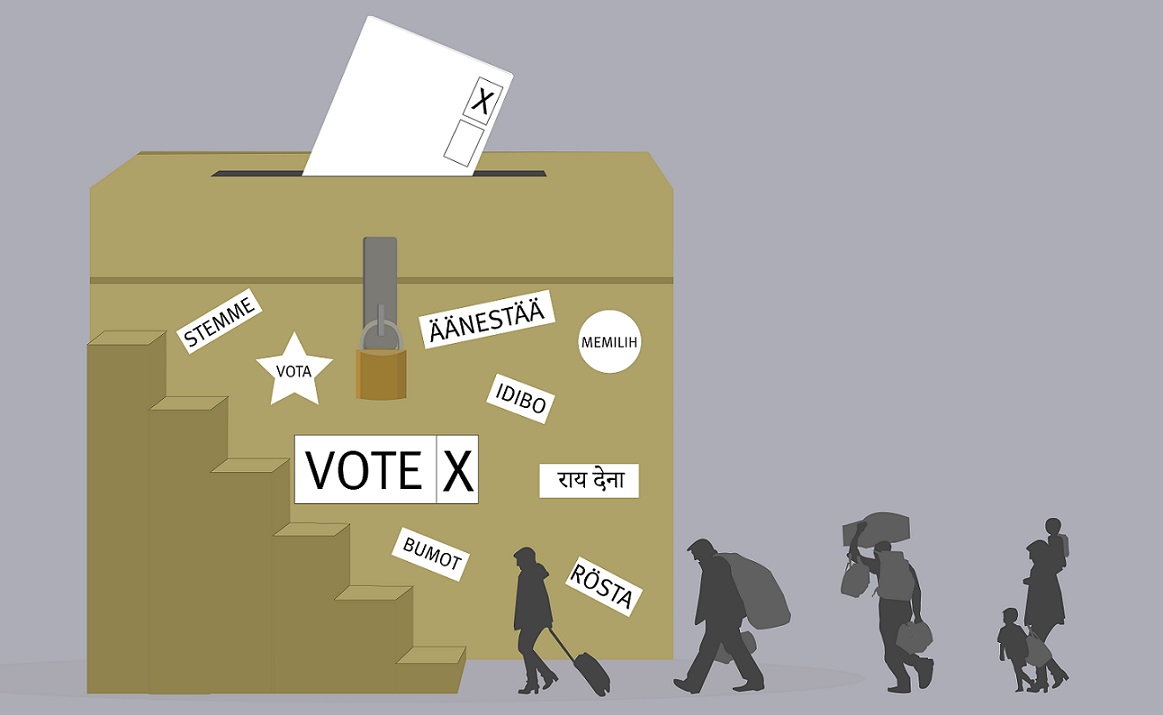

Political rights for refugees are an endurance test for the fabric of democracy

Political rights of refugees are an endurance test for the fabric of democracy. The recent migration waves resulting from civil wars have brought the debate on this topic back on the public agenda. Governments, political parties and other actors throw their weight behind various public policies which are geared towards regulating illegal migration.

The topic of migration and of refugees and asylum seekers comes up constantly in election campaigns, thus easily becoming a populist card with which politicians may strive to attract votes. Resolving the “migration crisis” can become a panacea for most socio-economic ills facing a country. However, not only does this rhetoric miss the mark on the real causes of such ills, but also risks overlooking other dimensions of migration, such as for example the political participation (both formal and informal) of migrants in host or origin countries. Their rights to political expression are simply not a priority in public fora. This in return can exacerbate the marginalization of refugees, leaving them without voice in their host countries, which is counter-intuitive to democratic values.

Depriving refugees of their democratic rights deprives a whole society from fully exercising its democratic potential. The public debate on refugees revolves normally around issues of their immediate humanitarian and security concerns, or on challenges that have a direct and imminent impact on their livelihoods. The debate might also stretch to discuss legal perimeters of their circumstances, such as whether they should be legally allowed to reside in a host country or be returned home. This debate, however, does not generally dwell on issues of political engagement of refugees. Granted, security and humanitarian concerns may be of acute relevance for refugees, but it is also important that we explore ways for them to be able to voice their political concerns, either through formal or informal participation channels.

