Explainer: Syria’s 2024 legislative elections

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

On 15 July, the Syrian regime of President Bashar al-Assad will hold elections for the Syrian parliament, the Syrian People’s Assembly (Majlis Al-Shaab). The elections to the 250-seat unicameral chamber, which are the fourth of their kind since 2011, will take place in only the roughly 70 per cent of Syrian territory under regime control. While the assembly is a rubber-stamp parliament that lacks the power to initiate legislation, and while the electoral dominance of the ruling Ba’ath Party is certain, the process is still a useful case study of how the Syrian regime operates.

In what context will elections take place?

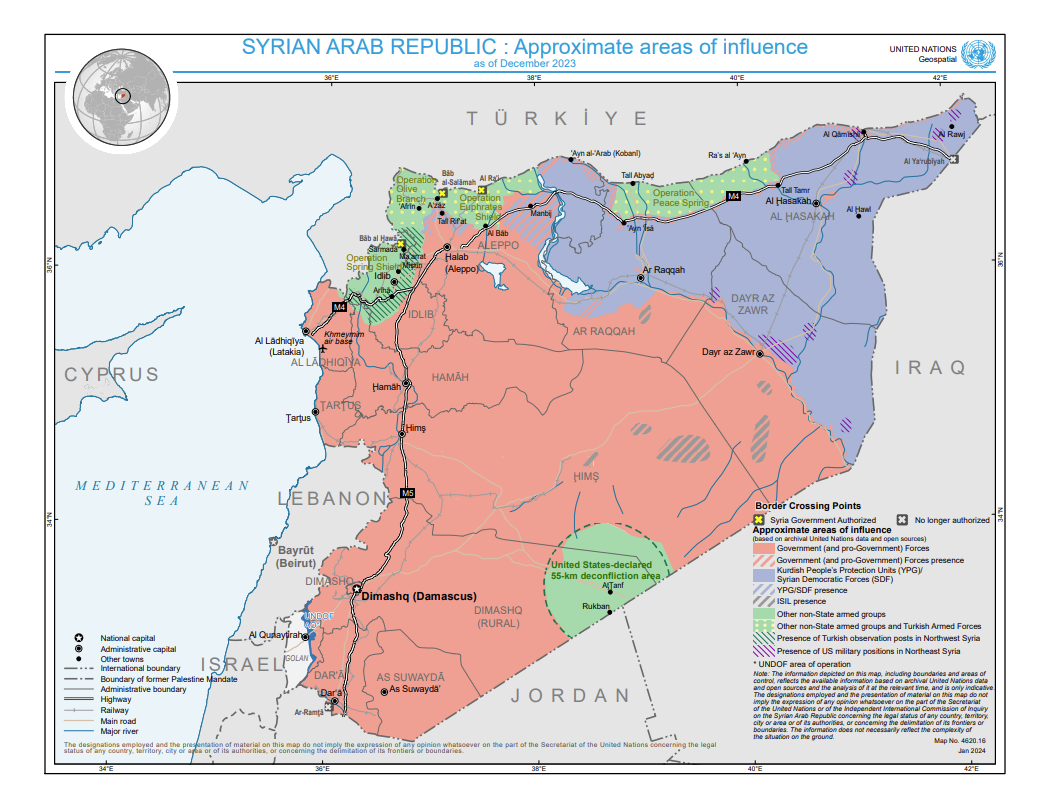

Syria remains deeply divided after more than 13 years of civil war, albeit a 2020 ceasefire in Idlib has reduced the intensity of fighting. The Assad regime, with the support of Russia, has retaken control of large parts of formerly rebel-held territories. However, significant areas of the north are still under the control of the opposition, the most prominent of which are the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in the northeast, the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA) along parts of the Turkish border, and the Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) in the northwest around Idlib.

Source: United Nations Geospatial (2024) (Click image to enlarge.)

Since the start of the war, the Assad regime has held parliamentary, presidential, and local elections at regular intervals. These processes, primarily managed by the regime's Higher Judicial Committee for Elections (HJCE) have been widely criticized for their lack of credibility. For example, in the 2021 Presidential election, Assad secured another term with more than 95 per cent of the vote although voter turnout hit record lows. Similarly, in the 2020 parliamentary elections, voter turnout decreased to 33 per cent compared to 57 cent in 2016. The Syrian government attributed this decline to the COVID-19 pandemic. Now, as Assad called for the upcoming 2024 parliamentary elections on 11 May, protests against the polls have emerged in Sweida, a Druze-majority region under regime control.

