The current challenges to electoral democracy in Australia and India

Disclaimer: Views expressed in this commentary are those of the staff member. This commentary is independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

MELBOURNE - The International IDEA Global State of Democracy Indices data supports that procedural democracy (particularly elections) is in good health in India and Australia, consistently outperforming global and regional averages.

There are, however, major challenges posed to electoral processes and public trust in them worldwide by the impact of social media and cyber-hacking. Both the Australian Electoral Commission and the Electoral Commission of India are taking important steps to respond to these risks.

INTRODUCTION

The major challenges facing democracy in India and Australia are in the more diffuse areas of substantive democracy, such as the protection of fundamental rights, which of course unavoidably spill into the electoral process.

The graphic below illustrates how democracy is conceptualised at IDEA1, which consequently forms the spine of IDEA’s Global State of Democracy (GSOD)2 data.

Elections run well are an immensely valuable indicator of a healthily functioning democracy, but alone they are not enough.

As can be seen, election-related indicators fall under broader themes such as ‘Representative Government’ and ‘Participatory Engagement’ and are, of course, intimately related to the other indicators in the GSOD framework.

The State of Electoral Democracy Globally, democracy is under strain and may be experiencing its most severe crisis in modern history.

The past four decades have seen a remarkable expansion of democracy throughout all regions of the world, and democratic transitions continue to occur. But recent years have been marked by a decline of democratic performance in both older and more recent democracies.

The GSOD data specific to electoral processes since 1975 reflects fundamentally stable and resilient electoral systems in Australia and India. Indian electoral democracy in particularly has shown continuity, despite diversity of class, caste, ethnicity and religion, as well as sheer size.

In terms of IDEA’s measures of electoral participation and inclusive suffrage, Australia and India display impressively high scores, which are well above the increasing global and regional average for Asia and the Pacific.

Australia’s electoral participation has remained high, recognising that Australia has compulsory voting, while India has seen a major increase since the 2014 national election, climbing above the regional and global average. Voter participation in India increased further in 2019. India’s establishment and maintenance of universal adult suffrage since the end of colonial rule is particularly impressive, preceding other advanced democracies such as the USA.3 Australia benefits from the data beginning in 1975, just after the enfranchisement of all Indigenous/Aboriginal Australians.

The growing challenge of ‘clean elections’ India and Australia are again well above global and regional averages, according to IDEA’s measure of clean elections is an amalgamation of factors such as competition, autonomy and capacity of Electoral Management Bodies (EMBs), government intimidation, smooth organisation of the electoral period and polling day. But both nations have nonetheless seen declines in the past decade.

When asking why this decline, one can point, for example, to the Australian Electoral Commission losing ballots in 2013 Senate Elections (https://www.abc.net.au/news/2013-11-04/wa-set-tohead-back-to-polls-in-six-senate-by-elections/5066718).

To put these trends into a regional context, India’s position in 2018 is almost exactly that of the European average, while remaining considerably above the regional averages for Latin America and Africa.

CONDUCTING A CLEAN ELECTION HAS BECOME MORE DIFFICULT IN RECENT YEARS

Old regulatory models no longer hold up in the face of social media as new platform for electoral competition, as well as the threat of cyber-hacking.

The risk of cyber-hacking was thrust into the spotlight in Australia earlier this year in February, when the Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, announced that the Australian parliament and political parties had been hacked by a ‘sophisticated state actor’. The Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) identified 1097 cyber incidents considered serious enough for operational response (2015-2018).

Philip N. Howard, professor of Internet studies at the Oxford Internet institute, made statement during hearing of Senate Intelligence Committee on foreign Influence on Social media (2018) that India could be next.

Micro-targeting – the use of individuals’ personal data to target them with campaign messaging – is becoming an ever more common strategy of political parties – the use of third-party companies like Cambridge Analytica for the US elections has revealed major transparency and accountability issues.

Beyond the immediate risk of influencing voter behaviour or even polluting the actual result, cyberhacking and social media manipulation threaten to undermine public trust in the election process as a whole.

This challenge of public trust is difficult for any single national EMB to manage because it is so dependent on events worldwide. The fallout from the 2016 election in the USA has reverberated across the globe. A survey conducted by the Electoral Integrity Project, I found that 4 in 10 Australians thought that fraud was likely to impact the outcome of the 2016 federal election, although 2 in 3 still said they were very or somewhat satisfied with the overall fairness.

IDEA’s current agenda is heavily focused on working with EMBs to manage electoral risk, including that of social media platforms. It is promising to see that Australia and India are taking important steps to respond to these new risks.

