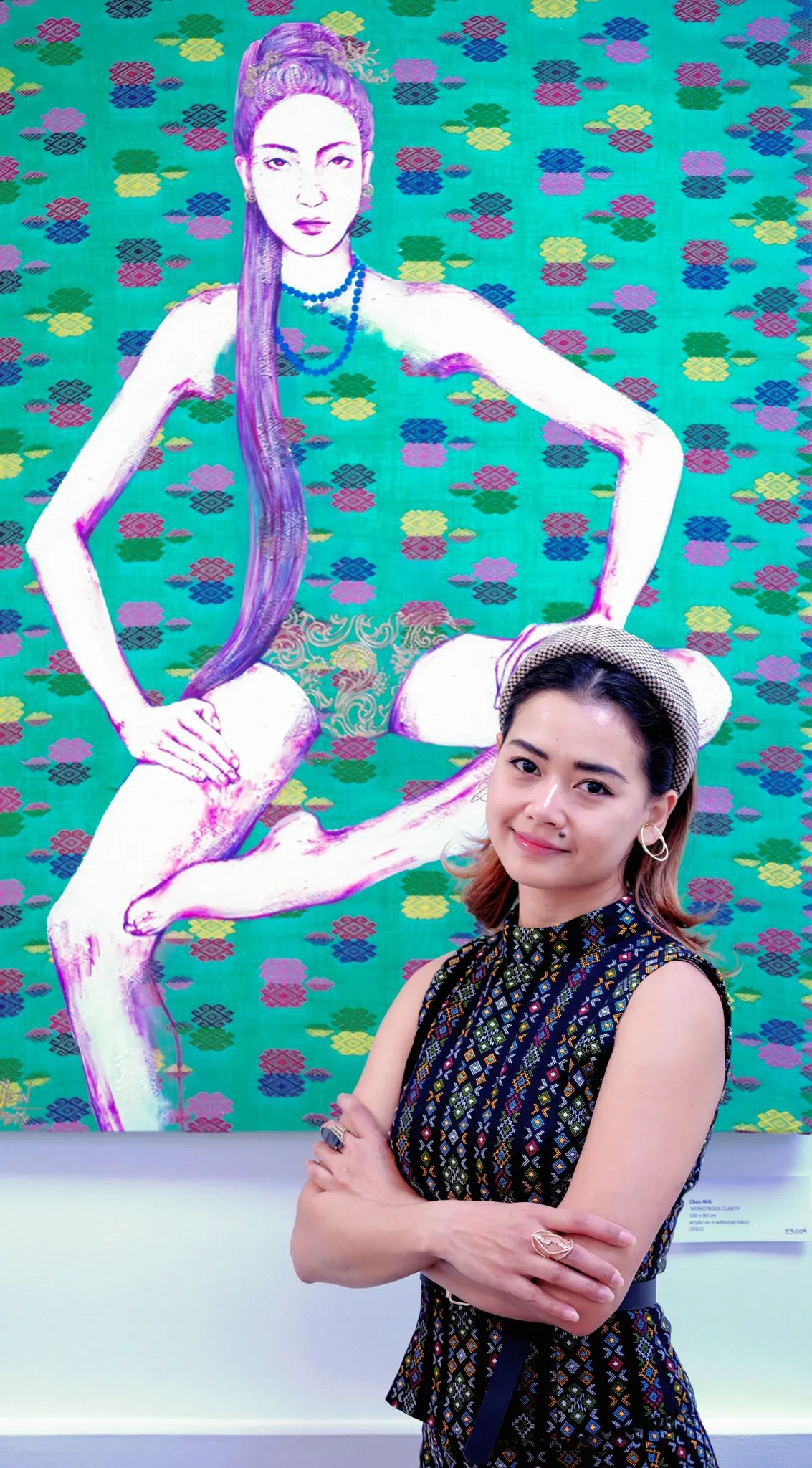

"The male audience would become really confused" - an interview with artist Chuu Wai

Billie Phillips: Chuu Wai, thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me. I’m such a fan of your work. To get us started, how would you describe your art?

Chuu Wai: My artwork is mostly focused on the situation of Myanmar women. Before the coup, I focused on themes of equality and the unsafe and unequal realities of women’s lives in Myanmar. I wanted to give the energy for women to speak out about our situation, to make changes, and to ask questions. But after the coup, the way I approached and created art slightly changed. Now, I have a lot of experiences from my life in exile (note: Chuu Wai now resides in Europe), from being away from family and my home – this has had an impact on my paintings. Now, I am still focused on women but from a different approach. It is more about the power of resisting and how we will build a better future for ourselves.

Also, it is to give information to those who do not know about Myanmar. Through my paintings, I am talking about what is happening there and giving the background – the links from the past, from history, from culture and literature. The hidden beauty as well.

BP: You started your work after experiencing sexual harassment on the streets of Mandalay - how did your work allow you to process that both individually and on a wider social scale?

CW: When this harassment happened to me and my sister, I thought we were just unlucky that it just happened to us in the early morning. After that moment I went to school and talked to people about it, and surprisingly they all had similar experiences. Some were so difficult to describe. I was so surprised – I had thought it just happened to us because we were unlucky, but it happened to all of us.

I think this moment opened my eyes, once I listened and when I asked more questions to the women and girls around me, I learnt that it happens at festivals, in crowds, and even on daily transportation on buses – even in Yangon. It happens in the countryside on motorcycles and bikes. I wanted to tell people, “The life we are living, we feel really unsafe.”

If we don’t talk about it, nobody will [know the scale of the problem]. This was the beginning of my series about women.

BP: Your paintings made in the post-coup environment have focused on women’s resistance - both on the frontlines and more privately. How do you see those unique facets of women’s resistance?

