Democracies and war: the Ukrainian and European responses

In the latest entry in the GSoD in Focus series, International IDEA argued that the Russian invasion of Ukraine has set in course a series of events that mark “a turning point in European history.” The immediate evidence for this is overwhelming: a historic refugee crisis, unprecedentedly swift sanctions, and the remilitarization of Europe’s largest economy. The invasion is indeed an attempt to remake the global order, but it also delivers a reminder of the intrinsic strengths and capabilities of democracies.

To judge from the increasingly elevated rhetoric of Russian President Vladimir Putin, the work of Kremlin-affiliated analysts to develop a post-hoc strategic justification for the invasion, and a since-deleted piece celebrating a swift Russian victory, the Kremlin envisioned the invasion as a bold stroke that would mark the end of Western geopolitical dominance, and help bring about a new, multipolar, and post-liberal international system. The decline of American unipolarity had opened a space for Russia to behave, once again, as an empire. Russia would act, create new realities, and leave weakened democracies to simply study what it has done. Putin’s drastic underestimation of both Ukrainian resistance and western resolve has, for the moment, scuttled these plans.

But the aim of this blog is not to analyse one man’s motivations. The above should not be taken as definitive, but as a prominent narrative that the Russian state, which has often been ideologically eclectic, may return to in the future when circumstances demand. Authoritarians are not free from domestic pressures, and those drivers, as well as the nature of popular support and protest, are the subject of fierce debate. What is more interesting is the rapid transformation of Ukraine’s political geography and its echoes across the continent.

Ukrainians have organized mass demonstrations in the face of Russian military occupation in Kherson, Melitopol, and Kharkiv, and videos of unarmed civilians physically confronting Russian troops are commonplace. Defying pre-war understandings of Ukraine’s political cleavages, many of these cities largely sat out the 2014 protests, or previously routinely supported political parties that advocated for an accommodationist resolution to resolving Ukrainian and Russian tensions. The breadth and strength of Ukrainian resistance is a vital reminder of the mobilizing power of democracies under threat.

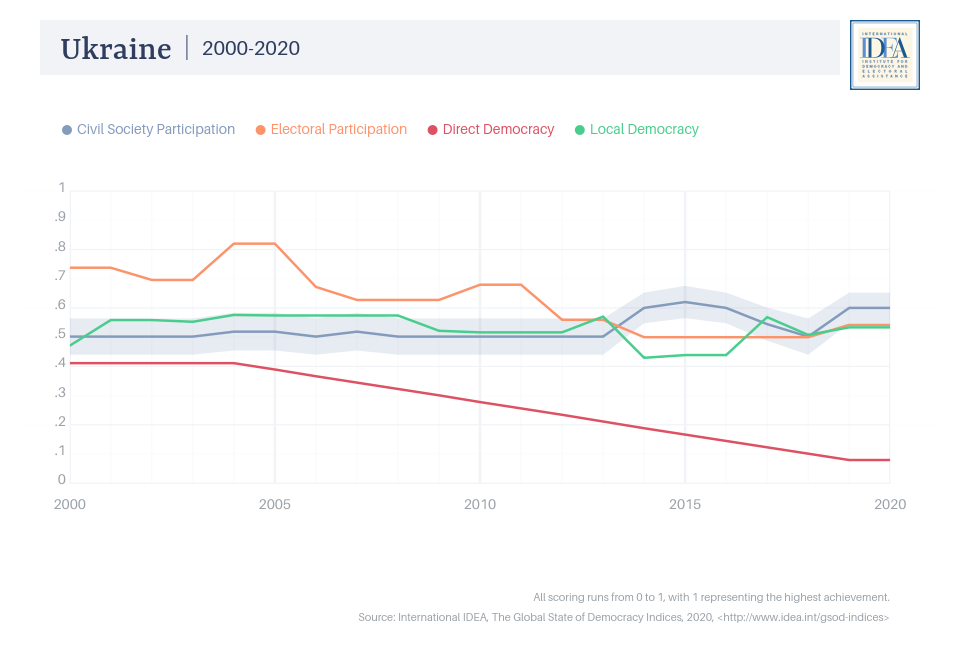

The roots of this mobilization can be observed in a post-2014 rise in the participation in civil society organizations, which has not followed the trend of decreasing or inconsistent participation in formal electoral processes:

Given this demonstration of the resilience of a democracy roused in anger, it is worth dwelling on the paper’s warning that European democracies should pay close attention to how Kremlin-friendly right-wing populists react; it is difficult to envision the Russia-led “right internationale” surviving its hegemon’s sudden shift to imperial revanchism. Russia did not prepare international audiences for its invasion with a propaganda campaign comparable to the one which preceded the 2014 annexation of Crimea, leaving its international allies without a consistent, defensible narrative for their local constituencies. Accordingly, far-right (and left) parties in Europe that have publicly embraced Putin will have to account for their past support in the coming elections.

One well-worn path, at least for the far-right, would be to resort to demagoguery: anti-Russian sentiment may prove to be fleeting, but it could serve as a springboard for politicized discussions on which populations are and are not “European.” However, as tempting as the thought may be, the risk of mass democratic enthusiasm leading to undesirable ends is not limited to one extreme of the political spectrum. More sober-minded politicians may channel popular support for Ukraine into increasingly tough sanctions, which despite their non-violent reputation, can cause serious unintended harm to ordinary Russians or the countries in its “near abroad”, or a rash response by the Russian state itself.

International IDEA’s The Ukraine Crisis and the Struggle to Defend Democracy in Europe and Beyond is available here.

This blog reflects the personal opinions of the author and does not represent the official position of International IDEA.