Elections need to be accessible for the ill during COVID-19 to avoid disenfranchisement

The right to vote in an election is one essential part of the democratic process. International standards on elections and democratic theorists attest that everyone should be equal before the ballot box. Democracy should be the greater leveler, irrespective of voters’ physical or mental health on polling day.

Disclaimer: Views expressed in this commentary are those of the authors. This commentary is independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

In practice, however, citizens often face different inequalities accessing elections, even in more normal circumstances. Citizens with disabilities might find barriers such as the absence of ramps at polling stations or being unable to travel on election day because of short- and long-term sickness. Measures to make elections more accessible for citizens with disabilities are therefore often prescribed in electoral law, such as remote voting, accessible polling stations, or the provision of braille ballot papers. Elections need inclusive voting practices in place to overcome these problems.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought these questions sharply to the forefront and presented an unprecedented challenge in delivering accessibility at the ballot box. The virus has led to the severe illness of many people around the world on their election day, with 40 million confirmed cases worldwide, and with the numbers rising fast. Millions more have been caring for family or friends or have been quarantined within their households if they or a family member has been infected.

The propensity of the virus to fall unevenly on populations means that it can fall unevenly on electoral participation. The virus does discriminate. It is thought to be more of a threat for citizens who have underlying health conditions, such as lung or heart disease, diabetes or conditions that affect their immune system—as well as those over 60. These citizens and their family members may therefore think more than twice about visiting a polling station in person. Elections involve the movement of millions of people on election day—elections staff, candidates and voters—and therefore are an opportunity for the disease to spread.

Inaccessible Elections and Disenfranchisement

There is a real risk quarantined (or other risk groups) will be disenfranchised. In some states, people diagnosed with COVID-19 are not allowed to vote due to restrictions on their freedom of movement as part of the government's regulations and laws to reduce the spread of infection (See Table 1). For example, the Prime Minister of Belize recently stated that people with COVID-19 or in isolation will not be allowed to vote during the General election on 11 November as it was against the law and that extending proxy voting for COVID-19 patients would not be possible. ‘ If you are COVID positive’ he said, ‘you are supposed to be in quarantine either at a government facility or at your own home.

Potential disfranchisement has been the cards elsewhere during the pandemic. In Singapore, citizens under a quarantine order, stay-home notices, or diagnosed with acute respiratory infection were not allowed to vote. This would have been a breach of Singapore’s Infectious Diseases Act if they had left their home. Similarly, in Taiwan, people under isolation or quarantine at home were prohibited from going and casting their vote as this would go against the Taiwan Communicable Disease Control Act. Meanwhile, in the Constitutional referendum in Chile on 25 October 2020, persons with COVID-19 will be sanctioned if they vote. Chile has reported 490,003 cases since March 2020. As of 7 October, 14,000 voters over the age of 18 will be disenfranchised as no special voting arrangements exist in the country.

The lack of special voting arrangements proved not only a danger to democracy, but unconstitutional in Croatia. The electoral management body was initially not planning to allow persons infected with the coronavirus to vote, stating that "more lenient measures would put citizens' health at risk. However, this decision was ultimately overruled by the Croatian Constitutional Court, which allowed COVID-19 positive voters to vote by proxy.

Enabling voting for citizens with COVID-19

The good news for democracy is that many of the 74 countries and territories that have held elections since late February 2020 have adopted new health and safety measures for voters and polling officials in collaboration with national health authorities. There are five main clusters of ways for enabling persons diagnosed with COVID-19 or under quarantine (see Table 1). These methods typically center around postal voting, proxy voting, home and institutionalized-based voting or arrangements in Polling station depending on what voting channels exist in the electoral law.

Table 1: Special Voting Arrangements used to facilitate voting for persons with COVID-19 or under quarantine by country

Alternative Voting Methods |

Countries |

Postal Voting |

Australia (Northern Territory), India (Karnatacka), Montenegro, USA,South Korea, Spain (Basque County and Galicia), |

Proxy Voting |

Croatia, Spain (Basque County and Galicia) |

Advance Voting |

Bermuda |

Home and Institutionalized-based voting |

Belarus, Czech Republic*, Lithuania, Italy, New Zealand, North Macedonia, Suriname* Israel* |

Arrangments in Polling stations |

Belarus, Czech Republic*, Jamaica, Malaysia (Sabah)*, India (Odisha), Italy, Sri Lanka*, South Korea, USA (Idaho) |

None of the above - persons with COVID-19 are restricted from voting |

Belize, Chile, Singapore, Taiwan (Kaohsiung) |

Source: Authors, constructed using International IDEA, media reports and EMB data.

Note: Countries included more than once in the table offered more than one method. Countries that have a star * offered voting methods to person under quarantine only.

Postal voting is one obvious mechanism. This was made available for people diagnosed with COVID-19 during the Parliamentary elections in South Korea in April. Alternatively, in June, ahead of the Parliamentary elections in North Macedonia, persons with COVID-19 or under quarantine could cast their votes from home via mobile voting teams accompanied by a doctor wearing personal protective equipment (PPE). In Spain, during the regional election in Galicia and Basque, voters with COVID-19 who were required to stay in isolation could either postal vote or proxy vote, but were forbidden from voting in person. In New Zealand, voters in quarantine or isolation could vote by telephone ahead of the 18 October General elections.

Some countries adopted arrangements in polling stations to accommodate in-person voting for people with COVID-19 or under quarantine. Citizens with mild cases of COVID-19 in South Korea could cast their ballot at one of eight "special early voting polling stations" established at care centres for COVID-19 patients across the country. Meanwhile, in Jamaica, citizens with COVID-19 could vote during on election day between 4 and 5 pm at polling stations provided that they notified their health ministry and that they wore a mask, gloves, protective shield and gown. They also needed to be accompanied by a driver who was also required to wear personal protective equipment. Early in the pandemic Israel established special medically supported polling stations with full PPE and screens for quarantined voters.

