The storm that comes: information manipulation of electoral results

Images of Keiko Fujimori supporters protesting the electoral results in Peru, or Donald Trump acolytes storming the Capitol on January 6th are bound to become more common. Attacking the legitimacy of electoral results is being added to the disinformation playbook of illiberal forces all over the world, and this threatens the quality of democracy globally by attacking the glue that holds democracy together: trust.

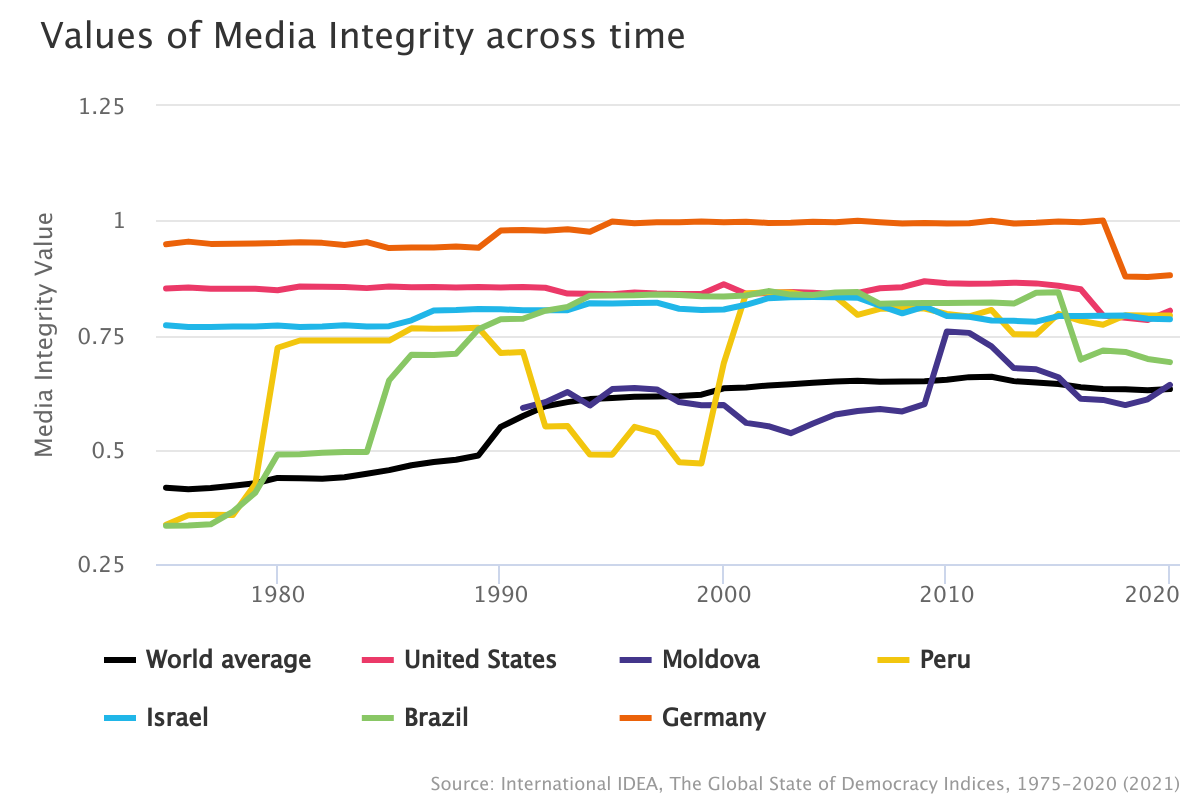

Without trust in the results, the legitimacy of elections becomes vulnerable. This vulnerability is well known, and we are witnessing its exploitation around the world. We are seeing an increasingly common pattern: In the weeks (or even months, such as in Brazil or Germany) before the election, political actors will subtly question the integrity of the electoral process, sowing a seed of doubt among their supporters. Afterwards, if results are not leaning towards the candidate or party, a coordinated disinformation campaign will be unleashed online, and any excuse will be used—mail-in voting, voting from abroad, counting of votes in certain areas of the country, double voting, undocumented immigrants voting—to send a clear message: results cannot be trusted.

How is this possible? First, coordinated disinformation campaigns online make it possible for certain leaders’ false narratives to grow over time. The narrative of leaders or parties in the US, Peru, Moldova or Germany was sustained by an orchestrated campaign online to support it. Second, fraudulent counting and tabulation can sometimes occur. In fact, these methods have long been used to rig elections. Yet, today such instances are less and less common as rigging elections becomes more sophisticated1 . Still, political operatives continue to use it as justification. Third, questioning the results this way may provide a small opening to overturn them. In Moldova, losing incumbents questioned the results to influence a second round. In Israel, it decreased the support a possible coalition capable of unseating the ruling party might have had. More dangerous attempts might be taken to justify a repetition of the elections or even a military take-over, such as the one that took place in Myanmar.

This kind of campaign helps build a populist narrative based on the idea that the incoming government is not legitimate. This narrative simultaneously attacks the incoming government, the electoral management body and the media landscape, threatening three fundamental pillars of democracy.

These attacks leave a serious dent in democracy. They erode trust in the system and its rules, which subsequently erodes the legitimacy of democratic institutions. The use of coordinated online manipulation campaigns that unjustifiably question electoral results is something of a novelty that needs to be addressed before it becomes the norm after elections. To start addressing the problem, three action points are key.

Firstly, civil society and educational institutions must prioritize broad voter education campaigns to make voters and citizens aware of what disinformation looks like and why it is dangerous. Secondly, electoral management bodies and other stakeholders must enhance electoral transparency throughout the process, especially during voting, counting and tabulation.

Last but not least, it is critical to set up a multi-stakeholder approach that includes technology platforms, governments and civil society to make sure social media is at the service of electoral integrity. This can be realised through targeted takedowns, flagging of voting-related disinformation and pre-emptive measures ahead of voting and tabulation processes to stop inauthentic behaviour and false narratives. These measures would reinforce trust in elections. Without trust, it not only elections that are at risk; democracy itself could go into freefall.

[1] On the current trends to rig elections, see “How to Rig and Election” by Nic Cheeseman and Brian Klaas

Photo by Clay Banks on Unsplash.