Mexico, July 1: The biggest election in Mexican history

Este artículo se encuentra disponible en Castellano.

On Sunday, July 1, Mexico went to the polls in what has been called the largest election in the country’s history. With more than 89 million on the voter rolls, 18,299 federal, state, and local offices were filled. A new president was elected and there were elections for the entire Congress (128 senators and 500 members of the lower house). At the state and local levels nine governors were elected, along with 972 members of state legislatures, and tens of thousands of municipal authorities, including mayors, municipal legal officers (síndicos), and local council members. This was an alignment never seen before, motivated in part by the recent 2014 electoral reform, with local elections in 30 of Mexico’s 32 states, in addition to the federal election nationwide. Never before has so much political power been at stake. And, according to the results released by the National Election Institute (INE), never had so much political power changed hands in a single day, in such a compelling way, in the country’s history:

The unquestionable victor of the presidential race was Andrés Manuel López Obrador, widely known as “AMLO,” of the “Together We Will Make History” Coalition (Coalición ‘Juntos Haremos Historia’: made up of the Partido Movimiento de Regeneración Nacional (MORENA), the Partido del Trabajo (PT), and the Partido Encuentro Social (PES)) with 53.19% of the votes. The last time that a Mexican presidential candidate got past the 50% barrier was back in 1988, amidst suspicions that the election results had been manipulated. Accordingly, with this vote, AMLO becomes the candidate with the most votes in the history of Mexico, with 30.1 million. Before this election the candidate with the most votes in the country’s history was the current president, Enrique Peña Nieto, who garnered just over 19 million. One factor that contributed to this was the high level of political participation, at 63.42%, similar to participation in 2012 (63.15%).

Graph 1. Mexico Elections: Rate of participation in presidential elections (2000-2018)

Source: Author’s compilation, based on data from the National Electoral Institute.

Far behind AMLO, in second and third place, were Ricardo Anaya Cortés, of the “Por México al Frente” coalition (made up of the Partido Acción Nacional (PAN), the Partido de la Revolución Democrática (PRD), and Movimiento Ciudadano (MC)), with 22.27 per cent of the votes; and José Antonio Meade, candidate of the “Todos por México” coalition (made up of the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI), the Partido Nueva Alianza (PANAL), and the Partido Verde(PV)), with 16.41 per cent, a historically low figure for the PRI (previously, the lowest figure for the presidential vote garnered by the PRI was in the 2006 election, when candidate Roberto Madrazo Pintado finished in third place with 22.26 per cent of the valid votes cast). In last place was the first independent candidate in Mexico’s history, Jaime Rodríguez Calderón, known as “El Bronco,” who won 5.2 per cent of the vote.

According to the electoral map, AMLO’s victory was also historic at the state level. His candidacy obtained the majority of votes in 30 of the 32 states in the country. The exceptions were Nuevo León and Guanajuato, where Ricardo Anaya enjoyed the advantage. AMLO even won in states such as Aguascalientes, Chihuahua, Jalisco, and Yucatán, where he had never won before and where, in 2006 and 2012, his coalition had ended in a distant third place. Candidate José Antonio Meade did not win in any state.

