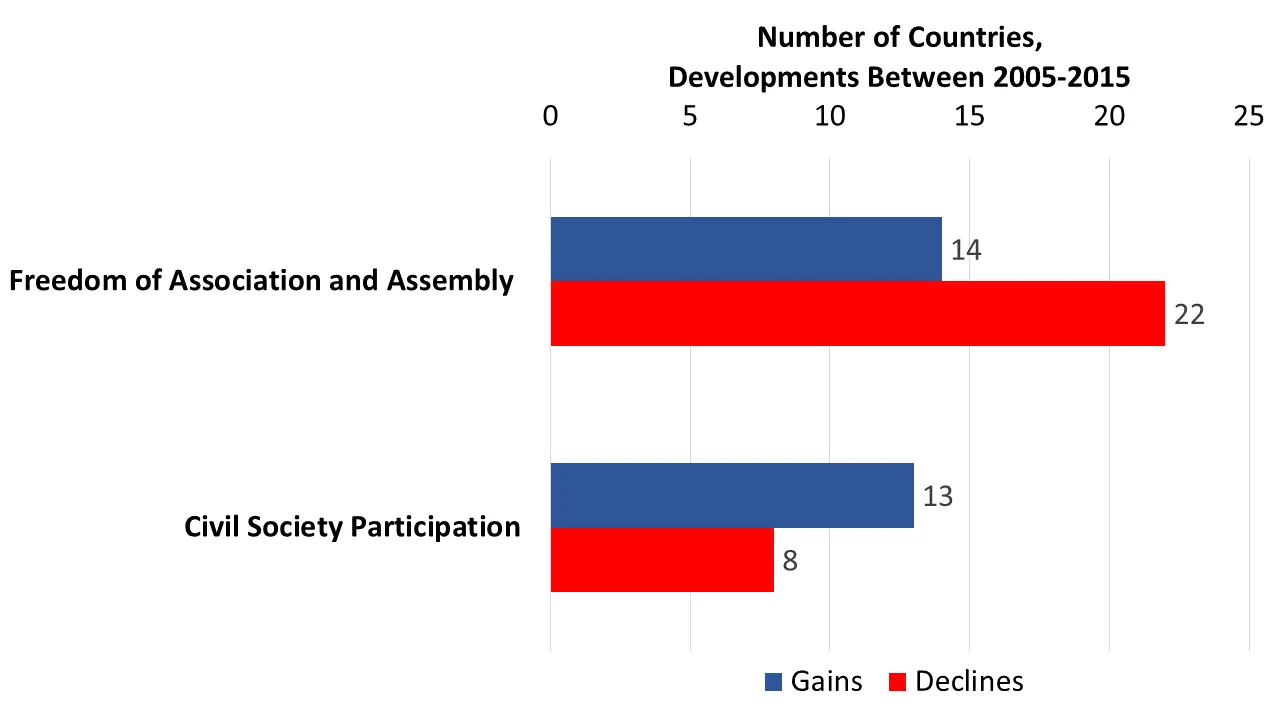

Seen from a historical perspective, the data shows that both Civil Society Participation and Freedom of Association and Assembly have improved globally since 1975, the so-called ‘third wave of democracy. From 1975 to 2015, the global average of Freedom of Association Assembly improved from 0.43 to 0.64. A similar increase is noted for the Civil Society Participation variable which rose from the same baseline by several points to 0.63 in 2015. This is most likely due to democratic advances worldwide, with a growth in the number of countries in which competitive elections determined government power, from only a quarter of the world’s countries in 1975 to two thirds in 2016. The transition to democratic systems of government tend to lead to an expansion of political and civil rights and space for civil society organizations to form and flourish. When we look at the last decade (2005-2015), a total of 13 countries have increased their civil society participation, while eight 8 have seen a decline. However, for freedom of association and assembly, there are some worrying trends with more countries that have seen declines (22) than gains (14).

Despite the long-term global increases, there are still widespread regional disparities on both of Civil Society Participation and Freedom of Association and Assembly. In 1975, the Middle East and Iran, followed by Africa, scored well below the world average, while Asia and the Pacific scored somewhat below and Latin America slightly below on both dimensions. North America and Europe scored significantly above the world average on both. Since then, there are some advances worth praising, but also some worrying regional developments. There are also wide variations between countries in each region and between sub-regions.

In 2015, the Middle East and Iran is the region under the world average that has advanced the slowest on both dimensions since 1975 and continued to have the widest distance to the world average in 2015. The distance to the world average is actually wider now on both dimensions than 40 years ago. One country that has seen gains in Freedom of Association and Assembly in the past decade is Lebanon, after the end of the Syrian occupation in 2005. Yemen is the country that has experienced the most significant decline in the same variable, since 2012, after the revolution. Three countries in the region score among the lowest 10% in the world on both dimensions, including Oman, Saudi Arabia, and Syria. Iran scores in the bottom 10% on Freedom of Association and Assembly and this is the case for Qatar on Civil Society Participation.