Meanwhile, opposition groups and their respective civilian administrative bodies are preparing separate electoral processes. The Kurdish SDF-connected Higher Electoral Commission of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria is preparing for municipal council elections, while in Idlib, the newly established HTS-linked Higher Elections Committee is planning for elections to the General Shura Council, the Islamist group’s civilian legislative body.

How do the elections work?

Despite the 2012 constitution's nominal end of the Ba’ath Party's monopoly and introduction of a multi-party system, power dynamics remain largely unchanged. According to Syrian opposition newspapers, there is an implicit understanding in the regime that around 183 parliamentary seats out of 250 are reserved for the National Progressive Front (NPF), a left-wing coalition which includes the Ba’ath Party and several smaller pro-government parties. Out of these, around 166 are reserved for the Ba’ath Party and 17 seats for the rest of the parties, whereas independents fill out the remaining 67 seats. Practically, this is carried out through the so-called block vote system. This plurality/majority system allows voters to cast as many votes as there are seats to be allocated in their electoral district. The electoral block with the most votes wins all the seats in the district. In theory, votes can be spread between different candidates. However, in Syria, voters chose between closed electoral lists, the most prominent of which being the Ba’ath-supervised National Unity lists of the NPF. While in some districts, such as Damascus, separate electoral lists for independent candidates are being formed, even independent candidates often run on the National Unity lists.

Source: Based on electoral results published by IPU. (Click image to enlarge.)

Candidate registration and approval process

Candidate registration is marked by stringent controls to ensure loyalty. Approximately 12,000 hopefuls registered to run for the 250 assembly seats during the seven-day registration period from 20 to 26 May, according to official sources. Among those, 9,194 were approved during the candidate selection process, vetted by both General Intelligence and the HJCE. This process is part of a historical pattern where both partisan and independent candidates face scrutiny to pass the filter of alignment with regime interests, limiting genuine opposition representation. High rates of candidate withdrawal –permitted up to seven days prior to Election Day– are frequent, meaning that not all those initially vetted will necessarily remain in the race until election day. Nevertheless, the true filters are the party nomination processes to decide which names go on the National Unity lists. A parliamentary seat is in this sense a way for the regime to reward its supporters and maintain patronage networks.

