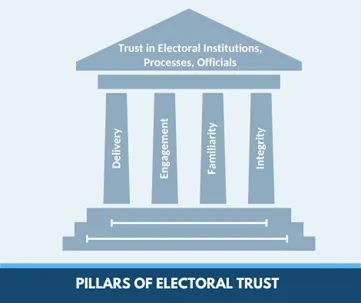

Pillars of Trust in Elections

“Building trust is very difficult and takes time, while losing trust is brutally simple and often fatal” – Bill Gray,former Electoral Commissioner, AEC

Electoral trust is at stake and it matters. High-profile elections in which process and results were questioned, such as Kenya, Venezuela, Myanmar and the United States, alongside day-to-day experiences of electoral management bodies (EMBs) worldwide, are fueling a sense of urgency to find answers to one question: ‘How can we build, maintain or rebuild trust in elections?’

In recent decades, the building or maintaining of trust in electoral management has been most challenging when

- Creating an EMB ‘from scratch’ in transitions to democracy and imbuing that institution with the capacity and legitimacy to deliver credible elections and accepted results;

- Implementing significant electoral reforms such as expanding special voting arrangements, introducing new voting technologies, voter registration or identification systems, or redesigning electoral systems;

- Protecting EMB independence and credibility in the context of backsliding democracies, either from systemic and structural dismantling or from discrediting of electoral processes for short-sighted political purposes;

- Protecting electoral processes from malign, often foreign interference and disinformation designed to disrupt or sow doubt.

Electoral trust reinforces belief in democratic institutions and underpins the acceptance of the election results that enable democratic and stable transitions of power.

Trust-building solutions are relevant directly to EMBs, but can also influence long-term changes in the design and policy of electoral support and infrastructure.

Trust in electoral officials, institutions, and processes can be informed by insights into the relations between citizens and state institutions in other sectors. For example, under what conditions do people willingly pay taxes, accept court decisions, or follow guidelines from public health authorities? Studies from these sectors show that delivery, ethical behaviour, stakeholder engagement and reliability are essential to promote public cooperation, compliance and confidence (Coglianese 2016[1], Drahos 2017[2]). With this article—anchored in PhD research on electoral trust and adapted and tested in a series of public for a—we apply these trust-building elements to electoral institutions.

Several factors differentiate trust in elections from other public sectors. High stakes affect confidence because of the potential for the short-term interest of political actors to discredit elections or because close results make scrutiny for potential mistakes in the voting or counting particularly rigorous. The severe time limitations and complex logistics of elections make such errors inevitable. Temporary polling workers—nationwide and on a single day—are working long days with unfamiliar new technology or procedures and the widest diversity of citizens as clients. The stress of this time-bound, high-stakes environment makes trust particularly complex for electoral management bodies.

Unpacking this trust complexity demands the ability to look at institutions, processes and officials from multiple angles. The four pillars of electoral trust listed below can help structure conversations around EMB trustworthiness.

Pillar 1: Trust of Delivery

Trust of delivery is rooted in demonstrating that the EMB has the resources, competence and capacity to deliver an election that meets stakeholder needs and legal requirements. Voters and stakeholders will be reluctant to trust an EMB that is not seen as competent to deliver in future or has failed to deliver in past elections. Similar concerns may arise if EMBs are percieved as not having a complete understanding and oversight of systems in use, which may be the case after significant changes in the electoral setup or the increasing digitalization of elections.

Trust of delivery is rooted in demonstrating that the EMB has the resources, competence and capacity to deliver an election that meets stakeholder needs and legal requirements. Voters and stakeholders will be reluctant to trust an EMB that is not seen as competent to deliver in future or has failed to deliver in past elections. Similar concerns may arise if EMBs are percieved as not having a complete understanding and oversight of systems in use, which may be the case after significant changes in the electoral setup or the increasing digitalization of elections.

Trust of delivery is typically put at risk in situations where the EMB is not issued with sufficient resources for delivering elections, where electoral reforms are legislated without allowing for the required timeframes, and in cases of shortcomings in training and professional development.

Pillar 2: Trust of Engagement

Trust of engagement is rooted in community building, disclosure, and communication. Disclosure requires developing an institutional culture of openness and accessibility, including ensuring that key steps of the electoral process are transparent and verifiable.

Community building entails inclusive, proactive, and strategic communication and information-sharing with stakeholders, including parties, candidates, civil society, domestic and international election observers, and citizens.

Trust of engagement is the most reciprocal of all four pillars and involves a give and take between the EMB and other stakeholders and an understanding of the posture they take: are they committed, doubtful, game playing or spoilers?

Establishing trust of engagement can avoid distrust before it occurs and foster a network of potential allies should the EMB come under unjustified attack. Improving engagement trust may require significant changes for the EMB, such as cultural shifts and strengthened communication modalities.

Pillar 3: Trust of Familiarity

People trust what they know; the trust of familiarity is premised on continuity and predictability. This aversion to change has profound implications for electoral reform and digitalization-related expectations of disruptive change. Parties and candidates naturally distrust changes which may impact their chances of success.

Electoral reform is sometimes necessary and unavoidable. EMBs have to be aware and consider that such reforms disturb the system trust based on familiarity. Strategies to mitigate concerns or fear of change can include strengthening backup systems, not leaving stakeholders in the dark, increasing communication about upcoming changes and providing all information and details about developments as soon as they become available. There must also not be a doubt that the EMB can deliver the necessary change.

But this may, in some cases, not be enough. Some changes, such as introducing new special voting arrangements, may take several electoral cycles to be adequately understood and predictable. As far as possible, significant changes to the electoral process should be implemented in gradual steps and spread out over multiple electoral cycles, controlling the speed of innovation to avoid disruptions.

Pillar 4: Trust of Integrity

The first three pillars are transactional and can be built incrementally. Trust in integrity is fundamentally different and rooted in the ethics and character projected by the EMB. This trust can partially be built by the EMB through its conduct; by demonstrating adherence to ethical behaviour in the conduct of work, embodying and displaying ethical values and by fair and inclusive dealings with all parties, candidates and voters.

Trust of integrity depends greatly on the democratic setup in which the EMB is embedded. In contexts with severe democratic deficits, it must also be expected the EMB will struggle, maybe find it impossible, to gain the trust of integrity that may be absent in other institutions.

Ultimately, the trust of integrity is related to the formal and practical independence of the EMB, and whether the electoral institution perceived as a legitimate and impartial defender of electoral democracy.

Rebuilding trust pillar by pillar

As elections are under threat, there is a need to create protective approaches and toolkits with structures, behaviours and attitudes that help foster trust in elections. The four pillars of trust can be seen as a framework for discussing trust in electoral institutions, processes and officials, for detecting weaknesses and identifying areas that require improvement. They are not and cannot be a failsafe step-by-step instruction on creating trust or encouraging blind or undeserved trust.

[1] Cary Coglianese, Achieving Regulatory Excellence. Brookings University Press. 2016.

[2] Peter Drahos, Regulatory Theory: Foundations and Applications. ANU Press. 2017.

This article was initially published in the A-WEB India Journal of Elections Volume II Issue No 2 (October 2022-March 2023).