Enforceability of accountability mechanisms: a dialogue in Mindanao

Democratic accountability in service delivery

Citizens equate democracy with certain level of development, in particular, when public services are being delivered, as they represent the elements of entitlement that are needed by the people. If it only when these services such as security, education, water provision, and healthcare, among others are provided from a democratic perspective and taking into account the needs, opinions and concerns of all citizens, that they are delivered in an effective and inclusive way. In order to achieve such democratic approach, mechanisms of democratic accountability ought to be placed rightly in the provision of services so these can accurately adapt to the needs of those using them. Democratic accountability is the creation and implementation of democratic social and political mechanisms to hold public service delivery to account. It is the fundamental element to transform services into development.

Effective enforceability of accountability however remain to be a challenge, either these are not properly in place or weakly executed. In these cases, not only do the accountability structures suffer, but in many cases citizens’ regard for the rule of law decreases accordingly, since existing regulations can or will not be enforced properly.

A case in point is Mindanao, the second largest and southernmost island in the Philippines. Despite having vast natural resources, poorest provinces of the country are in Mindanao, in particular the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) due to decades-long conflict complicated with issues of governance, security and underdevelopment.

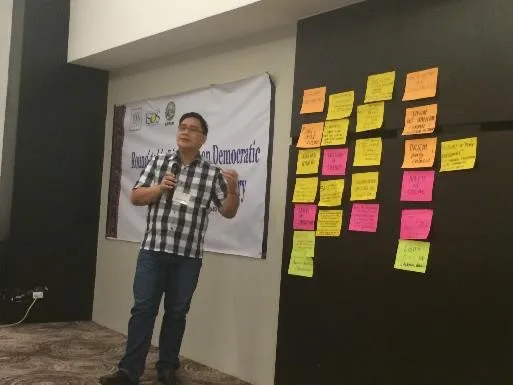

With these in mind, International IDEA in collaboration with the Alternate Forum for Research in Mindanao (AFRIM) and Institute for Strategic and Development Studies (ISDS) co-organised a roundtable discussion to provide a platform for key stakeholders discuss how enforceability mechanisms feature in the Philippines’ structure of accountability, what challenges they encounter, and to discuss and identify possible solutions to address issues in enforceability mechanisms given the local context. The roundtable also takes off from a relevant discussion paper published by IDEA on “Sanctions, Rewards and Learning: Enforcing democratic accountability in the delivery of health, education, and water, sanitation and hygiene”.

Around 25 experts representing the regional offices of the departments of social work, education and health were represented, the city planning office of Davao City, well-respected academicians from state and private universities, executives from ARMM agencies, a former member of the ARMM legislative assembly and leaders of indigenous peoples’ organisations attended the roundtable held in Davao City on 3-4 November 2016.

Challenges in accountability mechanisms

Formal structures are in place such as the freedom of information bill, procurement law where participation of eligible NGOs are encouraged, the open government portal to monitor local government performance and various sectoral watchdogs and advocacy platforms, among others. But in the context of Mindanao, there are plenty of challenges in enforceability of accountability mechanisms.

Participants at the roundtable stressed that delivery of services itself is difficult in conflict-afflicted areas, thus accountability mechanisms is much more challenging to e enforce. However, lack of capacity and resources to enable local governments to function properly, on top of corruption, are some issues that was identified as roadblocks. They also highlighted participation of civil society in democratic decision-making processes as a common issue, more pronounced in ARMM and among minority groups where a culture of silence becomes the norm amidst patronage politics and on-going conflicts.

Another interesting angle raised was accountability of private sector and aid agencies as duty bearers. As a developing country, the Philippines receive aid on continuous basis most especially for conflict-afflicted and disaster prone regions. Since the peace agreement in 1996, ARMM has been recipient of development aid to assist local communities with basic services - education, healthcare, livelihood – and support for post-conflict programs. Many however noted that accountability mechanisms for services delivered by private sector is lacking.

What can be done?

While accountability mechanisms are in place, there are yet still work to be done to ensure enforceability. Reward and sanctions as accountability mechanisms remain a challenge in current context; however, learning mechanisms may be of value such as inclusiveness in accountability given the plight of marginalised groups in the region of Mindanao. Another track way forward is to promote collaboration among various interest groups. A common road map for duty bearers and claim holders focused on building capacities of both local governments and community groups, strengthening accountability structures, and support for self-sustaining communities.