The workers and farmers quota

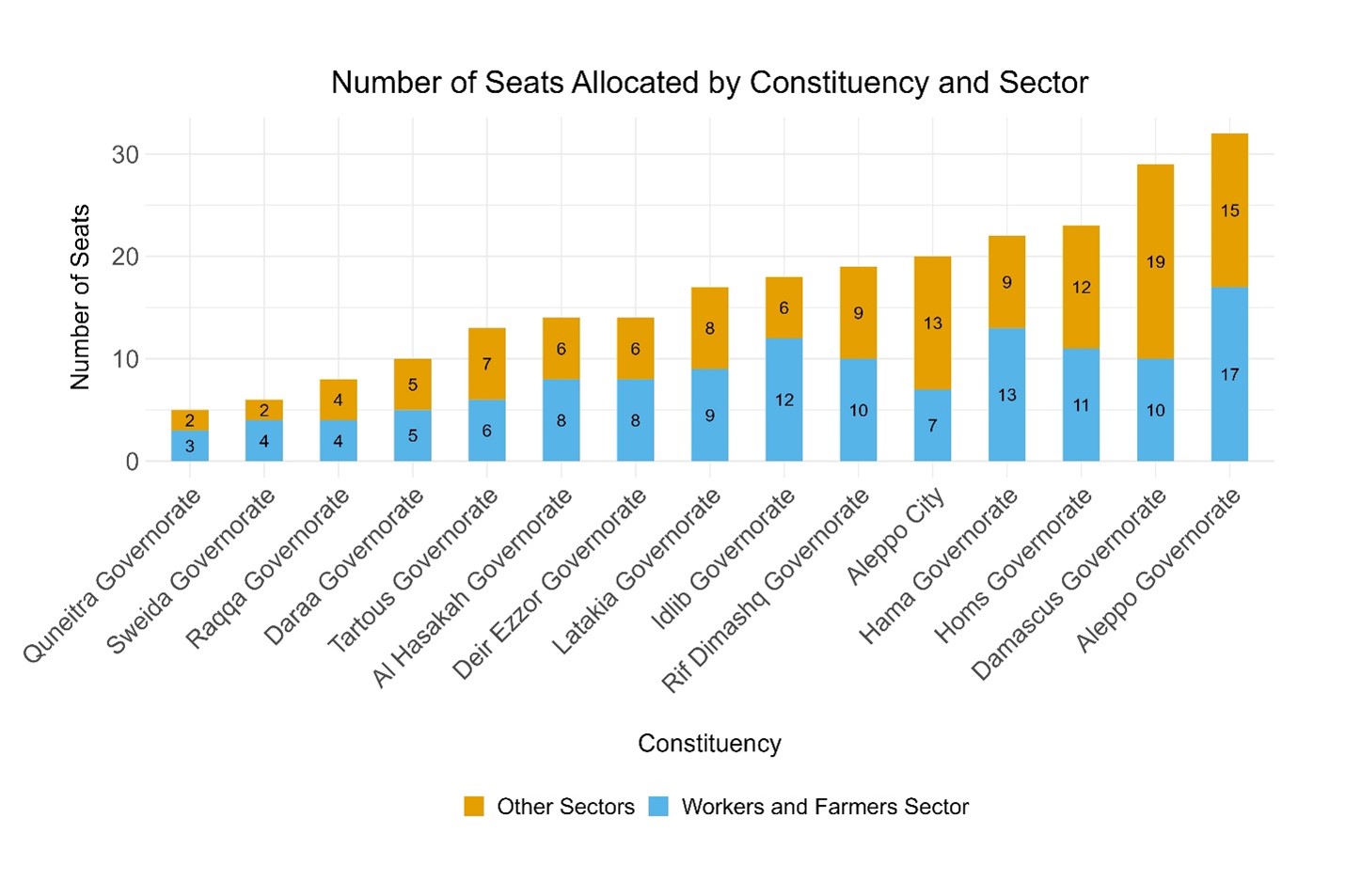

The 250-seat People's Assembly reserves 127 seats for workers and farmers, reflecting the Ba’ath Party’s historical socialist origins. However, the terms ‘worker’ and ‘farmer’ are poorly defined. According to the 2014 Electoral Law, candidates for these seats must not have companies registered under their names (except for agricultural production in the case of farmers). Despite this, some argue that these seats often go to regime allies with loose ties to the designated groups. In this election, 3,922 out of the 9,194 approved candidates are from the workers and farmers sector, also known as ‘Sector A’. The other candidates fall under the ‘Sector B’ category. There is no youth nor gender quota and women’s representation has historically been low. For example, in the 2020 election, women secured only 10.4 per cent of parliamentary seats. Just 6.9 per cent of seats were won by candidates aged 40 or younger.

The electoral districts

Syria's electoral districts are primarily based on the administrative division of its 14 governorates, except Aleppo Governorate, where Aleppo City is a separate constituency. The number of seats per electoral district, which is decided by presidential decree, does not correspond with population size. For example, the regime stronghold of Latakia has seven more seats allocated to it than Daraa, a region strongly associated with the opposition, even though the two governorates have roughly the same population size. This allocation has remained constant throughout all the four wartime parliamentary elections despite the demographic change produced by the war [1].

Source: Based on Article 2 of Decree No. (99), issued by President Al-Assad on 11 May 2024. (Click image to enlarge.)

What does this tell us about elections in Syria?

Deprived of both authority and genuine function, the People’s Assembly is effectively under the control of the executive. Syrians living abroad, including over 5 million refugees, some of whom are members of the opposition, are unable to run for office or exercise their right to vote from abroad without barriers. Consequently, the upcoming elections are limited in their ability to produce a roundly representative body of legislators. Despite their lacking credibility, the elections show first-hand the different ways that the regime seeks to consolidate authority and manage its support base. While the outcome of the elections is not bound to surprise anyone, the process surrounding them, and the eventual new faces they bring to the forefront, provide insight into the inner workings of the regime's support networks. Once elected, one of the most important tasks of the parliament will arguably be constitutional reforms, which are needed for Bashar Al-Assad to stay in power after 2028 [2].

[2] Article 88 of the 2012 Constitution limits the president's term in office to a maximum of two seven-year terms, applied non-retroactively. Under this provision, President Assad is eligible to remain in office until 2028. To amend this constitutional provision and potentially extend Assad's term, a proposal must be initiated by one-third of the People's Assembly. According to the procedure outlined in Article 150, this amendment must then be approved by at least three-fourths of the Assembly, in addition to receiving the President's endorsement.