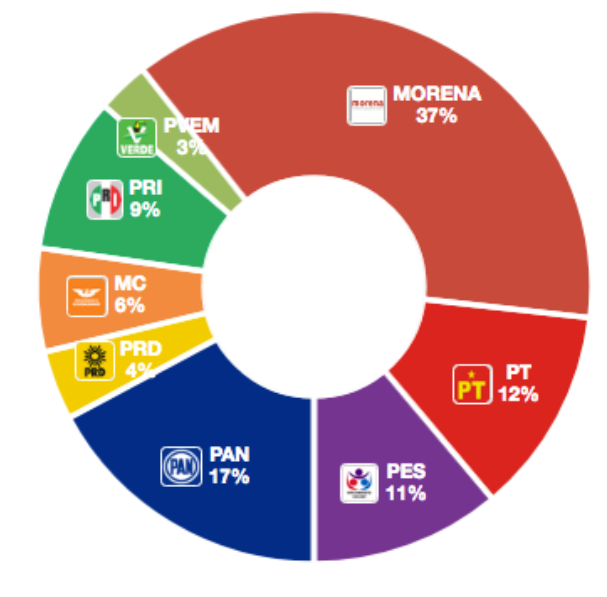

Pulled along by the AMLO effect, the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies will also have a novel configuration. In the Senate, with 128 seats, MORENA becomes the leading political force, with approximately 55 seat (with data from the Preliminary Electoral Results Program, INE-92.9 per cent of the polling places counted), which, added to the possible seats of the PES and the PT, could give him 68 seats and with that a simple majority. By way of contrast, the coalition of the PRI and its allies in the Senate elected in 2012 had 62 seats. Today, the PRI will become the third force in the Senate, with a total of approximately 13 seats. The colors also change in the Chamber of Deputies, with 500 seats. MORENA appears to have won 191, which together with those that will go to the PT and the PES (the third- and fourth-leading forces in the lower house) will yield a comfortable majority of 307 seats. The results of the 300 districts elected by relative majority are revealing. In 2015, the force with the largest vote and its coalition (PRI, Verde, and Nueva Alianza) had 185 districts. Now, the coalition headed up by MORENA appears to have 218 of these 300 districts. It is likely that the PRI will become the fifth leading force in the lower house, with a total of 45 members. Graphs 2 and 3 below show the possible configurations in the Senate and Chamber of Deputies based on the preliminary results from Sunday (when this table was drawn up the results of the district counts were not in, nor had the resolutions been issued by the Electoral Tribunal of the federal judiciary in response to challenges to the elections for legislators of both houses of Congress).

Graph 2. Composition of the Senate

Source: Sabino Bastidas, consultant.

Graph 3. Composition Chamber of Deputies

Source: Sabino Bastidas, consultant.

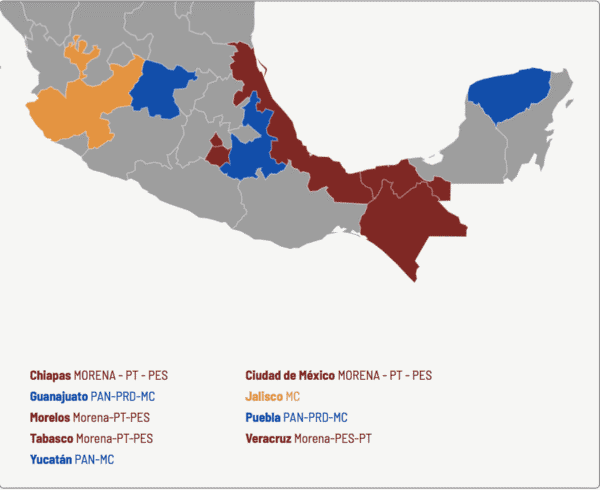

Also changing hands are most of the governorships up for election on 1 July. Of these, originally two—Guanajuato and Puebla—were in the hands of the PAN, two—Jalisco and Yucatán—were in the hands of the PRI, three—Mexico City, Morelos, and Tabasco—were in the hands of the PRD, one—Chiapas—in the hands of the Partido Verde, and one—Veracruz—in the hands of the PAN-PRD coalition. Now, five of them—Mexico City, Chiapas, Morelos, Tabasco, and Veracruz—will be governed by MORENA. The PAN, in coalition, holds on to Guanajuato and Puebla, and has won Yucatán. Movimiento Ciudadano won in Jalisco. The coalition headed up by the PRI saw no victories, reflecting the major punishment meted out by voters at the polls this time around.

Map 1. Results of the elections for governor in 9 states

Source: Animal Político

Election day, it should be noted, proceeded without any major incidents, displaying once again the capacity of Mexico’s electoral institutions. One sign of this is that 99.9 per cent of the 156,807 polling places were up and running. Also notorious is the transparency of the process, overseen by more than one million representatives of all the political parties—and representatives of independent candidates—plus more than 32,000 Mexican observers and 907 international observers.

As has been shown on several occasions, especially since 1994, the electoral authorities performed their functions adequately and professionally. Moreover, the contest was held in fair conditions: all the political parties had good access to radio and television, media coverage was on a level playing field, and they received generous public funds. In addition, in the presidential race three debates were held with a large audience in the different media, using novel formats that encouraged debate and brought differences among the candidates into relief.

Nonetheless, special mention must be made of two negatives: political violence and vote-buying. As for violence, it is worrisome that during the nine months of the election process there were 135 assassinations of politicians, 48 of them candidates and pre-candidates for elective office. This of course is not the result of the elections, but it does reflect the country’s public security problems. As for efforts to buy votes, the survey drawn up by the organization Acción Ciudadana Frente a la Pobreza revealed that during 2018, 10.2 per cent of the population received some gift, service, favor, or work from some political party, while an encouraging 17.3 per cent rejected them.

While these two issues go beyond the electoral institutions, now that the elections are over one must conduct a thorough analysis, evaluating what went right and areas of opportunity. A new election reform—especially after the implementation of the 2014 electoral reform—that makes adjustments to the well-oiled election procedures may be a good start for this new administration.