In Sri Lanka, people in quarantine were only allowed to vote at designated polling booths between 4 and 5 pm if they had received permission from health authorities and completed the first 14 days of the quarantine. In the end, this disenfranchised about 500 people who had not reached that requirement. This arrangement was implemented only after an unsuccessful attempt by the EMB to introduce advanced voting for people under quarantine as a new voting method. For the Senate Election in the Czech Republic on 2-3 October 2020, voters with severe medical conditions and persons ordered quarantined or isolated had several voting channels, which included drive-in voting (essentially, voters would vote from their car at specific polling stations), in-person voting at a special polling station or to vote from home by requesting a mobile polling team.

The ‘new normal’

COVID-19 is not going away soon. During the last month, several European countries have experienced a resurgence of COVID-19 as the number of confirmed cases globally increases at a rate of 230,000 – 400,000 cases per day between 20 September - and 20 October 2020. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the Head of the World Health Organisation, has said that he hopes that the COVID-19 Pandemic will be over in under two years. A leading manufacturer of one of the COVID-19 vaccines in development, meanwhile, has suggested that global inoculation will take until the end of 2024.

As a result, electoral commissions and administrators should take a long-term view of the COVID-19 Pandemic and how it may impact access to vulnerable groups and those with COVID-19 or under quarantine. New voting methods typically need to be agreed and legislated for between six months and one year before elections occur to uphold the principle of electoral law stability. Modifications to existing voting methods and arrangements in polling stations that facilitate access may be able to be done in a shorter period provided that they are deemed fair, safe and secure by all stakeholders.

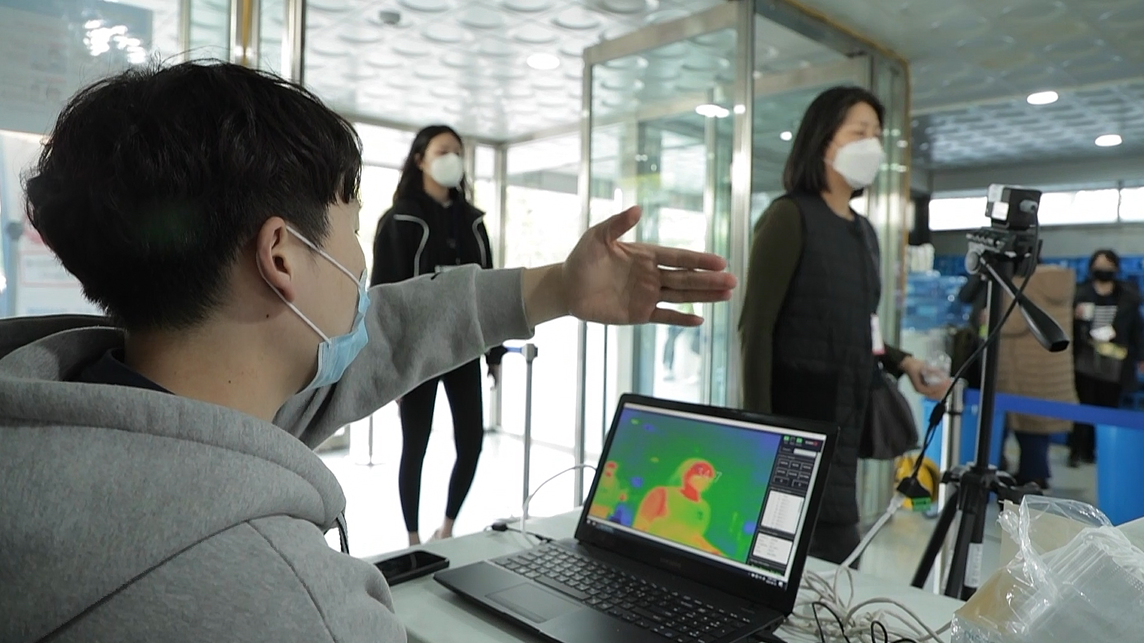

This therefore means introducing measures, not just for those citizens with COVID-19, but to stop the wider spread of the disease. Looking around the world, there are many practices that could be borrowed. These measures could include social distancing, access to hand sanitizers, disinfection of surfaces and voting materials, regular ventilation of facilities and access to masks, gloves and other personal protective equipment. New arrangements in polling stations that have been implemented by some countries also include temperature checks, one-way systems for entry and exit, extended voting hours, providing individual pencils or allowing voters to use their own, and limits to the number of people allowed to be inside the polling station. Temporary polling booths for voters identified with respiratory symptoms have also been an arrangement introduced in Malaysia, South Korea and Russia.

Many countries have scaled up special voting arrangements and encouraged citizens to vote early, remotely or through postal votes to reduce crowds on election day and lower infection risk. Some states have modified SVA to make it easier for citizens to vote. Notable examples include Russia, which extended advance voting and remote internet voting to around 1 million people during the constitutional referendum on 1 July 2020; Germany, which introduced 100% postal voting during a local election in Bavaria; and France which simplified proxy voting ahead of local elections in June 2020.

Just as steps are therefore needed to enable citizens with disabilities to vote, proactive steps are therefore needed to both ensure accessibility during the pandemic, and future-proof elections to ensure accessibility post-pandemic. For this to be possible, EMBs should continue working closely with health authorities and seek to learn from the process of doing so in order to ‘build back better’ and encourage greater accessibility in the conduct of elections under more normal circumstances. Buy-in from political parties for this will be essential.

Authors: Erik Asplund, Bor Stevense, Toby James and Alistair Clark

This Commentary was originally published by the London School of Economics (LSE) COVID-19 Blog on 23 October 2020.