Elections and Covid-19: international electoral observation in 2020

Election Observation Missions (EOMs) have become an established part of the international electoral scene. Elections around the world have increasingly been observed, meaning that election observation has become widely accepted around the world and is commonly described as an international norm. It provides a way of collecting information about problems in the electoral process, such as election rigging and the denial of democratic rights.

Este artículo está disponible en español.

Disclaimer: Views expressed in this commentary are those of the authors. This commentary is independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

Election Observation—Election Observation Missions (EOMs)—have become integral to the electoral process across the world. International Election Observation provides the opportunity for countries to have their electoral processes assessed by ‘peers’ through their invitation to election observers, from national civil society organizations or the international community. EOMs collect identify shortcomings on an electoral process by assessing it against national legislation and international norms and standards on elections . They serves to hold incumbent governments to account for how they manage the electoral process and incertivise, but also through EOM Recommendations offer advice to deliver better elections.

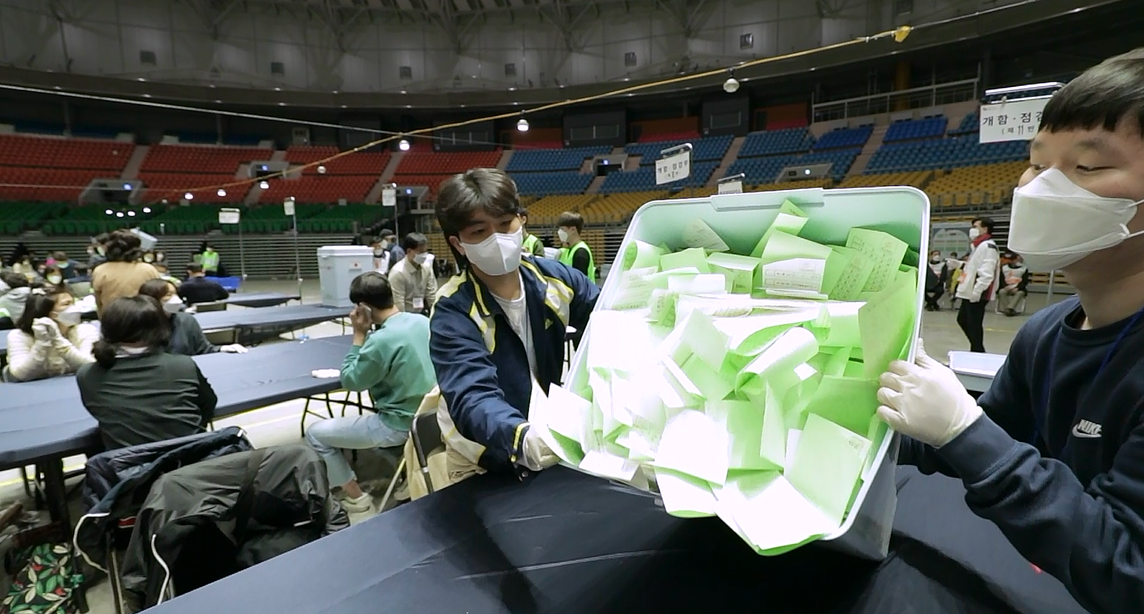

However, with movement strictly limited in 2020 because of Covid-19, EOMs faced unprecented challenges as a result of the pandemic. What challenges did EOM’s experience in 2020 in terms of deployment? Did EOMs cover health and safety measures as part of their methodology? How are EOMs adapting to Covid-19 restriction and what were some of the innovations? This article helps to address these questions by presenting information on international election observation in 2020. Data was collected from 38 EOM reports (both preliminary and final) on 28 countries that observed national elections between March and December 2020. This was the vast majority of EOMs that took place during the pandemic in 2020.

This analysis forms part of a series that has covered other parts of the electoral cycle, including campaign limitations, health and safety in polling stations and special voting arrangements. It forms part of an ongoing study between International IDEA and the Electoral Integrity Project on Covid-19 and elections.

Cancellation or Limitation? The Options for EOMs

The Covid-19 pandemic has posed challenges to traditional forms of EOM. A British Academy report in August 2020, which two of the present authors contributed to, suggested that EOMs effectively had four options open to them in responding to Covid-19. These were:

- Don’t observe;

- Observe traditionally;

- Observe with foreign nationals based in-country; and

- Observe virtually and through partnership

The benefits of not observing, were that this would remove any health risks, but at the cost of removing scrutiny of the electoral process. Observing traditionally provided scrutiny, and with little disruption to normal processes, although this also maximized health risks to observers, electoral staff and voters, while at the same time, not providing any innovation in observation. While the use of expat staff minimized costs and limited international transmission of Covid-19, this might mean a lower profile, level of expertise and effectiveness for the EOM. Observing virtually and in partnership could mean helping strengthen civil society groups while minimizing international transmission, although there could be little external control of observation methodologies. With most of these options, domestic travel to observe still had health and transmission risks attached.

