This Sunday, 25 October, Chile will define if they want (or not) a new Constitution and through what mechanism. This could lead to an unprecedented process in the history of the country, allowing citizens to choose the representatives in charge of drafting and preparing a new constitutional proposal.

Disclaimer: Views expressed in this commentary are those of the author. This commentary is independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

Este artículo está disponible en español.

Background

On 18 October 2019, Chile experienced a major social upheaval in response to unsatisfied social demands and historical inequalities, compounded by a widespread perception of discontent provoked by shortcomings in the main aspects of development and social services such as health, education, social benefits, and the pension systems. It also reflected the lack of consensus around the ethical and social values incorporated in the current Constitution, which was adopted during the dictatorship in 1980. After weeks of disorder, violence, and political confrontation—which also had negative economic effects—on 15 November 2019 an agreement was reached (in the “Agreement for Social Peace and the New Constitution,” which brought together 10 political parties) to hold a constitutional referendum, originally scheduled for 26 April 2020. As with other elections in Latin America and worldwide, the referendum had to be postponed—to 25 October—due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Importance of this plebiscite

The national plebiscite to be held on 25 October 2020, will enable the citizens to determine whether they wish to have a new constitution, and if so by what mechanism, making it possible to resolve the issues concerning the legitimacy of origin of the current Constitution of Chile. Accordingly, this referendum sets the stage for an unprecedented process in the history of Chile in which the citizenry may subsequently choose the representatives to draft a proposed Constitution, unlike what happened with earlier constitutions.

What is being voted on?

The 25 October national plebiscite will enable each voter to approve or reject the proposal to draft a new constitution, in addition to the body that should draft it: Should it be a "Mixed Constitutional Convention", made up in equal parts of members elected by popular vote and current legislators? Or a "Constitutional Convention" made up exclusively of representatives elected by popular vote?

In the event that the "I approve" option receives a majority of votes, the president must convene an election to choose members of a constitutional convention on 11 April 2021, at the same time as elections are to be held for mayors, local council members, and governors.

If the option of "Constitutional Convention" wins then 155 citizens will be elected, from the electoral districts established for the election of national legislators. If this option is chosen, 50 per cent of the members of the new Constitutional Convention would be women; this would make it the first body in the world to draft a national constitution with full gender parity. Law 21,216, promulgated in March of this year, determined that the popular election of constitutional convention members would be governed by a parity requirement both in the lists of candidates and in the final results.

If the option of "Mixed Constitutional Convention" wins, it would be made up of 172 members, with 86 legislators elected by the Congress, and 86 citizens elected by popular vote. In that case, gender parity would only apply to the seats chosen by popular vote.

Once chosen, the body in charge should draft and adopt a proposed text for a new constitution within nine months; this deadline may be extended, one time only, for an additional three months. According to how it was defined in the Agreement for Social Peace and the New Constitution, the constitutional body should adopt the rules and regulations for a vote to require a quorum of two-thirds of the members.

A plebiscite to ratify the new constitution it, with compulsory voting, must be held 60 days after publication in the Official Registry (Diario Oficial) of the Supreme Decree that sets the plebiscite. If the new proposed constitution is confirmed, the President of the Republic is to promulgate the new Constitution of the Republic.

How is voting conducted?

Voters receive two ballots. The first contains the question: "Do you want a New Constitution?”, followed by two horizontal lines, alongside one another, with the response "I approve" or "I reject" The second will contain the question: “What type of body should draft the New Constitution?" followed by the responses: “Mixed Constitutional Convention” and “Constitutional Convention,” both alongside their respective definition.

In Chile, the legislation provides only for in-person voting. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, and in light of what has been determined by the respective health protocol, voting with graphite pencils has been changed, making it possible for the first time to vote using a pen with blue ink.

Voting in Chile has been voluntary since 31 January 2012, pursuant to Law 20,568. Accordingly, all persons who meet the requirements for voting are automatically entered in the voter rolls. In the case of the plebiscite for ratification (or rejection), contemplated for 2022, the vote will be obligatory.

In addition, Chilean legislation provides that Chileans 18 years and over who meet the requirements set out in the law may vote abroad, and are authorized to vote from their countries of residence in national plebiscites, presidential primaries, and presidential elections.

