Chile’s constitutional referendum: Will the participatory process end in rejection?

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the institutional position of International IDEA, its Board of Advisers or its Council of Member States.

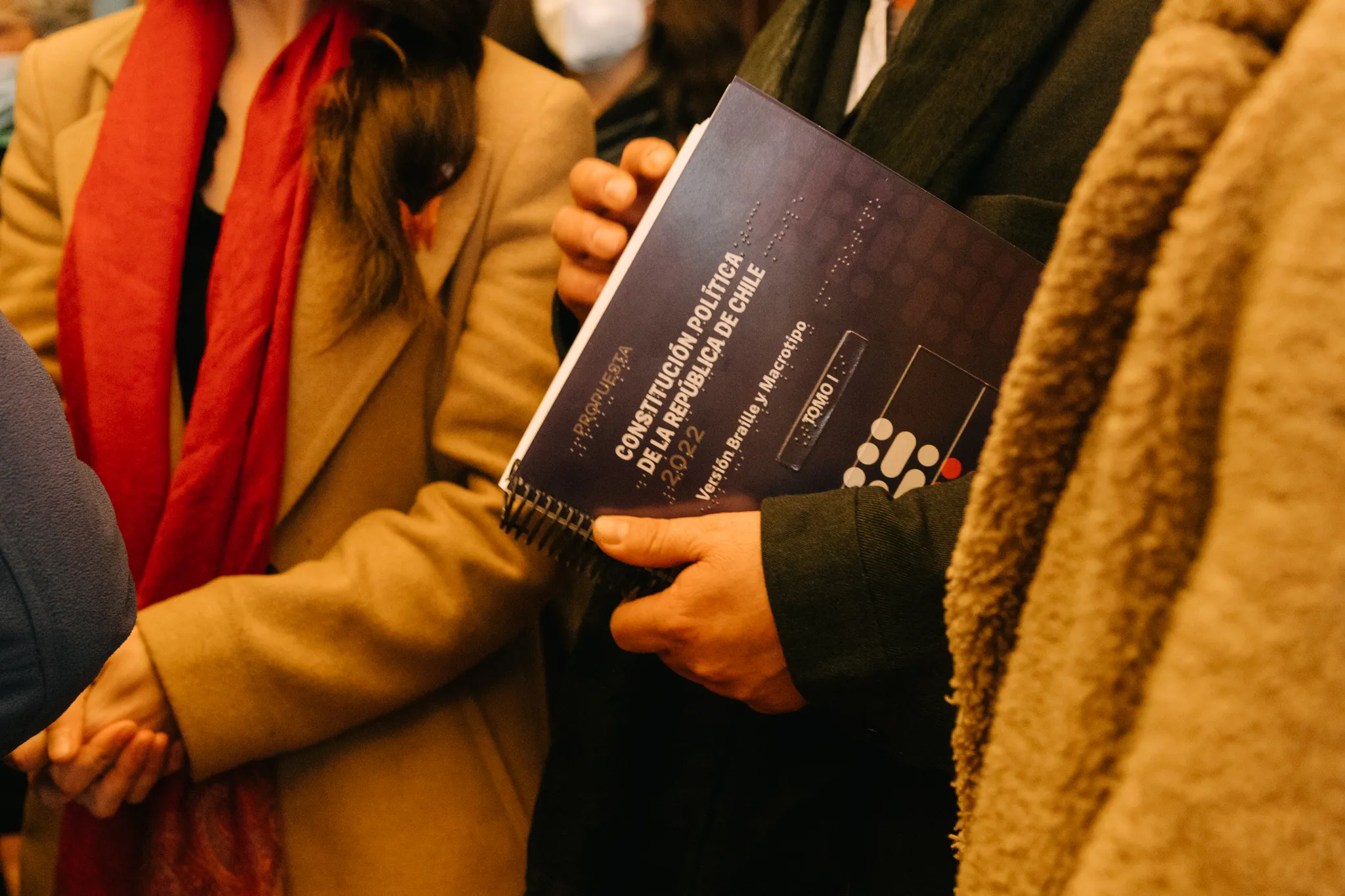

Constitutional reform in Chile has been in the works for at least nine years and is now approaching a critical moment. The current process grew out of a protest movement (Estallido Social) in 2019. The demand for constitutional change was then given concrete support in a referendum in 2020, where the vast majority of those who voted supported drafting a new constitution. The resulting process, led by a popularly elected and commendably diverse group of drafters, has now come to a close. Surprisingly, though, despite widespread popular participation in the process, polls indicate that the draft is likely to be rejected in the referendum scheduled for 4 September. (However, it should be noted that since voting in the referendum is compulsory, prediction on the basis of the polls is difficult.) In a comparative context, a rejection of the draft would be a remarkably rare event.

My study with Zach Elkins, which analyzed 644 referendums between 1789 and 2016, found that referendums to ratify new constitutions passed 94% of the time – often with very high levels of support. Over the last half century in particular, ratification via referendum has become increasingly popular. At the same time, so few constitutions have been rejected by voters that it perhaps appears to be an almost costless choice for politicians to submit their work to a referendum.

The likely outcome on 4 September would place Chile in very rare company indeed.

Despite overwhelming support for initiating a constitution-making process and broad participation in the drafting process itself, there are doubts about the outcome. Sensationalized media coverage of the more radical proposals suggested at early stages may have undercut public trust in the drafters and the text. Now, at an elite political and legal level, a number of criticisms have been made regarding the content of the proposed constitution, including the potential weakening or fragmentation of the party system and the way that the new balance of powers could lead to gridlock. Notwithstanding its phenomenal length, the text also leaves many matters to be decided by ordinary legislation at some point in the future. Among the general public, those who say they will vote against ratification highlight healthcare, education, pensions, and the plurinationality of the state among their top concerns.

In an international-comparative context, a rejection of the draft constitution in Chile would be a very rare event. In the Chilean context, one might wonder if the failure of two successive attempts at constitutional change would dampen enthusiasm for yet another constituent process. Even so, the President has argued that if this process fails, a new one should start right away. Surprisingly – given that the constitution-making process has been ongoing for the better part of nine years already, this position is supported by 35% of Chileans. The level of support for change manifested in 2019 and 2020 apparently remains high. If Chile can push forward into a successful third attempt at reform, it would be almost as remarkable as a rejection in the referendum, and could provide some insight for would-be constitutional reformers in other countries.

Chile’s constitutional moment may last much longer than anyone expected.