CW: At the beginning of the coup, my creativity was zero. I couldn’t create anything, I couldn’t process. But once I started, it felt more like illustrating the reality of what is happening. It is a process to understand what is happening to me, the people, and especially to women.

In the small cities, they think that women shouldn’t be involved in politics or be leaders – that fighting and politics is for men. It’s men’s problems. But still, there are a lot of women involved and a lot of iconic and strong powerful figures in the revolution are women. So, I started to be interested in the question – what happens if we win? Because I believe this movement is not only about changing the leaders of the country, it is also about what happens if we win over the military. What happens to the mindset the military put in us, using religion, culture and education to make sure the patriarchy is really strong?

If you ask people from Myanmar, “do you hate the military?” of course they will say “yes”, but sometimes the ideas they have [about women and culture] are from the military. It is inside them. Without realising it, they are accepting it. So, I think during this movement, this revolution, it is important to highlight these deep-seated concepts and propaganda messages given by the military. So, in my paintings, I put a question to the people, “Is this really what you think? Or did this come from somewhere else?”

BP: I hear that question coming through from your work. How do you see the contrast of women both as leaders and within the lens of social expectations to devote themselves to more traditional pursuits? And what does the word “traditional” even mean to you?

CW: When I was living in Myanmar, I would go back to the small town where I am from and I could really see the difference between the big city and the small towns. But now, I think this coup has shaken everything. Every situation. There are still conservatives in society, and I don’t blame them because I understand all the education and messaging we received was filtered through by the military, and what it told them about Buddhism. We know that sometimes the military collaborated with the monks, using Buddhism which is not real Buddhism. But they filtered their messages through monks because they know people wouldn’t question it. It’s worked really well. People believe deep down that males are higher than women, but that’s not really Buddhism. It’s not described like that by the Buddha, he never said “No women allowed”. It’s not real.

But now, it’s like weaving things together. Every thread, we do not know where it came from. [Women’s clothing] couldn’t be higher than men’s shoulders or it would be bad luck. A lot of people think that is Buddhist culture and that women are dirty, and their clothes should not be higher than men’s. But that’s not really from Buddhism, it is just from culture or tradition – it has come from other interests. But at the same time, some people are starting to realise what they believe is a strategy from someone or something else and someone put it in your brain. So, these people with the help of the internet and everything, starting to be open-minded, mostly young people, so they could see that what is right and what is not right. I think that with good education, and good messages, people will change their minds. This is not a instant revolution, I shouldn’t be rushing. I cannot say “in three years, in five years, everything will have changed.”

When I would go back to see my grandmother and my aunties, they would start to ask questions and I would show them slowly, but I think this will take time but it is really important. I hope that my art will help some people to think about these deeper questions.

BP: One of my personal favourite works of yours is the piece “Chew you up and spit you out” What are you communicating with the use of htamain* in that collage and what do you want people to reflect on?

CW: I use traditional fabrics, ethnic fabrics, with patterns from a long time ago. The idea I am communicating is by putting these fabrics higher up on the wall as artwork, higher than men. When I had an exhibition in Myanmar, often the male audience would become really confused. Should they look at it or not? Will it bring them bad luck, is it dirty? The reactions of the people were so interesting. But if you don’t know the history, these strong beliefs, you will just see the beauty of the fabric. But once you know the meaning behind the fabric, it's so interesting because when you Google “the frontline revolution of Myanmar” you see that clothes are hanging on the frontlines, and you wonder about the culture, what are the clothes doing on the frontlines? So, it is really connected with the revolution, the use of fabric is powerful. I am still describing the situation of women and women’s resistance.

What is happening right now has a lot of connections to the past, and I link to the coups in 1962 and 1988, and also the time of British colonisation, because we still have some problems that we are facing right now that also came from that time. I want to show the people the bridge between the present and the past.

BP: Do you think men in the resistance movement are also having a bit of a reckoning with women and women’s roles? Are you seeing shifts there?

CW: I think definitely. For this revolution, the younger generations, they are starting to see all the flaws from the past, from what we were told by the military. I believe the young generations really want change and to be equal. The only thing we need is good information and a good education. All of us inside, we are burning, we want to change. We have to solve these problems. We are going in the right direction but sometimes we can get lost, we just need a little help, guidance and education. For my artwork, I am not looking far away. I am inspired by the things we do every day, from the everyday acts in Myanmar.

BP: What has been your experience of showing your work in overseas galleries since the coup?

CW: Once I left Myanmar, I participated in a lot of different exhibitions. Some didn’t really care that I came from Myanmar specifically, they just wanted my art. But often I get requests that the art should describe Myanmar. Because I’m a refugee artist, people expect your art might be horrible, showing killing and burning houses.

In the beginning, I didn’t think about the creative part, I was just showing how I felt, which was sad about what I had seen [in Myanmar]. But organisations mostly want the kind of artwork that you can see without describing it, that it’s clear and obvious at first sight.

The colour and composition might be beautiful, but they want it to be clear. And I participated like this, but I felt that way was not giving messages, it wasn’t linking the past to the future. Sometimes I was really torn between, should I change myself to what people are asking from me, or should I just keep resisting and creating what I believe? But it is really difficult to live as an artist in Europe. But the way I create art is more discrete, more quiet – if you don’t know about Myanmar or the culture, to understand my work you might need to read about it a little bit. So at first I got rejected a lot from exhibitions, they refused and refused. I felt so worn down. Plus, feminism is so developed in Europe, the movement has already happened. So, my work is a little outdated there, it is not on trend. They are more interested in other topics, like war and conflict. But I hope I am filling this gap.

I am glad I have found a few people, like in London, Bangkok – they really believe in me and my artwork, they think it is really important to take another approach to what is happening in Myanmar.

*htamain: a traditional garment worn by women in Myanmar.