Latin American democracy faces its midlife crisis

Disclaimer: Views expressed in this commentary are those of the staff member. This commentary is independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

Este artículo se encuentra disponible en Español.

Democracy in Latin America is facing its midlife crisis just as we approach the 40th anniversary of the beginning of the Third Wave in our region. The data from the Latinobarómetro 2018 survey warn us that democracy is facing problems: support for democracy is waning, dissatisfaction is rising sharply, and the number of those indifferent to democracy is growing while support for authoritarian governments remains stable at 15 per cent.

The level of support for democracy, at 48 per cent, has lost 5 points, its lowest point since the 2001 crisis. Venezuela (75 per cent), Costa Rica (63 per cent), and Uruguay (61 per cent) are the three countries with the strongest support for democracy. The least support for democracy was found in Honduras, with 34 per cent; and Guatemala and El Salvador, with 28 per cent each.

The percentage of those who are indifferent (as between democratic and authoritarian government) has climbed from 16 per cent to 28 per cent, especially among youths ages 16 to 26 years; this is a serious matter given the possible future consequences. El Salvador, with 54 per cent, and Honduras with 41 per cent, have the highest levels of indifference in all Latin America.

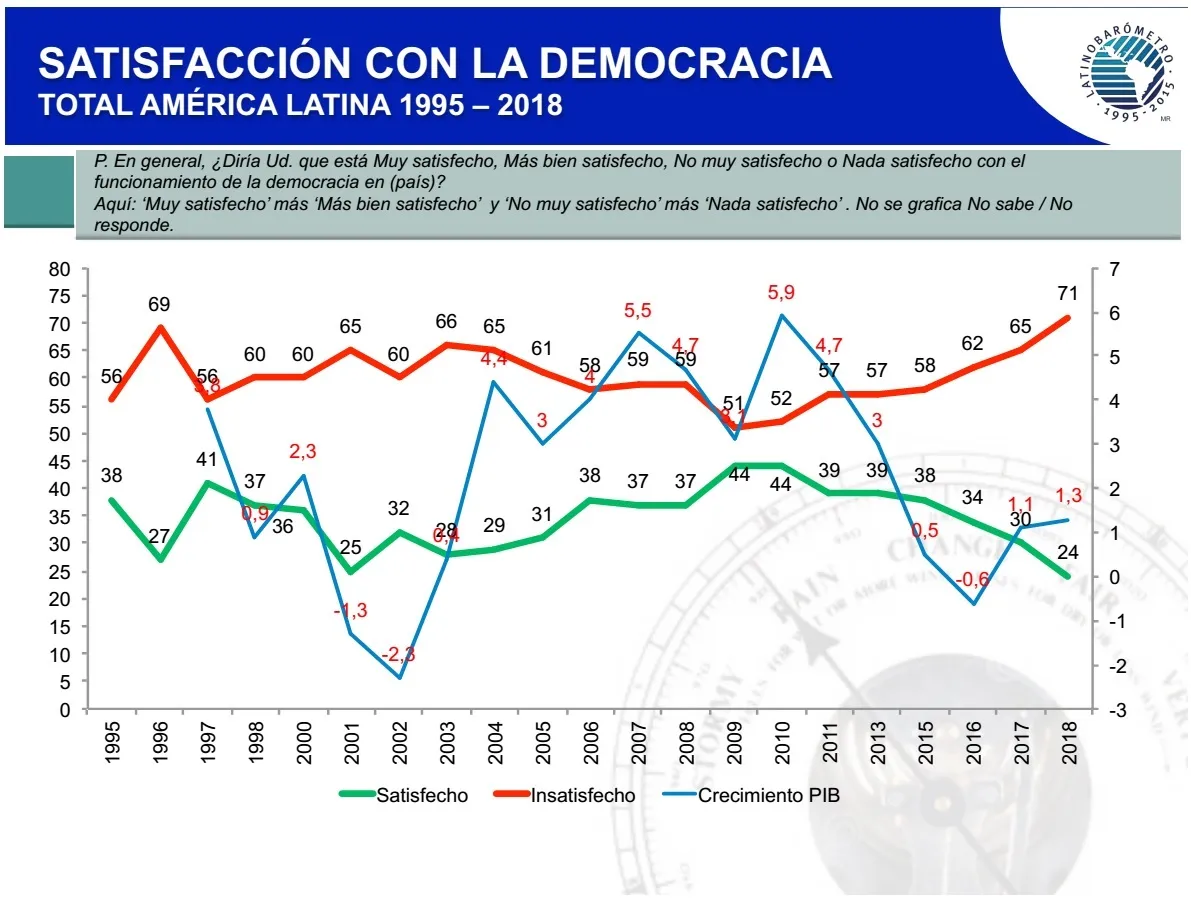

Dissatisfaction with democracy rose from 51 per cent to 71 per cent, while satisfaction plummeted from 44 per cent to 24 per cent.

