The new model of coups d'état in Africa: Younger, less violent, more popular

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

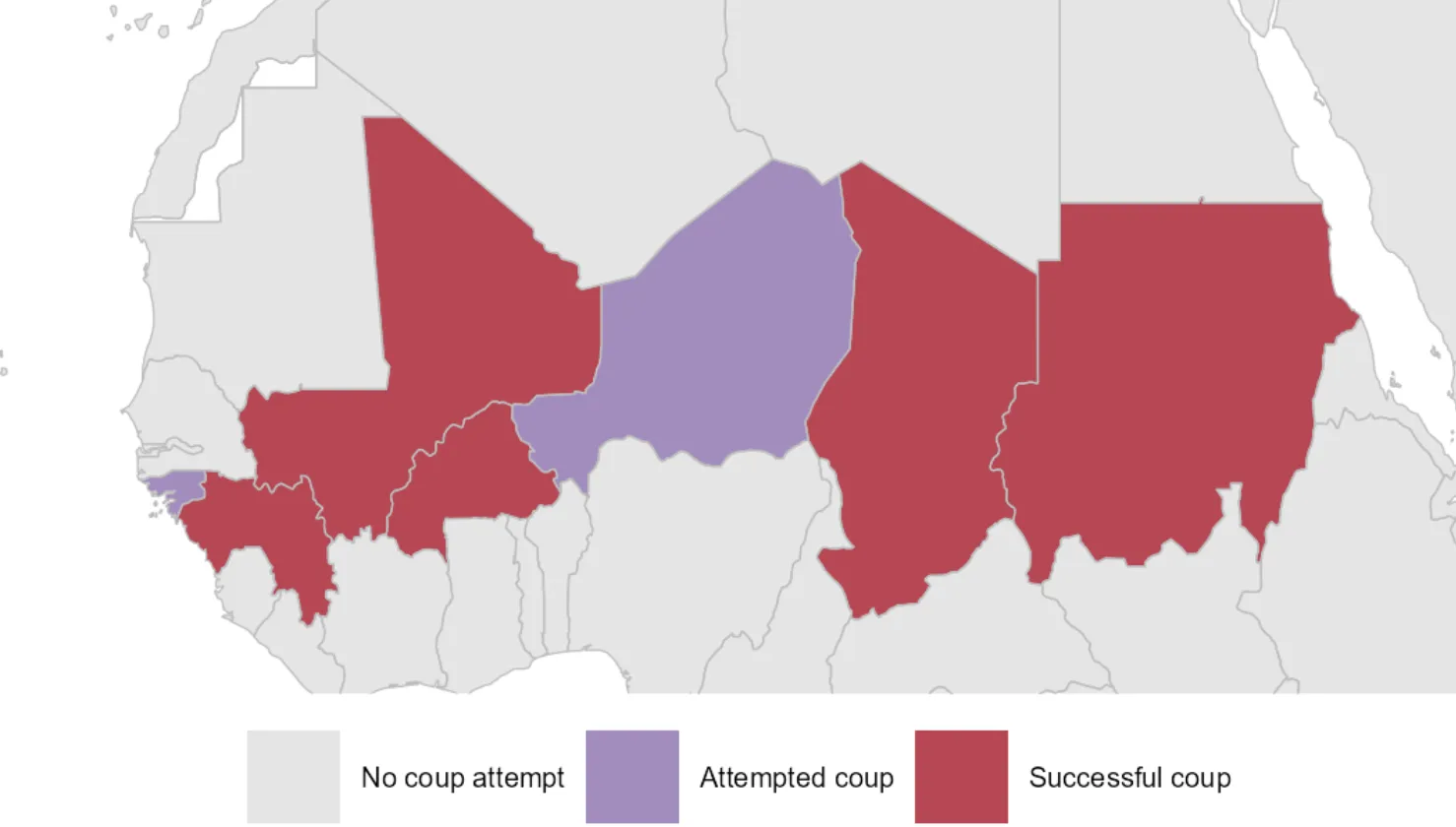

There have been nine attempted or successful coups d’état in Africa since 2020. A stereotypical coup d'état involves the most senior members of the military (i.e., generals) overthrowing the government in a short, but potentially violent, incident that causes mass panic in the population. The most recent coups in Africa differ in some key aspects from the coups that were seen on the continent in the past, especially during the immediate post-independence period. What are these differences, and what do they mean for democracy?

