Philippine constitution after 30 years: Time to review?

Attempts to amend the 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines is nothing new. Previous administrations have pushed for opening up the constitution in reference to varying political reasons, but have not been successful. This time around, however, the reason of opening up the constitution for review is centered on a campaign promise by President Rodrigo Duterte to adopt federalism. He believes this change in the form of government is the only hope to achieve lasting peace and development in the conflict-afflicted area of Muslim Mindanao, and to basically de-centralise powers from the capital of Manila.

Most of the discussions around charter change have focused on the choices between a presidential and parliamentary form of government, and between a modified unitary and federal system. Other options in constitutional reform areas have neither been fully explored, nor have the implications of the proposed shifts on other institutional features and practices, such as the electoral system, articulated. Even less examined is the whole framework of making and unmaking constitutions – what does constitution building entail? And a more significant question is how the push for federalism affect other reform agendas such as the Bangsamoro political entity?

Under this premise, International IDEA together with the Department of Political Science of the University of the Philippines-Diliman and the Political Science Program of the College of Social Sciences at the University of the Philippines-Cebu organized a public forum on Philippine Constitution @30: Institutional Choices in a Time of Change, in celebration of the 30th year of the Philippine Constitution.

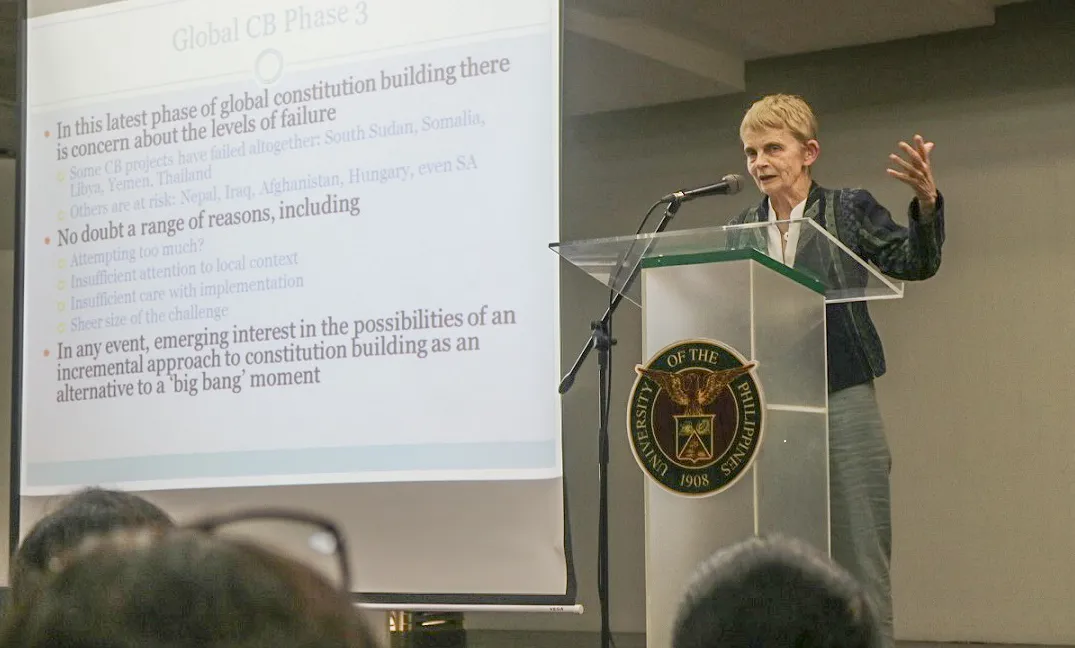

Cheryl Saunders, Laureate Professor Emeritus at Melbourne Law School and senior technical advisor to the constitution-building programme of International IDEA, discussed constitution-building in comparative perspective. Professor Saunders put the constitution building in the Philippines in the context of developments of constitution-building around the world, particularly from Asia-Pacific region. She also opened up discussions how global experiences in constitution building may be of use to the current debate in the Philippines.

Professor Saunders highlighted the three phases of constitution building in the Philippines and how and where it linked and overlapped with global constitution building. Interesting that during the time Philippine constitution was ratified, it was also in the 1980s that transition from authoritarianism to democracy was on the rise. And while reviewing the Philippine constitution started to gain ground in 1990s in line with intensive peace agreements for Muslim Mindanao, it also broadly coincided with constitutions and peacemaking at the global stage. Currently, there is wide debate on the process and substance of constitutional change to pave way for President Duterte’s federalism initiative; while at the same time the perceived emergence between ‘big bang’ constitution building and incrementalism.

The idea of ‘big bang’ approach as demonstrated by recent attempts of constitution building such as those that did not work out as expected (i.e. South Sudan, Libya, Yemen and Thailand) and those at risk such as Nepal, Afghanistan and Hungary, among others. Saunders brought forward the idea of incremental approach to constitution building. Incrementalism may mean: Amendments to an existing Constitution rather than making a new one; Reforming or adapting existing institutions rather than adopting significant new ones or deferring particular contentious decisions. The Philippines is not alone in this discourse, neighboring countries such as Sri Lanka, South Korea and Myanmar are also in constitution building discussions. Professor Saunders stressed that any approach taken in constitution building must need to weigh pros and cons, in light of international experience and must be distinct to Philippine context.

Professor Saunders also discussed forms of devolution, which has become a feature in constitution building to overcome conflict. Professor Saunders explained the options for devolution – federalism and special autonomy – where significant local autonomy is needed, that comes in different forms, and requires both levels of government to have capacity and work effectively. There much discussion and questions from the audience on how federalism works for Philippine scenario.

“If building federation from a unitary state, it is a long transition period. It is not a matter of adopting a model, there is no model fit for all”, says Saunders.

But she emphasized that transforming to federalism depends much on local context, and how the Philippines will develop the system. It would require strong leadership and established administrative systems and structures in place.

The forum also included Paul Hutchcroft, Professor of Political Science and Social Change at the Australian National University, who spoke about federalism in the context of Philippine politics and other forms of political reform. Hutchcroft emphasized that federalism in the Philippines would require existing regional divide but strengthened administrative structures. Even then, federal system has to be continually be renegotiated as demonstrated by the evolution of the US federalism. At the same time, he suggested the paradox behind decentalisation that would still require strong and capable central state “able to enforce the rules which authority is being devolved to the subnational level”.

Both experts agreed that if the Philippines do decide to go down the path of federalizing the country, it has to prepare now - strengthen the current regional bureau, and regional councils’ planning processes to establish better structures. It will be a long process, but only Philippine citizens and its leaders could decide which system works best for its context.