The elections organised on Africa’s Super Sunday a week ago have put the current status of democracy on full display. In Benin and Cape Verde, fierce electoral campaigns by political parties and candidates led to leadership turnover in the presidential office and national assembly, respectively. In Congo, Niger and Zanzibar, on the other hand, election day on 20 March tells the story of more reluctant marches toward democratic transition–if not departures from the democracy path.

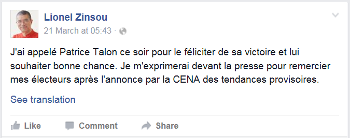

The presidential elections in Benin have re-affirmed the country’s steady course towards the consolidation of democratic institutions and structures. In the run-off presidential contest, where approximately 65 per cent of the voters turned out to cast their votes, businessman Patrice Talon beat the prime minister and incumbent party’s nominee Lionel Zinsou to the post. While the two candidates assembled almost equal support in the first round, Talon eventually won by a landslide. The day after the polls closed and already before any provisional results had been released, Zinsou conceded defeat–via his Facebook page–and thereby paved the way for the fourth peaceful leadership transition in the country’s multiparty history.

In a recently published report by the Electoral Integrity Project, the perceptions of integrity in Benin’s elections ranks highest among electoral processes in Africa, during the period 2012-2015. The report also ranks Benin’s elections above processes undertaken in countries including Ghana, Namibia and South Africa. The Autonomous National Electoral Commission (CENA), which is responsible for managing the electoral process is playing a key role. Having been praised for its impartiality and its capability in delivering credible elections, the CENA has contributed to building trust among contestants in processes and outcomes of the elections as well as to deepening democratic electoral practices more generally.

In Cape Verde, the Movement for Democracy (Movimento para Democracia, MpD) won a majority of the seats in the parliament after having spent 15 years in opposition. Cape Verdeans were seen to punish the African Party for the Independence of Cape Verde (Partido Africano da Independência de Cabo Verde, PAICV) for increasing the public debt and for not being capable of reducing youth unemployment. The country, comprising of nine volcanic islands off the Senegalese coast, will embark on presidential elections later this year. Notably, the PAICV lost the presidential seat to the MpD in 2011. Whether the voters will give MpD full support or opt for co-habitation remains to be seen.

…three steps back…

In the Republic of Congo, incumbent President Denis Sassou Nguesso has as many predicted taken up a third term in office. With the preliminary results standing at 67 per cent in favour of his continued rule, a second round will not be necessary. The re-election of the 72-year-old former colonel was preceded by the 2015 constitutional referendum that not only saw the removal of the two-term limit but also the 70-year age limit to the presidency. Nguesso thereby joins a growing group of presidents such as Cameroon’s Paul Biya, Burundi’s Nkurunziza – and proposedly also to be joined by Rwanda’s Kagame later this year.

The 20 March elections in the Republic of Congo were marked by the shut-down of Internet, phone and SMS-services–allegedly to prevent illegal publication of election results. The international community called on authorities to restore communication facilities, but the media restrictions were nonetheless prolonged far beyond the initially stated 48 hours. Notably, this is the second time in only one month that authorities have resorted to media tampering during elections: on 20 February, the Uganda Communications Commission blocked citizen access to social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter and Whatsapp as well as money transfer services. Considerations around national security and vote buying were cited as reasons for the social media crackdown.

In Niger, the incumbent president Mahamadou Issoufou captured more than 92 per cent of the vote. While the political party supporting the runner-up candidate boycotted the second round of the election, its candidate from the first round, Hama Amadou, who was imprisoned on baby-trafficking charges and flown out of the country for medical treatment a few days earlier, chose to take part in the run-off. For obvious reasons, the opportunity for the opposition to run an effective electoral campaign was limited.

Struggling with jihadists in the north and with Boko Haram insurgents in the south as well as sustained poverty (Niger currently ranks last on UNDP’s Human Development Index) calls for Niger to establish a strong, capable and action-oriented government. Low turnout in the second round of the elections, however, suggests that Issoufou might not have the support base required to push an effective security and development agenda. In a statement made on Wednesday, 23 March, Issoufou expressed his readiness to “put in place a government of national unity with the opposition in order to face the threats facing the people of Niger”. In the face of the recent controversial elections, the establishment of an inclusive government coalition might be a way to reduce inter-party bickering and put the focus back on the important work ahead.

The re-run of the Zanzibar elections did not offer a good starting point: claiming that they won the elections organised back in October that were declared null and void by the chief of the Zanzibar Electoral Commission, the Civic United Front (CUF) decided to boycott the election altogether. As a result, incumbent President Ali Mohamed Shein won on the Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) ticket. However, the challenges to Shein’s continued leadership are not over. According to The Citizen on 23 March, "there is no way the CCM will be able to run the country effectively and to the satisfaction of all, without some involvement of the CUF. The CCM might have won the election legally but that doesn't automatically mean it has wholesome credibility and legitimacy to rule alone.” Acknowledging that the elections were marred by low turnout and that the CUF holds considerable political support, power-sharing arrangements may be necessary to bestow legitimacy on the incoming government on the semi-autonomous isles.

…and constitutional referendum with a twist!

Presidential term limits have been high on the constitutional referenda agenda in Africa with presidents seeking to extend their time in office. In the case of Senegal, however, the 20 March referendum aimed to shave two years off the seven-year presidential term in line with President Macky Sall’s election promise of 2012. The “yes” movement took the referendum with 63 per cent voting in favour. Notwithstanding intense mobilization efforts, the turnout at only 40 per cent was disappointing in a referendum also considered to represent a measure of Sall’s popularity.

Two developments worth watching

The African election year has only started. In the coming months, we are expected to see presidential elections taking place in Djibouti, Sao Tome and Principe, Equatorial Guinea and the Gambia. General elections in Ghana and Zambia, two countries that have been steadily moving forward on the democratic path, are also happening this year. Based on the elections organized throughout the continent so far, let us keep in mind two developments when watching the coming elections:

- Will authorities keep their hands off free media and allow journalists and citizens alike to operate and communicate with one another freely on the internet? With growing internet penetration on the African continent as well as an increasing crowd of social media savvy and politically restless youth, information sharing and general citizen engagement on elections-related matters is bound to proliferate. Authorities and electoral management bodies must obey with international obligations and best practices and allow citizens the right to express their views on politics and elections—whether positive and negative.

- Will opposition candidates accept defeat when warranted? In Benin, Zinsou conceded defeat before provisional election results were released. This was a welcoming gesture on a continent where defeated candidates have a tendency to reject the election results. Notably, elections can be marred by irregularities and opposition parties and candidates have the right to seek redress through the legal systems in place. But all the same, when defeat is warranted, candidates must accept the results in order for politics – and development – to keep moving on.