Asia and the Pacific’s distance to the world average has widened between 1975 and 2015. The region does include some countries that have seen their scores improve significantly since 2005 though. These include Myanmar on both dimensions since 2009, pre-dating the democratic transition; Sri Lanka on both dimensions since 2014; Nepal on Freedom of Association and Assembly after the peace accords in 2005; as well as Laos, although from a low baseline. However, countries with significant declines in the past decade include Cambodia since 2011 (due to democratic backsliding and closing of the democratic and civic space), Thailand on Freedom of Association and Assembly after the democratic backsliding process initiated in 2012, with Thailand now scoring in the bottom 10% on this dimension; and Pakistan declining significantly on Freedom of Association and Assembly since 2012. India has also seen a decline in Freedom of Association and Assembly and Civil Society Participation since 2010, with the use of restrictive legislation for registration and operation of Civil society organisations and restrictions on foreign funding to these organisations. Asia and the Pacific’s development on Freedom of Association is hampered by authoritarian regimes such as China, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and North Korea which persistently score in the bottom 10% for Freedom of Association and Assembly globally.

Africa’s distance to the global average has narrowed since 1975 on Freedom of Association and Assembly. It is the region after Latin America that has seen the largest score increase in this dimension since the 1970s. On Civil Society Participation, Africa has caught up with the global average. This reflects the democratic expansion in the region in the last 40 years, which has opened the space for civil society organizations to form, operate, engage in the public debate, monitor and hold the state to account and deliver services. The countries in the region that have seen the most gains in the past decade on Freedom of Association and Assembly are Lesotho, Nigeria, Botswana, Libya since the fall of Gadaffi seven years ago (although this should be interpreted with caution, as the country has fallen into deep internal strife since), and some gains for Eritrea, although the country still ranks in the world’s bottom 10% on both dimensions. The countries that have seen significant gains in Civil Society Participation are Libya, Lesotho, Gabon, Benin, Cote d’Ivoire and Chad. Four countries in the region score among the top 10% in the world on Freedom of Association and Assembly, including Ghana, Botswana, Lesotho and Liberia. While, Benin, Niger and Sierra Leone are among the top 10% in Civil Society Participation. However, some countries in the region have also seen significant declines in Freedom of Association and Assembly in the past decades. These include Egypt, Burundi, Mali, Swaziland, South Africa, Republic of Congo, Mauritania, and Uganda. The countries that score in the bottom 10% on both dimensions are Eritrea and South Sudan. Those that score in the bottom 10% on Freedom of Association and Assembly include Egypt, Burundi, Swaziland as well as Ethiopia. For Civil Society Participation, Gambia (before the democratic transition) scored in the bottom 10%.

Latin America has seen the largest increase of all regions in Freedom of Association and Assembly score (from 0.42 in 1975 to 0.71 in 2015). Freedom of Association and Assembly was slightly below the world average in 1975 and it is now significantly above it. Civil Society Participation was slightly above the world average in 1975 and it is now somewhat above. Freedom of Association and Assembly improved steadily in the region until 1996 (to a peak of 0.76), when it started to slowly decline (0.71 in 2015). The countries that have seen significant gains in Freedom of Association and Assembly in the past decade are Colombia, with the end of the civil war and the signing of the peace agreement. The countries where a decline is noted in the past decade however, are Ecuador, Nicaragua, Bolivia, and to some extent Peru. Venezuela has continued its decline on Freedom of Association and Assembly (initiated in 1998-2000) and has since experienced a continuous gradual decline on this indicator moving from 0.53 in 2005 to 0.44 in 2015. Venezuela’s 2015 score on this variable is almost half of what it was in 1997 (0.82). The country in the region that scores in the world’s bottom 10% on Freedom of Association and Assembly is Cuba. Some of the region’s countries do score in the top 10%; Costa Rica on both dimensions and Chile and Jamaica on Freedom of Association and Assembly.

North America is the region with the highest score in Freedom of Association and Assembly both in 1975 and now. There has been a decline from 2001, at a peak of 0.94 down to 0.89 in 2015, although this decline is not statistically significant.

Europe started at a lower level of Freedom of Association and Assembly in 1975 than North America, with many of its countries still under one-party communist regimes. The gap has narrowed since then and has seen an overall increase from 0.59 in 1975 to 0.75 in Freedom of Association and Assembly in 2015 and from 0.55 to 0.69 on Civil Society Participation. The countries in the region that have seen significant gains in the past decade in the first variable are Moldova, Croatia and Albania and in civil society participation: Ireland, Croatia and Ukraine. The country that has seen a decline in both Freedom of Association and Assembly and Civil Society Participation in the past decade is Turkey, moving from somewhat above the European average to significantly beneath it. Albania, Serbia and Azerbaijan have seen declines in Freedom of Assembly and Association and Russia, Macedonia and Ukraine in Civil Society Participation. For both Freedom of Association and Assembly and Civil Society Participation Azerbaijan falls within the bottom 10% globally. The region also has a number of top 10% performers: Norway, Sweden, Switzerland Latvia, Estonia and Slovenia on freedom of association and assembly and on Civil Society Participation: Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Germany, Switzerland, Ireland, Belgium, Greece and Slovenia.

While the Global State of Democracy Indices are currently updated only until 2015, more recent data sources point to continued restrictions to civic space around the world. CIVICUS’ State of Civil Society Report 2018 finds that the majority of countries in the world (109) are seeing “serious, systemic problems with their civic space” and they also point the worrying development of shrinking civic space in countries where they were rarely seen before. Efforts are needed to counteract the shrinking civic space around the world, if democratic consolidation is to take root against backsliding tendencies.