Elections monitor: U.S. elections fall short of global standards

Disclaimer: Views expressed in this commentary are those of the authors, one of whom is a staff member of International IDEA. This commentary is independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

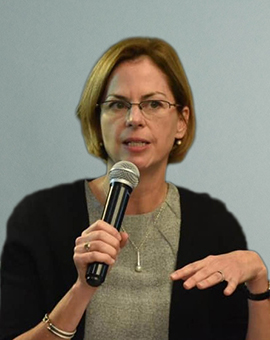

For more than two decades, I have lived overseas working for international democracy organizations, providing technical assistance and training to political parties, parliaments, civic advocacy groups, and, importantly, election observation and reform organizations. I have monitored more elections than I can count, from Gaza and Sri Lanka, to Cambodia, Indonesia and South Korea, and written numerous election reports of the electoral environment as well as recommendations for both reforms.

I am not accustomed to applying my election expertise and understanding of international best practice to my own country. But I think it is important that Americans step back and view democratic procedures through the lens of global standards. The U.S., along with other long-standing democracies, too often gets a pass and is not questioned despite the practices and controversies that we would condemn swiftly in less established democracies. So, I attempted to put on my international observer cap and write, as I have done in so many countries, a brief assessment of the U.S. ahead of the November election.

Electoral system: A good observation report puts elections in context by examining the system itself. Immediately, the U.S. runs into some serious democratic challenges. The Senate, for example, creates a vote power discrepancy of up to 1:7,000, whereby a voter in California has one seven thousandths of the representation as a voter in Wyoming. International standards stipulate that the size of voting districts should not differ by more than 10% to prevent such minority rule. If observed in another country, it would be a glaring red flag, particularly if power was so disproportionately handed to a dominant ethnic and religious group.

Gerrymandering: Of course there would also be a chapter on gerrymandering, where elected legislators draw the maps that get them elected. This conflict of interest ends up delivering inequities like Wisconsin, where Democrats won a majority of the vote but not a majority of the seats in 2018 state assembly elections. The electoral college would also deserve scrutiny, particularly given the origins of its establishment (a bargain to placate southern states by weighting their voting power) as well as the perverse incentive it has created today rendering only a handful of states worthy of any campaigning at the expense of the rest.

Election administration: There is no uniformity here, from how to register and ID requirements to the ability to use mail-in ballots. This can contribute to confusion and disinformation and makes it impossible to ascertain whether everyone had equal access to vote. Further, the world over, independent election commissions are considered a critical prerequisite for democratic elections. In the U.S., we hand over our elections to partisan bodies and elected secretaries of state. This approach has resulted in equally divided election management bodies between the two main political parties and a lack of a quorum due to the partisan nature of appointments. This "balance" creates deadlock and inability to act on matters such as campaign finance violations.

Read the full Op-Ed on Detroit Free Press