The State of Democracy in Asia and the Pacific 2023

In early 2023, two promising democratic developments were on the horizon: in Thailand, the Move Forward Party was rapidly rising in pre-election polls, raising hopes that this novel, left-leaning social democratic party would push the country back towards democracy. In Australia, years of campaigning would culminate in a referendum on creating an Indigenous Voice to Parliament, an advisory body that would provide indigenous views on the federal level.

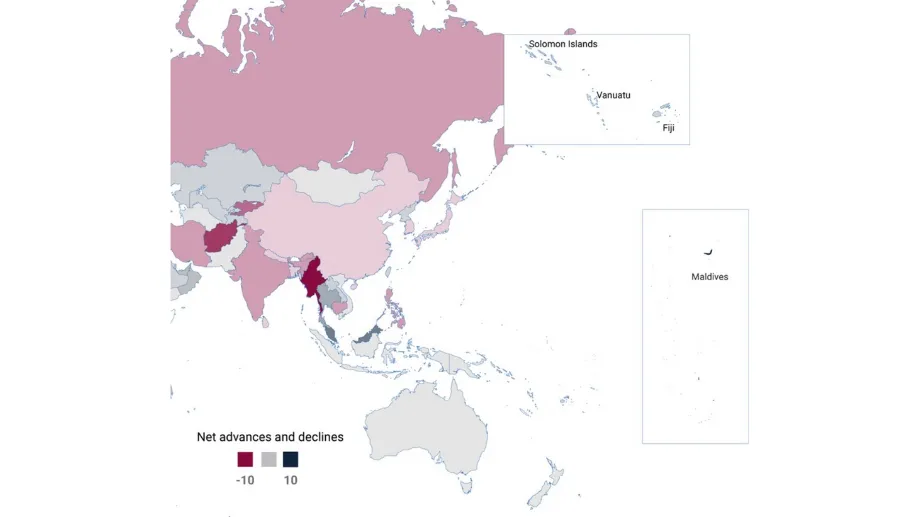

Neither came to pass – Move Forward’s resounding victory in May elections was stymied by the country’s conservative military establishment. Australia’s referendum on its indigenous advisory body ended in defeat and catastrophe, a “vote for a tortured status quo.” This pattern, one of raised hopes of democratic innovation and a break from the stasis and slow decline of the last few years, has repeated, in differing iterations, across the vast region. Even though the latest data from 2022 indicates the broad democratic decline of recent years has mostly come to a halt, most countries in the region continue to score below the global average in Rule of Law, Rights and Representation. Civil liberties are also suffering. After peaking in 2012, the region’s aggregate Freedom of the Press score has now reverted to 2001 levels. Significant declines have occurred in countries as varied as Australia, Kyrgyzstan, the Philippines, South Korea, Sri Lanka and Taiwan.

That said, this trend is not universal: Malaysia and the Maldives saw significant advances in Representation in the last five years, and together with Sri Lanka and Thailand saw similar advances in Credible Elections. Significant improvements in Rule of Law (Maldives, Taiwan and Uzbekistan) and Representation (Malaysia, Maldives and Thailand) are also cautiously promising.

A double bind in Asia and the Pacific

Across the region, systemic problems with frontline countervailing institutions like parliaments and the suppression of freedom of association have left the role of defending democratic institutions to judiciaries, anti-corruption commissions and at times even mass street protests.

While these issues have varied domestic causes, the frequency with which they occur across the region also suggests international drivers.

Distribution of Rule of Law scores by subregion 2022 (median scores for subregions annotated)

One such driver is geopolitical, where low- and middle-income nations are arguably subject to the most external pressure. Despite the efforts of Asian governments to focus international diplomatic relations on questions of development aid and assistance, they increasingly operate in a world in which great powers are operating on principles of zero-sum and militarized competition (Kaiku 2023; Xiao 2022; Thu 2023; Needham 2022).

In parallel to this great power competition, the region is likely to experience the most significant long-term economic shock from the Covid-19 pandemic (Kothari and Tawk 2023).[1] These countries are also under continuing pressure from rising European and American interest rates that constrain and limit public policymaking (Arteta, Kamin and Ruch 2023; Iacoviello and Navarro 2018).

According to an April 2023 Asian Development Bank report, 23 countries covered by the GSoD Indices in the region are at high or moderate risk of being unable to manage their external debt in the near future (Table 5.1). A country overburdened with debt also imposes costs on its trading partners, as funds that could have been used to import goods or invest in productive enterprises are instead set aside for debt service.

If reversals of previous years’ democratic trends are to involve delivering on the social and economic goods that underlie democratic social contracts, many countries in the region face a continuing uphill battle (Stubbs et al. 2023).

Regional cooperation is key

Contrary to the developing status quo of ‘a more narrow and exclusive focus on maximizing the wealth and power of their state’ in international relations, countries in Asia and the Pacific would be better served by strengthening regional cooperation (Helleiner 2023). Regional networks, such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF), could theoretically act as a stabilizing and democratizing counterweight in a world of enhanced great-power competition—although internal political divisions have ensured no regional coalition has yet risen to the challenge (Damuri 2023; HRW 2022a).

Attempting to take stock of the state of democracy in the world can be an overwhelming and at times demoralizing experience. In the search for signs of hope, it is worth not losing track of the individual lives and stories that comprise these grand narratives. Across Asia and the Pacific, as well as in Asian diasporas around the world, human rights activists, labour organisers, and community networks continue to showcase the resilience of and popular demand for democracy. Those in positions of power in authority- parliaments, governments, election management bureaus, to name a few – should take note as well as inspiration. In 2019, the American magazine The Nation interviewed Brinda, a 61 year-old Nepali undocumented domestic worker in the United States, who said of her struggle, “democracy is what works in the world … I’m still a little nervous, yes, but whatever happens, happens. It’s not worth it to be depressed now. Plus, we’re still organizing.”

[1] Other analyses describe Latin America and the Caribbean as the region of the world most likely to suffer the most significant shock. However, neither the IMF nor International IDEA separate out Latin America from less-affected North American nations for the purpose of this or other analyses. A further subdivision of the countries of the world could lead to a different conclusion.