Economic issues are the main concern: 84 per cent are dissatisfied with the performance of the economy. Except in the cases of Bolivia, Chile, and the Dominican Republic, Latin Americans feel that their countries are stagnant: 49 per cent are of the opinion that there is no progress, 28 per cent that they are backsliding, and only 20 per cent believe that they are progressing. For 79 per cent their country is governed by a few powerful groups for their own benefit; only 16 per cent consider the distribution of wealth to be just.

Crime is the second leading problem in order of importance and leads the list of concerns even in relatively safe countries like Chile and Uruguay. Guatemala and Honduras are the two countries in the region where one finds the greatest fear of becoming a crime victim.

Despite the serious and widespread corruption scandals in the region, in only seven countries does this scourge occupy a significant place on the public agenda: Colombia, Peru, Brazil, Bolivia, Mexico, Paraguay, and the Dominican Republic.

This feeling of discontent and frustration has a negative impact on the levels of trust in the institutions, with an especially detrimental impact on the legislatures and political parties. The churches and armed forces are the two institutions that enjoy the highest levels of trust.

The data from Latinobarómetro 2018 show that voters continue moving away from the political parties, and that they are angry and upset with politics and the elites, facilitating the emergence of populist and anti-system candidates on both the right and the left. The recent victories of Andrés Manuel López Obrador in Mexico and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil are two examples of this phenomenon. Low levels of support for democracy (Brazil with 34 per cent and Mexico with 38 per cent), the high level of indifference as between democracy and authoritarianism (41 per cent in Brazil and 38 per cent in Mexico), and an anemic level of satisfaction with democracy (16 per cent Mexico and 9 per cent Brazil), combined with mediocre economic performance and high levels of corruption and insecurity, all driven by bad use of social networks and the propagation of fake news, all combine to favor the emergence of such anti-system leaders. It remains to be seen whether a similar phenomenon finds expression in any of the six presidential elections to be held in 2019: El Salvador, Panama, and Guatemala in Central America, and Bolivia, Argentina, and Uruguay in South America.

A final thought: this decline in the indicators of political culture coincides with the deterioration in the quality of democracy in our region. According to the 2017 Democracy Index, pulled together by The Economist Intelligence Unit, only Uruguay qualifies as a “full democracy.” Ten countries are considered “flawed democracies.” And three Central American countries, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua, along with Bolivia and Paraguay, are classified as hybrid regimes. Finally, Venezuela and Cuba are qualified as authoritarian regimes.

What is the main cause of this discontent and frustration with democracy? The lack of results. Latin Americans are not asking for more authoritarianism. Less ideologized and more pragmatic, less patient and more exigent, what citizens are demanding is that their governments listen to them, govern with transparency, and respond in a timely and effective manner to their new expectations and demands. If we want to improve citizen support for democracy and satisfaction with it, we must improve people’s quality of life.

Is there a risk of a generalized collapse of democracy in the region? Not in the short term. Yet if the quality of democracies continues to deteriorate then there is the risk that the current populist and authoritarian trends will grow dangerously. In this scenario, an ever greater part of the citizenry would be willing to sacrifice pieces of democracy in exchange for better economic wellbeing and greater security. Either we act quickly and intelligently or we run the risk of this discontent in democracy becoming discontent with democracy. The new decline in support for democracy and the major increase in those who are indifferent are two warning signs that demand attention and action.

What is to be done? Set in motion a renewed agenda that aims to recover citizen trust in politics, the political elites and institutions, expand the spaces for citizen participation, and guarantee effective citizenship, all with the objective of strengthening governance, improving the quality of public policies, and laying the bases for a new generation of democracy that is inclusive, prosperous, and, above all, resilient, i.e. with the capacity to confront complex crises and challenges, including the disruptive changes of the fourth industrial revolution, surviving them, innovating, and recovering.

We are going to engage in an in-depth dialogue on these issues and many others at the international conference co-organized by International IDEA and the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) on 26-28 November 2018, in Santiago, Chile.

The conference begins on Monday, 26 November, with a panel on the “State of Democracy in Latin America,” which will be moderated by Daniel Zovatto (Regional Director of International IDEA), which will include the participation of former presidents Ricardo Lagos (Chile), Laura Chinchilla (Costa Rica), and Luis Alberto Lacalle (Uruguay), along with Gonzalo Blumel (Minister of the Ministry/General Secretariat of the Presidency of Chile), Sergio Bitar (Member of the Board of Advisers, International IDEA), and Alicia Bárcena (Executive Secretariat of ECLAC).

Relevant Information related to the Conference is available here.

To register for the Inaugural Panel, click here.

To register fo the Closing Panel, click here.

Both the panels will be live telecast here.