Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

This is the second blog in a three-part series on Thailand’s senatorial elections. The first blog in the series, which outlines the complex electoral process, can be read here.

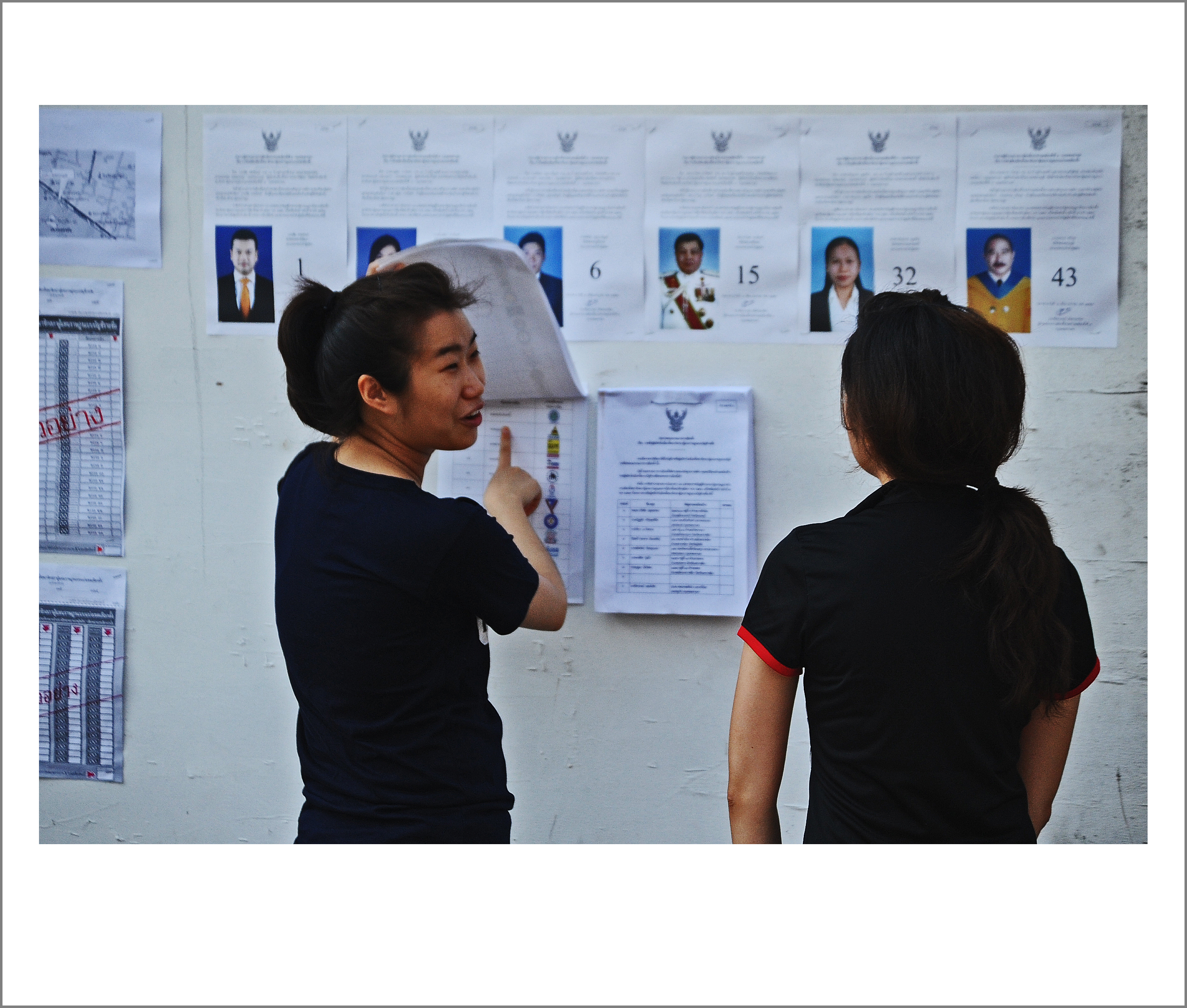

Thailand’s senatorial elections (9-26 June) will be a convoluted and largely stage-managed affair. Rather than an open competition, Senators are selected ‘by and among persons having the knowledge, expertise, experience, profession, characteristics or common interests or working or having worked in varied areas of the society.’ This electoral process was designed to ensure the royalist, military and business interests that make up the country’s political establishment will retain a stranglehold on the chamber. But long odds do not mean the senatorial elections are not a key juncture for Thailand and beyond.