It seems that a new model of coup is being established, which differs in key ways compared to what has gone before. Coup leaders have been slightly younger, the coups have been less violent, and in some cases they have occurred (with popular support) against a background of political stagnation and intense security challenges. The type of foreign involvement in these coups also appear to be changing (but this is more difficult to confirm).

Younger leaders

The age of the coup leaders has been a remarkably consistent element of these most recent coups. With the exception of Sudan, the coup leaders have ranged in age from 34 to 41. They have also been lower in rank than most coup leaders (and have come mostly from special forces units), including two colonels, a lieutenant-Colonel, and a captain. This growing dynamic is certainly not completely unprecedented: Jerry Rawlings was a 31-year old flight-lieutenant when he led his first coup attempt in Ghana, and Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo was a 37-year old lieutenant-colonel when he seized power in Equatorial Guinea. The latter example also highlights a potential negative implication of this element of the current wave of coups: the leaders may try to stay in power for a very long time.

Minimal violence, popular support

The next two changed coup dynamics we highlighted are interrelated: their relatively non-violent nature, and the support (or at least lack of opposition) they have had among the general public. So called “bloodless coups” are a well established concept, but this is a notable commonality among the recent coups in Africa where, unlike before, incumbents have not been brutally assassinated and the ensuing death toll pales in comparison to previous coups (compare for example, the many people killed in the coups in Ghana in 1966, Equatorial Guinea in 1979, or Guinea-Bissau in 1998). Most of the recent coups have taken place in contexts where political violence (particularly in the form of long-running conflicts with jihadist insurgents) has been common. The non-violence of the coups thus stands in some contrast to the broader political context and may also relate to the level of popular support that some of these coups appear to have enjoyed. For example, some analysts have suggested that the coup in Mali in 2020 came as a relief to many people (82% according to Afrobarometer), who had lost faith in the leadership of President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta. Others have argued that the sanctions imposed after the 2021 coup in Mali actually increased support for the coup leaders. Similarly, the January 2022 coup in Burkina Faso (the fifth in a decade) which saw the ousting of President Roch Kabore, was also hailed by large and mostly youthful crowds as “what we want.”

Changing foreign connections

At the same time, while many coups throughout history have involved foreign involvement (real or alleged), the complex relationships between governments, coup leaders, and foreign mercenaries give the foreign element in recent coups a different significance. The growing involvement of the Russian mercenary organization Wagner in North and West Africa has been well documented. The realignment of countries such as Burkina Faso and Mali, shifting from France to Russia as a source of military support, is certainly significant at least for the prospects of a return to civilian rule. While France could be expected to exert some pressure for democratic governance, Russia has no such interests.

Near term outlook

None of this suggests that coups are becoming more acceptable. The African Union (AU) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) have both been firm in their responses to coups. International organizations have also condemned these anti-democratic interventions in the political system. For the first time in history, the AU had four countries simultaneously suspended for Unconstitutional Changes of Government (UCGs) and is currently reviewing its sanctions regime and enforcement mechanisms to deter UCGs. Furthermore, unlike before, the AU now has a more predictable post-coup transition pathway which often culminates in the conduct of democratic elections. However, the involvement of military leaders, in some cases (Mali, Chad, Burkina Faso etc.), as interim transition leaders, generates controversy regarding the AU/regional bodies’ firmly established “zero tolerance” policy for coup or military involvement in politics. While pragmatic, this type of transitional power can be seen to legitimize the actions of the coup leaders.

Overall, the changing nature of the coups that we have identified here also suggests that the demonstration effects of “successful” coups in the region may increase the likelihood of further coups in the near term, unless coups are seen and addressed as part of a much deeper systemic crisis - leadership and governance deficit- that continues to plague the continent. Without a holistic approach, democratic performance will likely continue to plummet, with varying manifestations, as it has for the past four consecutive years.