Australia:

- The Foreign Influence Transparency Scheme and the Electoral Integrity Taskforce established in 2018, respond to threats and disseminate information to the public on the nature and extent of foreign influence on elections.

- The Taskforce, which co-operates with the security agencies, government departments and local electoral commissions, fits the mould of the ‘inter-agency collaboration’ that IDEA called for in our recent discussion paper on Cyber-Hacking.

- The AEC has impressively integrated risk management into its 2018-2022 strategy, creating a framework that isolated their mission, the risks associated with each aspect of it and the opportunities for modernisation that arise from these risks.

India:

- The widespread use of social media has left EMBs with nowhere to hide if they make any sort of mistake and often have those mistakes magnified.

- The ECI is taking steps to harness technology to improve its risk management in elections through the app cVigil. Voters use the app to report electoral code violations, with photos and videos as evidence. It enables Very direct interaction with voters - 142,250 issues were raised of which 80% of which assessed as correct - to increase confidence in elections.

THE STATE OF DEMOCRACY IN GENERAL

IDEA is observing a global phenomenon of democratic ‘backsliding’, which is the theme of our 2019 GSOD report. We are having to question the assumptions that we began with during the wave of democratisation in the 1990s about the unstoppable advance of democracies worldwide.

This ‘backsliding’ unavoidably spills into electoral processes. For example, one troubling global trend is that of the is receding independence of EMBs. The institutional resilience and independence of the ECI and AEC is not to be taken for granted.

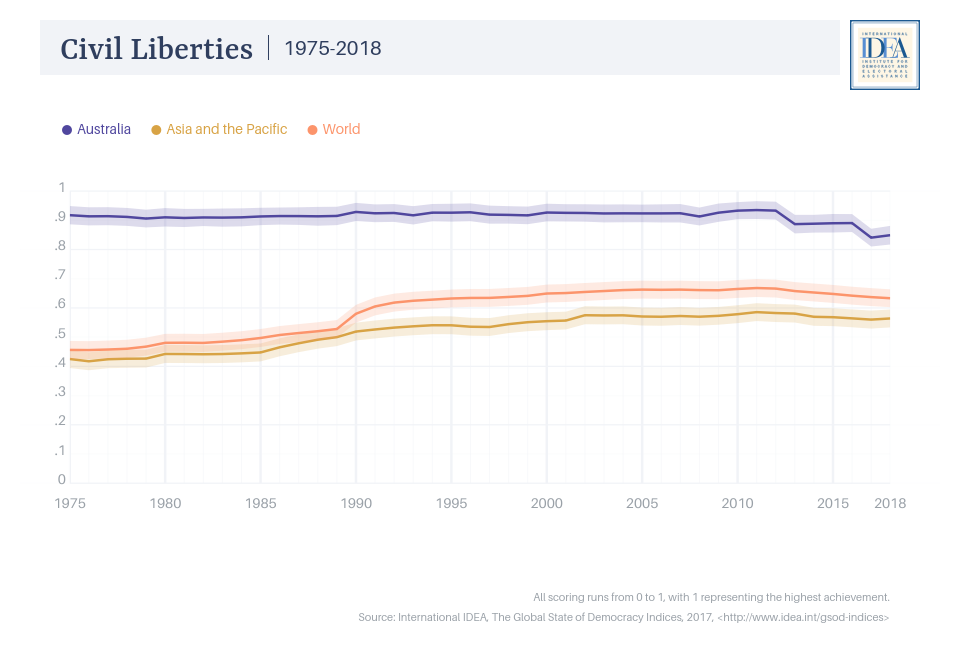

It emerges from the GSOD data that the major challenges facing the health of democracy in Australia and India are not aspects of procedural democracy, such as the operation of an election, but rather the more diffuse aspects of democratic society that inform and influence the procedures, such as civil liberties.

AUSTRALIA AND INDIA HAVE BOTH SEEN DECLINES IN FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS AND CIVIL LIBERTIES

Explanations for the lower score for Australia can be sought from different areas. In one case, Australian Federal Police admitted to accessing journalists’ metadata without special warrants required.

Furthermore, there have been concerns raised by UN Special Rapporteurs on free speech; and terrorism and human rights defenders, on the potential for broadly-worded espionage offences in National Security Legislation Amendment (Espionage and Foreign Interference) Act 2018 to restrict expression and access to information central to accountability and public debate.4

In India, although IDEA’s indicators show it is placed above South Asia, there has been a decline on this front since 2015 dropping India below both the global and Asia Pacific standards during this period.