First of all, reformist candidates do not need to win the election outright, only to secure at least one-third of seats in this or a future Senate to pursue the goal of amending the 2017 constitution in service of wholesale constitutional reform. (International IDEA 2023). This is still a tall order: the cost of participation in Senate elections is prohibitively high for most Thais, and those who can afford to pay it – like university professors or civil servants – are required to resign in order to put themselves forward as candidates. Further, candidates cannot be members of political parties and so cannot access political party supports for campaigns.

Incremental Change

That said, democratic reformers can make headway even without passing the 30 per cent threshold for constitutional amendment. Following the Move Forward Party’s (MFP) surprise victory in the 2023 general elections, the Thai defence ministry announced plans to progressively abandon conscription and reduce the number of senior staff – a key plank in MFP’s electoral platform. While amending the constitution without establishment consent is an unlikely near-term possibility for Thai democrats, more reformist Senators means more leverage to extract concessions and increased influence over executive appointments – another tool the establishment has relied on to stifle reform and protect the post-coup status quo.

These are best case scenarios, and to achieve them democratic reformers may need the help of diplomatic pressure to ensure the establishment plays by the stated rules. Such help has not been overwhelmingly forthcoming, either out of economic interests, a belief that the incoming senate being marginally better than its predecessor is sufficient, or the worry that pushing the establishment too hard would pave the way for another coup.