Evidence can be found for several of these strategies. Given the apparent health risks to both the observers and citizens and officials they meet, many observation missions were generally unable to employ systematic and comprehensive election observation since international and domestic travel bans or other restrictions concerning movement were in place. In some cases, especially during the beginning of the pandemic planned EOM’s were completely canceled due to quarantine regulations for foreign visitors as well as increased costs.

The EU changed its approach by assessing on a case by case and as close to the date as possible whether a mission was to be deployed. The potential damage of not going was balanced against the safety of personnel and reputational risks. In 2020, the EU deployed four EOMs compared to thirteen in 2019 and fourteen in 2018. In Bolvia, the EU was not able to send a full-scale observation mission because of the risks of observers potentially getting Covid-19 or transmitting it, which would cause serious political impacts. Instead, the EU changed the format and sent a small expert mission for the capital only to assess the electoral process. The EU mission to observe the March general and regional election in Guyana was also cut short by 11 days as personnel had to be evacuated due to the pandemic.

Many of the EOMs, reduced both in number and in size, that went ahead visited a limited number of polling stations across the country or solely focused on their capital. Deploying observers to different locations and not only concentrating them in the capital city, is important to ensure there is a balance of coverage of different regions. In the cases of Croatia, Serbia and Romania, the missions merely focused on the capital, whereas the missions in Moldova, North Macedonia, Poland, Montenegro, Georgia, and Kyrgyzstan only visited a limited number of polling stations.

Due to the coronavirus pandemic, ANFREL could not conduct a fully-fledged election observation during elections in Sri Lanka. The EOM had to downsize its mission and deployed observers had to go through 14-day quarantine. It also had travel challenges due to the absence of flights. ANFREL also had to conduct an assessment of the Sri Lankan elections through remote interviews with experts and local volunteers.

In Trinidad and Tobago, ahead of the 10 August 2020 General election, neither the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) nor the Commonwealth of Nations were able to send EOMs as they faced financial constraints in paying for the cost of the 14-day quarantine period required for foreign visitors. Quarantine restrictions also hindered the Commonwealth from deploying an EOM in Staint Kitts and Nevis during the June 2020 general elections, however, CARICOM deployed a team of three observers who were tested on arrival for Covid-19 two days before the elections.

Are EOMs adapting to the Covid-19 restrictions?

Some EOMs have adopted more innovative strategies in response to the pandemic and instead chose to operate virtually and to collaborate more with domestic observers. In Myanmar, the Carter Center's observation mission deployed several core team experts that were working remotely while engaging closely with Myanmar nationals serving as long-term observers. In Malawi's presidential rerun, the Commonwealth Secretariat utilized virtual monitoring by partnering with local organizations that were able to collect data. For the elections in Tanzania and Seychelles, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) organized virtual consultations rather than deploying an EOM. Moreover, the SADC also developed guidelines for election observation under public health emergencies.

Many countries that held elections in 2020 introduced restrictions on campaigns as well as health and saftey measures. The compliance to these measures by stakeholders and to some extent enforcement was monitored by most EOMs as part of their observation methodology. However, there were some EOMs in 2020 that did not report on Covid-19 (See Table 1).

Table 1. International Election Observation Missions reports by country

Source: Authors, constructed using EOM preliminary and final reports.

Conclusion

While many EOMs have been cancelled, the pandemic is also providing an incentive, albeit from necessity, for EOMs to accelerate innovations in methodology and approaches to their mission. Where this involves links with domestic organizations, this may help encourage and build capacity among civil society organizations to monitor elections. Where this has involved remote or virtual means, these may well be pushing new boundaries in what might be achievable with EOMs. There are obvious dangers with both these potential developments. These include becoming overly associated with particular civil society interests at the exclusion of other sides in a country’s politics. There is also the question of blurring lines between the purpose and objectives of IEOMs and citizen observers that collaborate. Or alternatively, relying too much on technology, where human and context specific interactions may provide better oversight. Nonetheless, with EOMs, as with other aspects of electoral, political and socio-economic processes, the pandemic promises to be a source of both extreme challenge and future innovation.

|

Main Findings on international election observation missions

|