When Nepal promulgated its new constitution in September last year, some gender equality advocates in the country felt that it didn’t go far enough to ensure gender equality. While it provides quotas for women’s political participation in the federal and provincial legislatures and in local governing bodies it does not require them to be in leadership positions. Unequal citizenship provisions for women and men have attracted concern, and are not in alignment with the broader guarantees for gender equality found elsewhere in the constitution.

The national constitution is a primary tool for countries implementing Sustainable Development Goal 5 Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. As Nepal begins its process of constitutional implementation, it must confront how the equality provided for in its constitution can be ensured in reality.

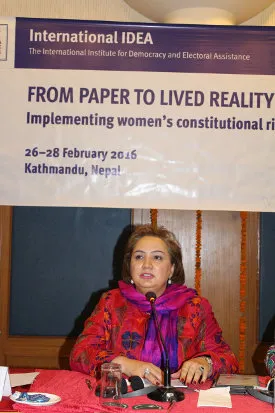

The consensus that emerged at International IDEA’s workshop From paper to lived reality: Implementing women’s constitutional rights, held in Kathmandu, Nepal in February is clear. The ever-continuous work on the implementation of constitutional guarantees is as important as constitutional design for gender equality and women’s rights. As one speaker from Nepal, the country with the newest constitution said:

“The real work for achieving women’s rights and gender equality begins now.”

Sharing experiences

The workshop was designed to explore the processes of constitutional implementation from the perspective of achieving substantive equality. Participants looked at facilitating factors and challenges, constitutional design options that facilitate gender-responsive implementation and the roles of institutional actors and civil society in overcoming these challenges.

Perspectives and experiences from Afghanistan, Costa Rica, France, Kenya, Mexico, Nepal, Tunisia and South Africa helped contrast and compare processes and outcomes in geographically and culturally diverse contexts on two framing issues: women’s right to political participation and women’s right to health.

Women’s rights to political participation

The growing consensus among states at the global level is that ‘parties must respect all measures enacted by the state to ensure gender equality in elections, including provisions regarding gender equality in candidacy and party lists’, according to the OSCE’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights. However, this has proven to be particularly difficult to implement in national level politics, where parties often ignore gender-equality principles in candidate selection and nomination processes.

Participants presented a wide range of lessons on actions to ensure party compliance with constitutional guarantees for gender equality.

Examples include efforts by Kenya’s Constitutional Implementation Commission (CIC) to push for the adoption of legislation to implement the constitutional principle that not more than two-thirds of MPs can be of same sex. Justice María del Carmen Alanis Figueroa shared how the Electoral Tribunal of the Federal Judiciary of Mexico requires all candidate lists to be based on the gender parity principle. In France, Réjane Sénac explained how the High Council on Equality works to ensure that electoral formulas and rules for all levels of decision-making are adapted to meet the constitutional standard of gender parity in political life.

Lessons and recommendations

During the workshop a number of lessons emerged, including the importance of involving a significant number of women in constitution drafting bodies to ensure gender-sensitive constitutional deliberations and outcomes. In the implementation phase, forming alliances across party and gender lines to broaden support was identified as key.

Participants at the workshop also identified the distinction between a provision that prohibits discrimination based on sex and gender and a provision that guarantee equality for women and men, noting that both provisions, capturing both negative and positive rights, are important to reach substantive equality.

Other recommendations included the adoption of provisions on gender equality that clearly allow the use of gender quotas (and preferably other measures aimed at achieving equality); sound electoral laws that appropriately implement quotas and protect women’s political participation; and the establishment of electoral justice institutions, with a clear mandate and efficient procedures to oversee and enforce women’s political rights.

Increased numerical representation does not readily result in equal power sharing between women and men in political institutions. This transformative change in established patterns of political decision-making does not happen in elected legislatures or political parties only, but takes shape through incremental improvements in women’s status in public and private spheres.

Women’s right to health

The right to health and healthcare is increasingly included in new constitutions, and is found in over 115 constitutions as either a justiciable right or an aspirational guarantee. There has been an evolution in the understanding of government’s obligation to fulfil the socio-economic right to health and healthcare and in the recognition of its justiciability, but is most frequently interpreted as a right to be progressively realized.

The importance of independent constitutional bodies in monitoring and supporting constitutional implementation of health rights was highlighted by several presenters. Catherine Mumma, former commissioner of the CIC, shared how Kenya’s constitutional drafters designed the CIC to ensure its independence and how the CIC carried out its mandate to monitor and facilitate the development of laws required for constitutional implementation. This included the decentralization of health services as Kenya implemented its new federal system. Mumma also spoke about the challenge of ensuring that executive ministries understand the rights-based approach of the new constitution and developed draft legislation and policies accordingly, emphasizing the need to for the development of the capacity of executive ministries.

In Afghanistan the importance of civil society organizations and religious leaders to the implementation of women’s health rights was highlighted. The government of Afghanistan has contracted NGOs to provide health services at the local level throughout the country, a model which has been recognized as a best practice in contexts where demand exceeds government capacity to provide services. Farhad Javid of Marie Stopes International shared how engagement with local religious leaders has been key to the successful delivery of reproductive health services in Afghanistan, especially in conflict-affected areas that are out of reach of the government.

Lessons learned

Many lessons emerged from the presentations and ensuing discussions regarding the implementation of women’s health rights. With regard to constitutional design, constitutional provisions which state that customary and religious practices must adhere to fundamental rights can be critical to protecting women and girls from harmful practices that impact their right to health, such as female genital mutilation and early marriage.

When designing health systems, it is important to have complaints procedures in place for both public and private health providers in order for the state to hold service providers accountable and to ensure that women’s health needs are met. Public interest litigation can be a powerful tool when the government fails to meet its constitutional obligations, however non-implementation of judicial decisions is a problem that can undermine its effectiveness. Independent constitutional rights bodies such as a gender commission or a human rights commission with investigative powers and a broad mandate can be effective monitoring mechanisms, and can support the government to develop responsive health legislation and policy. These bodies have the potential to be more accessible to the poor than other branches of government.

These lessons are only a handful of those that emerged from the workshop, which will be captured in a paper to be published in 2016. The paper will highlight the lessons learned from the cases shared at the workshop, as well as put forth areas for future research.