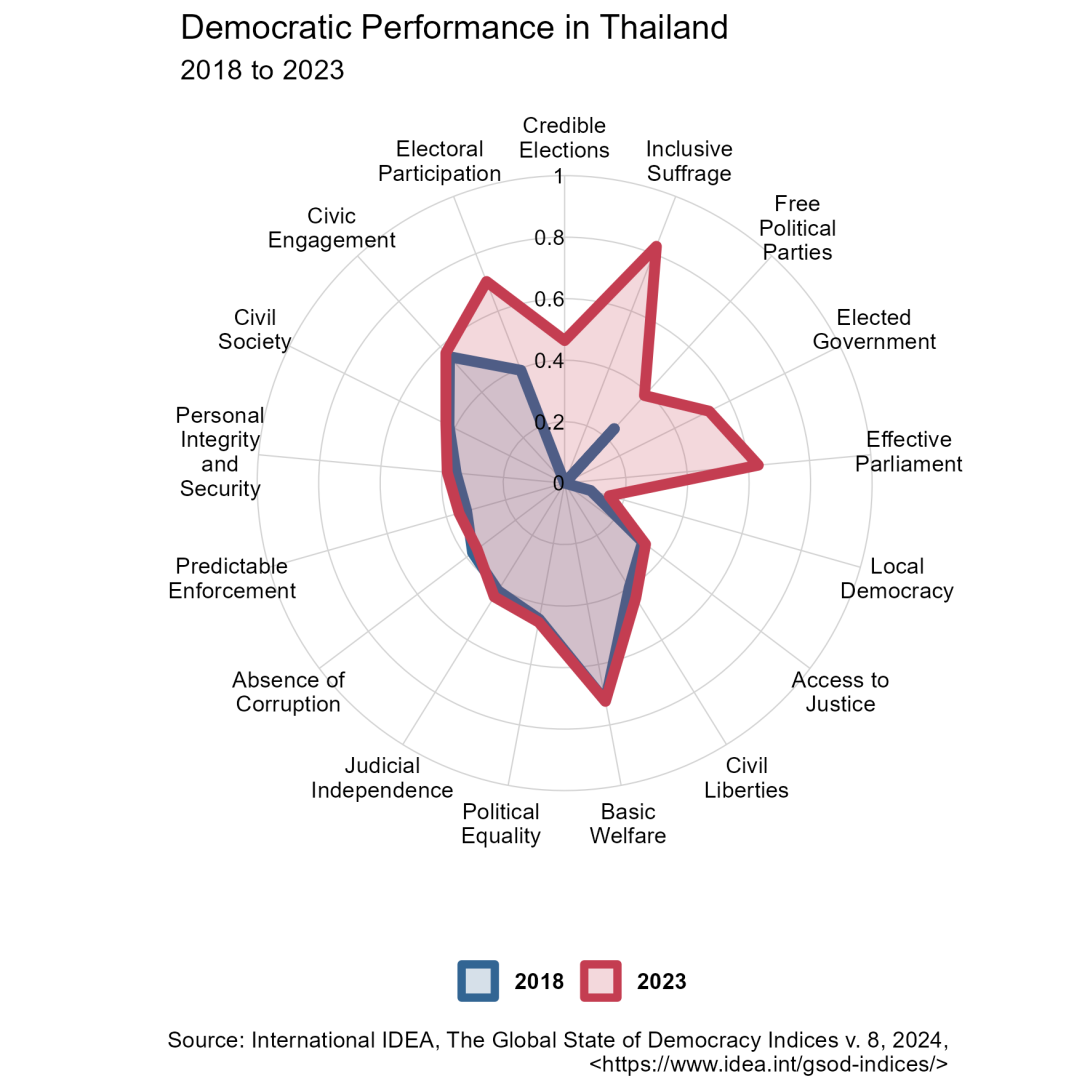

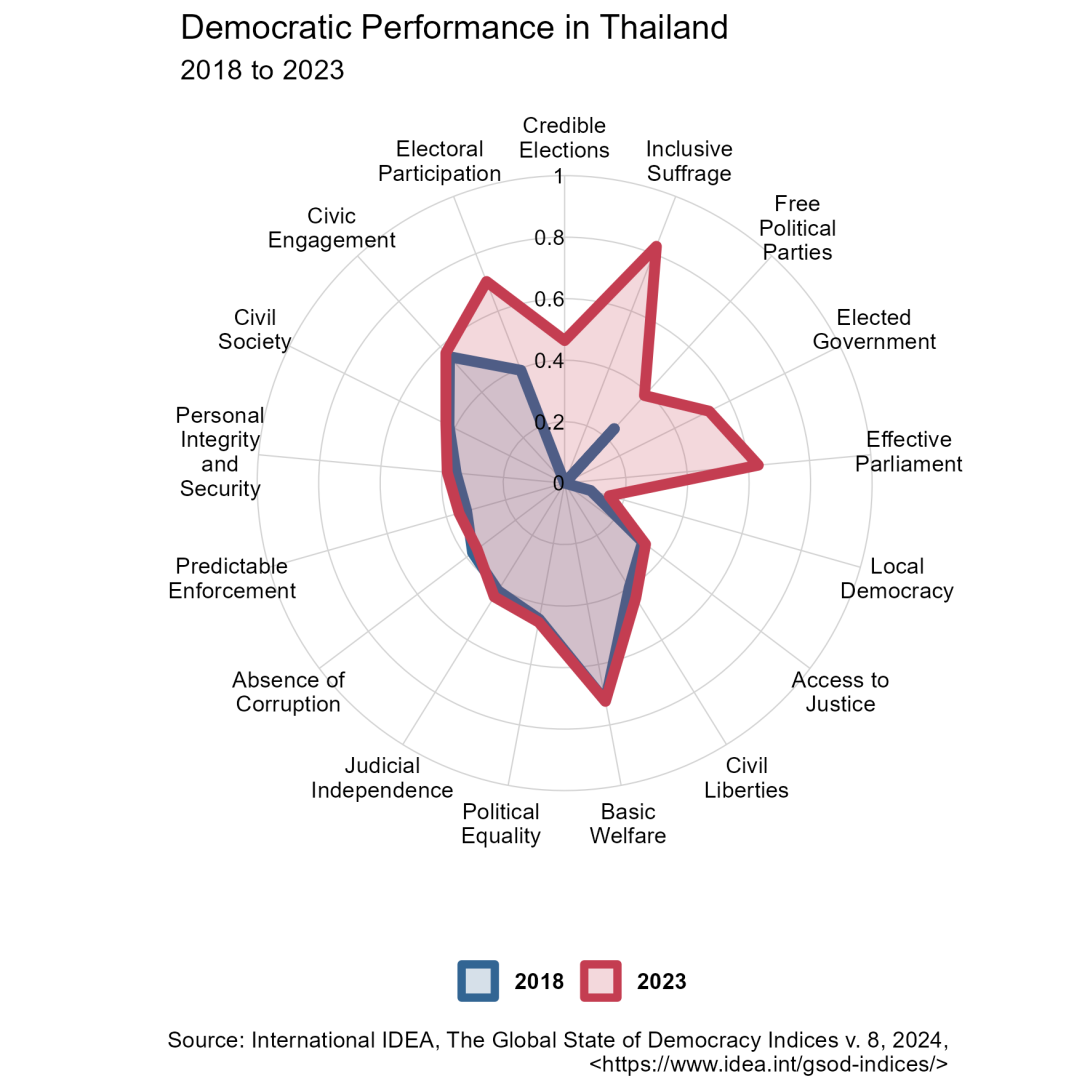

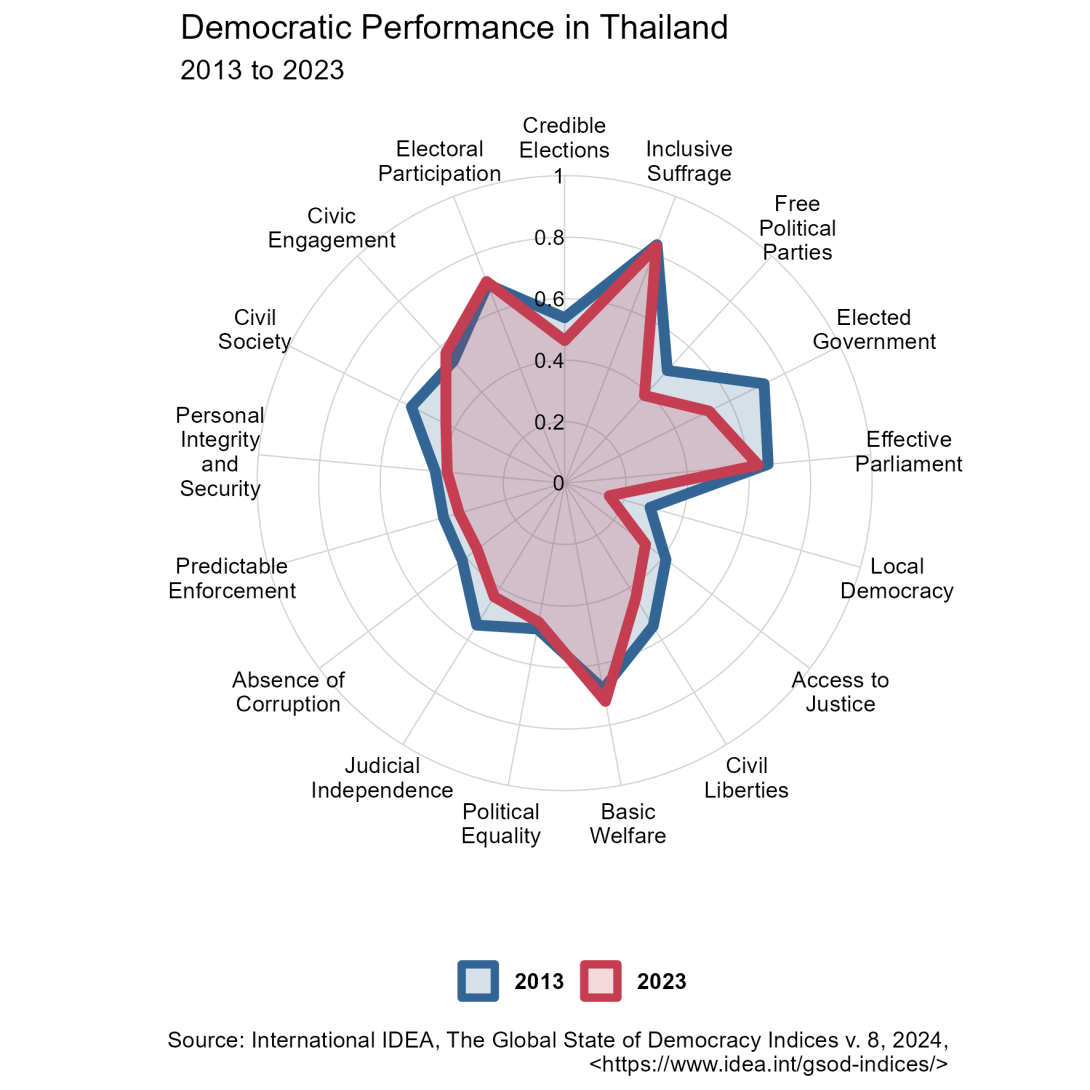

As the latest Global State of Democracy (GSOD) data shows, Thailand’s democracy has markedly improved over the last four years, particularly in the measures of Credible Elections, Effective Parliament and Elected Government:

Managed Democracy

But placed in broader context this progress appears less impressive, and the validity of gradualists’ more extreme concerns is likely overstated. This means the most serious risk in letting “the most complicated elections in the world” pass without major notice is instead the further entrenchment of managed democracy in South-East Asia: a state where democratic processes are carried out to not to allow the governed to choose those who govern, but to extract mandates for elite rule in return for the absolute minimum of policy concessions.

The GSoD Indices are a useful tool for assessing whether Thailand is returning to its more democratic pre-coup state or settling into a more hardened managed democracy of some form: while Thai democracy has certainly recovered significantly since the 2014 coup, it continues to seriously lag the status quo ante. As seen below in Figure 2, political parties are less free, less of the government is elected and civil society is more restricted.

In other words, we are seeing the return of democratic processes in form, but not yet in substance. There is little ground here for gradualist optimism. The Move Forward Party, the winners of last year’s election and the, current vehicle for popular dissatisfaction with the establishment and demand for constitutional reform, is currently facing dissolution. But this and other setbacks have not stopped democratic reformers from pushing for change. They deserve more international support now, during, and after the elections.