Citizen perceptions

Citizens’ perceptions of the plebiscite (and the social upheaval that led to it) are mixed. According to the latest results of the Pulso Ciudadano survey (Activa, published 19 October 2020), 55.7 per cent of the persons interviewed stated that as a result of the social upheaval “the citizenry has been heard from more," 52.5 per cent remarked on “the holding of a plebiscite to decide on a new Constitution," while 38.4 per cent indicated that it produced an “economic recession, loss of jobs” while 35.2 per cent identified “greater uncertainty and instability in the country” as a consequence. According to the same report, 61.7 per cent noted that the social upheaval was positive for the country, whereas 26.3 per cent said it was negative.

Image credit: Activa (October 19, 2020).

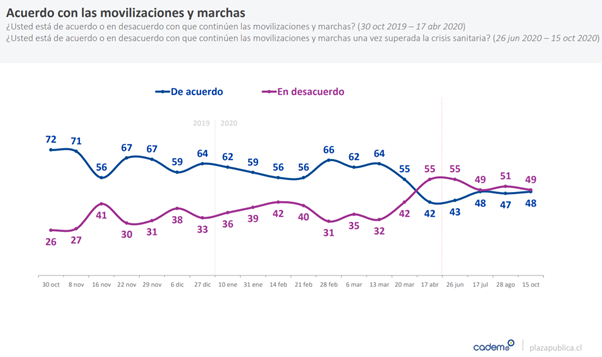

According to the latest results of the CADEM survey (published 19 October 2020), some 40 per cent say that "an economic plan to spark recovery in Chile” is the most pressing issue to move towards normalization, while 37 per cent noted “going forward in the process of the new Constitution” as the top priority. At the same time, 49 per cent of those surveyed said they disagree with “continuing the mobilizations and marches once the health crisis has been overcome,” compared to 48 per cent who agreed with continuing them.

Image credit: CADEM (October 19, 2020).

What the latest polls say

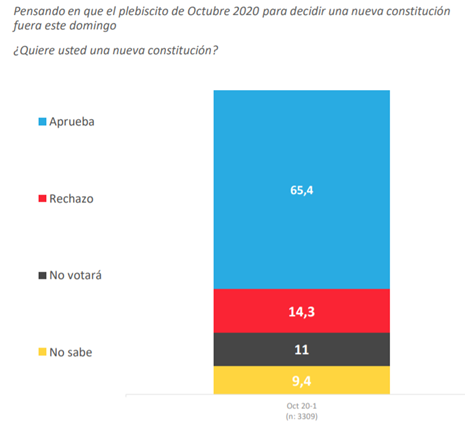

Two weeks out from the national plebiscite the special study by Pulso Ciudadano (Activa, published 10 October 2020) indicates that 65.4 per cent would vote “I approve,” 14.4 per cent would vote "I reject," 11 per cent say they will not vote, and 9.4 per cent say that they don’t know. As for the second ballot, 56.2 per cent of those surveyed noted that they will vote for the “Constitutional Convention,” 20.1 per cent for the “Mixed Constitutional Convention,” 13 per cent indicated that they will not vote, and 10.7 per cent have yet to decide their preference.

Image credit: Activa (October 10, 2020)

Regarding participation, 72.6 per cent indicated that they are certain they will go to vote in the plebiscite on 25 October, whereas 15.5 per cent indicated they are certain that they will not vote. Accordingly, Activa estimates the participation of about 55 per cent of registered voters, i.e. approximately 8.7 million. This is a great unknown in times of pandemic, considering that electoral participation of Chileans in the 2013 and 2017 general elections—elections in which voting was voluntary and registration automatic—ranged from 40 per cent to 50 per cent.

Final comments

The national plebiscite of 25 October 2020 represents a historic opportunity for Chilean democracy: Will Chilean citizens work out their differences through this election? Or will disagreement and discord among all the political and social stakeholders remain? Deciding this will be up to every man and woman who lives in Chile. Moreover, is the Chilean export-oriented, free-market model in danger? Will a new constitution be the best path towards broader democratic representation and social equality? What are the risks and consequences for Latin America on seeing that one of the most stable economic and political models in the region is being called into question as demands are made for change?

Source: Regional Office. International IDEA's Latin America and the Caribbean Programme.

References