Access to justice has also been in decline since 2015 to a point which is almost similar to the period of the Indian Emergency. There also been backsliding in civil liberties, with a sharp fall from 2015 onwards to the point where it has fallen below South Asian and global scores in 2017. The CIVICUS policy brief of 2017 has described India as having a “restricted” civic space. Also, freedom of religion has dropped, and the dip has been pronounced since 2013.

1. Checks on Government

While the effectiveness of parliament and independence of the judiciary have remained stable in recent years in their function of holding the government accountable, media integrity has been the source of India’s decline in this indicator. Australia’s scores have remained stable and high.

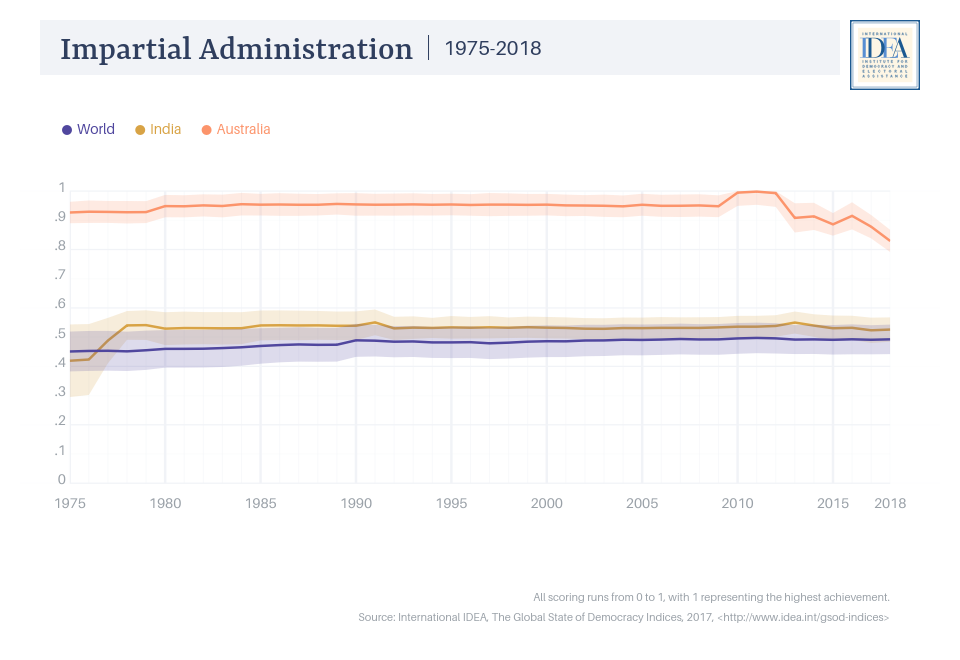

2. Impartial Administration

This refers to the absence of corruption and predictable administration. By this measure, India has remained stable and above the global and regional average for Asia and the Pacific. Australia, while starting from a very high base, has fallen in this indicator significantly since 2013 possibly due to privatisation and outsourcing of public sector work, which impacts security, privacy and transparency of government; and theand stonewalling of Freedom of Information requests.

Technical, normative and developmental work by many actors in the field of electoral management, support and research has paid dividends. There is a knowledgeable, global peer community of election administrators, civil society activists and organisations that not only organise and observe elections, but also defend electoral integrity when challenged.

There is, however, little room for complacency. The new challenges to electoral democracy are out of reach and beyond what a steady and sound professional approach to election administration can counter.

These challenges come in nefarious new guises (cyber-hacking and fake news) and familiar ones (incumbency advantage and vote buying). Simply put, it is the willful thwarting of a level playing field by political actors. This deliberate game-playing of established systems for personal political gain is of such proportion that regulatory success, for example, regulating political finance, put in place by electoral authorities to guarantee a level playing field cannot possible keep up with it. As UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres puts it, electoral democracy needs political leadership

----

1 I wish to thank Martin Brusis, Andrea Garland and Robin Watts from International IDEA for compiling the relevant GSoD data on Australia and India.

2 Developed from multiple traditions of political thought -- electoral, liberal, social and participatory democracy -- designed as “health check” on democracy across time and geographical regions - to deepen understanding of how democracy actually functioned in the 155 countries that were surveyed.

3 Point made in Sumona DasGupta India country report, p5-6. (to be published as part of International IDEA Global State of Democracy Report).

4 Tom Daly Australia Country Case study in the forthcoming International IDEA Global State of Democracy Report.

This commentary originally appeared in the ElectionWatch of the Melbourne School of Government.