On 19 April 2018, International IDEA with the support of Robert Bosch Foundation launched a new report titled Political Participation of Refugees: Bridging the Gaps. The report explores the main challenges and opportunities related to the political engagement of refugees in host and origin countries. Among formal mechanisms of engagement in host countries, the report examines issues of citizenship and naturalization, access to electoral rights and political parties. It also looks at issues such as out-of-country voting (OCV) which enables the refugees to stay politically engaged in their origin countries. Moreover, in the absence of formal means of participation, refugees often engage in politics through non-formal ways. Hence the report also examines the refugees’ involvement with civil society and grassroots initiatives, an area often referred to as the transnational space of political activism.

The launch, which took place in Berlin, attracted a wide interest from refugee advocacy and civil society organizations, academia and regional organizations. The debate was particularly focused around the case studies of Germany, Sweden and the UK, with panelists sharing their own experience either as refugees or as persons working on refugee matters. Germany, for instance, is a case in point where some of its states have established consultative bodies which are meant to advocate for the interests of refugees at the local level. In so doing, these states are enacting the Council of Europe’s 1992 Convention on the Participation of Foreigners in Public Life at Local Level. Article 5 of this Convention provides that contracting states should ‘encourage and facilitate the establishment of consultative bodies or the making of other appropriate institutional arrangements for the representation of foreign residents by local authorities in whose area there is a significant number of foreign residents’ (Ibid.).

The second launch took place in Kampala, Uganda on 25 and 26 April 2018, where the focus was more on the case studies of Kenya, South Africa and Uganda. These cases have generally shown that the road for a refugee to obtain naturalization in the host country is extremely difficult, if not impossible. For as long as naturalization remains a precondition for the right to vote, refugees cannot exercise that right at any point of their stay in the host country. However, Uganda for instance has made marked progress in establishing so-called Refugee Welfare Committees, which are meant to serve as liaisons between the Office of the Prime Minister, service delivery partners and refugee communities.

International IDEA is in the process of presenting the report’s findings in other venues, such as in Tunis (10 May 2018), New York (17 May 2018), Brussels (24 May 2018), Stockholm (31 May and 12 June 2018). Based on the launches held so far, this is an issue that calls for an all-encompassing and honest debate between all stakeholders involved. One of the underpinning issues that transpires from the report’s findings and the launches is that naturalization and citizenship is almost always a prerequisite for the refugees to have a right to vote. If one does not have citizenship, one will likely not be in a position to cast a vote, irrespective of how long they have been residing in the host country. Such is the case, for instance, with Syrian refugees living in Lebanon or Turkey, or refugees from South Sudan and Somalia residing in Kenya.

Out of the eight countries analyzed, only Sweden makes an exception by allowing non-citizen refugees with three or more years of uninterrupted residence to vote in local elections. Furthermore, the practices and the laws that regulate OCV vary to a great degree depending on the country context. Countries of origin such as Afghanistan have a legal framework in place for OCV. Indeed, in its first democratic elections in 2004, Afghanistan made serious efforts in reaching out to Afghan refugees living in neighboring Iran and Pakistan. Such efforts, however, were hampered in more recent elections in 2009 and 2014. Other countries with large refugee communities abroad often do not make efforts to accommodate voting for them, or do not have a legal framework in place. The reasons are manifold: they may be political or ideological or may simply be financial and logistical.

As the report recommends, each host country can do more to facilitate a swift and realistic naturalization of refugees. Ensuring a fair naturalization and citizenship process for refugees who have been granted permanent status lifts them out of a legal no man’s land in respect of their voting rights. It is a durable solution for refugees and a precondition to ensure greater political engagement. Secondly, countries of origin need to reach out to their diaspora communities and offer them opportunities for OCV. If such opportunities are not possible, both host and origin countries have numerous innovative ways to reach out to refugee communities through non-conventional means of engagement, such as social media platforms and transnational activism.

More democratic rights for refugees are not just for refugees. Such rights also have to do with the kind of political system that is in place and its degree or inclusion and representation. Greater political inclusion of refugees means a better quality democracy for all.