New government in El Salvador

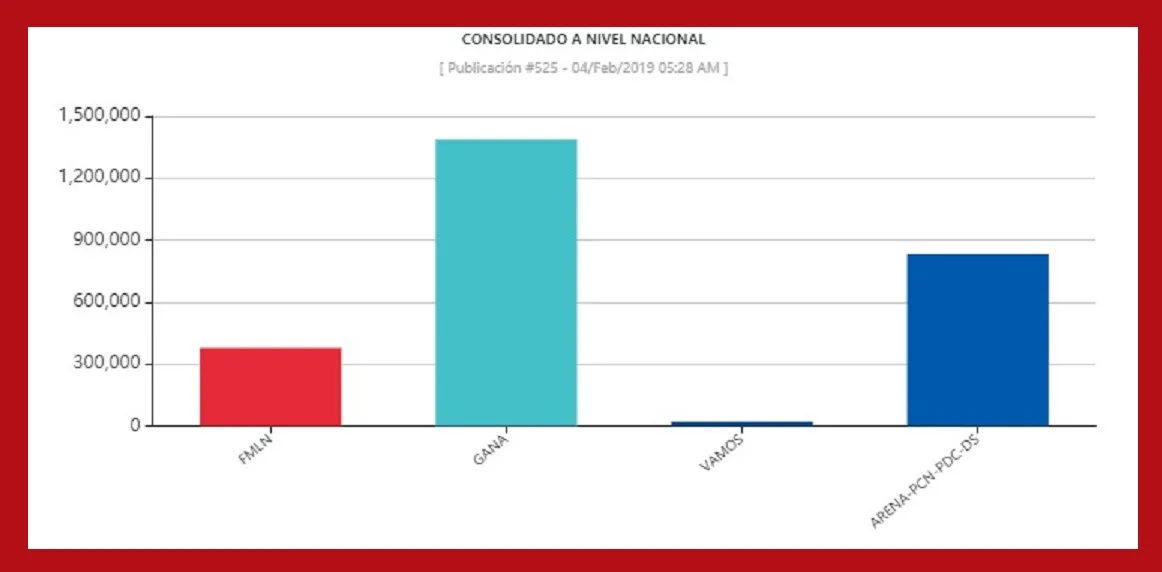

On Sunday, 3 February 2019, presidential elections were held in El Salvador. The victorious candidate with 53 per cent of the votes—according to the preliminary results—was to Nayib Bukele Ortez and his running mate, Felix Ulloa Garay, from the Great Alliance for National Unity (GANA). They overwhelmingly defeated Carlos Calleja (31.78 per cent), of the Alliance for a New Country (Arena-PCN-PDC-DS); Hugo Martínez (14.42 per cent), of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN); and Josúe Alvarado (0.78 per cent), of the newly created Vamos party. Bukele won in all of the 14 departments of the country by margins of between 11 and 20 points.

Este artículo está disponible en español.

By winning by more than 20 points over Calleja, Bukele reaffirmed the weekly polling trends: he got more votes than the other three political parties combined. Moreover, contrary to the regional trend—where all the elections of the so-called "super electoral cycle" in Latin America (2017-2019) held in countries that contemplated the second round and required the use of such mechanism—his victory made it unnecessary to hold a second round, being this another singular element of his success.

Bukele, 37 years old, ran for election as an anti-system candidate; however, during most of his political career, he had the protection of one of the two traditional parties of El Salvador, the FMLN. In 2012, he was elected Mayor of Nuevo Cuscatlán, a small town, 8.5 km from San Salvador, and in 2015 he won the Mayor's office of the capital. Bukele then was expelled from the FMLN on 10 October 2017 for violating the principles of that political party. Subsequently, that same October, he announced the creation of the New Ideas movement, which sought to be a political party. In June 2018, ahead of the presidential elections, he forged an alliance with Democratic Change (center-left); nonetheless, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal canceled the political party registration after processing a 2015 lawsuit. Bukele then decided to participate in the internal election of GANA, in which he obtained 91.14 per cent of the votes.

The triumph of Bukele entails two things. Firstly, and in line with the most recent electoral results in Latin America and the world, a defeat of traditional parties—as it happened in Mexico and Brazil. And secondly, the end of a 26-years long bipartisan ruling in El Salvador at the hands of an anti-system candidate that took advantage of citizens' discontent with traditional politics, rampant corruption and unrestrained violence and insecurity.

One of the main factors to explain Bukele’s victory was his clever and intensive use of social media—given that he is a successful publicist—with special attention to citizen’s anger, mainly that of the young. He abandoned the usual ways of campaigning as he almost did not hold rallies, interviews, visits or debates (except official ones). His critics emphasized the little contact with the people, which was replaced by a very well formulated and publicized image.

In any case, the new president faces important challenges. El Salvador is the country with the highest murder rate in the world, which keeps many communities in poverty and has generated substantial migratory flows. Unemployment and low economic growth also add up to the complex scenario Bukele will have to face.

The new government is expected to offer results in a relatively short period of time, especially when it comes to the fighting corruption, one of Bukele's most important commitments during his campaign—"money is sufficient when no one steals" was one of his campaign slogans. Moreover, there are expectations about the scope and powers of the commission against impunity, whose creation was announced recently, will have international support and was inspired by similar exercises in Guatemala and Honduras. It is worth noting that El Salvador ranks 112 out of 180 in Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index. On top of that, the most skeptical have questioned the feasibility of these plans under the argument that GANA—the party that nominated Bukele—was founded by former President Antonio Saca—convicted to 10 years in prison for misappropriation and money laundering—and has among its ranks other individuals involved in similar scandals.

Institutional factors, such as the potential conflict with the legislative branch, make the future a bit more complicated. The current Legislative Assembly—elected in March 2018—has a majority representation formed mainly by the traditional parties (66.2 per cent of the seats are distributed between Arena and the FMLN). Nevertheless, the main figures in the Assembly have recognized the victory of Bukele and have expressed their willingness to collaborate with him. But given the precariousness of the structure that led Bukele to power, unnecessary to win the presidential election but paramount to build parliamentary majorities and agreements, major battles are expected.

Finally, in regional politics, balances and alliances are likely to change. Bukele has criticized both Daniel Ortega's government in Nicaragua and Maduro's government in Venezuela. Thus, it is expected that the previous support fostered by previous FMLN governments will turn into detachment or even confrontation, especially with Nicaragua. This could eventually add an element of tension in Central American geopolitics.